Abstract

Architecture, seen through the lens of children involves a remarkable duality between metaphor and pragmatism and implies a continuous dialectic between the two. For a child, experiencing a space, along with its purely physical evaluation has an intense intrinsic value, thus allowing spatial judgement and appropriation from both a symbolic and pragmatic point of view. In order to detect children’s unique and fascinating way of approaching and internalising notions related to architectural experiences, a study has been initiated during architecture classes1. All these methods of space perception were employed in order to evaluate which method represents the most effective instrument for teaching and introducing architecture notions to children in primary school, between the ages of seven and twelve. The study, through these comparative learning tools, is representing an important reference for teaching methodology in architecture classes.

Keywords: Architecture teachingcreative methodologyteaching methods

1.Introduction

The national decision of introducing architecture curricula for optional classes, made a few years

ago in Romania, was an important an useful decision, acknowledging the determinative impact of

architecture and built environment in shaping our children as individuals. The decision was even more

welcomed as recent studies, such as those of Rissotto and Giuliani (2008), Francis and Lorenzo (2002),

are warning that children are lacking, more and more every year, their urban-sense, the city knowledge

and the spatial cognition, due to minimizing their interaction with their environment. Architecture classes

can be thus a source of compensating the deficiency between the distant relationship between children

and their built and natural environment.

In addition to these benefices, teaching architecture in schools can be a useful instrument of

facilitating interdisciplinary approach and methodology, offering a support for applying different

competencies and abilities developed by children at other disciplines. Moreover, because of its place

outside of didactical patterns, architecture classes can be a real stimulus for teacher’s creativity, as well as

for children’s attachment and involvement degree inside the class.

Implementing architectural curricula to children in primary schools can be, in the first phase, both

provocative and experimental for teachers. Beside didactical skills and educational expertise, it requires

substantial knowledge about architecture theory and thus, in the first stages, it is recommended to double

the teacher with an architect or architecture student, until the teacher feels comfortable with the subjects.

In addition to didactical skills and architecture knowledge, when teaching architecture in primary schools,

it is important for teachers to know particularities of space perception in children, in order to simplify the

process of choosing of proper method for each theme, adapting each method to the proposed purpose and

ensuring the achievement of projected objectives.

The present study is aiming to recommend a framework for didactical methods in teaching

architecture in primary schools, depicted from two years of research during architecture programme2 and

from a significant didactical experience. The subsequent objective is detecting the evaluation principles,

the transactions children carry through negotiating with space determinants, and, last but not least,

detecting the principles upon which they reckon during the process of internalizing and subjectively

appropriating the space and built environment. The information emerged from this first objective is to be

used in accomplishing the three major goals of implementing architecture curricula: children’s learning,

using and designing spaces and environments. The paper will provide a useful instrument for teachers,

helping them choose the right teaching methods in architecture class.

The study will focus on the duality of children’s way of thinking and perceiving. Metaphoric, as

well as pragmatic, these two modalities of adjusting to immediate reality are requiring teaching

techniques that incorporate both of them, in different doses, as every particular situation requires it.

2.Paper Theoretical Foundation and Relating Literature

Existing literature on children’s space and place perception is a valuable criterion for choosing and

applying the proper methodology when teaching architecture in primary school. A short review that

follows, having non-exhaustive intentions, can be taken into considerations especially by teachers and

also by architects when teaching architecture curricula, in order to maximize the potential and affordances

that it can offer. Is to be remarked all over the below-mentioned studies, the duality between the two

claimed concepts: pragmatism and symbolism, specific for children’s way of thinking and perceiving.

