Abstract

This paper presents the results of an exploratory research conducted by the authors with the support of students participating in Economics classes within a Technical University in Bucharest, Romania. At the core of the exploratory research are (i) the perspective of „Y” generation students on gamification and (ii) the ability of gamification to influence students in technical higher education in order to achieve better learning performances during Economics classes. Quantitative and qualitative research methods were employed to perform this exploratory research around two main construct: enjoyment and perceived usefulness of gamified learning activity. The exploratory research reveals that gamification in the described context has potential to increase students motivation in learning Economics. The results of the exploratory research boosts the understanding of the gamification phenomenon as a persuasion tool in teaching non-technical disciplines - such as Economics - in a technical higher education environment. However, introducing gamification can be difficult within an inertia context, even if macro environment factor (4th Industrial Revolution accompanied by „Internet of Things) places gamification on learning as a theme that requires attention at the level of Romanian higher education system. Thus, implications and future research are also included in the paper.

Keywords: Gamificationtechnical higher educationEuropean MillennialsEconomics

1. Introduction

Romanian higher education system is facing challenges coming from its micro and macro

environment. Following the screening of Romanian higher education system environment, we used

STEEPLE analysis tool that asses the factors that can remove or lower barriers to achieve better learning

performances. Therefore, for this paper work we have selected the

environment factor, more specific, the 4th Industrial Revolution accompanied by „Internet of Things”.

However, all social, economic or cultural changes in Romania must be seen as relevant sources of

challenges for today’s Romanian universities, even if they are not specifically addressed in this paper

work.

The students who belong to generation „Y” (Millennials), represents the major category of

stakeholders of the Romanian higher education system that is at the core of this exploratory research. As

elsewhere, in Romania it is becoming increasingly important to motivate students to allocate time for

learning: student’s time dedicated to learning activities becomes a scarce resource nowadays. In making a

choice on how spending time, learning activity is competing against many other available options, most

of them generated by the advanced technological status of the universities’ environment. It is expected

that the second major category of higher education system stakeholders - professors - becomes

increasingly aware of the higher education environment dynamics and, particularly, of the changing

characteristics of today’s students, whose needs they have to address.

Higher education system as social system requires coping with the environment in which is

operating. We need to consider what has been changed is the environment in which universities are

acting. More, this is of extreme relevance in the context of the 4th industrial revolution.

Roy and Zaman (2016), in a study based on gamification, draw heavily that it is looked at as a

possible solution for the observed dropping levels of learners’ motivation. Previous research has

presented inconclusive findings as to the demonstration of whether gamification works or not.

This paper reports about the perspective of generation „Y” students (within a Romanian technical

university attending Economics classes) on using gamification in teaching Economics and on the ability

of gamification to influence students to achieve better learning performances.

The research question to which this exploratory research aims to answer is: „Can gamification be

more effective than traditional lecturers approach in teaching Economics to „Y” Generation of students

within a technical university?”. The drivers behind this exploratory research are explained under headline

Research Strategy and Method.

The paper is structured as follows: paragraph 2 describes the research approach and findings and

the outcome of this exploratory research are included in paragraph 3. The final paragraph, 4, presents the

conclusion of the exploratory research.

2. Research Strategy and Method

The work included in this paper is based on an exploratory research. The primary driver for

selecting the exploratory research was generated by the need to address all type of questions (what, why,

how) for a deep understanding of Romanian “Y” Generation of students perception in relation to

gamification in the actual context of Romanian higher education system. The primary driver has been

seconded by intention to use this opportunity for helping in establishing further research priorities in this

area (Christoph, 2010). But the core of this exploratory research cannot be separated from the context.

Since the case studies are an adequate research strategy for complex phenomena that cannot be studied

outside their context (Yin, 2013), the exploratory research has been found appropriate for analysing the

use of gamification in Economics classes within Romanian technical universities.

