Abstract

The teaching staff of each school should form a Professional Learning Community (PLC). This concept refers to the focus on the cooperation between members of the organisation in order to achieve the common goals of developing the school (improvement of teaching and learning practices, engaging in joint research, evaluation of results etc.). Everything must start from the existence of a clear and convincing vision of what the organization should become and from the emphasis on a culture of learning for all. This research aimed to present the teachers' perception of these learning communities within schools and the role they fulfill in reality across the organisations. The instrument used in conducting the research was a questionnaire consisting of 30 multiple choice questions administered to teachers from high schools in Bihor county. The results obtained show that most teachers believe that teaching staffs do not always work as learning communities, that more work is still required to make them truly effective, and that the role of school headteachers is essential in this process. The more active, participatory and stimulative is the school leadership, the expected results can be obtained more effectively. The better collective and individual values blend, the more stimulative is teamwork for the individual, the higher performances will be achieved in schools.

Keywords: Professional Learning Communityschoolsteaching staff

1. Introduction

Today, the concept of PLC is used extensively in the area of education. Research conducted in this

field (Dufour, 2004, Hord, 1997, 2004, Kruse, 2010, Cormier& Olivier, 2009, Martin-Kniep, 2004,

Rosenholtz, 1989, Darling-Hammond, 1996, Wood, 2007, Jerome, 2009, Harris&Jones, 2010,

Garmston&Wellman, 1999 etc.) has shown its long term effectiveness in schools, but it has also drawn

attention to the confusion about its definition and approach. Not any group in a school which meets and

discusses constitutes a PLC.

The defining characteristics of a PLC come from the definition of the concept: community,

cooperation, professionalism, learning, change. Summarising the research done so far, some attributes of

a PLC would be: focus on common actions, beliefs and behaviour, commitment for continuing

improvement and development, team effort, but with each member being responsible, the shared

conviction that the teachers' activity is essential for improving the students' learning, develop strategies

which draw on strengths with a view to improve learning, continued evaluation of what has been effective

and of what has been not, taking part in the institution's decision making process.

Thus, in order for a school to function as a PLC, the teachers, supported by the school leadership,

should work together all the time on planning, analysing, implementing, critically examining teaching

activities, focus on the continuous improvement of their performances, on continuing professional

development, share experiences regularly by conducting dialogues and reflecting on problems and

solutions, while promoting new models of thinking and action (Lieberman & Miller, 2008).

In Romania, the existence of PLCs in schools is still in its infancy, and much effort is still needed

to make them indeed effective. There are, however, even though only at a theoretical level in most cases,

PLCs for teachers of certain subject areas, communities that can be organised both at school and local or

even country level. In the Romanian education system, every few months, teachers can take part in

meetings held at municipal, county or national level, where they can express their points of view, share

experiences on a topic decided beforehand. Due to the compulsory aspect of these meetings and to the

topics established by others, not all teachers perceive them as opportunities to learn something new.

These meetings are characterised mainly by analysis and discussions, without clear, applicable outcomes,

which are more or less used by teachers in classroom activities. There are also examples, mainly in the

academic world, of teachers from different cities/areas who share ideas, experiences and chat using the

internet. The existing e-learning platforms make possible video and audio communication, where

interaction is also present. However, in these cases too the interaction is limited to discussions.

A true PLC requires openness. An openness to dialogue, to sharing professional expertise during

experience exchanges based on open dialogue. Continuing review of a teacher's behaviour is the

norm/rule in a PLC (Louis & Kruse, 1995). It is not an evaluative practice, but it is rather based on the

desire for improving teaching activity both at individual and group level, a process based on mutual

respect and trust in the members of the community.

Just like any other school improvement strategy, the quality of designing and implementing the

activity of a PLC will, in general, determine the results obtained. When the meetings are badly prepared,

or when teachers are unable to transform group learning into true changes of the teaching techniques,

PLCs are less likely to succeed. The challenges faced in the process of constructing an effective PLC are

manifold: the headteacher's lack of support could lead to an inadequate investment of time, effort,

resources; meetings held by ill-trained group facilitators could become disorganised and the trust in this

process can decline; a dysfunctional organisational culture could create tensions, conflicts, factions and

other problems, which undermine the potential benefits of PLCs; in case the results, gains are not

quantified, the motivation and enthusiasm for the process can decrease; divergent education

policies/philosophies can lead to disagreements which undermine collegiality and the sense of shared goal

required by a successful PLC.

