Abstract

The teacher, one of the essential resources in the teaching-learning process, is expected to permanently attune to latest professional developments, and in-service training is supposed to serve this purpose. Moreover, teacher education, as a whole, directly influences the results that students might achieve. Starting from these assumptions, as well as from the international reports focusing on these variables, we noticed that the Romanian educational system is characterized by an obvious discrepancy: (very) well trained teachers, according to their own perceptions, and (very) low prepared students, according to the results they obtained in international assessments. Thus, our paper aims at analyzing the causes lying beneath this gap, in order to get some further insight into the current situation. Our conclusions point to the weaknesses, the shortcomings and the deformations of the Romanian professional development system for teachers (part of the Romanian in-service training system). We suggest that both legislative and methodological changes are badly required so that all Romanian stakeholders (training providers, teacher educators, teachers etc.) could fully benefit from qualitative and effective professional development, which could indeed ensure long life learning.

Keywords: Teacher educationin-service trainingprofessional development for teachersteacher educators

Introduction

No matter the trends characterizing education, the teaching-learning equation has always included

two main elements: the learner and the teacher. Diachronically, their weight has varied according to the

ideas underlying educational theories and, gradually, the learner has started to play the main role.

Nevertheless, the teacher’s importance should not be overlooked, as student’s achievements depend on

the teacher’s ability to teach. Both pre- and in-service training help teachers gain teaching abilities. Metaphorically, one could

say that pre-service training lays the foundation of this profession and in-service training puts the

finishing touches on it. The latter ‘is at the heart of the European strategy for improving the quality of

education’ (European Commission, 2015, p. 55) and our paper deals with professionaldevelopment (PD),

which is part of in-service training according to Romanian educational standards.

The starting point of our research stems from the obvious discrepancy between the Romanian

teachers’ opinion on themselves (2013 TALIS National Report) and Romanian students’ 2012 PISA

scores: Romanian teachers considered themselves (very) well trained professionally; Romanian students’

scores were below the average obtained by OECD countries. Although factors such as school conditions,

school attendance, out-of-school learning experiences and family resources could account for Romanian

students’ poor performance, the teacher variable also carries some weight. Consequently, our paper aims

to investigate the causes leading to the mismatch between teachers’ perceptions and their students’ results.

In part one, this paper points to relevant literature and research/reports covering the issue of teacher PD in

Europe, with a special focus on the Romanian case. Then, the second part deals with methodology,

research findings and discussions, and the final part presents the conclusions of our investigation,

introducing possible solutions for the problems that have been identified.

Teacher Professional Development: A Brief Outline

Teacher education is and should be viewed ‘as a life-long experience for teachers, a continuum that

goes from their initial education to their retirement’ (Musset, 2010, p. 45). Thus, no matter how relevant

and effective pre-service training might be, in-service training acquires paramount importance to maintain

and improve the quality of education.

European countries have scrutinized the needs, participation, enablers, and barriers to PD in order

to identify the best, the most flexible and the most appropriate ways to equip teachers with the necessary

skills, so that they could be efficient in the classroom and could smoothly attune to the growing demands

of the teaching profession. In-service training systems in Europe are, more often than not, country specific

as far as the following aspects are concerned: training means; course topics; course length; potential

rewards for teachers attending the courses; status (in-service training is either a right or an obligation, or

both) (EC, 2015; European Union, 2014; Mâță & Boghian, 2012; Musset, 2010; Valencic Zuljan &

Vogrinc, 2011; Șerbănescu, 2011; Iucu, 2007). Nevertheless, at European level, in-service training of

teachers represents a major priority, as it directly influences the overall quality of the national education

systems.

In Romania, in-service training is both a right and an obligation (2011 National Education Act,

Art. 245 (1)) and the necessary complementarity between the pre- and in-service training is laid down in

Romanian legislation: ‘In-service training and pre-service training are conceived as interdependent

processes, which should be characterized by a high degree of interaction and self-adjustment, meant to

attune teacher training to system dynamics in education’ (Ministerial Decree No. 5561/2011, Art. 4 (2)).

