Abstract

There are scholar opinions warning that both quantitative and qualitative methodologies share strengths and weaknesses when applied to academic learning research (

Keywords: Photovoicenarrative-photovoicelearning patternseducation research

1.Introduction

‘Seeing is a great deal more than believing these days’, states Nicholas Mirzoeff in the beginning of

his work An Introduction to Visual Culture (2009). The fascination for visual information strengths the

intention of the article to shed light on the use of visual methodologies, specifically the photovoice

method, to research academic learning. Photovoice methodologies (PVM) emerged from the fields of

health and community research to become a vital tool due to accuracy in gathering data (Graziano, 2004).

Since its inception in the early 90s, PVM has gained in popularity (Sutton-Brown, 2014, p. 169). In spite

of this fact, the association of PVM with the ‘soft’ area of learning studies is rare and poorly explored by

the scientific literature and research studies in the field. In photovoice, members of a target community

apply specific photographic techniques to document and capture representative experiences of their

individual and collective life.

The purpose of this article is to broad the use of PVM into the field of education and learning

research. The key argument for this initiative of moving from challenged groups to challenging processes

is twofold. First, although there is a significant amount of research on learning, the diversity and

complexity of the process at individual level keeps it on research agendas, especially in the context of

new generations facing serious learning difficulties in the context of learning experiences provided by

contemporary schools and schooling. Second, the recent tendencies in learning conceptualization (e.g.

authentic learning), as in the works of Herrington and Oliver (2000), Slavkin (2004), Rule (2006),

Herrington and Herrington (2006), Lombardi (2007) and others, make an argument for a deeper

understanding of learning as a lived experience and the author believes that PVM can really contribute. In

my work on learning patterns, I drawn from these works in attempt to move to a deeper understanding of

complex and subjective learning experiences.

In the subsequent sections, the article unfolds a discussion on the unique attributes and benefits of

photovoice as a research method and continues by approaching a particular research on learning patterns.

2.Uniqueness of PVM Reframed in a Learning Research Context

2.1. Photovoice Methodology: Essential Features and Theoretical Background

Photovoice is an action-research method initiated by Wang and Burris (1994; 1997) in their work

with in-risk women. In PVM, the participants are provided with disposable cameras to identify,

document, and represent strengths, weaknesses, and concerns of their community (Sutton-Brown, 2014,

p. 169) from an inner perspective. Since its inception, PVM has increased its popularity and has been

applied to disciplines like psychology (Brunsden & Goatcher, 2007), education (Hernandez, Shabazian, &

McGrath, 2014; Mulder & Dull, 2014; Stroud, 2014), nursing (Burke & Evans, 2011; Leipert &

Anderson, 2012), parenting, refugees, and other marginalized groups (Barlow & Hurlock, 2013;

Simmonds, Roux, & Ter Avest, 2015).

An important observation to be made is that PVM gains credit to become a pedagogical tool

(Hernandez, Shabazian, & McGrath, 2014; Mulder & Dull, 2014; Popa & Stan, 2013; Stroud, 2014).

Leipert and Anderson (2012) directed nursing students to take photographs that expressed the perceived

challenges and facilitators of rural nursing practice. Zenkov and Harmon (2009) incorporated photovoice

within a curriculum designed to enhance the writing process for urban youth. Cook and Buck (2010)

found that photovoice provided reflective means of expression for the middle school students who

participated in a water research project.

A corpus of essential features define photovoice methodologies. First, the subjects participating in

research capture in situ their experiences (Hernandez, Shabazian, & McGrath, 2014; (Simmonds, Roux,

& Ter Avest, 2015). Thus, the researcher gains access to an inner perspective of a social or individual

phenomenon. Second, in PVM, the focus is on everyday life experiences. By doing so, the subjects reveal

both objective (e.g. facts, events) and subjective (e.g. emotions, feelings) aspects of their lives.

