Abstract

Life and work in the 21st century demand specific skills from students in order to be successful. It is the school’s and the teachers’ responsibility to prepare all children for the educational demands of life and work, in a rapidly changing world, by equipping the students with the required skills. This study focuses on four skills: creativity, critical thinking, communication and collaboration, which are part of the 21st Century Skills. If teachers are expected to enable the students to use such ways of working and thinking in the 21st century, then teacher preparation programs should offer multiple opportunities for teacher candidates to learn, develop and practice these skills. The article reveals ways of integrating the four mentioned skills during a Theory and Methodology of Instruction course, provided within a pre-service university study program for pre-primary and primary school teachers. The teacher candidates experienced training situations associated with each skill, and then, they were challenged to design such learning situations themselves, within an environment provided by interaction with peers. The teacher candidates’ perceptions of their teaching and learning activity related to the four skills are analyzed.

Keywords: 21st century skillscommunicationcritical thinkingcollaborationcreativityteacher preparation programs

1.Introduction

Education in the 21st century is profoundly affected by changes in society: globalization,

technology, labor market dynamics, immigration etc. Educational systems around the world are looking

for best practices to prepare children and young people in schools today to cope with the life and work

increasingly complex requirements of the 21st century. The life and work styles of the 21st century

demand a certain skills set from students. It is the school’s and the teachers’ responsibility to prepare all

children for the educational demands of life and work, in a rapidly changing world, by equipping them,

the students, with the required skills. Because teachers are expected to empower the students with such

skills, teacher preparation programs should offer multiple opportunities for teacher candidates to learn,

develop and practice these skills, named 21st Century Skills.

2.Paper Theoretical Foundation and Related Literature

International research, education planners, organizations interested in the education field - all

contributed to the development of the concept “21st Century Skills” and of the frameworks needed for

students to be successful in an information-based, technology driven, global society. For example, the

Partnership for 21st Century Skills (2010), which is an organization established in 2002 by leaders in

business and education, all advocating to assure a 21st century education for all learners, defined 21st

century students outcomes as the blending of core subject areas (traditional subjects taught in schools)

and 21st century interdisciplinary themes (global awareness, civic literacy, health literacy, financial,

economic, business and entrepreneurial literacy, civic, health, environmental literacy) with specific skills,

expertise, and literacy skills necessary for future success. Skill categories include: learning and

innovation; information, media and technology; life and career. Learning and innovation skills are

comprised of the 4 Cs of critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and creativity. Information,

media, and technology include literacy skills within each component (access and evaluate information,

use information accurately and creative, analyze media, create media product, apply technology

effectively). Life and career skills involve developing the ability to adapt to change, to be flexible, self-

directed, to manage goals and time, to work independently, to interact effectively with others, to be a

leader and to act responsibly (Partnership for 21st Century Skills, 2010, Appendix B).

In Europe, the 21st century skills have mainly been defined according to the European Reference

Framework of Key Competences, which was defined in the Recommendation on key competences for

lifelong learning (European Parliament, Council of the European Union, 2006, Annex). The

Recommendation defines 8 key competences needed by all individuals for personal fulfillment and

development, active citizenship, social inclusion and employment: communication in the mother tongue;

communication in foreign languages; mathematical competence and basic competences in science and

technology; digital competence; learning to learn; social and civic competences; sense of initiative and

entrepreneurship; and cultural awareness and expression (European Parliament, Council of the European

Union, 2006, Annex). In Romania these competences “determine the student's training profile for primary

and secondary education” (National Education Law, 2011, article 68, p.11). These key competences are

not finite and their development “should be supported by transversal capabilities and skills such as critical

thinking, creativity, sense of initiative, problem solving, risk assessment, decision-making and

constructive management of feelings” (Gordon et al., 2009, p.26).

Since teachers must be able to guide pupils towards skills needed in future society, the 21st

century skills, then teacher preparation programs should consider this issue, at different levels: standards,

curriculum, instruction and assessment. Teachers themselves need to acquire competencies to teach 21st

Century Skills to their students, to purposefully integrate these skills into the core curriculum.

