Abstract

The challenge of this paper is to provide a comprehensive picture not only of the most important ideas on operational learning objectives technique, but also to propose an alternative scenario to it. A set of premises which assumes the status of arguments should be specified. First, there are two major drawbacks associate to the current scenario practiced for operationalization: it nurtures the backwash effect, implicitly validates a learning for evaluation. Secondly, the operationalization of objectives must be understood in relation with its essential function, that to specify the desirable performing that had a specific nature: are the result of learning associated with a sequence didactic called lesson. As a result, the statements must contain specific performing of the lesson, which generates a natural consequence: different lessons may not have identical finalities (objectives). Thirdly, in a learning regulated by the skills centered paradigm, the operationalization of objectives should be achieved at the level of competence’s components: knowledge, skills / abilities and attitudes. Because the homework should be considered part of the lesson, the teacher is entitled to exploit the homework as a student's opportunity to continue learning in the classroom, and this can and should be reflected in operationalization philosophy. Finally, it should not be ignored a reality: the most impressive statements which claiming to be operational objectives have not this quality, being incomplete. But they set up a real spider web which causes many negative effects, one of them being diminishing the quality of learning.

Keywords: Lessoncompetencieslearning experiencesperformance objectives

Introduction

The instructive role of teacher is to ensure student learning. To manage it. This initiative,

combined with other efforts in the area of classroom management can be defined as teaching. School

learning should be seen as an endeavour whose quality is assessed in relation to relatively precise

standards: the goals set out in the curriculum.

These statements, called competencies, forcing the teacher to design a specific training plan for

students. In the specialist language the competencies is named goals, because they have an increased level

of generality which does not facilitate an easy access to surprise and evaluate its. It is necessary,

therefore, a configuration of another set of functional milestones: learning objectives. The literature

confirms that these aims have a certain profile: to capture visible, measurable acquisitions.

The paper focuses on operationalization phenomenon because, on the one hand, considers as

inadequate the lack of specialists’ (theorists and practitioners) critical attention in a delicate period in

terms of curriculum. On the other hand, it attempts to offer an alternative to the traditional understanding

reasoned and building these goals. In addition, the conceptual approach is reported permanently to

another evaluation criterion: SMART attribute set that the aims of a lesson must prove it.

Paper Theoretical Foundation and Related Literature

A First Landmark: Conceptualisation and Operationalisation

The issue of operationalization objectives begins with a general statement (specific competence)

derived from other sets of statements, more general (the objectives of curricular cycles, the general

competencies). All coordinated to generate a final educational profile (the educational ideal). Any of

these statements provides images about what should be, but they invite at doubts about how it should be

done.

This is the challenge, methodological, but in the procedural sense. Why and how it should be done

at the microscopic level, that of the lesson? Ironically, the images are not clear, analytical, they hide

essential details. The cells of new construct (competence) are invisible. The teacher must go through

decoding way. A decoding of meanings that each competence posed as conceptual challenge.

This idea of operationalization assumes two basic categories: the concept and the

operationalization of a concept. For Ågerfalk (2004), the concept is always more abstract than its

operationalization and both need to be an explicitly stated linguistic aspect of the action knowledge under

scrutiny.

The operationalized concept can then be applied in practice whereupon consequences arise. To

summarize, one piece of knowledge can be instantiated and studied in (at least) four different shapes: as a

concept, as an operationalization of the concept, as an application of the operationalization, and as a

consequence of the application.

Conceptualization attributes means a clear understanding of a concept by specifying one or more

indicators that express the things that we think (Babbie, 2010). Conceptualization is refinement and

specification of abstract concepts and operationalization is developing procedures (operations) specific

research that will result in empirical observations representing these concepts in the real world (ibid).

A Second Landmark: The Learning Objectives and the Necessity to Operationalize Them

Ambrose and Bridges and Lovett and DiPietro and Norman (2010, pp. 3-6) define learning as a

process that leads to change, which occurs as a result of experience and increases the potential for

improved performance and future learning and identify seven principles of learning: students’ prior

knowledge can help or hinder learning; how students organize knowledge influences how they learn and

apply what they know; students’ motivation determines, directs, and sustains what they do to learn; to

develop mastery, students must acquire component skills, practice integrating them, and know when to

apply what they have learned; goal-directed practice coupled with targeted feedback enhances the quality

of students’ learning; students’ current level of development interacts with the social, emotional, and

intellectual climate of the course to impact learning; to become self- directed learners, students must learn

to monitor and adjust their approaches to learning.