2.1. Context description

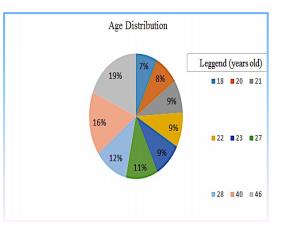

Following the generational theory emerged around 1991 in United States, during 2000, the

researchers Howe and Strauss published

Millennials phenomenon in United States from a sociological point of view. The researchers assign the

expression „Millennial generation” to those individuals born between 1982 and 2004. Subsequent studies

launched the idea that American Millennials are technology savvy (Pew Research Center, 2010).

The advancing of generational theory in the US is accompanied in Europe by initiatives aiming at

expanding on or building upon the results of examining the Millennials phenomena in US. Studies

published in the inception phase of the researches in Europe were aiming at highlighting similarities and

differences on generations of American and European Millennials. Relevant for the context of this

exploratory research is the study revealing that there are „basic similarities in Internet and technology

usage” when comparing European Millennials with US Millennials (Corvi, Bigi, & NG, 2007)”.

Meanwhile, European Millennials on their own became object of consideration for research. In August

2016, the results of a survey conducted1 with the objective of understanding the values, challenges and

aspirations that are driving European Millennials were published. The study specifies, among others:

“Regarding technology, 8 in 10 of the respondents say they feel empowered by current technology”. The

“digital native” label for the Generation Y, as coined by Mark Prensky 10 years ago for US is of

relevance in the context of this paper work also for European Millennials (Prensky, 2005/2006). The

results of studies performed with the purpose of featuring the European Millennials highlights the natural

inclination of the generation Y to technology and the fact that they share the same features as American

Millennials: they are also technology savvy.

Studies performed around 2010 on teaching methods for Generation Y students specify that

„Today’s students [...] have little patience for lectures, step-by-step instruction or thinking or traditional

testing. Compared to their experiences with digital technology, they find traditional teaching methods

dull” (Black, 2010). Generation Y is looking for interactive and participatory learning environments

(Price, 2009). It follows that the vehicle used by a professor to communicate the information is requiring

a fundamental change.

In parallel with the identification of Millennials features and with the marketing of the need for

adapting the teaching methods to the environment – consisting of Generation Y students -, concepts from

other areas migrate to educational services and new trends are emerging. In 2014, a new word has been

introduced in the Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary: „gamification”, with the following definition

„the process of adding games or game-like elements to something (as a task) so as to encourage

participation” (Merriam-Webster's, 2014). „Gamification” started the journey for entering into common

1global market research player Penn Schoen Berland (PSB) published the results of a survey conducted among European Millennials on behalf of Honor (Huawei Group)

vocabulary 7 years behind this date (when first used) and won this recognition at the end of 4 years of

fighting for recognition (Deterding, Dixon, Khaled, & Nacke, 2011).

Defining higher education as a social system requires exchange of information with the context the

system operates in. It is expected that in the learning process, the other major category of stakeholders-

the professors- would consider the technological environment as an interest of the other major category of

stakeholders: the students.

3. €conomia: Game Used as Learning Vehicle in Economics Classes

During one semester (February – June 2016), all the topics corresponding to the Economics

curricula were presented using an interactive teaching style. More specific multimedia slides

incorporating text, images, and charts were displayed on a projection system during the classes with the

purpose of introducing the Economics concepts. In parallel students were provided with detailed support

information for concepts discussed during the classes by email.

For the curricula topic „Monetary Policy”,

Central Bank - ECB) has been added to the above mentioned lecture approach, creating role-playing and

simulation statuses in the process of setting the interest rates in order to keep annual inflation under 2%

over a specific period of time. The aims of using

economic environment simulation, where information such as unforeseen economic shocks, the press

and ECB board members who often provides contradictory advices represents entry data;

setting, and competition.

Muntean (2011) as means of motivating by providing recognition, status, and the potential for

competition among users (Muntean, 2011).

2.1. Research process

any formal training. Instead, the concept of gamification and

the beginning of the class. Students were informed about the rewards mechanism available with the game.

using their smartphones or laptops.