Finally, photovoice methodologies involve more than taking pictures and talking about them

(Simmonds, Roux, & Ter Avest, 2015). PVM stimulates reflection. In relation to learning, reflection and

metacognitive learning can be stimulated through appropriate erotetic techniques. In addition, PVM is a

relational methodology. Newbury and Hoskins argue that ‘the value of developing relationships with

participants in qualitative research has been widely discussed and effectively demonstrated’ (2010, p.

643).

2.2. Benefits to Promote PVM in Learning Research

In spite of PVM accuracy in gathering data (Graziano, 2004), it has not been widely applied in

education and learning research. This section aims to depict key methodological advantages to support

the extensive use of PVM in education. First, PVM focus is on subjects and their lived experiences.

Second, applying PVM facilitates the ‘in-the-moment’ investigation of social and individual phenomena.

Third, PVM offers support for intensive longitudinal studies. Finally, the subjects become co-researchers

and actively contribute to data analysis.

2.2.1.Access to Settings and Subjective Experiences

In PVM research, subjects are asked to take pictures during classes, individual study time, or

collaborative work. This approach provides access to individual experiences that are hardly graspable or

even unreachable for the researcher. To counter argue, one cay say that observational research may give

access to similar experiences. As for learning and learning patterns research, I disavow this alternative.

The interference of researcher may cause essential changes in processing strategies or in regulation

strategies (Richardson, 2013). For instance, a set of pictures taken by the participants described learning

activities taking place during late night. In such a situation, the researcher cannot be present due to ethical

considerations.

When researching learning, one may be interested in processes of which subjects may not be

aware of. Richardson (2013) suggested the idea of rejection of students’ opinions on learning. He argued

their accounts focus on particular social interactions that they usually called ‘learning’. These may vary

across universities. Therefore, applying PVM on under-acknowledged research participants had a number

of benefits in learning investigation. Hernandez and colleagues (2014) used photovoice to examine

parallel learning processes of college students and preschool children. According to the authors, PVM

allows young children to visually represent their thoughts and abilities while their abstract thought

processes are still in their formative years (Hernandez et al., 2014, p. 1948). For those young children, the

photovoice methodology was adapted due to limited abilities of subjects to take photographs. Initially, the

teacher started a debate. Based on that, the subjects were provided with paper and pencils to draw and

reflect on discussion. Follow-up questions based on pre-determined prompt were asked.

2.2.2.Investigation of Immediacy

By assessing subjects’ learning experiences ‘in-the-moment’, PVM clearly contributes to reduce

bias that may appear in retrospective self-report research. Thus, PVM strengthens researcher’s proximity

to subjects’ lives. The photographs document behavioral experiences of participants. Blending PVM with

ESM and narrative techniques sustains the reflection of cognitive and emotional events in subjects.

2.2.3. Support to Intensive Qualitative Studies

Scientific literature on PVM usually defines this approach as a participatory research method

providing visual data and descriptive information. PVM supports descriptive studies to explore the daily

experience of learning, for instance.

As described in a previous section, PVM studies were employed to research parallel learning in

college students and preschool children (Hernandez, Shabazian, & McGrath, 2014). Recent research

studies tend to apply photovoice as both a research and pedagogical tool (Cook & Buck, 2010; Harkness

& Stallworth, 2013; Hidalgo, 2015; Stroud, 2014). Mulder and Dull (2014) present a descriptive research

to facilitate and assess self-reflection in master students and faculty staff through photovoice. As the

authors underline, photovoice may have an additional advantage to help socialize students during classes

and collaborative work. Harkness and Stallworth (2013) applied PVM to explore and understand high

school females’ conceptions of mathematics and learning mathematics. The cited study investigated high

school girls who reported learning difficulties in mathematics. The study contributed to the understanding

of how each participant knew mathematics and revealed epistemic profiles: received knowers and fragile

subjective knowers (Harkness & Stallworth, 2013, p. 343).

