Abstract

This article takes studying the impact of tax consolidation on oil companies’ tax burden as its focus. Oil companies are crucial for the Russian economy while oil and gas money are as well important for the Russian budget. Besides, a lot of oil companies being major taxpayers have had the opportunity to consolidate corporate profit tax since 2012. The article's goal is to analyze the results of creating consolidated groups of taxpayers for tax burden in terms of corporate profit tax exemplified by oil companies in order to assess the importance of profit tax consolidation as a way of reducing corporate profit tax. Upon analyzing the data provided by the Federal Tax Service of Russia and 2010-2015 oil companies' financial reports, it is possible to conclude that the largest tax burden falls on fossil fuel industry in comparison with other industries what can be explained first of all by the mineral extraction tax. Corporate profit tax burden for most oil companies in 2014 accounted for 5% of revenue. At the same time, profit tax burdens on consolidated groups of taxpayers producing oil vary a lot; in 2012, the general trend was falling, but then it started to grow again. Thus, it is impossible to state that tax obligations and corporate profit tax burden have significantly decreased as a result of creating consolidated groups of taxpayers for oil producers. Quantitative analysis of money spent for paying the profit tax might be interesting for describing consequences of creating consolidated groups of taxpayers.

Keywords: Tax burden; corporate profit tax; tax consolidation; consolidated group of taxpayersoil companies

Introduction

Russian oil companies are strategically important for both government revenues and the Russian economy on the whole. According to the Ministry of Finance, oil and gas revenues accounted for 11% of GDP in 2014 and a third of all tax revenues of the budget (oil and gas revenues included the mineral extraction tax for oil and gas, excise duties on oil products as well as export charges for oil, gas and oil products). At the same time, according to the Federal Tax Service of Russia (1-HOM form: Taxes and Charges Revenue Returned to the Consolidated Budget of the Russian Federation per Main Economic Activities), the share of crude oil and gas producing companies and providing services in this business area was sustainably growing since 2010 in terms of tax amounts paid and accounted for approximately 30% in 2015 (see Table

Transfer pricing and deals among related persons have been under stricter control in Russia since 2012. This became a ground for paying profit tax as a part of a consolidated group of taxpayers (CGT) which can be entered voluntarily in case of fulfilling conditions. Russian legislation gives a most detailed list of requirements to a group for organizing a CGT. These include business line, financial health, and a continuous operation of group members (Bannova, 2016). Direct or indirect participation by a company in the capital of other companies should be at least 90%. The total amount of taxes paid (VAT, excises, corporate profit tax, and mineral extraction tax) should comprise at least 10 billion roubles. The total revenue of the group should comprise at least 100 billion roubles. The total assets value of the group should comprise at least 300 billion roubles. There are significant differences in requirements for consolidation in Russia in comparison with the legislation of most countries that assume group taxation (Bannova et al., 2015). Other countries put forward requirements exclusively concerning a participation share of every company within a group without other numeric limitations such as revenue, assets, taxes paid and so on (Ting, 2012; Khaperskaya et al., 2016; Bannova et al., 2016).

These are the advantages of the consolidating corporate profit tax (Fedenkova et al., 2016; Koroleva, 2015):

- there are no reasons for a company to opt for tax evasion scenarios involving transfer pricing. It is no longer necessary for the state to perform complex control over transfer pricing among related entities that have created a consolidated group of taxpayers.

- negative consequences of tax base migration among the regions of the Russian Federation are mitigated;

- conditions are provided to reduce costs for taxpayers by means of delegating the duty to assess and pay profit tax to one and the same person in charge who is a member of the consolidated group of taxpayers. Besides, a number of procedures involving members of a group of taxpayers is put together by the state in terms of tax management;

- integrated structures are provided with an impetus that facilitates competitiveness among closely related manufacturers on the internal and international market.

Thus, creating a CGT assumes lower costs for the state and taxpayers, but at the same time, a lot of studies point out lower profit tax revenues received from CGT. The article's goal is to analyze the results of creating consolidated groups of taxpayers for tax burden in terms of corporate profit tax exemplified by oil companies in order to assess the importance of profit tax consolidation as a way of reducing corporate profit tax.

