Abstract

This research focuses on initial literacy. We conceive reading as a complex cognitive process that involves many skills; it does not only include the capacity of decoding letters but also the ability of selecting, understanding and interpreting a text critically and taking into consideration pragmatic factors. Our study is based on literature about reading acquisition in early childhood and Frith's description (

Keywords: Early literacyresearch methodologies in educationlogographic phasereading skills

Introduction

Considering reading a complex cognitive process that involves many skills and that cannot be only reduced to the capacity of decoding letters but also to the ability of selecting, understanding and interpreting a text critically and taking into consideration pragmatic factors (Solé, 2010: 1), we introduce a research focused on initial literacy. Our study is based on literature about reading acquisition in early childhood (Ninio & Snow, 1986; Nodelman, 1988; Lewis, 2001) and the description of the steps that the child follows when they learn to read: the logographic, the alphabetic and the grammatical phase, described by Frith (1985). In previous researches we realised that there are lots of abilities required before children enter the logographic phase. In order to study this previous stage of written language acquisition, we have been observing, recording and analysing two-year old children interacting with books and we have designed a specific methodology for this purpose. In the following pages, we introduce the results of research: on the one hand, the description of the reading skills that a child acquires in its first contact with books and literature. These are described in sequenced stages from a constructivist perspective: therefore it is a descriptive approach, not prescriptive. On the other hand, we also describe accurately the methodology we have designed, so that it can be used by future teachers as a strategy to learn from practice and to develop their first field researches, since we consider that innovative educators have to be also researchers.

Theoretical Foundation

Learning to read is a long process since it does not involve only the acquisition of linguistic skills. This process includes the capacity of decoding (relate each letter with its sound) but also the ability of giving sense to texts taking into account graphic, contextual and pragmatic evidences.

Frith (1985) and Fons (2000) describe the process of literacy acquisition in three phases:

Frith conceives these stages as reading strategies too, and although they are learnt sequentially, expert readers domain all of them and could use the previous ones in specific situations: "The aforementioned three strategies are hypothesised to follow each other in strict sequential order. Each new strategy is assumed to "capitalise" on the earlier ones." (Frith, 1985: 307)

Picturebooks initiate children in visual, linguistic and literacy acquisition from early ages on, though there is insufficient investigation done, especially regarding cognitive processes in the first years of life. There are strong evidences that one to five-year-old children who read picturebooks (with the help of adults or coreaders) improve their vocabulary and their understanding of symbolic languages (pointing-naming game), as well as the improvement of conversational and narrative skills through dialogic reading -conceived as a democratic discussion of texts, a cooperative and critical reading strategy. As Kümmerling-Meibauer & Meibauer (2013) point out, most research on picturebook reading and literacy acquisition is approached by joint reading situations. These investigations establish connections between early reading practice and later literacy learning outcomes. The specific verbal interaction seems to be strongly related to later skills in reading and writing. Results stress out that children, who since early ages had frequent contact with picturebooks have acquired language competences and have less difficulties in reading and writing acquisition in later stages than those who have not or barely have read (Kümmerling-Meibauer, 2012). They are also more used to the symbolic significance of literature and are introduced to meta-linguistic and meta-literary phenomena. These learning processes start previous to the orthographic stage, since children are interested in books, symbols and stories long time before they show interest for letters. Therefore children could start their literacy acquisition in a subtle but fundamental way very soon. Our research focuses on these first stages and describes how children acquire their first reading skills.

Author's Contribution on the Existing Theory

A new Methodology for a New Research in Early Literacy

This research is set up in a context of constructivist education, using active and participative methodologies. The aim of researchers (and also of the school where the investigation was carried out) is that pupils are conductors of their learning processes that they learn through experimentation and exchange, mostly in moments they themselves decide. Consequently knowledge, understood as vast, debatable and constantly evolving, is constructed in collaboration and interaction of all education agents (teachers, families, children…), and stimulating materials and it is therefore to be seen as a collective and solidarity phenomenon. We should understand this research as a way to coach knowledge construction from an initial improvised and casual contact to a more rational and coherent one.

