Abstract

Inclusive education is one of the components of today’s education defined by its inter- and transdisciplinary features. Observing the implicit demand to train teachers for inclusive education in Romania, this study aims to raise awareness of this need and verify its intensity in teachers. The general hypothesis of the observational study states that as teachers climb the steps of the educational system, their need to prepare for inclusive education diminishes. The method used was the questionnaire-based inquiry. The questionnaire comprised 18 items with open and closed questions.The sample consisted of a total of 400 teachers, 100 for each of the 3 stages of the pre-university educational system (preschool, primary, middle education, respectively 50 from the urban and 50 from the rural environment in each category) and 50 teachers each from high-school and the university educational system. The recorded data and conclusions of the study could constitute an analysis of the needs for future research-development projects. They will allow the creation of inclusive education modules/programs in the university environment.

Keywords: Inclusive educationspecial educational needs of studentsdifferentiation pedagogy

1.Introduction - Inclusive Education – From Concept to Formative Challenge

The approach to children with special educational needs knows various specific policies and

strategies across countries. It has both a general determination, common to all countries, and a national

one (Florian&Rouse, 2009). It is related to the formative tradition, legal regulations, but also to the

awareness of the problem at the macrososcial level, the attitude of decision-makers towards it, the

availability of investments in this sector. Ultimately, it is about respecting children’s rights! The problem

is aggravated by serious problems of the contemporary world (poverty, food crisis, disease, migration,

racism, diversity, school drop-out). The philosophy under which teacher initial/continuous training is

conceived and achieved becomes, along with the financial allocation, crucial for ensuring inclusive

education (IE).

1.1.Inclusive Education – Conceptual Highlights and Open Issues

The research subordinated to the student-centred paradigm marked the formative practices of the

80s. The concern to find the best education for each child separately, in relation to his capabilities/needs

did not always produce the desired practical solutions. For example, the segregation of students based on

performance or health related criteria did not generate desirable results (Yadav &all, 2015). Not only did

it not yield the expected school performances, but also recorded relative failure in terms of the students’

integration in the micro/macro community. The key challenge of IE has remained that of harmonizing, in

the same class, a great diversity of school population, namely students who are extremely different in

many respects (including those with and without special educational needs), while the school usually

operates, almost permanently, with classifications and labelling (McIntyre, 2009). In this sense, IE, as an

expression of social inclusion (Florian&Rouse, 2009), involves identifying and eliminating possible

sources of exclusion (Bukvić, 2014). It designates the effort “of overcoming barriers that prevent the

participation and learning of all children, regardless of their race, gender, social background, sexuality,

disability or attainment in schools” (Bustos&all, 2012). The domain of IE has been increasingly outlined

and students with special educational needs found their place in this process. After Rafferty, Boettcher, &

Griffin (2001) IE is “the process of educating children with disabilities in the regular education

classrooms of their neighbourhood schools - the schools they would attend if they did not have a

disability - and providing them with the necessary services and support” (apud McCrimmon, 2015).

Following the major social transformation of 1989, in Romania IE has undergone a slow, sinuous,

but continuous development, as an expression of two fundamental causes: 1. an awareness and

recognition of the number of children with special educational needs; 2. the need to ensure equal rights to

education for all children, no matter their difficulties. The real physical, mental, emotional, and social

vulnerability of children with special educational needs makes them a distinct category of beneficiaries of

education, which is what engages the identification and usage of specific strategies for knowing and

approaching them in accordance with the identified needs. The restructuring of the Romanian traditional

school into a warm, friendly institution, an optimal environment to implement clear and coherent

inclusive policies that would produce the expected long term positive effects for an ulterior integration in

society, depends essentially on the teacher, as vital partner in IE (Vaillant, 2011).