A partisan of exterior spaces in children’s everyday life and experience, Moore (1986) claims that

when playing in the exterior environment, children’s feelings about each other are more positive. Moore and Wang (1997) asserted that outdoor environments stimulate all aspects of children development, being 2Architecture classes took place atBanatean National College, during 2015-2016, Class no. IIC, Professor Delia Florescuand at “Avram Iancu” Gymnasia School, during 2013-2014, Class no. IVC, Professor Mariana Popescu.

more effective than indoor stimulation. Moore and Young (1978) divided the different valences of the

space and experiences of the environment, splitting them into physical/ physiographic space, social space

and inner or subjective space. Children’s and adults’ hierarchies differ in their priorities, children placing

on superior rank the inner space that belongs to their subjective reality. When perceiving and evaluating a

space, the child cannot extract the strictly configurative aspects of that space. The first perceived aspects

are the ones related to their subjectivity. Evaluation of space is being made in parallel with the coexisting

factors, these being able to depreciate or to over-evaluate the same space. This aspect is very important

when choosing the right approach and method in teaching architecture programme to children.

Wapner and Demick (2000) identify three types of connections between the environment and

children: cognitive, affective and evaluative. The cognitive experience is offering stereotypes of thinking

and skills for solving problems. The affective experience is providing emotional abilities so that the

feelings can be expressed. The evaluative experience is the one that creates judgement values toward the

environment (Kellert 2002). Again, major differences between adults and children. If for an adult, the

cognitive experience is set on a detached first place, for children there is the affective one that is

remarked first.

In the context of such a complex world, sometimes complex enough even for adults, children, due

to a self-protection mechanism, are trying to structure this complexity, reducing it to an easy to

manipulate scheme. We can identify this principle postulated by Spencer (2008) into children’s spatial

behaviour, but this competence is frequently underestimated by adults.

In a situation in which children, besides a static perception of a space, are being implied in a

dynamic participation, especially a motion one, the satisfaction sentiment is rising and it will persist as a

memory in their conscience for a much longer period, according to Sebba (1991). When mediated

through a positive andsubjective involvement, space appropriation, space perception and in some cases

even place attachment is being favoured. Siegel and White (1975) claim that active actions into a space

facilitate multiple perspectives of that space. Passive experimentation of a certain space or environment is

simpler and more superficial than the one involving movement.

The subject of Korpela, Kytta and Hartig’s researches (Korpela et al. 2002) was children‘s

predilection for choosing special places, selecting two categories of preferences: places with cognitive

function and places with emotional function.

Sener (2006) discovered that by engaging children into the process of building design, architecture

can become more empathic, moulded on children’s own way of perception, encouraging thus a design

process with more viable results. Bell (2008) asserted that when spatial references are not available for

children of nine years old, they better reproduced large spaces, “vista spaces”, than small ones, “object-

spaces”3. Also, he claims that “different strategies (…) might be used to solve a similar problem in two

different size spaces” (p. 18).

Information provided by environmental and behavioural studies must be completed with relevant

data from children psychology, who placed early scholar age (6/7/ years – 11/12 years) inside the period

of concrete operations, according to Jean Piaget (2005). This is the time for complex developments, when cortical areas will develop, together with certain capacities are beginning to develop, but the first ones are 3Based on Montello (1993)’s classification of space taking account of its scale, related to human body (figurative spaces, smaller than human body, divided in pictorial spaces and object-spaces and vista spaces, bigger than human body)

motion, followed by sensorial regions. The visual field is expanding, allowing children to differentiate

better chromatic nuances. The spatial perception is developing as well because all the experiences

children have been accumulated. This will determine a higher sense of spatial orientation and directions

(left/ right, forward/ backwards). In parallel with all these evolutions, there is a temporal development

happening as well, as the child is referring constantly to some repetitive facts in his life.

According to Cobb (1998), in this period of middle childhood, children are being genetically

scheduled for exploration and creating a connection with nature. They understand the environment

through play (Moore and Young 1978), playing being the factor that stimulates all cognitive capacities.

The direct contact and active experiences of a child with the environment allow him to develop logical

thinking (McDevitt and Ormrod, 2002), to explore, to imagine and discover, as mentioned by Olds (1989)

and Kellert (2002). In conclusion, children’s development and operating are being shaped by the

transactions and interactions they have with the environment and people.