From the perspective of initial teacher training, preparing students with these skills requires

creating learning practices and supports for prospective teachers, who have to learn new pedagogies with

curriculum and instruction that promote 21st century skills. In a study about the ways the adult pre-

service teachers apply 21st century skills in the practice, is considered that “is extremely important that

graduating teachers have such professional abilities as to implement 21st CS in their work skillfully and

with courage” (Valli, Perkkilä, & Valli, 2014, p. 122).

Considering that this research study is focused on fostering the skills from the Learning and

Innovation category, we are going to present them as they are defined in the Partnership for 21st Century

Skills (2009, p. 3-4):

• Collaboration skills involve the ability to work effectively and respectfully within a team, the

willingness to compromise to accomplish a goal, and assume shared responsibility.

• Communication skills entail being able to articulate ideas and thoughts effectively through oral,

written, and nonverbal methods, possess the ability to decipher meaning through listening, using

communication for a range of purposes and being able to converse in diverse environments.

• Creativity skills refer to using a wide range of idea creation techniques, such as brainstorming,

creating new and worthwhile ideas, being able to analyze and evaluate original ideas and working

creatively with others.

• Critical-thinking skills are about using various forms of reason, such as inductive and deductive,

analyzing how parts of a whole interact with each other, evaluating major points of view, and reflecting

critically on learning experiences and processes.

Learning and innovation skills “are being recognized as those that separate students who are

prepared for the more and more complex life and work environment of the 21st century, and those who

are not” (The Partnership for 21st Century Skills, 2009, p.3). We mention that all four skills are also

found in the competencies profile of the European citizen for the 21st century.

3.Methodology

The subjects of this research study included 22 students (all female) enrolled in a three years

undergraduate study program for training pre-primary and primary school teachers, named Pedagogy of

Primary and Preschool Education, at Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, during the first semester of the

2015-2016 academic year. These students attended the discipline of Theory and Methodology of

Instruction (TMI), which is part of the teacher training curriculum for pre-primary and primary school

teachers, with 2 hours of course activities and 2 hours of seminar per week. The aim of this course is to

help students to acquire skills in the design, implementation and evaluation of training at preschool and

primary education levels. Our intentions related to this study were to provide the 2nd year students with

opportunities to acquire knowledge and practice of the 21st Century Skills within this discipline and to

prepare the transfer of teaching these skills on pre-primary and primary curriculum, considering the

perspective that these students are going to be future educators, who are expected to be able to facilitate

the acquisition of 21st century skills for their future pupils. The 21st Century Skills that were chosen as

the focus of this study were: communication, critical thinking, collaboration and creativity (the “Four

Cs”), which form the framework for classification. We would like to mention that these four skills are

compatible with the professional and transversal profile of competences for the graduate of this Bachelor

study program.

The goal of our investigation was to prepare the teaching candidates in order to own, teach and

assess the “Four Cs” in relation with the curriculum they will teach as pre-school and primary future

teachers. For this, we designed a two phases instructional model within the discipline. During the first

phase, the students had been exposed to a wide range of teaching and learning strategies during the

courses and seminars activities throughout the semester, including those that helped them become

familiar with the concept of 21st Century Skills. The students were explicitly taught how to perform the

“Four Cs”. Then, the students practiced these skills (communication, critical thinking, collaboration and

creativity) directly related to the discipline associated content. This phase was envisioned as a

background for developing a peer teaching process, from the perspective of these skills.

Convinced by the idea that having more practice before graduating has a crucial role in the

improvement of the practitioners’ professional skills, we provided an instructional environment for the

“Four Cs” teaching practice within the 2 hour seminars, starting with the 7th week of the semester (phase

2). This experience of micro-teaching practice was seen as a preparation for the prospective teachers’

authentic practice in kindergartens and schools. Considering the three dimensions of instructional design -

planning, instructing and assessing (Skowron, 2006), the prospective students were given support for

going through the following stages:

• Planning to teach at least one of the “Four Cs” skills – future teachers decided about the content

(extracted from the curriculum for preschool and primary school education) and skills to be taught, the

methods that will be used, and the assessment evidence that will be gathered. The students were offered

the opportunity to choose how to approach the task: individual or in groups (up to three members).