1.2.Training Teachers for Inclusive Education – Context and Domestic Challenges

Beyond the prejudice that the integration of children with special educational needs in classes with

normally developed children “is a policy doomed to fail” (Jordan, Schwartz&McGhie-Richmond, 2009),

it remains a complex issue, with various, sometimes contradictory approaches/solutions (idem). López-

Torrijo&Mengual-Andrés (2015) show that the need to train teachers for IE has been supported since

1978. Despite growing concerns related to increasing the quality of education, teacher initial training for

IE for middle/high-school/university education is practically absent in Romania. The only qualified

people in the field are graduates of the Special Psycho-pedagogy program. In the official curriculum of

teacher initial training, for level I and level II, there is no separate discipline related to the issue of

students with special educational needs. And although the training of teachers for primary and preschool

education comprises such a component, it is deficient and limited to just 1 compulsory course (Basics of

Special Psycho-Pedagogy, also possibly The Psycho-pedagogy of children with learning difficulties),

with the possibility to supplement it with an optional course (Logopedia). Thus, the reality of our

educational system is similar to that of other countries in the region (e.g. Turkey, Serbia) (Sazak Pinar,

2014; Jovanovic&Rajović, 2013). Hence, it is no wonder that the attitude of teachers towards such

educational contexts is one of reticence, to say the least, and their work is burdened by serious concerns

that exist in most educational systems: a misunderstanding of the role of the teacher in an inclusive

classroom; the fear that teachers could not pay due attention to students without special needs; the fear

that they are not methodologically prepared to work with such students (Jordan, Schwartz&McGhie-

Richmond, 2009).

2.Research Methodology

The ascertaining study aims to complete a research on identifying a real need of teachers for IE

training, clearly outlined and of the same intensity across the entire course of the Romanian educational

system (preschool, primary, middle, high-school, university education), a basis for future formative steps

in the field.

levels – and university education)?

is stronger than that of teachers in higher education;

is manifested mostly in primary education;

is manifested mostly in the urban rather than rural areas.

The research was conducted during the 2015-2016 academic year, on a sample of 400 teachers, 100 for

each of the 3 stages of the pre-university educational system (preschool, primary, middle, respectively 50

from the urban and 50 from the rural environment in each category) and 50 teachers each from high-

school and the university educational system. The data collection tool was a questionnaire consisting of

12 items (9 closed items and 3 open-ended items).

O1: Knowledge of the opinion of teachers about the level of correlation between the current organization

of the educational system in Romania and IE practices (I1, I2, I3);

O2: Knowledge of the opinion of teachers about their own need for IE training (I4, I5, I6, I7, I8);

O3: Identifying the teachers’ experience in activities with students with special needs (I9, I10, I11); O4:

Prioritizing teacher training in relation to the main areas of IE (I12).

3.Presentation and Analysis of Results

The systematization, presentation, analysis and interpretation of the data collected through the

questionnaire will be made in accordance with the set objectives. In the data analysis, we marked U =

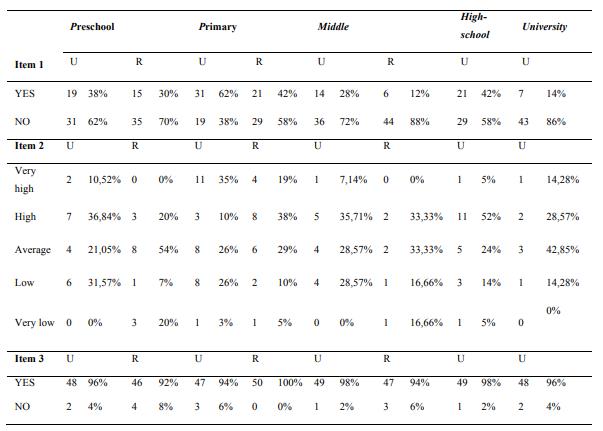

urban, R = rural. For O1, the data were collected through the items I1, I2, I3. Table 1 shows the data

obtained.