3.Findings and Recommendations. Contribution to Existing Practice in Educational Field

Due to its recent introduction into educational field, teaching architecture to primary school

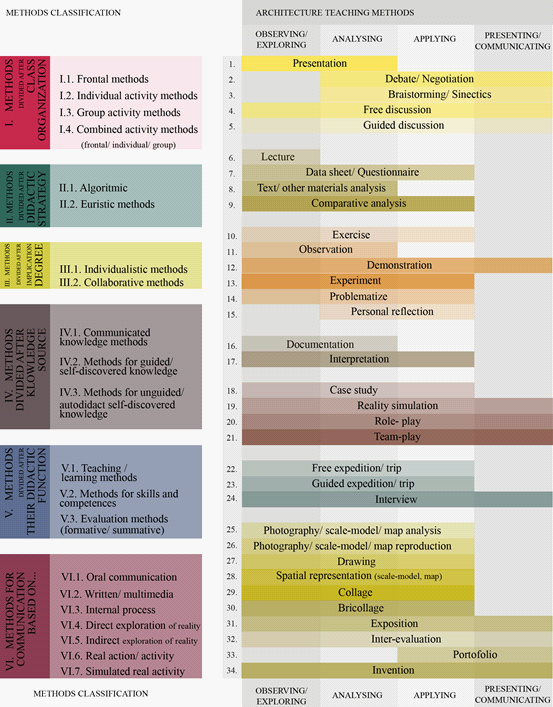

children requires adapted methods and methodology to its specificity. A multidimensional diagram is

being conceived, comprising an extensive list of didactic methods, offering a teacher-friendly framework,

useful in preparing architecture classes.

Architecture curricula proposed by “

Romanian primary schools, is based on few major components, around which is being constructed the

entire didactic scenario: Observing/ Exploring; Analysing; Building/ Applying; Presenting/

Communicating. All these four steps, each with its characteristic potentials and affordances, are important

to be covered as methodologies, because of the different skills, abilities and competencies they develop.

The major contribution of the diagram presented below is that it can offer a valid support for teachers in

architecture class, providing an extensive combinatory list and guiding them in choosing the right method

to achieve the proposed objectives, adapted to the specific components of the four didactic scenarios

(observing, analysing, applying or presenting).

Educational discourse and methodology of architecture classes must adapt to these specific steps

and to specific objectives settled for every lesson. Figure

considering many factors affecting didactic process when teaching architecture curricula. The left column

is indicating different types of methods, classified by different criteria, while the right column is

mentioning different specific methods, recommended for the four components of didactic scenario

specified by “

Previous studies had shown a few important children’s particularities in perceiving, thinking and

appropriating spaces and places, so that methodology and didactical methods must comply with these

specifications. Besides the significant cognitive aspect of the lessons, architecture classes must be

associated with the affective dimension, assuring thus the maximum efficiency through children’s

attachment and bonding with the teacher or with the subject. Architecture didactic process must also be

conceived as most flexible and creative as possible, offering diverse didactic scenarios to allow children’s

creativity to develop. The balance between the pragmatic and metaphoric aspects of architecture lessons

must be kept in mind and in control by the teacher. Outside play is an important catalyst for learning and

when it is doubled by playing, by a dynamic participation or by personal involvement, educational

process can be finalized with successful implemented objectives.

Combining all the methods presented by the diagram, during architecture classes is an issue falling

upon teacher’s liability, but choosing the right combination can ensure acquiring of theoretical

particularities summarized above from the previous chapter. A few following examples will display the

possible diversity in combining didactical methods, offering a guideline of how can be combined

pragmatic with symbolic methods when teaching a certain architecture theme.

As seen in the previous chapter, there are many ways to perceive space and build environment.