Similarly, as in other European countries, Romanian in-service training ‘continues, refines and attunes pre-service teacher education, offering added value as circumstances keep changing and new demands

emerge, different from the ones characterizing pre-service teacher education’ (Iucu, 2007, p. 28).

Romanian in-service training is divided into career development (to reach the maximum status of

their career development, novice teachers are required to complete three stages: qualified teacher, teacher

certification level 2 and teacher certification level 1) and PD (teachers are bound to attend in-service

training courses in order to gain 90 professional transferable credits within 5 years). Whereas teacher

career development focuses on teacher’s reaching specific degrees of scientific and methodological

competence, PD aims at systematically equipping teachers with those skills that could help them attune to

the latest trends in their field (both scientifically and methodologically).

Most Romanian teachers enroll in career development as permanent teacher certification not only

provides professional stability, but also raises their salaries, very much like teacher certifications (levels 1

and 2), whereas PD is rather optional (although Romanian legislation specifies that 90 professional

transferable credits shall be acquired by teachers after they have become certified teachers level 1, there is

no reference to the penalties that they might get if they choose not to enroll in any PD course at all). Thus,

it is up to each individual teacher whether he/she chooses to attend PD courses in order to get the 90

professional credits, as there is no immediate reward (only indirect and unguaranteed rewards, e.g.

accumulating scores required when applying for: teaching staff transfer; becoming a member of the

national body for professionals in educational management) and no financial compensation, as, in most

cases, teachers themselves pay for the courses they attend (OECD, 2014a, p. 98).

In contrast with this situation, most Romanian teachers consider PD to be an obligation, a duty,

and, very rarely, acknowledge it to be their right (Iucu, 2007, p. 108), and this makes PD become highly

formal and even perfunctory (Jigău, 2008; Velea & Istrate, 2011; Stan, Suditu & Safta, 2011; Masari,

2013; Popa & Bucur, 2015; Zoller, 2015).And yet, many Romanian teachers are eager to comply with

this obligation: 83% of lower secondary teachers report having undertaken a PD course in the 12 months

prior to the survey (OECD, 2014b), percentage which is, nevertheless, below the 88% OECD average

(OECD, 2014a).

Although,apparently, it is still difficult to account for the relevance of PD for the individual

teacher or for his/her school (Șerbănescu, 2011, p. 88), ‘empirical evidence increasingly shows the

positive impact of teachers’ PD on students’ scores’ (OEDC, 2014a, p. 97). Even if Romanian students

failed to rank among the best in international assessments (OECD, 2013), considering the content of the

discipline they teach, as well their methodological skills, Romanian teachers have a very high opinion of

themselves as compared to the international average (National Assessment and Examination Center,

2014). The aspects listed above make up a contradictory picture, which has prompted us to ask ourselves:

Methodology

Our questionnaire-based survey was conducted in 2015-2016 school year: 200 subjects, primary

and secondary school teachers participated in the survey (Prahova county – 176, Dâmbovița county – 15,

Giurgiu county – 4, Ilfov+Bucharest – 7). One of the items provided the following identification data for

the survey participants (gender was excluded, as only 6 male subjects, all from Prahova county, took part in the survey): (A)

– 188 (94.0%), substitute teacher – 12 (6.0%); (C)

teacher – 30 (15.0%), certified teacher level 2 – 27 (13.5%), certified teacher level 1 – 130 (65.0%); (D)

(7.5%).

At the time of our investigation, all the subjects were enrolled in a PD programme. Moreover, to

get some further insight, we organized 6 focus groups (36 respondents, each group comprising at least one

representative from the 6 counties mentioned above).