In pedagogical literature, an important topic is the differences between the terms “learning

outcomes” and “instructional objectives”. Prideaux (2000) suggests: “Contemporary experienced

educators are now called upon to distinguish between outcomes and aims, goals and objectives”. Five

differences are highlighted which have practical implications for the curriculum developer, the teacher

and the student. These relate to: 1. the detail of specification; 2. the level of specification where the

emphasis is placed; 3. the classification adopted and interrelationships; 4. the intent or observable result;

5. the ownership of the outcomes (in Harden, 2002, p.151).

Learning objectives are statements of intent that describe what a student will be able to do as a

result of learning. They help to clarify, organize and prioritize learning and students are able to evaluate

their own progress and encourage them to take responsibility for their learning (Saul, Hofmann, Lucht &

Pharow, 2011, p.22).

Objectives define “where you are headed and how to demonstrate when you have arrived”

(Kaufman, 2000, p.44), emphasizing the end outcome or results that are intended to be exhibited by the

learner. According to Mager (1984), objectives are critical in selecting appropriate materials and

procedures, promoting instructor ingenuity, providing consistent and measurable results, setting goal

posts for students, and realizing instructional efficiency (in Yamanaka & Wu, 2014, p.75)

Kemp (2001) defines an instructional objective written from a behavioural perspective as “a

precise statement that answers the question, ‘What behaviour can the learner demonstrate to indicate that

he or she has mastered the knowledge or skills specified in the instruction?’” Writing “precise”

instructional objectives can be challenging but offers instructional designers clear, measurable goals to

which to guide their instructional design (in McLeod, 2003, p.37).

Educational objectives means an explicit formulations of the ways in which students are expected

to be changed by the educative process (Bloom, 1981, 26). Moreover, when students have clear

objectives, they are more likely to seek feedback to close the gap between their current understanding or

skill and the desired goal (Hattie & Timperly, 2007).

Specifically, when students set their own goals, they take responsibility and ownership of their

learning goals. Such goal-directed behavior that results from goal setting is empowering and proactive

(Elliot & Fryer, 2008). Research has shown that proactive actions increase sense of agency: a recent fMRI

study found that self-determined behavior of goal setting is indeed closely related to people’s sense of

agency and correlated with increased intrinsic motivation (Lee & Reeve, 2013). Setting goals can be

especially important for students with low achievement motivation.

Drafting learning outcome objectives for the development of desirable feelings, beliefs, attitudes,

or values is difficult. (…) when you are teaching abstract states as attitudes, you can only know whether

you succeeded by observing learners doing something that represents the meaning of these abstractions

(Houlden, Frid, & Collier, 1998, p.330).

Merriam and Caffarella (1999, p.251) identify three assumptions all behaviourists such as Mager,

Skinner, Thorndike and Watson share about the learning process. First, observable behaviour rather than

internal thought processes is the focus of study; in particular, learning is manifested by a change in

behaviour. Second, the environment shapes behaviour; what one learns is determined by the elements in

the environment, not by the individual learner. And third, the principles of contiguity (how close in time

two events must be for a bond to be formed) and reinforcement (any means of increasing likelihood that

an event will be repeated) are central to explaining the learning process.

Hattie (2014, p.101) identifies two parts of goal-oriented learning process: clarity of educational

objectives and the set of criteria for success. Both must be transparent for students. According to Hattie

(idem, pp.101-102), "effective teachers successfully plan a lesson by choosing objectives that are

sufficiently stimulating and by organizing learning situations that will help students achieve these goals."

The results of studies on the impact of objectives' setting (Wisey & Okey, 1983, Lipsey & Wilson,

1993; Walberg, 1999) confirms its importance: the average size of the effect is between 0.40 and 1.37,

and progress (percentile) is between 16 and 41 (in Marzano, 2015, p.25).

Author’s Contribution on the Existing Theory and Practice in Educational Field

The operationalization of the objectives is a step which specifies the performing set of anticipated

proposed for a lesson. Performing constitutes a concrete and measurable behaviour, result of school

learning experiences. Lesson is a learning experience that takes place over a project whose beginning and

end are formulating the objectives and evaluation of its. Performing formulation shall be in accordance

with pedagogical sense/ reason.

