Abstract

Keywords: Public policiespublic healthmanagementinstitution buildingnew institutionalismmedia monitoring

Introduction

The countenance of public discourse in shaping public healthcare policy-making can hardly be engaging without the dimension of media reflecting the drivers, challenges and setbacks of reform, changes and current practices in the field. The literature on healthcare policy convergence as policy transfer, and more specifically healthcare policy transfer and feedback has benefitted widely from approaches that summed up local policy responses from both central level and local communities elites (both politicians and health professionals) within bottom-up comparative reviews (Clavier, 2010).

Background of healthcare policy-making

Healthcare policies as political or electoral theme capable of issuing lively debates and major mobilization and support has also been identified in the literature (Vasev & Vrangbæk, 2014, p. 693). This has revealed itself as a relevant theme of impulse, need and urgency for healthcare reform and political debates in media coverage. Public dissatisfaction in governmental policies in general and public healthcare services in particular were also assessed in analyses that expose the public’s “alternative” expression of implementing policies viewed as a means of enhancing citizens’ engagement into policy-making either through private financing or other forms of cooperation, inducing the retirement from the welfare state (Cohen and Mizrahi, 2012).

Comparative welfare state research has highlighted that globalization itself is a triggering factor for healthcare spending in different degrees according to the specificities induced at the level of each welfare state (Fervers, Oser & Picot, 2016). At the same time, empirical analyses have suggested that public expenditures in healthcare are directly correlated to the values of health indicators (Akhmedjonov, Güç & Akinci, 2011). Moreover, by exploring the core of national European health policies against a specific World Health Organization (WHO) policy framework it has been argued that violence and injury prevention stand at the basis of national initiatives (Parekh, Mitis & Sethi, 2015).

Within the wider European Union (EU) governance framework, health policy dynamics appears in-between national healthcare policy mechanisms and EU specific regulatory competence envisaged in subsidiarity principle according to EU Treaties (Permanand & Mossialos, 2005). Thus the outcomes of EU specific developing health laws on national policy responses (public or private health institutions and actors) seems to trigger consistent debates and seminal understandings about compliance (Greer & Rauscher, 2011). For instance, what might commence at EU level as an awareness-raising initiative seldom has to rest at national level in order to be futilely translated into strategic guideline and/or policy option (Felton & Hall, 2015). It takes a civic engagement (Olimid, 2015) corroborated to a consumerist/market-oriented equation to figure how to transform national healthcare systems to fit the needs of patients (healthcare services consumers) in terms of institutional design and policy-making throughout the EU Member States (Ardley, Mcmanus & Floyd, 2013). This approach has been stretched so as to encompass even the design facets of quality conditionality standards for national health establishments observed in tight correlation of “policy, strategy and organization” (Mills et al., 2015) or in diverse critically comparative analytical approaches (Kennedy, 2015; Whitehead, 1999).

Although difficult to attain, the establishment of a European healthcare union under the dynamics of national-supranational relations and bottom-up vs top-down pressures was regarded as beneficial in the sense of empowering citizenship and increasing the feeling of “togetherness” (Vollaard, Van de Bovenkamp & Martinsen, 2016). The quality of the national retirement schemes and healthcare policies has acquired the status of substantive explanatory variable for migration fluxes analysed within the EU governance legislative framework. European citizens’ entitlements to access public healthcare are dealt with in comparative analyses assessing workers’ rights as against retired or other categories of beneficiaries in certain European regions (i.e. Southern Europe and Northern Europe) (Dwyer, 2001).

Inquiring on the possibility to identify a common denominator for a European healthcare model by examining citizens’ satisfaction towards national public health services and other vectors (including, but not limited to organization of national health service and ties to the old regime, financial contributions, the share of the private health services field, customers’ privileges etc.) analyses unraveled peculiar demarcations between Northern and Southern European states that could attach a trademark to national health systems (Toth, 2010).

Customizing Central and Eastern European (CEE) national systems

As South European states have strived to address the severe economic and financial issues through austerity measures for a serious period of time making conjectural and even opportune the state’s stepping down from the welfare sector there is a clear trend towards health institutional and policy reform throughout Europe (Petmesidou, Pavolini & Guillén, 2014).