There are direct, experiential perceptions (for example

through descriptive items (implying thus children’s creativity and imagination) or through reproductions

of space itself (that stimulates cognition, spatial and tridimensional abilities). Free expeditions are a good

opportunity for a teacher to communicate and present information to children (

self-discovered knowledge (IV.2.Methods for guided self-discoveredknowledge and IV.3.Methods for

unguided/ autodidact self-discovered knowledge with 22.Free expeditions). Whenever visual perception

is doubled by indications and previous guidance, it can be efficient mostly (not exclusively) for the

guided information, in the detriment of other things that children usually perceive when unguided. When

perceiving a certain space in the context of obstructing visual perception, all other senses are being

activated much more than in the presence of the visual one.

Taking photos (25.Photography analysis and 26.Photography reproduction) of a given theme,

subject to personal interpretation can be a method to involve children’s

making skills and competences (V.2), as well as for evaluation (V.3).

Observation (11) and interpretation (17) can be chance for a collaborative process (III.2).

“Acclaiming a façade” is a game for carefully observing the rhythm on a façade, for internalizing the

visual information (

synchronization must be present in this collaborative process.

“Architect”, the “Beneficiary”, the “Mayor”, the “Neighbour”, aside of its well known role in

and simulated real activities (VI.6 and VI.7), this game is a provider of internal process (VI.3).

Another prescription for effective teaching is when correlated the lesson itself with pragmatic

delights for children (choosing for example scale-models of eatable houses), rising through their interest

an increasing they will to collaborate.

Expositions and portfolios, based on individual or collaborative methods, are a good opportunity

for inter-evaluation and being aware of the final product of children’s work and cognition.

The questionnaire can provide important information when evaluating space perception in

children, sometimes important in completing symbolic and metaphoric information that cannot be drawn.

Doubled with the drawing of the same perceived space (the drawing being consider a provider of

pragmatic information – items being present inside the room, as well as for metaphoric information)

evaluation is gaining a bigger validity, completing the missing details of the questionnaire. When asked to

describe their room, most children enumerated several items or several feelings associated with the room.

When asked to draw their house, numerous other details were being added. Drawing can be a pretext for

transposing reality (

Based on the above-mentioned scheme, there can be conceived atypical combinations. See for

example

Sustainability Theme, which is a game for successive cutting of the same loaf, so that there will be as

many beneficiaries of slices as possible. Another uncommon example as well is the association of

sharing the same drawing, with the result of obtaining a final drawing, raising children’s awareness in

their own contribution of the whole and boosting team spirit.

exploring its own residential waste products, then with

waste products and creating an object for playing, finalizing with

and explaining the process and the final innovation created from waste products.

4.Conclusions

Creative curricula need creative and proactive teaching methods. In order to achieve operational

objectives, teachers must consider children’s particularities in perceiving, using and designing spaces and

built environment. Teachers must conceive participative methods to raise children’s interest and to ensure

their constant interest.

The importance of choosing the right methods in teaching is an issue that cannot longer be

contested. The diagram presented in

training in architectural theory) when preparing architecture lessons and so are the short combinatory

examples presented in the previous chapter.

Moreover, taking account of every topic of architecture’s class and its subsequent objectives, there

can be chosen that specific methods and methodology (or specific combinations) that can mark a

pragmatic or a symbolic pattern of the lesson. The ratio between the two is depending of teacher’s

didactical skills.

Further documentation is being required to complete the second chapter of this study, to identify

supplementary relevant data that can help in the methodology of teaching architecture on primary school.

Also, the study can be completed with additional creative teaching methods, in order to obtain a

comprehensive list. Aside of its limitations, the present study offers a new perspective about teaching

architecture curricula to primary school, establishing the foundations for future studies approaching this

theme.

Acknowledgements

Data of this study resulted from documentation derived from architecture teaching in Romania, at Banatean National College, during 2015-2016, Class no. IIC, professor Delia Florescu and at “Avram Iancu” Gymnasia School, during 2013-2014, Class no. IVC, Professor Mariana Popescu. The authors would like to thank all children and professors participating to this program.