In previous papers (Petre 2013; Petre, 2014; Petre, 2015) it has been proposed an alternative way

to understand the lesson, as a school learning experience: "A functional unit motivated and meant to

produce performing indicated by operational objectives" (Petre, 2015, p.206). The definition tries to

capture some essential attributes of a lesson:

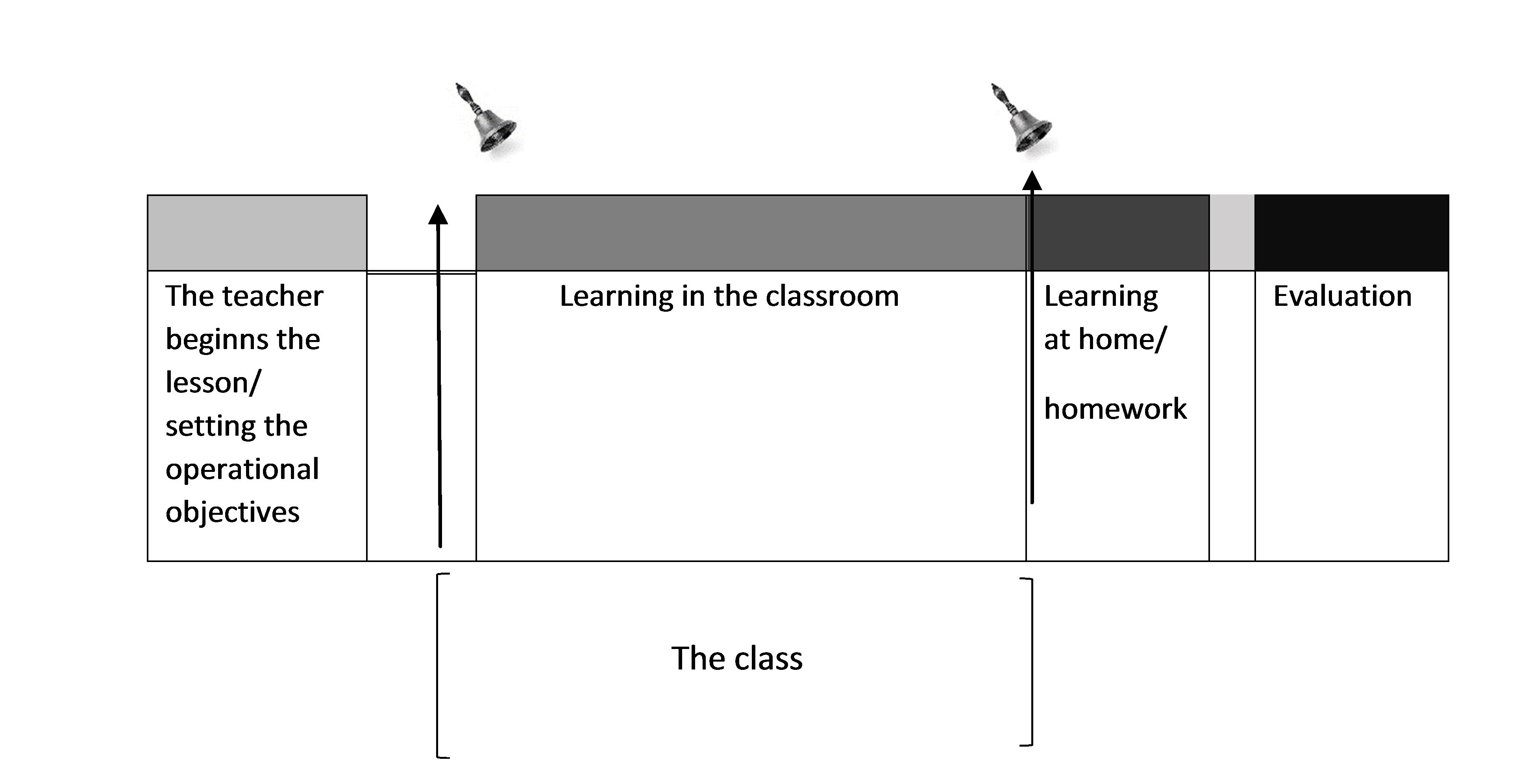

- lesson starts from the moment of formulating the specific aims (operational objectives) and ends

when these are verified through evaluation (Petre, 2014)