The gamified learning activity was composed of two parts:

The learning activity has been followed by reflection. The aim of reflection was to transfer the

game-based experience and to provide grounds for connecting what included in the game with student’s

daily life experience, in order to achieve broader learning outcomes.

This is an approach recommended and supported by Nicholson (2015): „in order to be effective

[

(Nicholson, 2015)”. Nicholsons encourages professors to lead the students to a reflection when

gamification systems which do not include reflection are used. This action follows Rodgers (2002)

reminder on Dewey’s work, who argued in his works done 100 years ago that without reflection after

action people do not find the meaning in what they are doing (Rodgers, 2002).

At the end of reflection stage the students were asked to voluntarily participate in a survey about

their experience with gamification as learning tool in Economics classes. Questionnaire is the instrument

used (i) to evaluate the attitude of students towards the gamification as a learning tool and (ii) to evaluate

students’ satisfaction level in using gamification compared to classic education tools. The questionnaire

was built around the idea to get a snapshot on the experience of students with two main constructs:

enjoyment and perceived usefulness of gamified learning activity.

For the purpose of this exploratory research, the

its own right, aside from any performance consequences resulting from system use” (Venkatesh & Davis,

2000). Further, the operationalization of the construct within the questionnaire body considered the

recommendation of Goetz et al. (2006), in respect of the need to distinguish two different phenomena in

assessing enjoyment. More specific, through the included questions, students’ trait emotion (intended to

refer retrospectively to cumulative experience in enjoying Economic classes) was an object of

consideration on its own. The state emotion (current enjoyment of the Economics class when

gamification was used in teaching) was treated as a separate object of consideration.

The questions designed for evaluating the

are:

pleasant when using gamification in the Economics’ learning process, compared to the use of other aid

tools for visualizing the information (partial ICT use or no ICT use)

Economics concepts when gamification is used, compared to using the traditional teaching system

Economics concepts/information?

particular system would enhance his or her job performance” (Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw, 1989), with

two specific questions:

Economics enhances my performance in assimilating the information.

process determined a growth of interest for the Economics classes and an increase in the effectiveness of

my learning process.

The above questions are based on a five-point Likert scale with all the sentences scored in a

positive scale: (1–to a very small extend/strongly disagree, 2–small extend/disagree, 3–to a moderate

extend/undecided, 4–to a large extend/agree, 5- to a very large extend/strongly agree ).

Students participating in the survey were asked: (i) to explain their positioning on Likert scale

using as reference the question and (ii) to provide additional feedback about their perceptions and attitude

towards using gamification as learning tool. The questionnaire also asked students: (i) to provide any

further thoughts on increasing the use of gamification in Economics classes; (ii) to provide opinions on

the below degrees of use of information and communication technologies (ICT) in the education process

within sitting classes:

images, charts, sounds, videos, displayed on a projection system in the class and supporting materials by

email – in this specific case.

The requirement to provide opinions on the use of ICT in the learning process must be seen in

connection with and as an extension of the construct “enjoyment”. The survey was answered

anonymously by a pool consisting of 20 students at Technical University of Civil Engineering – Faculty

of Building Services, Bucharest, Romania using the online questionnaire tool.

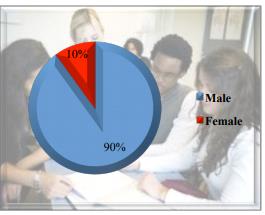

Out of 20 students, 90% are male, 10% are female, 40% report themselves as experienced

computer gamers (accessing in the last month before survey computer games such as League of Legends,

Game of Thrones, FIFA, to name only few), while the other 60% are either non-users or occasional and

unexperienced users of computer games.

3. Findings and Discussion

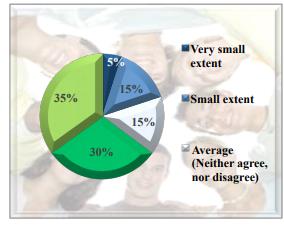

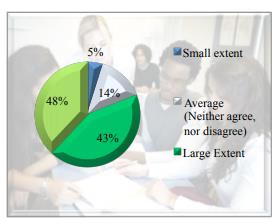

Under this headline, the results of the two main constructs

experience is more pleasant when using gamification in the Economics’ learning process, compared to

the use of other aid tools for visualizing the information (partial ICT use or no ICT use)”, while 15%

have a neutral position (neither agree nor disagree).