Having this theoretical framework into account, the role of the researcher is to observe and analyse how children interact with books and try to find out what they learn from these first reading activities. It is not easy, since children from one to five years -the age group we focused this research on- are also learning to talk and to move; reading is thus one of the many communicative skills they are developing. Therefore, the researcher will have to be able to detect different kinds of evidences: verbal evidences -what children explain or ask about the book they are reading-, but also postural evidences, gestures and facial expressions: how do they manipulate books, what images they are pointing at, what do they find disappointing or uninteresting and leave apart, etc.

It is very important to develop the research in a rich context, with a great variety of books and picturebooks that would stimulate children to explore them and consequently allow them to take their first steps in literacy. So, the creation of an alphabetizing atmosphere is an important requisite that can involve researchers, teachers and children.

The way we record and analyse the data obtained from practical reading experiences is inspired in clinical didactic methodologies (Rickenmann, 2006). This research methodology -based on Habermas theories- conceives education as a communicative phenomenon and focus on the analysis of interactions, but not only verbal ones: Vernant (2004:88, quoted by Sensevy, 2007: 7) underlines that there are

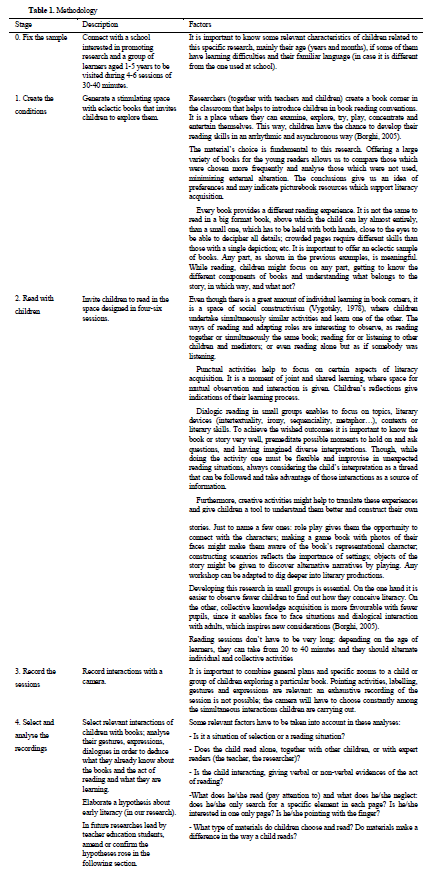

These are the steps followed in our research:

First Results for Further Investigations

Our main hypothesis is that children acquire lot of relevant competences related to reading (and writing) before they really start decoding letters, words and sentences. We will describe these skills grouping them in three categories, which are developed concurrently: Mechanical skills: Children discover the books as a singular object (or toy) of joy that enables them to enter other worlds; they learn to distinguish it among many other objects, they identify its characteristics and how to use it (and how it should not be used): a book is meant to be looked at, it cannot be squeezed or bitten, sit on or be thrown away. In higher steps, children find out that books have a front and back, an upper and lower part, and they must be held in a certain direction; pages are to be turned one at a time and they have a specific order and a reading direction. After many reading experiences, children will also realise that each page has to be understood as a conceptual space, one must be able to differ one page from a double-page spread, and usually read them sequentially.

sounds, on two dimensional surfaces, often painted in simple forms, colours and shades, and (specially in the first books) detached from any background, as floating in space.

By analysing relevant pieces of the recordings, we are able to detect which skills the child is acquiring and in what grade. These analyses give the teacher information about how to keep stimulating children to manipulate books, understand their symbols and to be able to understand and enjoy stories with each time more complex plots (both visual and verbal stories; with the help of an adult and autonomously). These are some examples of analysis of videos that support our theory, among many others.

Acquiring mechanical skills:

This girl is learning how to hold and handle books. Since she follows the teacher’s procedures, she opens the book so that it can be watched by others although she wants to read it by her own. She will have to learn that the posture we adopt while reading depends on partners and changes if we read individually, in little groups or for others.

Acquiring symbolic skills:

book.

Another example shows a reading situation where a girl interprets the book’s blank spaces as snow, and starts searching for it in each page: “Look here, there is also snow!” -she says. “And here too”, she repeats in the following page. Thus, she makes a hypothesis of the symbolic meaning of the white that does not work in most of the cases. Blank spaces do not always have a specific meaning, in some picturebooks they are only used as background. The girl seems to be interested in one single element probably because she is not used to look at complex images like these ones.