The results obtained for Item 1- Do you consider that the current organization of the educational

system in Romania enables real practical implementation of inclusive education? - indicate the fact that

in urban areas, the affirmative opinions of teachers fall between a minimum of 28% at middle level and a

maximum of 86% at university level, with close values of the options of pre-school teachers - 38% and

31% for primary teachers. In rural areas, where we compare only 3 levels (preschool, primary, middle),

the affirmative opinions of teachers fall between a minimum of 12% (middle-school teachers) and a

maximum of 42% for respondents from the primary level. It follows that those who mostly appreciate the

correlation between the current organization of the educational system in Romania and the practices of

inclusive education are university teachers (urban areas), whereas those who strongly contest it are

teachers from the entire rural education: secondary, 88%; preschool, 70%; primary, 58%.

The results obtained for Item 2 - To what extent can the practical implementation of inclusive

education be achieved? (for those who regarded this as possible) reveal the fact that in urban areas, the

most positive view on this issue is provided by primary school respondents, 35%. In contrast, with very

little confidence in this possibility there are the pre-school, middle-school and university teachers, each

with 0%. In rural areas, a higher confidence in this possibility was manifested by primary teachers,

12.5%, with pre-school teachers, 20%, at the other end. Overall, the highest confidence in the actual

possibilities to put IE into practice was revealed by the affirmative answers of primary school teachers,

35% from the urban and 19% from the rural areas.

The results obtained for Item 3 - Do you find it necessary to address the educational curriculum in

terms of the integration of children with special needs? - indicates that both in the urban (between 94% at

primary and 98% at middle and high-school level) and rural areas (between 92% at pre-school and 100%

at primary level), teachers support inclusive education to a great extent. The data allow us to state that the

awareness of the need to integrate children with special needs is highly developed at all the subjects from

the investigated group.

For O2, the data were collected through items I4, I5, I6, I7, I8. Table 2 (Annexes) shows the data

obtained.

The results obtained for Item 4 - Do you consider it important to train teachers for inclusive

education? - indicate a high level of importance given by the respondents to IE teacher training. In urban

areas, the results are placed on the upper threshold, with levels ranging from 96% (high-school teachers)

to 100% (pre-school, university). In rural areas, all the 150 - 100% - respondents, from all levels,

responded affirmatively. The data show a very high awareness of the need for IE training at 87.25% of

the investigated group (Table 2, Annexes).

The results obtained for Item 5 – Is your professional development for inclusive education a

priority? - indicate two aspects: a high percentage of teachers interested in this component of their

training; a decrease of this training need, as the students’ age increases. If for the urban environment,

these aspects are mostly prioritized by primary teachers (92%), this percentage decreases successively

(72%, middle school; 60% high-school) reaching a minimum of 42% for higher education. For rural

areas, the interest is high but not at the same level (between the minimum of 80% at middle-school

teachers and the maximum of 94% at pre-school teachers) and the interest decreases as the educational

level rises. For the whole sample, 75% of the respondents say that IE is a priority for them (Table 2,

Annexes).

The results obtained for Item 6 – Do you have teaching knowledge/skills in working with students

with special needs? – aimed at a self-assessment of teachers’ acquisitions in IE. The data show, for the

entire sample, a very high proportion of teachers (66%) who admit that they do not have adequate

competences in IE. The least trained in IE are university teachers (92%), closely followed by those in the

urban preschool (84%). With equal scores there are the teachers in urban primary and middle education

(66%). The only ones who feel well instrumented for IE are high-school teachers (62%). In rural areas,

more than half of primary teachers believe that they are trained appropriately to work in IE (64%), while

in kindergarten and middle school the lack of the specific training is felt to a very large extent (66%,

respectively 80%) (Table 2, Annexes).

The results obtained in Item 7 - Have you attended, in the last 6 months, training (courses) for

students with special needs? - indicate a differentiated concern of teachers for IE teacher training. Very

little involved in these courses were teachers from urban areas (preschool, 6%; primary, 8%; high-school)

while urban middle-school teachers (72%) were really concerned about this issue. A surprising result is

that academic teachers were not involved at all (0%) in this process. In rural areas, at preschool (26%)

and primary (16%) teachers the concern to participate in IE training is 4, respectively 2 times higher than

at their urban peers, while at middle-school teachers it is much lower (only 10%). There prevails, for the

whole sample, a significant and worrying lack of involvement of teachers in IE training (67.29%), which

supports the urgent need to design and conduct such approaches (Table 2, Annexes).