Methodology

The development process of methods for assessing tax burden has a long history (Atrostic, and Nunns, 1991). First of all, tax burden is considered a characteristic that allows comparing tax systems of different nations (Kiss et al, 2009) and in different conditions (Bovi, 2008; Liu, and Altshuler, 2013). There are methods for assessment (OECD, 2000) and comparison analysis of tax burden for various categories of population (Razin et al., 2002) and different business activities (mainly Paying taxes, 2015; as well as Lammersen, and Schwager, 2005).

Attempts have been made to assess tax burden for separate industries (Li and Zhu, 2014: Radev, 2013) including oil companies on the whole (Harper, 1963), as well as assessing tax burden after tax consolidation (Spengel, & Oestreicher, 2012; Roggeman et al., 2014). Simultaneously, such methods have their own differences depending on the country they are practiced in which are also affected by data accessibility in terms of nationwide financial reports. Russian studies suggest methods with detailed analysis of different costs caused by taxation, on one hand, and financial indexes related to these costs on the other. One of the methods used by the Federal Tax Service of Russia stands aside from all the rest sophisticated comprehensive ones. It compares taxes paid by a company with company's revenue. The limitations inherent to this method are obvious (not all tax costs and other similar costs fall under the 'taxes paid' category, on the one hand, and also company revenue is not the most informative index for many industries and business activities, on the other). However, it is without doubt easy to use and provide a definite result. Due to the fact that we are going to use data by the Federal Tax Service on tax burden per activity, profit tax burden will be calculated as a relation of profit tax paid to the revenue over the period in question.

In order to analyze tax burden of Russian extracting companies (under the category of 'fossil fuel industry') and to compare it with other business activities, we are going to analyze tax burden data per industry over 2010-2014 that was provided by the Federal Tax Service within the Concept of the on-site tax audit schedule system. These indexes of tax burden include all the taxes paid by a company.

The focus of the next stage of our study will be reduced to corporate profit tax burden of companies that are in fossil fuel business. This index will be calculated according to the data provided by the SPARK-Interfax for all the Russian companies that are in extracting stone coal, brown coal and peat, crude oil and natural gas, providing services in these spheres (that fall under the economic activity classified by the Russian authorities as 'fossil fuel extraction') as of 2014. The data selection includes 6,451 companies.

At the final stage of the study, fossil fuel companies from the list of companies that have formed CGT will be listed separately. Based on the financial reports analysis of the groups of companies over 2011-2015, profit tax burden will be calculated, and a conclusion will be made regarding changing trends in tax burden over the given period.

Results and Discussion

3.1 Tax burden of oil companies in comparison with other businesses

According to the Federal Tax Service, the highest tax burden per industry has been recorded for the fossil fuel business (table

In 2014, the tax paid by the companies extracting crude oil and natural gas and providing services in related spheres (1-HOM form: Taxes and Charges Revenue Returned to the Consolidated Budget of the Russian Federation per Main Economic Activities) accounted for 75.6% of all the taxes paid while profit tax equaled only 10.6%. Tax burden dynamics for most other industries remains at the same level as previously or decreases (up to 4 percentage points for hotels and restaurant with an average of 10-34%). However, tax burden for fossil fuel extraction showed growth in 2010-2014 for 9.4 percentage points or by 28.8%.

3.2 Oil companies tax burden in 2014

Even though the Federal Tax Service gives a picture of the general tax burden trend, data for separate companies can differ a lot from the average value.

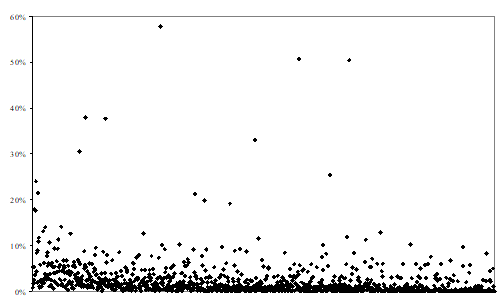

In order to analyze profit tax burden for separate companies, we have analyzed 6,451 fossil fuel companies in 2014. On the SPARK-Interfax database containing company reports, there was information on profit taxes paid by 1,250 companies (19.4% of the total number of companies studied); 53 companies out of this number did not provide information on company revenue, information for 5 companies was incomparable. Thus, the final selection of oil companies included 1,192 for assessing their tax burden. Tax burden for the selection is shown in fig.