Acquiring narrative skills:

Another piece of recording shows children rereading a book which the teacher has often read to them. Although they are not able to read the letters, they are aware that the book contains a specific story. They are trying to remember what happened in each sequence with the help of the images.

These analyses would help teachers and future teachers realise that toddlers and young children are making great efforts to understand the act of book handling and interpretation. Many assumptions are built and rejected constantly in a very rich and complex cognitive reading activity, although letters are not necessarily involved in it. All these cognitive learning processes have to be studied deeply.

Conclusions

Our contribution describes the results of this research about early literacy and offers an effective methodology to develop further investigations in this field that can be applied by teacher education students, since we believe future teachers must also acquire research techniques. It is very important to stimulate the students to develop their ability to observe, analyse and take up a critical dialogue with themselves -what they think and what they do- and what surrounds them (Barnett, 1992); a dialogue that

allows them boost their learning process. So, despite giving students only certainties -specific knowledge edited by the professor and the academic institution-, we believe it is very important to give them strategies to build new knowledge from practical experiences that would be useful for them as professionals. These tools are based on observation, data collection and reflection.

On the other hand, studies of early literacy are a new field of research where evidences are eclectic, rich and yet uncertain (since children are learning to express themselves, hypothesis about how they read and what they know about books and reading can not only be based on their verbal outputs). Our description of the skills acquired in these first stages can help teachers and future teachers to interpret the interactions of little children with books and coreaders and develop further investigations about this issue.

Acknowledgments

This paper has received a support (as consolidated research group GREPAI-003 UdG) to improve

the scientific productivity of University of Girona 2016-2018 (MPCUdG2016).

Our special thanks to Casa Nostra School (Banyoles, Catalonia) for letting us developing reading

activities for their two-year old pupils and recording them.

References

- Barnett, R. (1992). Improving Higher Education. Buckingham: SRHE/Open University Press.

- Borghi, B. (2005). Los talleres en educación infantil. Espacios de crecimiento. Barcelona: Graó. Fons, Montserrat (2000). Aprender a leer y a escribir. Bigas, M.; Correig, M. (ed.). Didáctica de la en la educación infantil. Madrid: Síntesis.

- Frith, U. (1985). Beneath the Surface of Development Dyslexia. Patterson, K.; Marshall, J., Coltheart, M.

- (ed.) Surface Dyslexia, Neuropsychological and Cognitive Studies of Phonological Reading. London: Erlbaum.

- Kümmerling-Meibauer, B. (2012). Erste Bilder, erste Begriffe: Weltwissen für Kleinkinder.Leseforum Schweiz, Nr. 1. 2012. URL:http://www.leseforum.ch/kuemmerling_2012_1.cfm Kümmerling-Meibauer, B. & Meibauer, J. (2013). Towards a cognitive Theory of Picturebooks.

- International Research of Children’s Literature, vol. 6, issu. 2, Edinburgh University Press, 143-160.

- Lewis, D. (2001). Reading Contemporary Picturebooks: Picturing Text. London: Routledge/Falmer Nodelman, P. (1988), Words about pictures. The Narrative Art of Children’s Picture Books, Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press Rickenmann, R. (2006). Metodologías clínicas de investigación en didácticas y formación del profesorado: un estudio de los dispositivos de formación en alternancia. Actas del Congreso Internacional de Investigación, Educación y Formación Docente. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia. URL:http://www.unige.ch/fapse/clidi/textos/Clinica-did%E1ctica-RR.pdf Sensevy, G. (2007). Categorías para describir y comprender la acción didáctica. Sensevy, G.; Mercier, A.

- Agir ensemble: l’action didactique conjointe du professeur et des élèves. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Snow, C. E., & Ninio, A. (1986). The contracts of literacy: What children learn from learning to read books. W. H. Teale & E. Sulzby (Eds.), Emergent literacy: Writing and reading. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

- Solé, I. (2010). Ocho preguntas en torno a la lectura y ocho respuestas no tan evidentes. En Ministerio de Educación. Secretaria de Estado de Educación y Formación Profesional (ed.), Leer para aprender. Leer en la era digital, 17-24.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Juanola, M. M., Kunde, K., & Isern, M. F. (2017). How Do Children Read Before Being Able To Read? Tools For Research. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 705-712). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.86