Our research aimed to show, at empiric level, how well Romanian schools are prepared to become

true PLCs and which are the concerns that should be taken into account when steps are taken to make the

Romanian school be seen as a PLC.

2. Objectives of the research

In this research we proposed to identify the teachers' perception of the collaboration/cooperation

existing in schools, their opinions on the need for continuing professional development, as well as the

extent to which they are involved in the management of their schools and in decision making.

3. Methodology of the research

The sample of research consisted of 186 people (N = 186), all preuniversity teachers from schools in

Bihor county, Romania, with 102 of them from urban schools and 84 from rural ones. Regarding the

years of teaching, 21% belong to the 0-5 years category, 63% to the 5-10 years, 62% to the 10-15 years

and 40% of them have been teaching for more than 15 years. The people of the sample were chosen using

the simple random sampling procedure.

The main research method used was a questionnaire based interview, and the corresponding

instrument consisted of 30 multiple choice questions. The questionnaire was prepared by educationalists

from the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research of Oradea University and each respondent filled in its

printed version. The implementation period was January to June 2016.

4. Results.

The quantitative interpretation of the results was performed by calculating the statistical frequency

of the answers provided by the respondents.

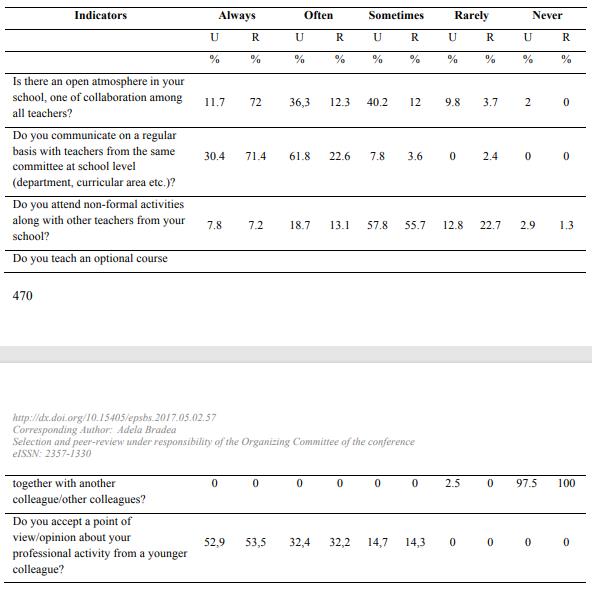

The results are presented in the following tables, where U means “urban”, and R means “rural”.

Table 1 shows that both in urban and rural schools there is collaboration among the teachers. The

statistical differences demonstrate that in rural schools there is constant cooperation (72% of the

respondents chose always). The smaller communities in rural schools are more united and since they

spend most of the breaks together, they are generally better involved in the activities of the school. The

teachers are not divided in specialist committees, there are only one or two teachers who teach the same

subject. It is also good news that in urban school there is cooperation among teachers too, the sum of the

always and often answers being more than that of sometimes – 40.2%. This latter answer, sometimes,

with the highest share, along with the 9.8% of rarely and the 2% of never, shows that in urban schools,

where the teaching staffs are bigger, collaboration and cooperation can face difficulties. On the one hand,

the teachers work in subcommittees (departments, curricular areas etc.) and there is collaboration only

among teachers who teach the same subject. The percentages obtained show this fact. On the other hand,

teachers who do not teach the subjects included in the national evaluation (Romanian language,

Mathematics or subjects related to the students' specialisation area) feel marginalised not only by the

school leadership, but also by their colleagues. However, this aspect cannot be generalised, as it depends

on each teacher's personality to what extent and how they get involved, or not, in the activity of their

school.