2.2.4.Engaging Subjects in Data Analysis

Photovoice offers an opportunity for participants to engage actively in the research process of their

own learning experiences. Both the researchers and participants can benefit from this participatory

approach. Empowering the participants can result in personal abilities to critically observe and reflect on

learning behaviors and their effectiveness. Blackman and Fairy (2007) argue PVM participants may learn

skills in critical thinking and analysis. Therefore, PVM contributes to a better understanding of how

context and information influence learning activities and outcomes. For instance, some of the participants

expressed their considerations and concerns about the time they spend on preparing learning (e.g. students

color and underline important sequences in course materials).

3.Case in Point: Photovoice to Research Learning Patterns

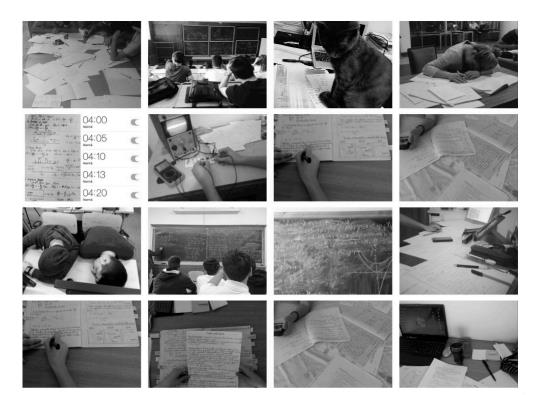

In the context of this study, the author applied photovoice to document the subjective experience

of academic learning in relation to learning strategies. Undergraduate students captured and presented

their learning experiences by using photograph elicitation and narrative techniques. Photographs depicted

individual and collective learning experiences in different settings: classrooms, libraries, and individual

study. The selection of learning experiences was twofold: based on researchers prompts, and based on

students’ choice. To support learning inquiry, the authors coupled PVM with experience sampling

methodologies (ESM). At the end of data collection process, the pictures were analyzed and made the

object of collective analysis during group interviews. The participatory phase of data analysis was

followed by content analysis conducted by the author.

3.1. Conceptualization of PVM in a Study on Learning Patterns

Three conceptual and methodological approaches were blended to support the investigation of

learning patterns in higher education: photo-narratives, experience sampling methodologies (ESM), and

interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA).

Photo-narratives are also known as poster-narratives (Simmonds, Roux, & Ter Avest, 2015, p. 37).

Specifically, the subjects involved in taking pictures select a set of representative pictures and display

them on a board. The poster is accompanied by an oral presentation.

As Zirkel, Garcia, and Murphy (2015, p. 1) argue, ESM ‘examine individuals’ experiences in the

context’. The particular feature of ESM is the ‘ecological’ assessment of experiences, behaviors,

thoughts, and feelings at the moment they happen on repeated time occasions (days or weeks). Zirkel and

her collaborators (2015) identify key-methodological aspects to promote ESM in educational research. In

relation to photovoice, investigation of immediacy and access to subjective experiences appear to be more

relevant. Fisher and To (2012) suggest that ESM approaches contribute to reducing bias. When applying

ESM, an important decision to make is related to choosing the appropriate way to sample experiences.

Three primary means are usually discussed (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013): (1) random sampling; (2) fixed

sampling, and (3) event-based sampling. In random sampling, the researchers usually uses mobile phone

alerts to indicate randomly the moment when the subjects will complete a brief survey or take a photo (in

the case of PVM). Fixed sampling refers to studies in which the moments or intervals to collect thoughts

or feelings have been apriorically set. Finally, in event-based sampling, researchers may set data

collection to occur in response to particular events (Zirkel, Garcia, & Murphy, 2015, p. 6).

In this particular study, photovoice was applied as narrative-photovoice (Simmonds, Roux, & Ter

Avest, 2015) in an intensive longitudinal design. Narrative-photovoice draws on constituencies of

photovoice and photo-narratives, but is underpinned explicitly by narrative inquiry theory. Therefore, the

participants reveal what is displayed in their photographs in the form of narrative (Simmonds, Roux, &

Ter Avest, 2015, p. 37).