- there are two moments of the beginning of the lesson: one for teachers and one for students; for

the teacher, the lesson begins from the moment of finalizing the set of operational objectives (and the

event is before class). For students, the lesson starts since they discover these expectations formulated by

the teacher,

- the lesson ends when the teacher asks the student to prove performing. And this requires an

evaluative, self-evaluative or inter-evaluative effort,

- the school learning experience specific for a lesson is not limited to learning class, but is

continued and is completed by learning at home; this second experience is called homework,

In conclusion: a. the lesson has four stages (Petre, 2014, p.158):

b. temporally, the lesson does not overlap with class time; a lesson does not have the same points in time as class time (ibidem):

Author’s Contribution on the Topic

The references of pedagogical logic for formulating the performing behaviour specific to a lesson

(operational objectives) are likely genetic and functional, typological and structural. The proposed

analysis is a comprehensive, but organized according to the structural dimension. A very popular topic in

the pedagogical literature is the operationalization of objectives. Therefore, a history of ideas has a

chance to be useless. So, brief.

R.F.Mager (1962, p.53) considers that a performance objectives must contain: an observable

behaviour, the description of the important conditions under which the behaviour is expected to occur,

and how accurate the performance must be.

R.F.Gagné (1965, p.34) breaks the statement of an objective into four basic components: the

stimulus situation which initiates the performance, the observable behaviour, the object acted upon and

the characteristics of the performance that determine its correctness. Performance objectives then ae

described in a concrete manner/ terms.

De Landsheere (1979, p.203) believes that "formulating a complete operational objective

comprises five specific directions: who will produce the desired behaviour, observable behaviour that will

prove that the objective is achieved, which will be the product of this behaviour (performance) under

what conditions must occur behaviour on the basis of which criteria we conclude that the product is

satisfactory". It easily finds similarities of these representative viewpoints. And yet, these components,

either three or five, have weaknesses that this paper will surprise during the subsequent development of

ideas.

Goals (learning intentions) specific to each lesson should be a combination of surface, depth and

conceptual learning; they can be on short term (for a lesson or part of the lesson) or on long term (for a

series of lessons). When these goals are clear for students, enabling them to anticipate the necessary steps

success, they become functional (Hattie, 2014).

When?”

The predict answer: "At the end of the lesson" is a component of the objective. Probably many

theorists and practitioners will consider unnecessary this statement, considering that this location time is

implicit. Moreover, the writing of this segment for each statement / objective can be characterized even as

energetic-consuming act.

However, the continuous updating of this milestone is very useful because it invites teachers, in

their role as designers of school learning, use psychological and pedagogical valid criteria. First, it is

necessary that the entire set of operational objectives to be preceded by this formula: "At the end of the

lesson." Secondly, it is important that the teacher-designer to be aware what this "end of the lesson."

Previous ideas should have effects on the understanding component "When?" the objective. When

will formulate the objective, it must be time bound. In other words, the performing presumed by the

objective must be achieved on the basis of both learning experiences: in the classroom and at home. At

the technical level of operational, together with the need to specify the landmark "at the end of the

lesson," it configures an important consequence: the aim will specify the behaviour performative

purchased not only from experience in the classroom, but also on the basis of the home learning

experiences.

Changing the perspective from SMART attributes set, the teacher-designer guarantees the T (Time

/ Timely / Time Bound). Second, they will reflect and attribute level Achievable / Attainable.

Who?”

The predict answer: "The students". Naturally this component of the objective is easy to predict,

too. But what does it mean to be in terms of pedagogical logic? First, the "students" can means "all

students". But can be performed the same desirable behaviours (in its quality of school learning product)

by all students in a class at the same level of complexity and difficulty? If not, must recognize the

following fact: the objective specify a purchase achievable only by some students. Not by the all.

If the answer is affirmative, must recognize another reality: the teacher sets the challenges on the

minimum difficulty and complexity level, an entire non-pedagogical decision: what about the students

with higher learning tools. It outlines thus a problem: how to ensure conditions Achievable / Attainable

and Realistic?

A possible solution is compliance with one of the fundamental principles of differentiation and

individualization instruction (Petre, 2013): every teacher-designer will formulate different levels of the

performance or will formulate different types of behaviours performative adapted to levels of class’

student (usually, a teacher identifies three levels: good students, average students, weak students). This

idea is formulated, in a way, by Negreț-Dobridor (2005).