The cooperation among teachers does not refer to school activities only, but also to extracurricular

activities, which can develop students' professional and social skills, and which are carried out as joint

activities, as partnerships and projects within and outside the school – activities with an essential role in

strengthening a PLC. The answers given to this item do not show differences between urban and rural

schools. The fact that the biggest share is taken by sometimes – 57.8% - urban, 55.7 - rural – confirms the

fact that this type of activities takes place mostly during the

according to the law, schools must carry out for a week non-formal activities, without being involved in

any other types of activities. This means that teachers are in a way obliged to get involved in non-formal

activities together. Unfortunately, these activities do not always achieve their objectives.

Developing activities which include more learning objectives or results, and which cross the

traditional borders between subjects, are included in the Romanian curriculum as optional subjects, and

they are part of a school based curriculum. This is an opportunity for teachers to collaborate in order to

develop new subjects. Unfortunately, the answer is negative, only a small percentage of teachers, 2.5%,

from urban schools gave the rarely answer. This reality is known to us and we have presented it in details

in other researches (Bradea & Peter, 2014).

Maybe the most important characteristic of a productive PLC is the desire of those involved in it to

accept feedback and of working on improving activity (Louis & Kruse, 1995). The answers given to the

4th item show that, at lip service level, most teachers accept a point of view coming from a younger

colleague – more than 50% of both urban and rural respondents answered always. School teachers should

be in a continuous learning process, in one of professional development, they should collaborate,

exchange experiences in order to support students' learning by promoting new models of thinking and

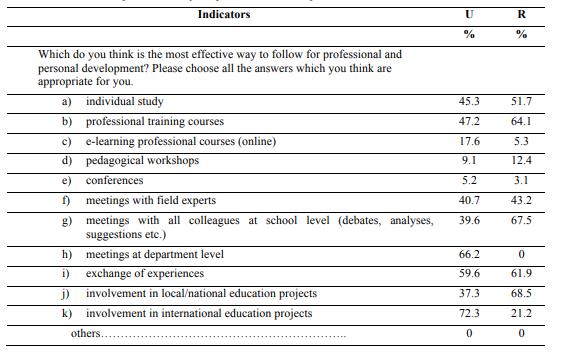

action. Table 2 shows how teachers see the ways that would help achieve that.

The analysis of Table 2 will be done by referring to another item of the questionnaire, in which the

teachers were asked if they were concerned with their professional and personal development. All

respondents gave positive answers. It has been shown that in the case of a PLC teachers should focus on

the continuous improvement of their performances, on continuing professional development, which to a

great extent should take place at the workplace. The results obtained and presented in Table 2 show that a

great share of the answers belong to this type of development (exchange of experiences, meetings with

colleagues at school level, involvement in national projects etc.). Regarding the meetings at department

level, the 0 percentage in rural schools does not conflict with the 67.5% of meetings at school level, but

rather shows a reality: in rural schools there are no departments for different subjects, as in most school

there is only one teacher for each subject.

An aspect which deserves attention is the professional development through pedagogical workshops.

As it has been mentioned early in this paper, in Romania teachers meet, depending on their specialisation,

at municipal, county level every few months, when they form true communities which are intended to be

PLCs. The small percentage of the answers for this form of professional development (d), 9.1% and

12.4% in urban and rural schools respectively, shows their ineffectiveness. The compulsory attendance,

the topics imposed on the participants, the limited applicability of the knowledge acquired in classroom

activities, are all aspects that should give pause for thought to decision makers.

Individual study and professional training courses chosen by each teacher take an important share of

the respondents' answers. It is important, however, that professional development, regardless its form,

results in the creation of teams in which professional dialogues take place, in which professionalism,

expertise, collaboration, learning, change are possible, so that the best decisions can be made in schools in

order to achieve high performance. This assumes an organisational culture in which the school leadership

and the teachers make a team. Then, the way is open for a true PLC.