A ten-weeks research framework was designed. Continuously, the participants built an on-line

collection of pictures and associated narratives to describe each of them. The narratives were based on a

structured scaffolding entailing four questions: (1) Where this picture was taken; (2) What are you doing

in this picture? (3) What do you think about the situation; (4) How do you feel. Writing the narratives

defines a stage of a deeper reflection on learning strategies. The narratives are ways to create and imbue

meaning about the way learning occurs and one adapts his or her learning behaviors to different contexts

and persons. Thinking and writing on what occurs when learning takes place activate, renew, and

complete metacognitive knowledge about persons, strategies, and tasks. The researcher recommendations

went on writing narratives contiguously to keep the point-in-time specific of the methodology. To upload

pictures and write narratives, the students used Survey Gizmo® online data collection platform.

In order to strength the participatory of the PVM methodology, IPA was considered a suitable

approach. The aim of interpretative phenomenological analysis is to explore in detail how participants are

making sense of their personal and social world (Lonka & Makinen, 2004). In our research, we were

interested in learning experiences of students in higher education. IPA blends the participation of research

subjects with that of the researchers engaging both in analytical approaches. Smith, Flowers and Larkin

(2009, p. 78) state that the existing literature on analysis in IPA is not convergent on a single ‘method’ for

working with data. The focus of IPA is on participants attempt to make sense of their experience (Smith

et al., 2009). To apply IPA, various complementary strategies can be put in place.

3.2.Steps in Photovoice Method

For the research study conducted, photovoice involved four distinct stages, as Sutton-Brown

(2014, p. 171) suggests: (1) recruiting participants; (2) initial group meetings; (3) taking pictures; (4)

meetings with subjects to discuss and analyze the pictures.

3.2.1.Recruiting Participants

During this phase, undergraduate students from three regular universities were attracted and

selected to contribute in the process of data collection and analysis. The photovoice participants hold the

responsibility of creating the photographs that will eventually become the object of further discussions

and analysis.

Because of the participatory nature of the PVM, the recruitment process is capital in order to

support authentic dialogue between researchers and participants. The participants in our research reflect a

purposive sampling selection based on conventional means (flyers, posters, and on-line ads). The

selection followed to accomplish the goal of recruiting a heterogeneous group in order to provide a

broader perspective on learning patterns. The heterogeneity was appreciated from the perspective of

students’ field of study, including science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM disciplines),

socio-humanities, and economics. Forty-nine students ageing in range from nineteen to twenty-three years

(M_age=21,7) were chosen from a pool of eighty-seven subjects to participate in our photovoice project.

Twelve of them (eight females and four males) abandoned the project. The participation was voluntary

and the subjects were able to discontinue at any time throughout the project. At the end of the project, the

participants received financial incentives.

3.2.2.Initial Group Meetings

Wang and Burris (1994; 1997) support the need of initial group meetings to discuss theoretical,

practical, and ethical aspects of PVM and ESM. A primary role of these meetings is to learn more about

photovoice and to give a prompt to guide the selection of experiences to be documented. During the

preliminary group meetings, the subjects were familiarized with the process of data collection and

procedural ethics in photovoice. A prompt to guide the selection of events to be captured was adopted:

‘Take photographs of objects, people (including yourself), situations anywhere in your faculty and home

environment able to describe the way you learn and what learning means to you’. After the initial

meetings, the participants signed a written informed consent.

3.2.3. PVM in Action: Data Collection

The success of a photovoice project depends on a number of factors such as the nature of the

investigated phenomenon, the period, and the availability of participants to take photos (Sutton-Brown,

2014, p. 175).

The participants were provided with a time frame to take photos, upload them by using the Survey

Gizmo platform, and write narratives. The subjects used their own mobile phones to take pictures.