• Micro-teaching at least one of the “Four Cs” skills – prospective teachers used specific methods

to teach content during the assigned time (20-30 minutes).

• Assessing at least one of the “Four Cs” skills - using measures to determine whether the student

has achieved the established instructional outcomes.

The micro-teaching session was part of course examination, in addition to the written test and

students’ portfolios. The students had to conduct documentation work regarding the curriculum for

preschool and primary education, in terms of the four skills. They are treated as goals (for preschool) and

skills (for primary education), within experiential or curricular domains and contents. Students were

given the opportunity to choose the level (pre-school or primary), field / area, discipline, subject, type of

work, skill / s (one or more) to support the activities of micro-teaching, work form (individually or in

groups).

Thirteen sessions of micro-teaching took place: six individual sessions, five - in pairs and two in

groups of three. 62% of these micro-teaching sessions were focused on applying the “Four Cs” on themes

extracted from the curriculum for primary school (the disciplines that were covered: Romanian literature

and language, Mathematics, Natural Science, Personal Development, Visual arts and practical skills) and

38% were focused on pre-school curriculum (with the following domains covered: Language and

Communication, Aesthetic and creative, People and society, Sciences). The students’ choices covered all

four desired skills. Even more, over 50% of the micro-teaching sessions were focused on more than one

of the “Four Cs”.

Because the ability to teach in order to master content - while also developing 21st century skills

among students- proves to be a challenging task for most teacher candidates, they were given support and

feed-back in the planning work. At the end of each 21st century skills micro-teaching episode, time has

been allotted for reflection on content, skills and teaching process (completed by the peer who

participated to that session, by the instructor, the member of the teaching team). Through this model we

intended to provide the students with the opportunity to develop experiential knowledge of 21st Century

Skills - learning and teaching in a controlled way and getting feed-back after the micro-teaching activity,

in order to encourage reflection.

Through a qualitative design, the study explored teacher candidates’ experiences from the Theory

and Methodology of Instruction course. The following questions guided the investigation:

• To what extent do students believe that they have developed the desired “Four Cs” skills and the

ability to integrate these skills into pre-school and primary school curriculum?

• What aspects of the course influence students’ perception on development of the “Four Cs” skills?

What strategies do students deliberately use/intend to use to promote the “Four Cs”?

How did the students perceive their teaching and learning activity related to 21st century skills,

in terms of benefits and difficulties?

At the end of the semester an anonymous survey questionnaire was administered in order to obtain

students’ perceptions of various aspects of their teaching and learning activity related to the “Four Cs”.

The questionnaire contained closed and open-ended questions, which supplied data for analysis. The

questions in the questionnaire were designed around the research questions. Students’ open-ended

responses were used to understand the students’ perspective of 21st Century Skills. A coding process was

utilized in attempts to gain meaning from the data collected during the research study.

4.Results

In this section, the findings from the analysis of the student questionnaire are going to be reported.

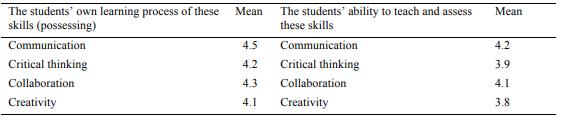

The first aspect of interest was the students’ perceptions on the “Four Cs”. Students were asked to rate the

extent up to which they developed the “Four Cs” within the course experience on a 5-point Likert- type

scale (1 = in a very small extent; 5 = In a very large extent). Each skill was considered from a double

perspective: the students’ own learning process of that skill (possessing) and the students’ ability to

integrate (teach and assess) that skills into pre-school and primary school curriculum, as a result of being

enrolled in the course. The ratings are shown graphically in Table 1.