The average value of tax burden for the studied companies was 2.47% with standard deviation of 4.54%. As for the distribution of the results, tax burden for most companies (1,032 out of 1,192) was from 0% to 5%, it was 5-10% for 121 companies, 10-20% for 25 companies and over 20% for 14 companies.

Thus, profit tax burden for fossil fuel companies is significantly lower than the average tax burden (45.6%); at the same time, there are different profit tax burdens for separate companies.

Oil companies within CGT

The limitations mentioned above for creating consolidated groups of taxpayers by Russian companies resulted in 2012 in creating only 11 consolidated groups; there were 16 of them by the end of 2014 when a temporary moratorium on creating CGT was declared. The groups include mainly large oil and gas holding companies, as well as those from the metal and telecom industries. Five of them are directly involved into oil extraction (table

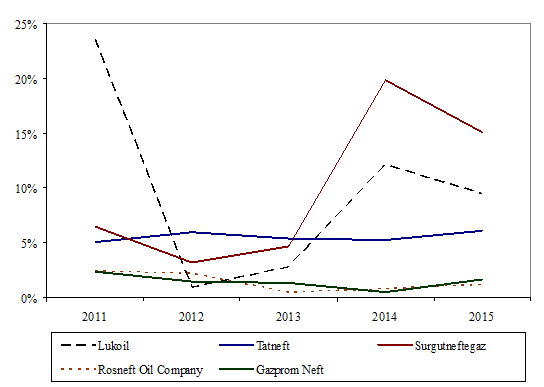

Annual financial reports prepared according to the Russian accounting standards were used in order to compare profit tax burden before and after tax consolidation over the period from 2011 (before) to 2012-2015 (after). Profit tax burden for oil companies that formed CGTs is shown in fig.

PJSC Lukoil showed the highest profit tax burden before forming CGTs that accounted for 24% of revenue, Tatneft and Surgutneftegaz showed 5-6.5%, Rosneft and Gazprom Neft showed approximately 2.5%. Four out of five companies in question entered a CGT in 2012; Lukoil showed a decrease in tax burden down to 1%, Rosneft showed 2.2%, Surgutneftegaz showed 3.2%. At the same time, Tatneft's tax burden increased from 5.1% to 6% while Gazprom Neft's tax burden decreased by 0.9 percentage points without creating a CGT (its tax burden decreased further by 0.2 percentage points after the creation of a CGT in 2013). However, profit tax burden has started to show growth among all the companies that formed CGTs since 2014 except Gazprom Neft.

Thus, a conclusion can be made that even if the creation of CGT's resulted in lowering profit tax burden, the effect it provided was neither significant nor long-lasting. It is much more likely that oil companies tax burden is more affected by other macroeconomic factors.

Conclusion

According to the Ministry of Finance of Russia, there is a sustainable growth of profit tax for companies that did not pay it as a result of creating CGT's (from 8 billion roubles in 2012 to 65.1 billion roubles in 2014). However, according to the analysis of the profit tax burden of oil companies before and after the consolidation, it is impossible to state that there was a significant decrease of tax burden as a result of the CGT creation in the oil extracting industry. At the same time, this can result from rather inadequate assessment of tax burden that did not include additional tax costs beside the mentioned profit tax (including alternative ones). The analysis of changes in profit tax trends for oil companies since 2010 can poses interest for comparing its data with current results.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Russian Foundation for Humanities (RFH) in the frame of the project for scientific studies (Modeling of conditions of the consolidation of tax liabilities to mitigate the conflict of interest of the state and taxpayers), project No. 15-32-01341.

References

- Atrostic B. & Nunns, J. (1991) Measuring tax burden: a historical perspective. Fifty Years of Economic Measurement: The Jubilee of the Conference on Research in Income and Wealth, 343-420.