Considering this aspect, the institutional design of healthcare services for Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries becomes even more challenging due to their suspension on certain dimensions: (1) the logistical factor (including budgetary constraints and cost-effectiveness relative importance for decision-making), (2) organizational culture (values, norms, rules, image, communication, including relation to political factor and government (in)stability) and (3) organizational structure (including national health system) (Ferrario et al., 2014; Polese et al., 2014). Policy transfer seems to provide the key solution to the problem of adapting CEE national health systems to ever growing services pretences. Since public health systems cannot meet citizens’ needs the literature has turned to the private operators or even to public-private partnerships (PPPs) to absorb the cumulative demand. Investigating CEE national health systems’ capacity to assume PPP schemes, some studies have revealed that exporting PPPs can be imposed in the area; however, the actual implementation of some policies is lacking or is poorly managed in the public field (Holden, 2009).

The notion of governing medical performance acquires a key position in health policy-making approaches no matter the dominant organisation ideology in-between centrality and de-centralised units (Kuhlmann & Burau, 2008). The state’s central role in policy-making in CEEC health systems as against other (private) additional actors explains much of the differences in relation to Western countries health systems’ performance (Kaminska, 2013). Analyses have shown that the scarcity of resources alleviates CEEC central authorities’ reserves in adopting strategic measures that would co-interest private health-providers by boosting the impact and competence of international actors. An example in this sense is the Cross-Border Patients’ Rights Directive and the states’ different reactions and responses as regards their national transposition strategies and policy-implementation (Vasev, & Vrangbæk, 2014)..

Problem Statement

Starting from the assumption that managing institutional design of healthcare services is dependent on three variables: (1) the logistical factor (including budgetary constraints), (2) organizational culture (values, norms, rules, image, communication) and (3) organizational structure, the paper deploys a content analysis of different news sources in order to identify the manner in which health is correlated to certain economic, social, political, juridical aspects during a certain period of time. Consequently the paper discusses the results of a media analysis aimed at identifying the general themes, trends and patterns in the media coverage of the institutional design of healthcare services and portrayal of the systemic changes and challenges in the field. The analysis is thus centered on finding evidence of media bias towards certain issues in the management of institutional design of healthcare services and as regards the policies of public health. The analysis is founded on measuring both the quantity and quality of media coverage of healthcare services issues, on accomplishing extended interpretations of the coverage within the overall discussion of institutional design/institution building and public policy-making/policy-implementation in the light of content analysis methodology.

Research Questions

In this sense and considering the methodological rigour of an analytical study, the research was inquisitive in finding the appropriate answer to a set of guiding questions: how is healthcare covered in the national mainstream media? What was the frequency associated to healthcare-related news appearance in the media? What are the major themes/major issues covered by the media as regards health? How is authorities’ action in the field reported by the media? Is there a biased discourse as regards healthcare or as regards some issues associated to it (policy-making, organization, crisis situation and response etc.)? How is citizens’ perception affected by media rhetoric on healthcare? Consequently, considering the research temporal dimension (1 May 2016-30 June 2016) another research question could be driven from this rationale, whether we can trace records of an intensification in health-related articles frequency during the first half of the analyzed period, roughly corresponding to May 2016? If so, could this indicate the correlation of healthcare (as social policies) as an election campaign theme?

Purpose of the Study

The study is targeted on profiling the manner in which different topics associated to health are covered in the national mainstream media, identifying the frequency and distribution of articles, identifying the most relevant and impact themes and identifying traces of bias in relation to authorities’ action, healthcare institutions, also to healthcare system in general and social policies in particular. In this sense we have to nuance the research and state that the selection of the monitoring period (1 May-30 June 2016) was not random, but considered the first month of research (May 2016) for its electoral campaign context, while the second month (June 2016) as the aftermath of local elections (the local elections for mayor, local and county councils were organized on June 5th, 2016). Coupled with this rationale, we had to ask ourselves whether we could find evidence on the intensification of health-related issues coverage during the first month of the monitoring period. In this sense, the analysis was firstly directed towards identifying frequencies in the distribution of articles along the studied period and among the specific news sources. Secondly, the analysis was targeted along identifying the key themes in the selected articles that would signal the correlation of healthcare with elections period. Thirdly, the news framing analysis was employed in order to identify the strings attached to the selected articles;

Research Methods

The research used media content analysis as research methodology. The paper thus discusses the results of a media analysis aimed at identifying the general themes, trends and patterns in the media coverage of the institutional design of healthcare services and portrayal of the systemic changes and challenges in the field. The analysis is thus centered on finding evidence of media bias towards certain issues in the management of institutional design of healthcare services and refering to the policies of public health.