But this strategy will be detailed at "the performance’ level" component. In conclusion, the

segment "the students" should be understood in a realistic way. Technically, the teacher will formulate

objectives so as to provide visibility of purchases that each student must achieve. Therefore, in the

content of an operational objective must be specified "each student" (ibidem, 2005).

What?”

The predict answer: "the behaviour". Although it seems the most "transparent" part of an

operational objective reality is not. Naturally, "for all practical behaviour, in this case the action,

translates into a verb to be chosen carefully. (...) We must avoid intellectualist verbs and verbs that

express behaviours to choose concrete, observable" (De Landsheere 1979, p.206). These ideas are useful

and criticisable, too, because they seem to give importance exclusive to observed behaviours, ignoring the

unobserved ones: "The objectives of cognitive and affective features include thinking and sensitivity that

are not directly observable" (Kibler et al., 1970, in De Landsheere, 1979, p.205). True, but the teacher

must anticipate these events and to accept the challenge to surprise them as purchases of pupils, so to

anticipates them in objective content.

It is important to note a condition: the verbal formula which is called the desirable behaviour must

be concrete, a non-intellectualist one. Thus, the desirable behaviour (performing) can be easily observed

and evaluated. This condition ensures the M (Measurable) attribute.

One detail: must be encouraged the formative dimension of learning. Learning outcomes are

formulated in syllabus/ curriculum in terms of competencies. Therefore, the set of the specific operational

objectives of a lesson must contain competences’ derived components. There is no the context to drill this

process. In short, the set objectives of a lesson must specify the type behaviours as: knowledges, attitudes,

attitudes.

Do not forget: at the level of a lesson is formulated the operational objectives type, therefore, the

knowledge, abilities and attitudes that are targeted must be derived at an operational level. At the specific

level it remain generally formulated, which would impede their realization.

Exemplification. The specific competence: Respecting the personal hygiene rules. Syllabus for 2nd

grade

At le specific level, can be derived components as:

a. Knowledges: a1. Knowing the personal hygiene dimensions/ a2. Knowing the tools for/ of

personal hygiene/ a3. Knowing how to use the tools for/ of personal hygiene/ a4. Knowing a set of

personal hygiene rules

b. Abilities: b1. Correct using of tools for personal hygiene

c. Attitudes: c1. Collaborating with parents for respecting the personal hygiene rules/ c2.

Manifesting initiative for respecting the personal hygiene rules.

Of course, it can be formulating other expectation, too. Important is to be aware at the general

level of these statements. So, they cannot be the aims of a lesson. They cannot be objectives. For the

lesson’s level we need a new derivation. This leads to the syllabus competencies’ operational

components. This means identifying concrete, operational landmarks, for each specific statement from the

list above.

The statement a1. Knowing the personal hygiene dimensions (a specific knowledge) may

generates the following operational knowledge: Knowing about five dimensions of personal hygiene:

corporal hygiene, food hygiene, life’s and work’s space hygiene, clothing hygiene, daily schedule

hygiene.

From this "point" it can start the formulating the knowledge performs at a desirable level,

operational one. For example, "to list the five dimensions of personal hygiene." At a higher level of

complexity and difficulty can be formulated the performing "formulate statements on the content of each

dimension of personal hygiene." More analytical: "to make statements on the content of bodily hygiene /

natural" or "to make statements on the content of food hygiene", etc. If these knowledge objectives are

considered by the teacher not relevant enough, then he can check the set of operational knowledge

derived from other knowledge existing at specific level.

The statement b1. Correct using of tools for personal hygiene (a specific ability) may generates the

following operational abilities: ”a correct using of tools specific for each personal hygiene dimension

(corporal hygiene, food hygiene, life’s and work’s space hygiene, clothing hygiene, daily schedule

hygiene)”. Or, more analytic: ”to use correct the tools for corporal hygiene”, ”to use correct the tools for

food hygiene”, etc.

The statement c1. Collaborating with parents for respecting the personal hygiene rules (a specific

attitude). This represents a serious challenge to the operational approach. In fact, this was one of the most

serious weaknesses associated to operationalization approach: impotence in the face of type attitude

expectations. Considered time-consuming acquisitions, it is believed that attitudes cannot be associated

with lesson’s learning experiences. However, pedagogical challenge for the teacher is to be able to shape

attitudes indicators that they consider desirable, and this approach is one of operationalization.