- Bannova, K., Pokrovskaia, N., Dyrina E., Rigakina T. & Koroleva N. (2016) Consolidated group of taxpayers in different countries: conditions and restrictions comparison. Innovation Management and Education Excellence Vision 2020: from Regional Development Sustainability to Global Economic Growth, Proceedings of the 27th IBIMA conference in Milan, 430-1436.

- Bannova, K.A. (2016) Consolidated group of taxpayers as the way of sustainable of economics. Innovation Management and Education Excellence Vision 2020: from Regional Development Sustainability to Global Economic Growth, Proceedings of the 27th IBIMA conference in Milan, 1774-1780.

- Bannova, К., Ryumina Ju., Balandina A. & Pokrovskaia N. (2015) Consolidated taxation of corporations, STT.

- Bovi, M. (2008) Measuring tax burdens in the presence of non observed incomes. Economics Bulletin, 5 (10), 1-6.

- Fedenkova, A., Pokrovskaia, N., Khaperskaya, A. & Dyrina E. (2016) The consolidated groups of taxpayers in the context of social responsibility in Russia. Innovation Management and Education Excellence Vision 2020: from Regional Development Sustainability to Global Economic Growth, Proceedings of the 27th IBIMA conference in Milan, 563-567.

- Harper, J. (1963) The tax burden of the domestic oil and gas industry. Petroleum Industry Research Foundation.

- Khaperskaya, A., Pokrovskaia, N., Ivanov, V. & Bannova, K. (2016). The scope of corporate profit tax consolidation: the effect of changing the CGT entry threshold. Information Technologies in Science, Management, Social Sphere and Medicine (ITSMSSM 2016) Proceedings, 344-348.

- Kiss, G., J´drzejowicz, T. & Jirsákova, J. (2009) How to measure tax burden in an internationally comparable way? National Bank of Poland Working Paper No. 56.

- Koroleva, L. (2015) The role of consolidated groups of taxpayers in providing innovative breakthrough: to be or not to be. Journal of Tax Reform, 2-3, 177-193.

- Lammersen, L. & Schwager, R. (2005) The Effective Tax Burden of Companies in European Regions: An International Comparison. ZEW Economic Studies, Springer.

- Li, X.-J.& Zhu, Y.-K. (2014) An empirical study on tax burden and performance of mining enterprise in China. China Population Resources and Environment, 24 (2), 149-153.

- Liu, L. & Altshuler, R. (2013) Measuring the burden of the corporate income tax under imperfect competition. National Tax Journal, 66 (1), 215-238.

- OECD (2000), Tax Burdens: Alternative Measures, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Radev, J. (2013) Distribution of tax burden in the gas sector in Europe. Ikonomicheski Izsledvania, 22 (2), 109-130.

- Razin, A., Sadka, E. & Swagel, P. (2002) Tax burden and migration: A political economy theory and evidence. Journal of Public Economics, 85 (2), 167-190.

- Roggeman, A., Verleyen, I., Van Cauwenberge, P. & Coppens, C. (2014) Impact of a common corporate tax base on the effective tax burden in Belgium. Journal of business economic and management. 15 (3), 530-543.

- Spengel, Ch & Oestreicher, A. (2012) Common Corporate Tax Base in the EU. Impact on the Size of Tax Bases and Effective Tax Burdens. ZEW Economic Studies, Springer.

- Ting, A. (2012) The Taxation of Corporate Groups Under Consolidation: An International Comparison. Cambridge University Press.

- World Bank Group (2015) Paying taxes 2016. 10th edition.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

20 July 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-025-9

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

26

Print ISBN (optional)

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1055

Subjects

Business, public relations, innovation, competition

Cite this article as:

Pokrovskaia, N. V., Bannova, K. A., & Kornyushina, V. S. (2017). Tax Burden of Russian Oil Companies after Tax Consolidation. In K. Anna Yurevna, A. Igor Borisovich, W. Martin de Jong, & M. Nikita Vladimirovich (Eds.), Responsible Research and Innovation, vol 26. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 776-783). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.07.02.100