Content analysis

Research methodology concentrated on correctly, objectively and comprehensively identifying all the relevant material focusing on healthcare specific issues implying the search along healthcare keywords. The research aimed at analyzing the manner in which national media relates to healthcare policies, thus the interest became focal on coverage featuring authorities’ healthcare concerns, challenges, actions and programs, acts of speech, statistics and informative numbers, systemic fallacies and individual cases of breach, national health-related crises. The analysis followed the monitoring of electronic editions of one national journal (Jurnalul Național) and two online news sources (HotNews.ro and DC News) during 1 May 2016 – 30 June 2016 specifically addressing Romanian healthcare policies and Romanian healthcare crisis. The period proved to be a suitable choice since a total number of 406 articles (n=406) were selected and thoroughly analyzed.

Quantitative and qualitative dimensions of analysis

The analysis was founded on measuring both the quantity and quality of media coverage of healthcare services issues, extended interpretations of the coverage within the overall discussion of institutional design/institution building and public policy-making and/or policy-implementation.

Findings

The media articles content analysis implies both the quantitative and qualitative dimensions of study. To give an illustration, the quantitative condition was followed through the frequency analysis and articles distribution along the selected time period. By contrast, the qualitative dimension was accomplished through the thematic analysis of both headlines and content and the news framing analysis. The analysis is directed towards challenging the idea of healthcare coverage intensification during electoral campaign context. In this line of thought and guided by the research questions outlined above, the analysis seeks to highlight whether there is evidence in support for this assumption, by analysing elements of article distribution and frequency, thematic presence and framing into specific media formats.

Distribution of selected articles

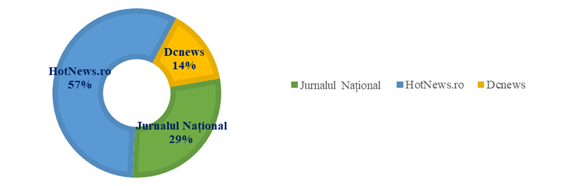

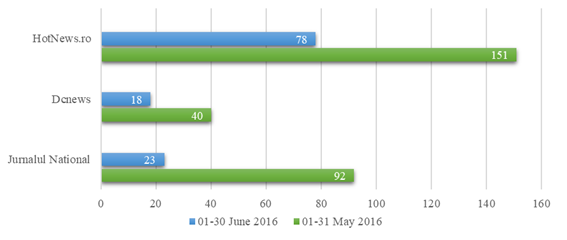

In response to the first two research questions risen in the initiatory methodological part of this study, the distribution of selected articles from online news sources during period under analysis presents the following situation (Figure

The analysis of the distribution of articles per journal/online news source per month shows a peculiar situation: the most compelling reason to test healthcare as a major campaign theme stands in the media coverage associated to health specific issue during the analysed period. The monthly distribution of articles per journal or online news source shows evidence for the boost of healthcare as a political theme, with a propensity for political discourse weight on severe issues and a redundancy of articles during campaign period (Figure

Thematic analysis – healthcare as electoral campaign theme

The headlines analysis undergone for the selected period 01 May-30 June 2016 shows a distribution of titles along the following lines (1) existing healthcare legislative frame, (2) state of healthcare infrastructure and (3) incidents and tragic events linked to the functioning of healthcare system (of which one could mention the aftermath of the November 2015 Colectiv club tragedy; the diluted disinfectants crisis; the hospitalized nosocomial infections; the babies’ with uremic hemolytic syndrome crisis; the national vaccines crisis; the football player’s intensely mediatized death uncovering fallacies of private ambulance system and hospitals’ deficits; the overcrowding phenomenon in hospitals; the poor hygiene in hospital units; the lack of hospitals targeted for children; the problems facing cancer and hepatitis C patients; the healthcare personnel wages and public field wages policy-drafting; the lack of qualified personnel and the associated brain drain phenomenon; and the physicians’ deficit especially for the rural areas.