The students rated each of “Four Cs” on a 5-point Likert-type scale, for both desired dimensions.

The findings support the idea that instructional practices implemented during the TMI course determined

the students’ positive perceptions on the opportunities to develop these four skills. The results, however,

show lower values for the component related to teaching and assessment of these skills for pupils,

compared to the size of the development of these skills (which received values of more than 4 on the

Likert scale). The students were faced with the reality that the transfer of these skills in a pedagogical

activity requires multiple and complex aspects such as: formulation of objectives, organization of content

and a good choice of training strategies, selection of the evaluation methods, classroom and time

management etc. and that more practice is necessary for developing these skills.

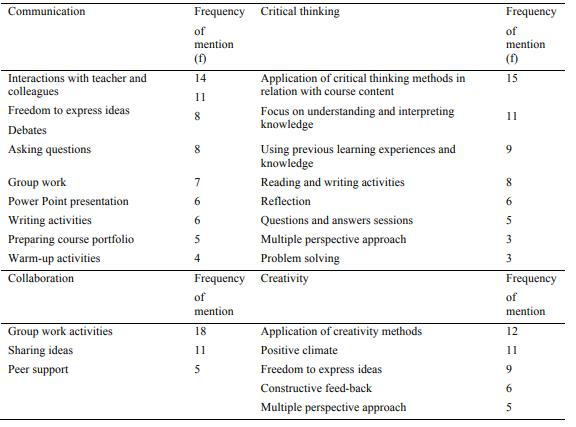

The next research questions aimed to identify what aspects of the course influenced the students’

perception on “Four Cs”, considering the same double perspective. Thus, for each skill (communication,

critical thinking, collaboration and creativity) two open-ended questions were formulated. The first one

targeted students' perception on the opportunities they had to develop that skill for themselves as a result

of being enrolled in the course, and the second focused on the students' perception of the opportunities

they had to teach and assess that skill. For both questions concerning each skill, students provided more

than one answer and the responses were grouped and categorized, as connecting themes emerged.

The most reported aspects of the course that helped students to possess the “Four Cs” skills are

presented in Table 2.

With respect to opportunities for development of ability to integrate (teach and assess) the “Four

Cs”, the students’ responses were quite similar for each skills. That is why we presented them together.

The aspects most frequently mentioned by the students were: micro-teaching sessions - planning and

delivering (f=17), taking part into micro-teaching sessions sustained by peers (f=14), feed-back from

teacher (f=13), feed-back from peers (f=11), self-reflection (f=8), learning by doing (f=8), learning from

others’ actions (f=7) mistakes (f=3).

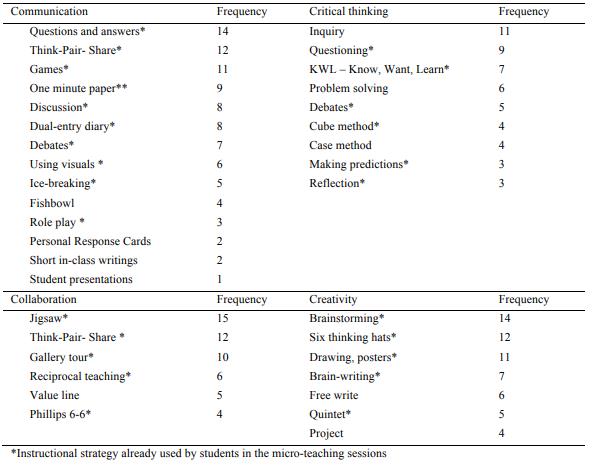

The third research question sought to understand students’ perspectives on the relationship

between the development of “Four Cs” and the instructional methods they used or they would use in their

teaching activities. Table 3 presents the students’ multiple responses to the question: What strategies do

you deliberately use/intend to use to promote the “Four Cs” skills?

Students' answers made reference to a wide range of instructional strategies that can be used for

the development of the "Four Cs", including those that have been applied in the work during the seminar

and their sessions of micro-teaching but also other strategies whose potential is worth exploring.