Besides the identification item, our questionnaire comprised 6 more items (3 closed, 3 open),

correlated with the main objective of our research: identifying Romanian teachers’ opinion on the current

PD system (

Romania; the weaknesses of the PD system in Romania; how the knowledge and the skills acquired by

teachers during the PD courses could be implemented; the kinds of competences that teacher educators

may require.

Findings and Discussions

Analyzing the structure of our group of respondents, and correlating it with the survey data and

group interviews, we consider that the following aspects are worth being given some explanations:

there are more survey participants that come from rural areas because (1) they are motivated to attend PD courses as their chances of occupying a better position (closer to home or in an urban area) increase and (2) public administration institutions in rural areas are more likely to pay the course fees for the teachers in their schools (41 teachers out of the 53 teachers, who received sponsorship to attend the PD course, come from rural areas);

many of the survey participants come from Prahova County because the course they attended took place in the county capital, Ploiești. The course attendants belonging to the other counties chose to enroll because (1) they could get easier to Ploiești than in their own county capital (the reason given by respondents from Dâmbovița); (2) the moment they enrolled there was no course / no appealing course was organized in their county of residence;

the majority of the survey participants are older than 36 because (1) younger teachers are usually in the process of gaining their qualification/ certification (exams which belong to the career development stage, thus younger teachers might have already obtained or be about to obtain the required number of transferable professional credits) and (2) senior teachers are more likely to enjoy the benefits granted by PD (e.g. the possibility to occupy a management position, to become a teacher methodologist in the school inspectorate or an expert in educational management or to get a financial reward based on his/her professional merits) as compared to their younger counterparts;

the big number of tenured teachers suggest (1) tenured teachers’ high interest in PD and, obviously, (2) the low interest exhibited by substitute teachers, either because their status is temporary (they will leave the educational system as soon as a better opportunity occurs) or because they want to become certified teachers in the near future (PD does not really help them achieve this objective, as it involves passing a national exam).

The answers given by our respondents on how they got informed about the PD course they chose to attend (by e-mail sent by teacher educators/ training providers to prospective trainees or to school offices; from colleagues or acquaintances in informal discussions; from colleagues in formal contexts – e.g. subject-oriented methodological workshops) suggest that promoting and disseminating PD courses is not a very well organized activity. Nevertheless, 164 of our survey participants (82%) took part in such a program in the last five years, percentage very close to the one included in the OECD report on Romania (2014b), indicating the high level of interest that Romanian teachers seem to have in PD.

Being asked about their reasons for enrolling in the PD course and being given the possibility to enumerate one or more answers, the survey participants pointed to: the possibility to develop professionally (66 responses); the wish to accumulate 90 professional transferable credits (64 responses); the convenient schedule of the program – organized at the weekend as compared with other programs available only during the week (51 responses); the convenient price of the PD course (36 responses); the difficulty of enrolling in fully-sponsored PD courses, which are in very high demand (29 responses); the possibility of applying for a better teacher position during the transfer period (17 responses); the possibility of joining the national body of experts in educational management – getting 60 credits in educational management is a prerequisite to becoming a member of this group of experts (16 responses); the location of the PD course (13 responses); the possibility of complying with the criteria for obtaining a financial reward for their professional merits (12 responses); the possibility of getting the position of teacher methodologist in the school inspectorate (1 response). To sum up, we noticed that, out of the 305 responses, the ones referring to intrinsic reasons (individual PD needs) are in obvious minority, as most responses are in close connection with the already listed characteristics of PD in Romania: on the one side, it is mandatory (more like a constraint), independent of personal needs, formal and, on the other side, it represents a prerequisite for reaching personal objectives.