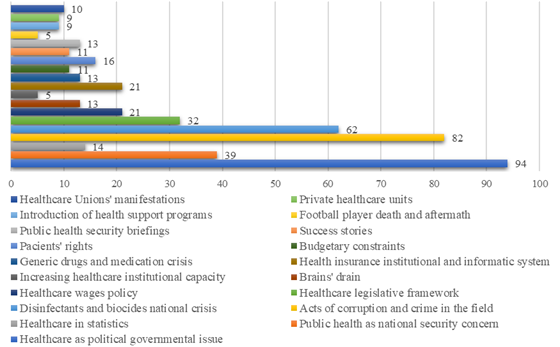

The thematic analysis rendered in Figure

Firstly, it becomes obvious that healthcare entered the dimension of intra-governmental relations, power-opposition relations included, either as they dealt with governmental re-adjustments, government reshuffle, wage legislation drafting and adoption, political declarations and statements within diverse crisis situations (i.e. drugs and vaccines crises, biocides and disinfectants crisis, wages policy, other health security threats and/or other publicized health-related incidents). Furthermore, we must not neglect the dimension of the media coverage for healthcare reaching the status of national priority and concern on the agenda of the Chief of State-presided State’s Defence Supreme Council (CSAT) and in the Romanian Information Service (SRI) current activity.

Secondly, either detractive, defamatory or allegations by politically affiliated public persons made during campaign soon triggered media attention which proved not to be immune to portraying such statements.

Thirdly, the coverage of healthcare wages policy-making coupled with the education-healthcare salary policies comparisons and union activity during the analysed period. Notably important proved to be the coverage of healthcare human resources deficiencies associated to the brain-drain phenomenon and budgetary constraints and the introduction of health support programs and assistance.

Fourthly, the media covered other popular themes with major impact upon intensive health services consumers: health statistics, patients’ rights, public-private healthcare systems comparisons, benefits and costs associated to healthcare legal framework changes and/or reforms, medication and vaccines crises, public and private health systems loopholes and malfeasances, health insurance system (including health card informatics system blockages or the Health Insurance National Chamber (CNAS) challenges).

Likewise, this type of discourse on health-related issues kept the headlines of the selected online news sources along with the intense mediatisation of the acts of corruption, misdemeanour, malpractice or abuse from within the healthcare system. 82 articles included in the analysis featured the acts of corruption, wrongdoing or breach of either medical personnel or public-private partnerships. The diluted disinfectants and biocides national crisis headlined 62 articles, while 13 articles had as main theme the generic drugs and medication crisis, including nosocomial infections in public hospitals and illegal human drugs testing in public clinics.

News framing analysis

As regards the news framing, either “issue-specific” or “generic”, the analysis is established on Claes H. De Vreese’s approach (2005). According to this admission we identified five media frames in the selected articles: “human impact” frame, “powerlessness” frame, “economics” frame, “moral value” frame and “conflict” frame.

Firstly, the “human impact” frame was identified in articles nested on individuals’ or categories’ extreme or intensively sensitive situations (De Vreese, 2005, p. 56). The analysis identified this framing in articles pinned to civil touching stories, controversial situations and unprecedented cases capable of stirring strong popular discontent on a specific matter, personal dramas etc. Such were the following cases depicted during 01 May-30 June 2016: “Un mare chirurg părăsește România, după ultimele scandaluri din Sănătate” [Great surgeon leaves Romania following latest healthcare scandals] (Jurnalul Național, 26 May 2016); “Cum funcționează sistemul care pune doctorii pe fugă” [How does the system putting doctors on the run function] (Jurnalul Național, 26 May 2016); „Caz fără precedent în sistemul medical românesc. Reacții controversate stârnite de condițiile cerute de o gravidă la naștere” [Unprecedented case in Romanian medical system. Pregnant woman in labor stirs controversial reactions] (HotNews.ro, 23 June 2016); “Replica dură a unui doctor gălățean, după ce o gravidă a pus o serie de condiții la naștere: Mofturi de prințesă, poți naște stând în cap” [Harsh reply of Galați doctor after pregnant woman conditions birth: Princess’ trifles, one can give birth standing upside down] (HotNews.ro, 22 June 2016); “Drama unui tânăr rănit în Colectiv” [Colectiv-wounded young male’s drama] (HotNews.ro, 19 May 2016); “Gestul făcut de noul ministru al Sănătății: Dacă întâmpinați probleme...” [Gesture made by new Healthcare minister: Should you encounter problems…] (DCNews, 22 June 2016).