The challenge, in this example, is to establish several indicators for collaboration, and based on

this approach, to formulate some expectations by objectives. We used the concept of "indicators"

because, in their capacity as "observable and measurable signs" (Chelcea 2004, p.137) are designed to

capture the attributes of a unit / realities. It outlines an exciting event: the teacher really is a scientist who

must solve the kinetic senses provided by nominal and operational definitions.

Thus, at the operational level, it decides what is most relevant behaviours of students; for example,

"to communicate daily with parent / parents to determine the menu" or "to decide with parent / parents at

the end of the week, the program of activities for the coming week", etc.

All those performing of operational level, regardless of their nature (knowledge, skill, attitude)

will be introduced into the operational objectives’ ”body”. Based on operational technique will become

components of operational objectives. The reflexive attitude of teacher will guarantee the desirable

performs. He will decide whether to opt for more knowledge or for more abilities type performing

behaviour. But it must not ignore the principle of formative school learning experiences. This will ensure

attribute S (Specific / Significant). A last idea: The verb can be putted on future! In this way, the

objective express very clear the predictive nature of statement.

How?”

Predictive answer "the conditions". Another component of the operational objective, often reduced

to the significance of conditions for acquired behaviour manifestation. A wrong meaning, in pedagogical

terms, it lays the purchase in relation to a temporal landmark insignificant for process itself: after

project’s realization.

In other words, when specifies the conditions for manifestation of the behaviour-performing, it

assumes that it has already been formed. In this way, the objective no longer has its essential function, to

adjust/ to regulate learning, but fulfils a function attractive, but perverse, regulating the evaluation. By

mentioning this kind of condition, the teacher ensure manifestation of a negative influences of assessment

on learning: back-wash effect.

Moreover, such a condition specifying compromise condition of flexibility, adaptability,

functionality that must having the acquired behaviour. If performing must be proven in a default

condition, what arguments can be brought that that behaviour will manifest itself in various other

conditions?

Or that it might be usefully for the student in other situation or it can be accessed in other

circumstances. If required a child to identify the domesticated animals by circling the corresponding

figures which are on a page, it confirms the evaluative role of the request, on the one hand, and kept

insecurity that in another context, the child will recognize these animals, on the other side. In this way,

another condition-attribute is contradicted: S (Significant) or R (Relevant). The objective must be an

important purchase behaviour, useful for the economy of his future knowledge tools. Component

"condition" must be understood in another way: genetically, of specify the learning experiences through

that students form their expected behaviours. In other words, in the contents of an operational objective,

the teacher must anticipate not only the behaviour that must form (expressed by the verb, of course), but

also a set of learning experiences upon which this behaviour occurs. In a genetic way, the conditions must

show what are the learning experiences that produce the desirable performing behaviour?

An important detail: learning experiences can be both in the classroom and at home (homework).

So, these conditions can include: views of videos thematic, heuristic conversation, text analysis,

observations, conversations in work-group, independent study materials, discoveries...Such details allow

a good anticipatory visibility for learning experiences of students, and ensures landmarks regulating these

experiences.

How much?”

The predictive answer: "the level of performance". Professor skills are very important in determining

what level of the performance is desirable. In terms of quality or/ and quantity. Not all students can

perform at the same level, so it is essential that the teacher expected to adapt the expected performing

behavior to different levels existing in class. This provides a healthy differentiation in terms

psychological and pedagogical. Is managing the dynamic individualization - differentiation. According to

Hattie (2014, pp.101-102), "effective teachers successfully plan a lesson by choosing objectives that are

sufficiently stimulating and by organizing learning situations that will help students achieve these goals." In the meta-analysis conducted on the impact of exercising, Marzano (2015, p.107) presents the results of

studies made by Bloom (1976), Feltz and Landers (1983), Ross (1988), Kumar (1991). The average effect

size is between 0.48 and 1.47 and progress percentile is between 18 and 44.