References

- Bell, S. (2008). Scale in children’s experience with the environment. In C. Spencer & M. Blades (Eds.)

- Children and their Environments: Learning, Using and Designing Spaces, Cambridge University Press, 13-25.

- Cobb, E.(1998). The Ecology of Imagination in Childhood, 1959, Spring Publications.

- Francis, M., Lorenzo, R. (2002). Seven realms of children’s participations. In Journal of Environmental Psychology, 22(1), 157-169.

- Kellert, S. R. (2002). Experiencing nature: affective, cognitive and evaluative development. In Children and Nature: Psychological, Sociocultural, and Evolutionary Investigations. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Korpela, K., Kytta, M., Hartig T. (2002). Restorative experience, self-regulation and children’s place preferences. In Journal of Environmental Psychology, 4. pag. 387 – 398.

- McDevitt, T.M., Ormrod, J.E. (2002). In Child Development and Education. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

- Montello, D. R. (1993). Scale and multiple psychologies of space. In A. U. Frank & I. Campari (Eds.), Spatial information theory: A theoretical basis for GIS (pp. 312-321). Proceedings of COSIT '93.

- Berlin: Springer-Verlag, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 716. Source: http://old.nbu.bg/cogs/events/2003/materials/christian_freksa/montello_scale_93.pdf Moore, R. C., Young, D. (1978). Childhood outdoors: toward a social ecology of the landscape. In I. Altman & J. F. Wohlwill (Eds.), Children and the Environment New York: Plenum Press.

- Moore, R.C. (1986). The power of nature orientations of girls and boys toward biotic and abiotic play settings on a reconstructed schoolyard. In Children’s Environments Quarterly, 3(3).

- Moore, R.C., Wong H. (1997). Natural Learning: Rediscovering Nature’s Way of Teaching. Berkeley. CA. MIG Communications.

- Olds, A. R. (1989). Psychological and physiological harmony in child care center design. In Children's Environment Quarterly, 4, 6, 8-16.

- Piaget, J. (2005). Children’s psychology, Bucuresti: Printimg house Cartier Polivalent.

- Rissotto, A., Giuliani, M.V. (2008). Learning neighbourhood environments: the loss of experience in a modern world. In C. Spencer & M. Blades (Eds.) Children and their Environments: Learning, Using and Designing Spaces, Cambridge University Press, 75-90.

- Sebba, R. (1991). The Landscapes of Childhood. The Reflection of Childhood's Environment in Adult Memories and in Children's Attitudes. Environment and Behavior, Vol. 23, No. 4 395-422.

- Sener, T. (2006). The children and architecture project in Turkey. In: Children, Youth and Environments. Vol. 16(2), pag. 191-206.

- Siegel., A. W., White, S.H. (1975). The development of spatial representations of largescale environments. In H.W.Reese (Ed.), Advances in Child Development and Behavior, Vol. x, 51-83.

- New York Academic Press Spencer, C., Blades, M. (2008). Children and their Environments. Learning, Using and Designing Spaces. Cambridge University Press.

- Striniste, N. A., Moore, R. C. (1989). Early childhood outdoors: a literature review related to the design of childcare environments. In Children's Environment Quarterly, Vol.6, No.4, 25-31.

- Wapner, S., Demick, J. (2000). Assumptions, methods and research problems of the holistic, developmental, systems-oriented perspective. In S. Wapner, J. Demick, T. Yamamoto & H.

- Minami (Eds.). Theoretical Perspectives in Environment-Behavior Research: Underlying Assumptions, Research, and Methodologies, New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 21-37.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Negrișanu, D., Havași, B., & Florescu, D. (2017). Teaching Architecture to Children. (In)Between Metaphor and Pragmatism. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 558-565). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.68