Secondly, the “powerlessness” frame was depicted in articles aimed at highlighting the theme of compulsion crushing defenseless individuals or different categories (De Vreese, 2005, p. 56). It was particularly present in articles decrying the state of Romanian healthcare system, the (non-)observance of patients’ rights, the dependence on some drives etc.: “De ce trăim mai puţin decât ceilalţi europeni. Pacienţii dau statul în judecată” [Why do we leave less than other Europeans. Patients sue the state” (Jurnalul Național, 28 June 2016); “România, locul 1 la numărul de morți cu zile” [Romania, first place in number of inexcusable deaths] (Jurnalul Național, 25 June 2016); “Interferon-free: sute de mii bolnavi, 3.000 tratați [Interferon-free: hundreds of thousands ill, 3000 treated] (Jurnalul Național, 22 June 2016); “Muribunzii României, trataţi din mila străinilor” [Romania’s dying, treated out of strangers’ mercy] (Jurnalul Național, 24 May 2016); “Cum plătesc românii serviciile medicale gratuite dacă merg în privat” [How do Romanians pay for free medical services when opting for private] (Jurnalul Național, 17 May 2016); “Baronii spitalelor au oroare de medicii români formați în Occident” [Hospitals’ well-offs loathe Romanian doctors trained in the West] (Jurnalul Național, 13 May 2016); “Sănătatea, bolnavul cu metastaze pe care l-au “oblojit” 26 de miniştri” [Healthcare, the metastases patient “treated” by 26 ministers] (Jurnalul Național, 10 May 2016); “Proiectul noii legi a sănătăţii, din 2008, a fost îngropat de mafia din acest sector” [New healthcare bill drafted in 2008, buried by sector mafia] (Jurnalul Național, 07 May 2016); “Spitalul cu peste 50 de infecţii nosocomiale în ultimul an” [The Hospital with over 50 nosocomial infections last year] (DCNews, 26 May 2016); “Plata pentru tratamentul răniților de la Colectiv, refuzată” [Refused payment for treatment of Colectiv-injured] (DCNews, 25 May 2016).

Thirdly, the articles framed on “economics” frame are pre-printed on the economic outputs or outcome of the governmental measures, either at national level or as individual and/or community sequels and/or costs of policy-making (De Vreese, 2005, p. 56). “Economically”-framed articles in our analysis triggered special media and public analysis on government ordinances effects for population or specific professional categories, wage pressures on state budget and the upshots of budgetary deficits, statistical previews, individual grinding of specific legislative enactment: “Ordonanţă bună, dar cu efect întârziat” [Suitable Ordinance, late effect] (Jurnalul Național, 07 June 2016); “Presiunea salarială a slăbit” [Salary pressure weakened] (Jurnalul Național, 07 June 2016); “Împrejurările permit decapitarea oncologiei” [Circumstances allow oncology beheading] (Jurnalul Național, 02 June 2016); “Codul Fiscal, modificat. Cât plătești spitalizarea dacă nu ai asigurare” [Modified Fiscal Code. How much does one pay for hospitalization with no insurance] (DCNews, 31 May 2016); “Cifre teribile pentru România. Viitorul negru al sistemului de sănătate” [Terrible numbers for Romania. The dark future of healthcare system] (DCNews, 21 June 2016); “Noua lege a salarizării. Cine câștigă mai mult” [New wage law. Who earns the most] (DCNews, 17 May 2016); “Activitatea Secției Pediatrie din Spitalul Județean de Urgență, suspendată după ce singurul medic specialist a plecat în concediu de odihnă” [Emergency County Hospital Pediatry Section activity suspended following only specialist doctor leaving in vacation] (HotNews.ro, 30 June 2016); “Românii riscă să rămână fără servicii medicale gratuite de la 1 iulie” [Romanians risk losing free medical services starting July 1st] (HotNews.ro, 21 June 2016).

Fourthly, “moral values” framed articles inkling the infringement and/or encroachment of health system or societal ethics, deontology, behavioural norms (De Vreese, 2005, p. 56). Articles specifically made reference to bribes, systemic or professionals’ corruption: “Mita în domeniul sănătății, mai mare decât în altele” [Healthcare bribe, bigger than in other fields] (Jurnalul Național, 09 june 2016); “Arestul struţilor” [Ostrich’s arrest] (Jurnalul Național, 03 june 2016); “Minima reparaţie morală” [Minimum moral repairs] (Jurnalul Național, 25 May 2016); “Scumpi și prețuiți Baroni” [Dear and valued Well-offs] (Jurnalul Național, 09 May 2016); “Cum se întâlnește dreptatea cu interesele nelegitime” [How does justice meet illegitimate interests] (Jurnalul Național, 10 May 2016).