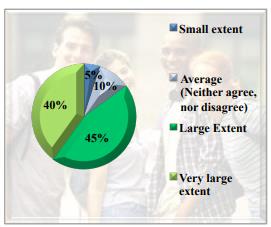

About 85% of the students strongly agree (45% to a very large extend and 40% to a large extend)

with the statement that “It is more pleasant to assimilate Economics concepts when gamification is used,

compared to using the traditional teaching system”.

About 75% of the students find satisfactory the experience with using gamification in

Economics learning process, while 25% find it neutral. None of the participants found the experience

unsatisfactory.

agree (48%) that using gamification in teaching Economics enhanced their performance in assimilating

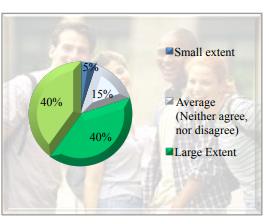

About 80% of the participants agree (40%) and strongly agree (40%) that

the teaching process determined a growth of interest for the Economics classes and an increase in the

the statement to a small extend.

3.1. Student experience

Students found the use of gamification as enjoyable and identified gamification as contributing

beneficially to learning Economics. Students were asked to motivate their position on the Likert scale

in relation to the addressed questions.

Questions addressing the impact of ICT in the learning process highlights:

participants find „unsatisfactory” the learning experience in classes while chalk and blackboard is used

as aid tool for visualising the information during lectures, while 40% find it neutral. While motivating

the answers for degree such as „unsatisfactory”, the following epithets are used by students to describe

the style: „antique” “obsolete”, „ monotonous” or „boring”. Students are also detailing reasons for their

believes: „the attention vanishes after a very short period of time”, „I can’t fix the information if the

dictation and writing speed is too high"; „attention goes away after a short time” . Students which find

this style satisfactory (20%) motivate their satisfaction with reasons such as „it’s an important tool for

teaching and learning”.

85% of participants find their experience satisfactory, while 5% are unsatisfied and 10% are unsure

about. Reasons motivating a high level of satisfaction include: „It stimulates my interest because I have

to think, not just to write like a robot”; „Interaction in the classroom is beneficial to a more effective

learning process compared to the classic style of teaching or „the most effective way of teaching and it

helps me to easily assimilate information", epithets associated with the degree of satisfaction being:

„Interactive” „catchy”

When it comes to the use of gamification in lecturing, 90% of the students finds this experience

„satisfactory”, the most frequently used epithet being „interactive”. Reasons for the high satisfaction

includes: “I paid attention to the classes and it was really a nice experience”, “it was an ingenious way

to make us better understand the topic", "a very effective and interactive way to get my attention".

Results displayed for (i) the two constructs at the core of this exploratory research

and perceived usefulness of Economics gamified learning activity in technical universities

gamification technique in Economics in technical students environment is an effective tool for

enhancing student engagement. Generation „Y” students exposed to the gamification experience -

instructiveness and dynamics in the learning process – suggests higher levels of involvement compared

to the learning process when other teaching methods are used.

More specific the results are very positive, particularly toward enhancing learning, which is one

of the primary objectives of the education. The majority of participants felt that the gamified learning

activity improved their learning. Furthermore, the activity did engage the participants and resulted in a

high degree of enjoyment.

Through these results the effectiveness of using gamification in teaching Economics in technical

universities has been signalled. The positive results of this explanatory research confirm for the

Romanian Generation Y students statements previously made in the literature about the teaching

methods with Generation Y students and further support the use of gamification in Economics classes

while demonstrating its effectiveness.

For the second category of relevant stakeholders of the higher education system in Romania,

this exploratory research provides an understanding of the Generation Y drivers for performance in

learning process.