Conclusions

It is necessary to mention some of the consequences of such an approach. Specifying all the

components of an operational target provides consistency to the effort of learning design. Teachers must

accept that the wording of a statement as operational objective cannot ignore any parts. Then it is

important that each component be appropriate understood, in a psycho-pedagogical way. The essential

role of operational objectives is to regulate learning, so their components cannot be built with an eye on

evaluation. Evaluation relates to the performing behaviour specified in goal, is truth, but assessment tasks

are not the learning tasks. The learning tasks are just learning experiences. And these are condition for a

new performing behaviour. This function of learning regulate is accompanied by another: to give a clear

advanced image on those purchases that the teacher believes as relevant. In this context, conceptualization

and operationalization actions are essential. They allow the passage from the general level of goals

(specific competencies) at the concrete level, of the lesson’s objectives. It is also important that the

operationalization not be limited only to knowledge behaviour. Of course, depending the content of

school object, the challenges for operationalization are different, but the principles are the same. Finally,

an operationalized objective as example: At the lesson’s end, basis on PPT presentation, the tasks group

resolving, but even on independent home study, each student/ pupil will list five activities for a balanced

daily schedule.

References

- Ågerfalk, P.J. (2004). Grounding through operationalization –constructing tangible theory in is research.

- 12th European Conference on Information Systems. Retrieved from

- http://www.vits.org/publikationer/dokument/425.pdf

- Ambrose S.A., Bridges M.W., Lovett, M.C, DiPietro, M. &Norman, M.K. (2010). How learning works. 7

- research-based principles for smart teaching, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Babbie, E. (2010). The practice of social research, Iasi: Polirom Bloom, B.S. (ed.) (1981). Taxonomy of educational objectives. Cognitive domain, (24th Edition), New York: Longman Bloom, B.S., Madaus, G.F. & Hastings, J.T. (1981). Evaluation to improve learning, McGraw-Hill Book Company Chelcea, S. (2004). Methodology of sociological research. Quantitative and qualitative methods, Bucuresti: Economică De Landsheere, V. & De Landsheere, G. (1979). Defining the objectives of education, Bucuresti: EDP Gagné, R.M. (1965). The analysis of instructional objectives for the design of instruction. In R. Glaser (Ed.). Teaching machines and programmed learning. Data and directions. Washington DC: National Education Association Harden, M.R. (2002). Learning outcomes and instructional objectives: is there a difference? In Medical Teacher, 24(2), 151–155 Hattie, J. (2014). Visible learning for teachers, Bucuresti: Trei 1330

- Hattie, J. & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. In Review of Educational Research, 77 (1),

- 81-112

- Lee, W. & Reeve, J. (2013). Self-determined, but not non-self-determined, motivation predicts actions in

- the anterior insular cortex: An fMRI study of personal agency. In SCAN, 8, 538-545 Mager, R.F. (1962). Preparing instructional objectives, Palo Alto: Fearon Martin, R., Cohen, J.W & Champion, D.R. (2013). Conceptualization, Operationalization, Construct Validity, and Truth in Advertising in Criminological Research. In Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Criminology, 5 (1), 1-38 Marzano, R.J. (2015). The art and the science of teaching, Bucuresti: Trei McLeod, G. (2003). Learning Theory and Instructional Design. In Learning Matters, 2(1). Retrieved from http://principals.in/uploads/pdf/Instructional_Strategie/learningtheory.pdf Merriam, S. B. & Caffarella, R. S. (1999). Learning in Adulthood: A Comprehensive Guide. (2nd Edition). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Negreț-Dobridor, I. (2005). Didactica nova, București: Aramis Petre, C. (2013). About school instruction. Nothing important. Craiova: Sitech Petre, C. (2014). About lesson. A chat model. In Public Responsibility in Education, Constanța: Crizon, 155-159 Petre, C. (2015). The lesson – experience of school learning. A possible pedagogical interpretative model.

- In Education from the perspective of values. Tom VIII: Suma paedagogica (pp.205-209), Bucuresti: Eikon Saul, C., Hofmann, P., Lucht, M. & Pharow, P. (2011). Competency-based approach to support learning objectives in learning, education and training. In Rohland, H. (Ed.) Gesellschaft für Informatik -GI, Fachgruppe E-Learning: DeLFI . Retrieved from http://subs.emis.de/LNI/Proceedings/Proceedings188/21.pdf Yamanaka, A. & Wu, L. Y. (2014). Rethinking Trends in Instructional Objectives: Exploring the Alignment of Objectives with Activities and Assessment in Higher Education – A Case Study. In Instruction, 7(2), 75-88. Retrieved from http://www.e-International Journal of iji.net/dosyalar/iji_2014_2_6.pdf

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Petre, C. (2017). The Operationalization of Learning Objectives. An Alternative Interpretative Scenario. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 807-817). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.98