Finally, by “conflict” framing articles (De Vreese, 2005, p. 56), the media coverage highlighted the government’s anti-corruption commitments, power-opposition political allegations about systemic corruption, news coverage about national health crises: “Situaţia medicamentelor, o catastrofă” [Drugs’ issue, a catastrophe] (Jurnalul Național, 23 June 2016); “Sistemul sanitar este unul feudal” [Healthcare system is a feudal system] (Jurnalul Național, 23 June 2016); “Controlul dezinfectanţilor, după limitele bugetare” [Disinfectants’ control, following budgetary limits] (Jurnalul Național, 15 June 2016); “Dosarul cobailor umani” [Human Guinea Pigs file] (Jurnalul Național, 01 June 2016); “Toată lumea vorbește de spitale, dar nimeni nu face nimic” [Everybody talks about hospitals, nobody does anything] (Jurnalul Național, 26 May 2016); “În cazul Hexi Pharma e nevoie de crearea unei celule de criză, nu de grup de lucru” [Crisis cell required in Hexi Pharma case, not working group] (Jurnalul Național, 25 May 2016); “A venit vremea ca medicii să nu mai stea pe margine aşteptând doar ca alţii să facă ceva” [Time has come for doctors not sitting on the side waiting for other to do something] (Jurnalul Național, 23 May 2016); “Nu vom rezolva corupţia în sănătate doar arestând şi trimiţând oameni în judecată; e nevoie şi de alte măsuri” [We cannot solve health corruption just by arresting and suing people; one needs other measures] (Jurnalul Național, 23 May 2016); “Situația este atât de gravă în sănătate, încât se impunea constituirea unei celule de criză” [Situation so severe in health that required crisis cell establishment] (Jurnalul Național, 21 May 2016); “Patronii de la Ambulanţa Puls, resuscitaţi cu banii statului” [Owners of Puls Ambulance, resuscitated with state money] (Jurnalul Național, 20 May 2016); “Șase luni grele” [Six harsh months] (Jurnalul Național, 20 May 2016); “Medicii respiră. Restul bugetarilor, furioşi” [Doctors breathe freely. Rest of budgetary employees, angry] (Jurnalul Național, 19 May 2016); “Problema infecţiilor nosocomiale, cunoscută de Minister de 10 ani” [Nosocomial infections issue known in Ministry for 10 years] (Jurnalul Național, 19 May 2016); “Ordonanţa salarizării, axată pe Sănătate” [Wage ordinance, centred on health] (Jurnalul Național, 18 May 2016); “Găurile negre” [The black holes] (Jurnalul Național, 06 May 2016); “Medicii de familie, scandal uriaș cu CNAS: ‘Manipulează publicul’“ [Physicians in huge scandal with Health Insurance National Chamber (CNAS): “It manipulates the public”] (DCNews, 27 June 2016); “Medicii de familie declanșează protestele: ‘Este picătura care a umplut paharul’” [Physicians start protests: ‘It’s the straw that broke the camel’s back’] (DCNews, 16 June 2016); “Situație revoltătoare în sănătate: Cum ne păcălesc clinicile private” [Outrageous situation in health: How do private clinics fool us] (DCNews, 08 June 2016); “Un nou scandal de proporții în sănătate. Este nevoie de o decizie politică” [New huge healthcare scandal. Political decisions needed] (DCNews, 30 May 2016); “Colegiul Medicilor, supărat pe declarațiile ministrului Sănătății privind organizarea feudală a sistemului: Personalul din

Conclusion

In light of the evidence provided through the media monitoring of the selected online news articles we have a more conclusive understanding of the press coverage of healthcare policy-making and policy implementation. Needless to say that the 2016 local elections political context fuelled the debates and spiralled the health theme on top of the political agenda. There were many arguments in leading to this conclusion which stem from frequency in the media coverage, the disproportionate distribution of health-related articles during the campaign period (May 2016) in relation to the subsequent month under scrutiny, the thematic analysis and the weight of certain themes related to the healthcare field during campaign period (i.e. political allegations, corruption and malfeasance, challenging the authorities, public health and healthcare as national security concerns, healthcare wages policy, healthcare unions activity etc.) and framing analysis deployed in order to uncover the specific formats used in media practices to encase the news.