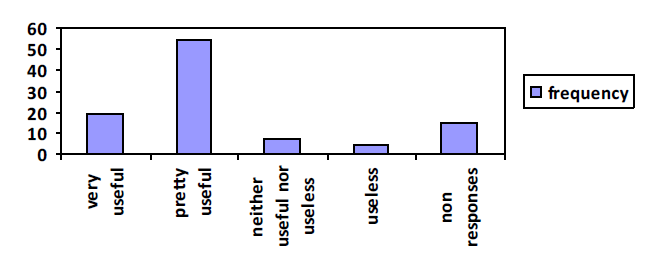

As for the usefulness of the various PD courses they have attended, for their present activity in the classroom, our subjects’ answers indicate their moderate satisfaction:

The fact that they are not fully convinced that taking part in the PD program will positively

influence their didactic activity resurfaces with the next question (

Our respondents’ views are relevant and we divided them into four groups, closely related to the aims of

our investigation:

(1) the general features of PD in Romania – its high degree of formality (‘

teacher level 1, rural area, Giurgiu; ‘

provisions regulating the teachers’ attendance (

the courses on offer (

and a prerequisite for career advancement (

certified teacher level 2, rural area, Prahova;

(2) PD weaknesses in Romania – the content is too general, theoretical, obsolete, instead of being

customized in order to be compatible with the participants’ curricular area(s) or the age characteristics of

their students (

Prahova;

certified teacher level 1, rural area, Dâmbovița;

qualified teacher, rural area, Prahova); more flexibility is needed as far as time and place of the training

courses are concerned (

teachers during the PD courses – the poor conditions in Romanian schools (lacking technical equipment,

space, etc) as well as the traditional mentality deeply rooted in some teaching staff (

teacher level 2, rural area, Dâmbovița profesor).

(4) the profile of the teacher educator (

Conclusions and recommendations

As our findings show, PD problems have evinced the weaknesses related to legislation,

curriculum, methodology, thus creating the proper circumstances to make the teachers participating in PD

courses pretend that they are motivated and willing to attend the training sessions. Even if, more than a

decade ago, Romanian education specialists tried to sound the alarm so that appropriate measures would

be taken (Potolea, & Ciolan, 2003; Bârzea, et al., 2006), so far, no important steps have been taken to

improve the PD system.

In our opinion, the most serious problem is related to the quality of teacher educators. In

education, at any level, the most important resource is the individual:

people can train people; so, without investing in people, no beneficial changes could occur in education or

for education. In order to achieve better learning outcomes, students have to rely on their teacher (=their

most important learning resource), and, similarly, teachers should be able to get the most from their

teacher educators, as teachers’ teachers are supposed to represent valuable learning resources. That is why

we consider that, in Romania, efforts should be channeled towards supporting teacher educators, going

along the lines laid down at EU level (EC, 2013). We suggest that PD research in Romania should focus

on identifying the most suitable ways of training and selecting teacher educators, on defining the profile of the teacher educator, in order to deliver teacher educator PD programs in accordance with our national

context, given the Romanian conditions. In our opinion, specific, national-oriented approaches are

needed, so that Romanian frameworks and policies regulating PD could be devised.

Although the group of subjects we investigated was small, it covered a wide range of situations,

which gives a certain weight to our conclusions. Our findings reemphasized the problems already

identified by Romanian researchers focusing on PD, pointing to the importance of reconsidering the

teacher element in the education equation. PD, as integer part of in-service training, represents one of the

most direct ways of improving teacher quality and, unfortunately, in Romania, this profession is currently

in freefall. We consider that by solving teacher-related problems, the rest of the education-related

problems could be alleviated. Thus, Romanian education could hope for better teacher educators and

better teachers, who could produce better students, who, eventually, will possess the skills and

competences to build up a brighter future for us all.

References

- Bârzea, C., Neacșu I., Potolea, D., Ionescu, M., Istrate, O., & Velea, L. S. (2006). National Report –

- Romania. In P. Zgaga (ed.), The Prospects of Teacher Education in South – East Europe. Ljubliana: University of Ljubliana, Faculty of Education,pp. 437-485.