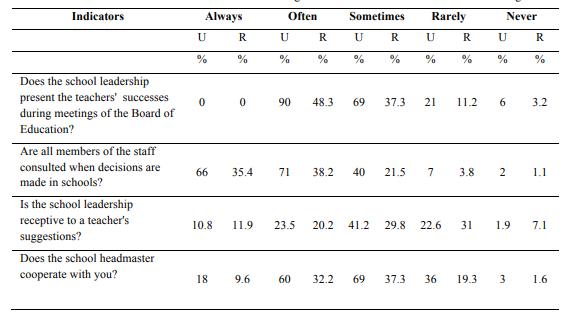

The first item refers to the way in which the leadership of a school collaborates with the teachers by

acknowledging their merits, achievements and by promoting them. It is an essential condition in a school

which claims to be a PLC that the expertise of the staff is capitalised on, even though they do not belong

to the management structure. The answers show that mainly in urban schools (90% - often, 69% -

sometimes) the colleagues' achievements are acknowledged, but, unfortunately, there are also schools

(both urban and rural), in which the leadership is not at all interested in this aspect (6% of the urban and

3.2% of the rural answers were never). It is known that in Romanian schools the executive power lies in

the hands of the Management Board. Those who belong to this body are some teachers chosen by the

entire staff, the deputy headmasters, and the headmaster of the institution. The following items refer to

what extent the school leadership takes into account all its employees' suggestions, and not only those

coming from people have the right to vote when decisions are made. The answers given show the lack of

a participative management. In most cases the school leadership only gives teachers the impression that

they are consulted (66% - U, 35.4% - R – always), as this percentage drops dramatically when they are

asked about whether their suggestions are taken into consideration (10.8% - U, 11.9% - R – always,

22.6% - U, 31% - R – rarely). The answer given to the last item supports somewhat this fact: most of the

respondents claim that the headmaster collaborates with them most of the time. Unfortunately, in order to

be a PLC this is not enough, as long as they are not actively involved in the institution's operational plan.

5. Conclusions

Our research demonstrates that the Romanian schools still need to make the effort to become true

PLCs, to discover the common space in which people should work together to identify what are their

specific needs and what are the lines of efficiency and effectiveness in their professional activity. The

aspects that should be taken into account refer both to the effort of the teachers and to that of those

involved in the institution's management.

Each school has its own distinctiveness, and depending on that, some subject areas tend to

naturally benefit from priority over others, an aspect present in other countries as well (Riley & Stoll,

2004). This is the case, for instance, with subjects included in the national evaluation. The teachers who

do not teach these subjects feel less involved in the life of their schools and less appreciated. The joint

activities organised for and carried out with teams including different subject area teachers, or

encouraging the teaching of cross-curricular optional subjects, foster the development of transversal

competences needed both by students and teachers, but most importantly they contribute to a better

quality education and to defining the identity of the school within the community.

Another aspect worth taking into account is the way teacher evaluation is performed in Romania

(Blândul, 2010). The evaluation criteria include only individual results, without any quantification of

common results, the involvement in the school's life by providing expertise, experience exchanges, the

role of an educator in the implementation of the school's operational plan. Staff reductions are approved

based on this individual evaluation. Sometimes, this makes teachers selfish, egotistic, join professional

training courses without informing their colleagues, because in this way they will get higher evaluation

scores. Such practices have no place in a PLC.

As it has already been said, the proper development of a school assumes an effort of willingness

from those involved, but also a managerial option. Although invested with the same social roles, schools

operate in different communities, their levels of development depend on the resources of the

communities, on the type of management chosen by the school leadership, but also on the needs of those

who benefit of the education services: children, families, adults etc. A well-developed school is one

which meets adequately as large a range as possible of its beneficiaries' needs, is willing to take part and

is actually involved in partnerships, is flexible and benefits of a well-trained and motivated staff (Bradea,

2013).

The more active, participatory and stimulative is the school leadership, the expected results can be

obtained more effectively. The better collective and individual values blend, the more stimulative is

teamwork for the individual, the higher performances will be achieved in schools. According to this

organisational culture each one depends on the other, working together to achieve a common goal. If the

power is centralised, and the manager is oriented towards power and control, it is hard to talk about a

PLC.