The results obtained for Item 8 - If YES, specify the name and the organizing institution -

reconfirms what the Romanian teacher training system shows as a trend. We refer to the small number of

teachers who participated in such courses and indicated the institution providing the training. The

respondents from the university did not participate at all in IE training while teachers who engage mostly

in this activity are teachers from the rural primary education (22.86%). Among the respondents who

answered affirmatively in relation to participation in training courses for students with special needs (see

item 7) there were some of them who did not answer the question in item 8. The institutions nominated as

organizing training courses for IE (by those who responded affirmatively to item 7) are minimally

represented by universities (2.86%) and maximally by the Teaching Staff Resource Centre/Casa Corpului

Didactic (68.57%). Regarding the type of training courses, the Course on integrating children with special

educational needs presents the highest percentage (48.28%), followed by the courses on Psycho-pedagogy

(41.37%) and on Anti-stigmatization (3.44%.).

For O3, the data were collected through the items I9, I10, I11.

The results obtained in Item 9 - Throughout your experience, have you ever had students with

special needs in your class? – highlight the fact that 235 teachers (158 from the urban - 63.20% and 77

from the rural areas - 57.33%) out of the total of 400 respondents have worked with this category of

students. Most of the teachers in this situation are those in kindergarten, rural areas (70%); middle school

(78%) and high-school, urban areas (86%). Those who worked least with students with special needs are

university teachers (28%) and rural primary teachers (34%) (Table 3, Annexes).

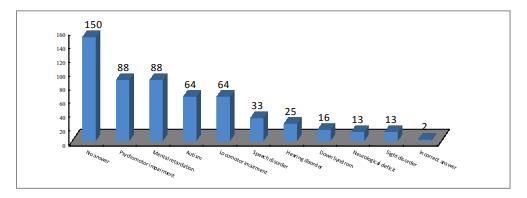

The results obtained for Item 10 - If YES, specify the type of special need/deficiency - allow the

finding of a relatively large diversity of experiences of teachers in relation to students with special needs,

for the whole sample. These are: 1. mental retardation and psychomotor impairment (each mentioned 88

times); 2. autism (64); 3. locomotor impairments (34); speech disorder (33). At the other end, teachers

worked least with students with special needs such as: 1. neurological deficits and impaired hearing (each

mentioned 13 times); 2. Down syndrome (16) (Figure

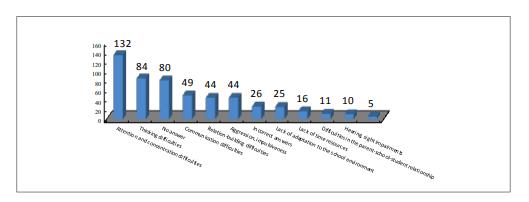

The results obtained for Item 11 - What do you think are the 3 most important issues that you faced

during classes with students with special needs? – reconfirm the painful realities of contemporary

society: the increasing number of children with attention and concentration difficulties (132 times) both in

the urban (67) and rural areas (65); thinking difficulties (84); communication difficulties (49); networking

(44); aggressiveness, impulsiveness (44). Most seldom of all, teachers think that they come across

difficulties related to the stigmatization of children with SEN by other children (5). These types of

responses do not really identify the difficulties of the IE process, but only certain categories of special

needs. However, some respondents also indicate real problems of the process, such as: the student’s and

family’s failure to adapt to the school environment (25); lack of sufficient time resources (16); difficulties

in the relationship parent - school - student (11) (Figure

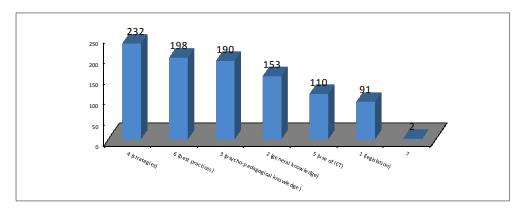

For O4, the data were collected through item 12. The results for

shown in Figure

children with various special needs (232 teachers); b. examples of best practices in inclusive education

(198); c. specialized psycho-pedagogical knowledge in inclusive education (190). There was found a

weaker interest for issues such as: legal issues underlying the process of inclusive education in

Romanian/international law (91).