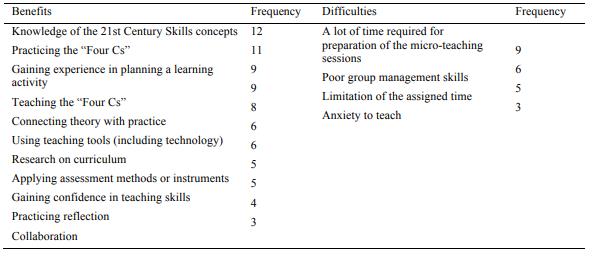

In the final part of the questionnaire, the participants were asked to list their own benefits and the

difficulties met in their teaching and learning activities related to 21st Century Skills. The benefits and

difficulties were coded into categories (see Table 4) and the results were listed according to frequency of

occurrence. Participants perceived the course as a worthwhile experience and its components as beneficial

in their development as teachers. Overall, positive students’ comments revealed that many students

enjoyed the course experience. Here are some students’ comments:

“This course gave us an excellent opportunity to practice the skills that first of all we need, as

future educators, in order to initiate the children with whom we work. The fact that we practiced here first

gave me confidence that I can do this in class too. Feed-back from the teacher and from classmates helped

me realize my strengths, but also aspects that need improvement, such as: timing and monitoring class

work." (Pre-service teacher 6)

“Great experience! I learned from what we did, what we discussed and what I've seen, from

mistakes, but also from the examples of good practices. I taught along with two other colleagues. We

have designed together, we divided the tasks and emotions and I was happy with what we managed to

do." (Pre-service teacher 11)

"I never thought that for such a short task (20 min) I have to work so much. All the preparation

work - to choose what I want to do, make a plan, to formulate goals, choosing methods to evaluate it-

took me much longer than I thought. It was the first sketch plan that I made and my first experience as a

teacher. I chose to work on the skill of collaboration, applying the Jigsaw method and I succeeded with

my peers' support. After the activity discussions were very helpful. I feel like I have a lot to learn, but I

am on the right path." (Pre-service teacher 14)

Although student-teachers did not mention motivation as a benefit, it was easily to observe that

manifesting in their creativity and efforts regarding the activities preparation. The chance to teach and to

act like a teacher, before becoming ones, was challenging for the students, but not overwhelming.

The difficulties the students encountered during the whole process are natural for the stage they

are in and can be overcome in the course of time as prospective teachers gain more experience (for

instance: anxiety to teach or group management skills). Besides these, we also observed that some of the

prospective teachers’ tended to stand in front of the classroom and not move around the classroom during

class teaching; some students had too much visual contact with instructional materials in detriment of

class eye contact, others paid more attention to the content than to the needs of the class. All these issues

were discussed during the reflection stage, offering constructive feedback to students.

5.Discussions

All students enrolled in the Theory and Methodology of Instruction course were offered the

opportunity to discover instructional strategies adequate for teaching at pre-school and primary school

levels and to connect these strategies with 21st Century Skills. Students gained experience in four skills:

communication, critical thinking, collaboration and creativity in terms of learning, practicing, teaching

and assessing them. For some students adopting the “Four Cs” was easier than for others, especially for

those with some experience in working as a teacher, but all the students proved dedication during the

formal activities.

Throughout the entire semester the goal was to create an instructional context in which these skills

to be known, practiced and integrated into the course associated curriculum; after that, the students tried

to realize the transfer of these skills to the pre-school and primary school curriculum. Thus students have

experienced training situations associated with each skill, and then, they designed and created such

learning situations themselves. We considered that the environment provided by interaction with peers is

a more suitable and less stressful one for students, in terms of teaching these skills. The approach we

developed offered students the opportunity to practice the teaching design process, to formulate concrete

education objectives and to track their realization by choosing appropriate content and methods, to

practice assessment from the teacher's perspective.