If we talk about an organisational culture oriented towards the individual, in which professional

qualities and competences matter more than the status in the institution's hierarchy, then this thing is

possible. Because making full use of the individuals' potential is one of the fundamental values of a PLC.

It is a team culture which builds an interaction between collective values (such as cooperation,

identification with the objectives of the organisation, teamwork, collective mobilisation) and individual

values (appreciation of the individual, individual autonomy and freedom). The leadership should be

flexible and stimulative, based on values like trust in people, in their creative capabilities and self-control.

This research has shown that there are such values in schools. With greater or smaller efforts the

Romanian schools can be transformed in true PLCs. Let's hope in this!

References

- Blândul, V. (2010). Teoria şi practica evaluării. Oradea: Editura Universităţii din Oradea.

- Bradea, A. (2013). The school – from educational services distributor to learning community. Practice and Theory in Systems of Education, 8 (2), 185-191.

- Bradea, A. Peter, K. (2014). The role of optional disciplines in developing transferable competences: A case of Romania. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 62, 21–28.

- Cormier, R. & Olivier, D.F. (2009). Professional Learning Committees: Characteristics, Principals, and Teachers, Annual Meeting of the Louisiana Education Research Association Lafayette, Louisiana.

- Retrieved 25/07/2016, from http://ullresearch.pbworks.com/f/Cormier_ULL_PLC_Characteristics_Principals_Teachers.pdf Darling-Hammond, L. (1996). The quiet revolution: Rethinking teacher development. Educational Leadership, 53(6), 4-10. Retrieved 25/07/2016, from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/mar96/vol53/num06/The-Quiet-Revolution@-Rethinking-Teacher-Development.aspx DuFour, R.(2004). What Is a Professional Learning Community?. Educational Leadership, 61(8), 6-11.

- Retrieved 25/07/2016, from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educationalleadership/may04/vol61/num08/What-Is-a-Professional-Learning-Community%C2%A2.aspx Garmston, R. J., & Wellman, B. M. (1999). The adaptive school: A sourcebook for developing collaborative groups. Norwood, MA: Christopher-Gordon Publishers.

- Harris, A. & Jones, M. (2010). Professional learning communities and system improvement. Improving Schools, 13 (2), 172-181. doi: 10.1177/1365480210376487.

- Hord, S. M. (1997). Professional learning communities: What are they and why are they important?

- Issues ...about Change, 6 (1), Retrieved 24/06/2016, from http://www.sedl.org/change/issues/issues61.html Hord, S.M. (Ed.). (2004). Learning together, leading together: Changing schools through professional learning communities. New York: Teachers College Press & NSDC.

- Jerome, C. (2009). Holding the Reins of the Professional Learning Community: Eight Themes from Research on Principals' Perceptions of Professional Learning Communities. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 90, 1-22, Retrieved 24/07/2016, from https://www.umanitoba.ca/publications/cjeap/pdf_files/cranston.pdf Kruse, S.D. (2010). 5 ways principals can build a climate of collaboration with staff, teachers, and parents. The Leader’s Edge. Retrieved 30/06/2016, from http://www.aasa.org/content.aspx?id=12512 Lieberman, A. & Miller, L. (Eds.) (2008). Teachers in professional communities: Improving teaching and learning. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Louis, K.S. & Kruse, S.D. (1995). Professionalism and community: Perspectives on reforming urban schools. Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin Press.

- Martin-Kniep, G.O. (2004). Developing learning communities through teacher expertise. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Norwood, J. (2007). Professional Learning Communities to Increase Student Achievement. Essays in Education, 20, 33-42.

- Riley, K., & Stoll, L. (2004). Inside-out and outside-in: Why schools need to think about communities in new ways. Education Review, 18(1), 34-41.

- Rosenholtz, S. (1989). Teacher's workplace: The social organization of schools. New York: Longman.

- Wood, D.R. (2007). Professional Learning Communities: Teachers, Knowledge, and Knowing. Theory Into Practice, 46 (4), 281-290. doi:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Bradea, A. (2017). The Role Of Professional Learning Community In Schools. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 468-475). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.57