- Centrul Național de Evaluare și Examinare (2014). Raport Național Talis 2013. Centrul Național de Evaluare și Examinare, Centrul Național Talis, http://www.rocnee.eu/Files/raport_talis_2012.pdf European Commission (2013). Supporting Teacher Educators for Better Learning Outcomes. Thematic Working Group ‘Teacher Professional Development’, from http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/education_culture/repository/education/policy/school/doc/support-teachereducators_en.pdf European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2015). The Teaching Profession in Europe: Practices, Perceptions, and Policies. Eurydice Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European. European Union (2014). Teaching Teachers: Primary Teacher Training in Europe – State of Affairs and Outlook. Brussels: European Parliament.

- Iucu, R. (2007). Formarea cadrelor didactice. Sisteme, politici, strategii. București: Editura Humanitas Educațional.

- Jigău, M. (coord.) (2008). Formarea profesională continuă în România. București: Institutul de Științe ale Educației.

- Legea Educației Naționale (2011). Monitorul Oficial al României, nr.18, Partea I, 10 ianuarie 2011. Masari, G. A. (2013). Kindergarten teachers' perceptions on in-service training and impact on classroom practice. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 76, 481 – 485.

- Mâță, L. & Boghian, I. (2012). The views of pre-primary and primary teachers regarding continuous teacher training in Romania. Journal of Innovation in Psychology, Education and Didactics, 16 (2), 127-134.

- Musset, P. (2010). “Initial Teacher Education and Continuing Training Policies in a Comparative Perspective: Current Practices in OECD Countries and a Literature Review on Potential Effects”.

- Papers, No. 48, OECD Publishing. OECD Education Working http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kmbphh7s47h-en OECD (2013). PISA 2012 Results: What Makes Schools Successful? Resources, Policies and Practices (Volume IV). PISA, OECD Publishing, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264201156-en OECD (2014a). Talis 2013 Results: An International Perspective on Teaching and Learning, OECD Publishing, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264196261-en OECD (2014b). Talis 2013 Results: An International Perspective on Teaching and Learning. Country Profile Romania, http://www.oecd.org/edu/school/TALIS-Country-profile-Romania.pdf

- Ordinul Ministrului educației, cercetării, tineretului și sportului nr. 5561/2011 pentru aprobarea Metodologiei privind formarea continuă a personalului din învățământul preuniversitar. Monitorul Oficial al României, Partea I, Anul 179 (XXIII) — Nr. 767 bis.

- Popa, O. R. & Bucur, N. F. (2015). What do Romanian primary school teachers think of the official curriculum? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 180, 95 – 103.

- Potolea, D., Ciolan, L. (2003). Teacher Education Reform in Romania. A Stage of Transition. In B.

- Moon, L. Vlăsceanu, & L. C. Barrows (eds.), Institutional Approaches to Teacher Education within Higher Education in Europe: Current Models and New Developments. Bucharest: UNESCO – CEPES, pp. 285-304.

- Șerbănescu, L. (2011). Formarea profesională a cadrelor didactice – repere pentru managementul carierei. București: Editura Printech.

- Stan, E., Suditu, M., & Safta, C. (2011). The teachers and their need for further education in didactics - An example from the Technology curricular area. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 11, 112–116.

- Valencic Zuljan, M. & Vogrinc, J. (eds.) (2011). European dimensions of teacher education: similarities and differences. Ljubljana: Faculty of Education; Kranj: The National School of Leadership and Education.

- Velea, S. & Istrate, O. (2011). Teacher Education in Romania: Recent Developments and Current Challenges. In M. Valencic Zuljan, J. Vogrinc (eds.). European dimensions of teacher education: similarities and differences. Ljubljana: Faculty of Education; Kranj: The National School of Leadership and Education, pp. 271-294.

- Zoller, K. (2015). Teachers’ Perception on Professional Development. PedActa, 5 (2), 15-21.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Popa, O., & Bucur, N. (2017). Beyond The Limits Of Professional Development For Teachers: The Romanian Case. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 818-826). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.99