The option to let the students choose a theme, a skill, the practice methods, approach (individual or

team) had a motivational effect for them. The students had the chance to put into practice the instructional

methods covered within the course’s curriculum. During the micro-teaching sessions, many instructional

methods were applied by the students themselves, such as: role play, six thinking hats, brainstorming,

gallery tour, jigsaw, Think/Pair/Share, reciprocal teaching, games, predictions and so on. They also used

traditional and modern teaching aids, such as: blackboard, chalk, text books, charts, pictures, posters,

maps, atlases, worksheets, models, crossword puzzles, toys, costumes, computers, Power Point

presentations, overhead projector, DVD players, educational CDs and DVDs and so on in order to help in

effective teaching, to makes the micro-teaching activities more interesting and realistic and to make the

learning process more solid and durable.

From the perspective of the evaluation process that they had to make during their activity, the

students chose formative methods and tools, such as: observation, rubrics, five minutes essay, questions

and answers, drawings and so on. Teacher candidates received assessment feedback in order to reflect on

and to refine their own teaching activity. As new micro-teaching activities were planned and

implemented, the students reflected on the process and learned from each others experiences.

6.Conclusions

Within the provided student-centered instructional context, the prospective teachers had the

opportunity to begin practice for teaching the 21st Century Skills in an initial course on Theory and

Methodology of Instruction. They had the chance to develop, practice, teach and assess four skills:

communication, critical thinking, collaboration and creativity learning, which are part of the so-called

21st century skills. This was a preparatory experience for the real pedagogical practice in schools, where

prospective teachers could continue implementing what they started doing during this course.

The students acquired knowledge of the 21st Century Skills concepts and practiced the integration

of the “Four Cs” into the curriculum for pre-school and primary school education with their peers, as an

exercise for their professional future. They are the teachers of 21st century who are expected to have

expertise in teaching the 21st century skills to their students. The knowledge, the skills developed during

teacher education are crucial for how students will behave as future teachers, for how they will encourage

21st century skills. We are aware that the ability to bring the “4 C’s” to life and to guide pupils into

developing these skills requires a lot of pedagogical practice, reflection and continuing professional

development. By our approach these teacher candidates made a small step on a long and challenging way

to the future. Even though this study has its limitations as a result of the small sample population of 22

students, we hope that the findings may inspire other university teachers involved with teacher education

programs to ensure appropriate knowledge and experience related to the 21st century skills for pre-service

teachers. They need this for themselves and for their future children and pupils.

References

- European Parliament, Council of the European Union (2006) Recommendation of the European

- Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning.

- Brussels, Belgium: Official Journal of the European Union (2006/962/EC), OJ L 394, 30.12.2006, pp. 10–18. Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32006H0962&from=EN Gordon, J., Halasz, G., Krawczyk, M., Leney, T., Michel, A. Pepper, D. Putkiewicz, E. & Wisniewski, J.

- (2009). Key Competences in Europe: Opening doors for lifelong learners across the school curriculum and teacher education. Warsaw: Center for Social and Economic Research.

- Legea Educatiei Nationale [National Education Law]. Monitorul Oficial, 18, 10 ianuarie 2011. Retrieved from http://doctorat.ubbcluj.ro/documente/legi/Legea_educatiei_nationale_2011.pdf Partnership for 21st Century Skills (2009). P21 framework definitions. Retrieved from http://www.p21.org/storage/documents/P21_Framework_Definitions.pdf Partnership for 21st Century Skills. (2010). 21st Century Knowledge and Skills in Educator Preparation.

- Retrieved from http://www.p21. org/storage/documents/aacte_p21_whitepaper2010.pdf Skowron, J. (2006). Powerful lesson planning: Every teacher’s guide to effective instruction (2nd ed.).Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Valli, P., Perkkilä, P., & Valli, R. (2014). Adult pre-service teachers applying 21st century skills in the 1 (2), 115-129. Retrieved from practice. Athens Journal of Education, http://www.atiner.gr/journals/education/2014-1-2-2-Valli.pdf

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Cretu, D. (2017). Fostering 21st Century Skills For Future Teachers. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 672-681). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.82