References

- Akhmedjonov, A., Güç, Y. & Akinci, F. (2011). Healthcare Financing: How Does Turkey Compare?, Hospital Topics, 89(3), 59-68. doi:

- Ardley, B., Mcmanus, J. & Floyd, D. (2013). Does Europe still represent a healthy deal in times of increased global challenges and reduced levels of growth? A market, service and social perspective of European healthcare. Public Money & Management, 33(6), 421-428. doi:

- Clavier C. (2010). Bottom–Up Policy Convergence: A Sociology of the Reception of Policy Transfer in Public Health Policies in Europe. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 12(5), 451-466. doi: DOI:

- Cohen, N. & Mizrahi, S. (2012). Comparative Implications: Public Policy and Alternative Politics in the Case of the Israeli Healthcare System. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 14(1), 26-44. doi:

- De Vreese, C. H. (2005). News framing: Theory and typology. Information Design Journal + Document Design, 13(1), 51–62.

- Dwyer P. (2001). Retired EU migrants, healthcare rights and European social citizenship. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 23(3), 311-327. doi: DOI:

- Felton, A.-M. & Hall, M. (2015). Diabetes in Europe policy puzzle: the state we are in. International Diabetes Nursing, 12(1), 3-7. doi:

- Ferrario A., Baltezarević D., Novakovic T., Parker M. & Samardzic J. (2014). Evidence-based decision making in healthcare in Central Eastern Europe. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 14(5), 611-615. doi:

- Fervers, L., Oser, P. & Picot, G. (2016). Globalization and healthcare policy: a constraint on growing expenditures. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(2), 197-216. doi:

- Greer, S. L. & Rauscher, S. (2011). Destabilization rights and restabilization politics: policy and political reactions to European Union healthcare services law. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(2), 220-240. doi:

- Holden, C. (2009). Exporting public–private partnerships in healthcare: export strategy and policy transfer. Policy Studies, 30 (3), 313-332. doi:

- Kaminska, M. E. (2013). The Missing Dimension: A Comparative Analysis of Healthcare Governance in Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 15(1), 68-86. doi:

- Kennedy, P. (2015). The Contradictions of Capitalist Healthcare Systems. Critique, 43(2), 211-231. doi:

- Kuhlmann, E. & Burau, V. (2008). The ‘Healthcare State’ in Transition. European Societies, 10(4), 619-633. doi:

- Mills, G. R.W., Phiri, M., Erskine, J. & Price A. D. F. (2015). Rethinking healthcare building design quality: an evidence-based strategy. Building Research & Information, 43 (4), 499-515. doi:

- Olimid, A. P. (2015). Civic Engagement and Citizen Participation in Local Governance: Innovations in Civil Society Research. Revista de Științe Politice. Revue des Sciences Politiques, 44, 73-84.

- Parekh, N., Mitis, F. & Sethi, D. (2015). Progress in preventing injuries: a content analysis of national policies in Europe. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 22(3), 232-242. doi:

- Permanand, G. & Mossialos, E. (2005). Constitutional asymmetry and pharmaceutical policy-making in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 12(4), 687-709. doi:

- Petmesidou, M., Pavolini, E. & Guillén A. M. (2014). South European Healthcare Systems under Harsh Austerity: A Progress–Regression Mix?. South European Society and Politics, 19(3), 331-352. doi:

- Polese, A., Morris, J., Kovács, B. & Harboe, I. (2014). ‘Welfare States’ and Social Policies in Eastern Europe and the Former USSR: Where Informality Fits In?. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 22(2), 184-198. doi:

- Toth, F. (2010). Is there a Southern European Healthcare Model?. West European Politics, 33(2), 325-343, doi:

- Vasev N. & Vrangbæk, K. (2014). Transposition and National-Level Resources: Introducing the Cross-Border Healthcare Directive in Eastern Europe. West European Politics, 37(4), 693-710. doi:

- Vollaard H., Van de Bovenkamp H. & Martinsen D. S. (2016). The making of a European healthcare union: a federalist perspective. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(2), 157-176. doi:

- Whitehead, M. M. (1999). Where Do We Stand? Research and Policy Issues Concerning Inequalities in Health and in Healthcare. Acta Oncologica, 38(1), 41-50. doi:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 July 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-026-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

27

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-893

Subjects

Teacher training, teaching, teaching skills, teaching techniques,moral purpose of education, social purpose of education, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Georgescu, C. M. (2017). Healthcare Policy-Making Within Eu Governance: A Content Analysis Of Media Coverage. In A. Sandu, T. Ciulei, & A. Frunza (Eds.), Multidimensional Education and Professional Development: Ethical Values, vol 27. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 221-233). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.07.03.29