Within the environment described at the beginning of this exploratory research, it was of

relevance to examine and understand the preferences of Millennials for the learning process for at least

two reasons: (i) provided orientation for the professors - on how to communicate effectively with the

students during the learning process; (ii) highlighted within a particular environment the importance of

accepting the features of an open higher education system.

Millennials or „digital native” generation are independent and they feel empowered by

technology. Incorporating gamification tools to support the teaching process in the class, further sustain

student engagement in learning when games used in the class can be further explored by students using

their own communication tools, which contribute to the effectives of the learning process.

4. Conclusions

Using gamification in teaching Economics for students enrolled with technical universities have

potential to increase student motivation.

As digital natives, students of generation „Y” expect the use of ICT in the classroom. For them

this is natural and therefore they feel attracted by collaborative, interactive and engaging learning

environment: they favour learning environments that incorporate ICT.

However, the results are self-reported within an exploratory research and refer to one particular

implementation of gamification in Economics classes with students within a technical university,

The results of this exploratory research demonstrate that this particular implementation of

gamification – in Economics classes with students from technical university - has beneficial effects, lay

the groundwork and invite for further research into the matter. Further research should be conducted to

secure the potential bias incorporated in the results and to determine other ways in which gamification

can be implemented in education.

Although our work is only one particular use of gamification in education, our results are

promising and other applications of gamification in education should be investigated since there is no

longer an option using old traditional teaching methods in a world of disruptive changes. While

acknowledging that introducing gamification can be difficult within an inertia context, it is a theme that

require\s attention at the level of Romanian higher education system .

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the students participating in this survey - from the Faculty of Building Services - Technical University of Civil Engineering of Bucharest - for helping to address the consideration of gamification in Economics classes and for their involvement in this exploratory research.

References

- Black, A. (2010). Gen Y: Who they are and how they learn . Educational Horizons, 91-101.

- Christoph, S. K. (2010). Exploratory Case Study. În A. J. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Wiebe,

- Encyclopedia of Case Study Research (pg. 372-374). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Corvi, E., Bigi, A., & NG, G. (2007). The European Millennials versus the US Millennials: similarities

- and differences . Preluat de pe http://www.unibs.it/sites/default/files/ricerca/allegati/Paper68.pdf

- Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A

- comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35 (8), pg. 982-1003.

- Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). Gamification: Toward a Definition .

- Vancouver, Canada. Preluat de pe http://gamification-research.org/wp-

- content/uploads/2011/04/02-Deterding-Khaled-Nacke-Dixon.pdf

- Merriam-Webster's. (2014). Collegiate Dictionary. Preluat de pe http://www.merriam-

- webster.com/dictionary/gamification

- Muntean, C. I. (2011). Raising engagement in e-learning through gamification . Preluat de pe

- http://icvl.eu/2011/disc/icvl/documente/pdf/met/ICVL_ModelsAndMethodologies_paper42.pdf

- Nicholson, S. (2015). A RECIPE for Meaningful Gamification in "Gamification in Education and Business". În T. Reiners, & L. C. Wood, Gamification in Education and Business. Springer International Publishing.

- Pew Research Center. (2010, 2 24). Millennials: A Portrait of Generation Next. Washington DC.

- Preluat de pe http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/02/24/millennials-confident-connectedopen-to-change/ Prensky, M. (2005/2006). Listen to the Natives (Vol. 63 (4)). Educational Leadership.

- Price, C. (2009). Why Don’t My Students Think I’m Groovy?

- Rodgers, C. (2002). Defining reflection: Another look at John Dewey Teachers College Record (Vol. 104 (4)). Teachers College Record.

- van Roy, R., & Zaman, B. (2016). Why Gamification Fails in Education – And How to Make it Successful. Introducing 9 Gamification Heuristics based on Self-Determination Theory. In Ma, M., & Oikonomou, A. (eds.), Serious Games and Edutainment Applications 2. United Kingdom: Springer-Verlag.

- Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies (Vol. 46 (2)). Management Science.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Simionescu, V., & Mascu, S. (2017). Using Gamification For Teaching Economics In Technical Higher Education: An Exploratory Research. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 532-541). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.65