4.Conclusions

The investigation conducted by us revealed both problems of how to achieve IE in Romanian

education and suggestions for overcoming them. By relation to the assumptions made at the beginning of

our research, we found that two hypotheses were confirmed and two were invalidated, as follows:

education is stronger than that of teachers in higher education -

importance of their training for inclusive education, 87.25% of the investigated group (according to the

data from item 4). The data from item 5 gives us arguments to validate the hypothesis and claim that

teachers from pre-university education manifest a greater need for IE than those in the academic

environment (primary 92%, middle 72%, high-school 60%, university 42% - far below the average of the

sample, 75% of respondents having said that IE is a priority for them). Specific hypothesis 1 is also

supported by the confirmed need of teachers to participate in training courses and training in IE

(according to the data from item 7), particularly through relatively surprising data showing that university

teachers were not involved at all (0%) in this process.

to data from item 4), only 42% of university teachers considered their professional development a priority

for IE (according to data from item 5). Caught between so many specific needs, they do not negate the

need for this training but state that they engage little in IE (at the declarative level) and not at all at the

actual level (according to item 7, where 100% of the academia respondents declared that they did not

participate in training or courses on working with students with special needs). It is possible that

university teachers may not meet students with special needs too often and hence are not motivated to get

involved in IE training or be forced to leave this matter in the background.

The

education is manifested most strongly in primary education –

urban and rural primary education showed the strongest need for IE training compared to all the other

peers from pre-university education (92% in urban, 82% in rural areas, 87% the average for primary

compared to 75.25 the average for the entire sample, as shown by the data from item 5). The teachers

from the primary level - rural areas (16%) are more interested in attending training courses compared to

teachers from the primary level - urban areas (8%). The living environment and conditions may determine

the presence of a large number of children with special needs in rural areas, and consequently a higher

need for IE teacher training. The urban primary school teachers participating in training is low compared

to teachers from the other educational cycles. The percentage of teachers from rural areas who attended

training courses is lower than that of pre-school teachers (16%), but higher than those of middle-school

teachers (10%) (according to data from item 7).

The

education is manifested in urban areas to a higher degree than in rural areas –

all pre-university teachers, IE training is important, the ratio ranging between 96% and 100% (according

to the data from item 4). However, teachers in rural areas attach much greater importance to this training

(100%), compared to those in urban areas (79, 60%) (according to data from item 4). Regarding the

priority for IE, the ratio varies between 60% and 72% for teachers in pre-university education. We have

found a high proportion of teachers in rural areas that prioritize this training (85, 33%), unlike teachers in

urban areas (69, 20%) (according to data from item 5). The importance and significance that teachers

attach to inclusive education are demonstrated by participation in training courses, the teachers in rural

areas (preschool 26%, primary 16%) to a higher extent than teachers in urban areas (preschool 6%,

primary 8%). The increased interest for participation in these courses is highest (72%) for middle-school

teachers in urban areas. These data are added to those collected for items 6-12, among which we mention

the most relevant: very high percentage of teachers (66%) who admit that they do not have adequate

competences in IE (item 6); significant and worrying lack of involvement of teachers in IE training

(67.29%) (item 7); more than half of the sample (235 teachers - 158 urban, 63.20%, and 77 rural, 57.33%,

- out of a total of 400 respondents) admits to having worked with students with special educational needs

(item 9), although not prepared enough in this regard; the professional development lines most expected

from an IE training course are: specialized strategies for working with children with various special

needs; examples of best practices in IE; specialized psycho-pedagogical knowledge in the field of IE

(item 12).

All the data presented allow us to conclude that the

teacher training in Romanian education (pre-university (all levels) and university)? –

with different intensities and in different percentages, with different forms of expression and assumption,

this need is manifested throughout the entire course of Romanian education, from preschool to the

university level. Also, the

training -

The obtained data are consistent with results of other studies. It is necessary to recognize that we

need training for IE, this being a first good step, but not enough. All the more so as “very little is known

about how skills for effective inclusion are developed, or about how to influence teachers’

epistemological beliefs in order that they might be reflected in their practices. We know that teachers

enter the profession and the initial period of preparation with beliefs about teaching and learning that are

intransigent and hard to change (Jordan, Schwartz, McGhie-Richmond, 2009). On the other hand, there

are numerous conclusions and suggestions of specialized fora (UNESCO IBE, 2009), elaborated for

Public Policies, Learners and Teachers, International Cooperation. Two of these refer to IE teacher

training and are in perfect agreement with the results of our study: 1. “Train teachers by equipping them

with the appropriate skills and materials to teach diverse student populations and meet the diverse

learning needs of different categories of learners through methods such as professional development at

the school level, pre-service training about inclusion, and instruction attentive to the development and

strengths of the individual learner”; 2. Support the strategic role of tertiary education in the pre-service

and professional training of teachers on inclusive education practices through, inter alia, the provision of

adequate resources” (idem).

References

- Accessed August 30th, 2016.

- Bukvić, Z. (2014). Teachers’ competency for inclusive education, The European Journal of Social and

- Behavioural Sciences EJSBS, 1586-1590.

- Bustos, R., Lartec, J., Joy De Guzman, A., Casiano, C., Carpio, D., Tongyofen, H. S. (2012) Integration of Inclusive Education Subject in the Curriculum of Pre-service Teachers towards Transformation: Exploring its Impact and Effectiveness, The Asian Conference on Education 2012, Official Conference Proceedings, 1446-1474.

- Florian, L.&Rouse, M. (2009). The inclusive practice project in Scotland: Teacher education for inclusive education, Teaching and Teacher Education, 25, 594–601.

- http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Policy_Dialogue/48th_ICE/ICE_FINAL_REPORT_eng.pdf, Jordan, A., Schwartz, E., McGhie-Richmond, D. (2009). Preparing teachers for inclusive classrooms, Teaching and Teacher Education, 25, 535–542.

- Jovanovic, O., Rajović, V. (2013). The Barriers to Inclusive Education: Mapping 10 Years of Serbian Teachers’ Attitudes Toward Inclusive Education, Journal of Special Education and Rehabilitation, 14(3-4), 78-97.

- López-Torrijo, M., Mengual-Andrés, S. (2015). An Attack on Inclusive Education in Secondary Education. Limitations in Initial Teacher Training in Spain, New Approaches in Educational Research, Vol. 4., No. 1, 9-17.

- McCrimmon, A. W. (2015).Inclusive Education in Canada: Issues in Teacher Preparation, Intervention in School and Clinic, Vol. 50(4) 234–237.

- McIntyre, D. (2009). The difficulties of inclusive pedagogy for initial teacher education and some thoughts on the way forward, Teaching and Teacher Education, 25,602–608.

- Sazak Pinar, E. (2014). Identification of inclusive education classroom teachers´ views and needs regarding in-service training on special education in Turkey, Academic Journals, Vol.9 (20), 1097-1108.

- UNESCO IBE (2009). Inclusive Education: the Way of the Future, Final Report of the 48th session of the

- International Conference on Education (ED/BIE/CONFINTED 48/5). Paris: UNESCO IBE, Vaillant, D. (2011). Preparing teachers for inclusive education in Latin America, Prospects, 41, 385–398. Yadav, M., Das, A., Sharma, S., Tiwari, A. (2015). Understanding teachers’ concerns about inclusive education, Asia Pacific Educational Revue, 16, 653–662.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Cojocariu, V., Balint, N. T., Anghel, M., & Alina – Mihaela, C. (2017). Comparative Study On The Identification Of Teachers Need For Inclusive Education Training. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 652-662). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.80