Random and event-based sampling were considered suitable approaches. The author guided random

sampling procedures. For example, the subjects received a text message in the morning saying to capture

learning experiences or situations from that specific day at the faculty or in individual study settings. The

participants were responsible for even-based sampling. Thus, they were encouraged to take pictures

whenever they feel they experience a relevant situation to describe academic learning.

This stage resulted in a great number of pictures (692 and the corresponding narratives) to be

discussed and analyzed during the next stage of the project.

3.2.4.Data Analysis

In traditional research methodologies, data collection and analysis are distinct parts of the

research. In participatory research and in PVM, the borders between them are less obvious.

Both the researcher and the participants contributed to the analysis process. The subjects were

invited to participate to focus groups to discuss and analyze the pictures. A number of nine focus groups

were conducted. In the beginning of the discussion, a set of ten pictures were selected by the participants

according to individual and collective relevance criterion. To ignite the discussion the SHOWeD

technique was applied (Wang, 1999). SHOWeD is an acronym of the questions to be asked: What do you

See here? What is really Happening? How does this relate to Our lives? Why does this problem or

strength exist? What can we Do about it? The technique sparks critical thinking. The focus groups were

typed and transcribed. IPA was performed. A first step refers to reading and re-reading the data (interview

transcripts and narratives) based on a line-by-line analysis of the participants’ meanings and

understandings of their lived experiences. The second consisted in applying the noting strategy.

After re-reading the transcriptions, the researcher marked relevant quotes of participants. To

facilitate the identification of the emergent learning patterns, I associated comments to the identified

quotes. In the third step, I grouped the quotes and comments according to their conceptual and

experiential convergence. Six themes were revealed (processing strategies, conceptions of learning, and

orientations to learning, regulation strategies, positive emotions, and negative emotions). Those entail

twenty-one categories (the corresponding learning components and achievement emotions, according to

the learning pattern model – see Vermunt (1996), Vermunt & Vermetten (2004) and Gibels, Richardson,

Donche, and Vermunt (2014). for a more detailed discussion on this subject matter). In the last step, the

emergent themes were gathered in clusters according to the model of learning patterns (Gibels et al.,

2014, p. 15). Exploratory comments were associated with quotes and themes.

4.Conclusions

The present paper aimed to empower the use of photovoice in education research. With the

exception of studies focusing on nursing, health, and education of vulnerable populations, PVM has not

been widely harnessed in education and learning research.

Theoretical and methodological aspects were discussed. The article argued that PVM could be

enriched by using experience sampling methodologies and interpretative phenomenological analysis. A

corpus of benefits is a pivotal argument to support the integration of PVM in education and learning

research. Summarizing, PVM emphasize the subjective contribution of participants and gives them the

opportunity to become co-researchers. Intensive longitudinal studies can be designed based on PVM.

Drawing upon a study conducted by the author, a framework to apply PVM was proposed and discussed.

In summary, photovoice is a participatory research method effective in assisting subjects to

document real experiences in learning, increasing critical and reflective skills. Through PVM, the goal of

empowering participants is achieved. The use of PVM in educational research contexts was not extensive,

but proved utility and reliability.

Acknowledgements

The research project presented in this paper was funded by Young Researchers Excellence Fellowships 2015 Competition - Project financed by the University of Bucharest Research Institute (ICUB).

References

- Barlow, C. A., & Hurlock, D. (2013). Group Meeting Dynamics in a Community-Based Participatory

- Research Photovoice Project with Exited Sex Trade Workers. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 12, 132-151.

- Bolger, N., & Laurenceau, J.-P. (2013). Intensive Longitudinal Research Methods: An Introduction to Diary an Experience-Sampling Research. New York: Guilford Press.

- Brunsden, V., & Goatcher, J. (2007). Reconfiguring Photovoice for Psychological Research. The Irish Journal of Psychology, 28(1-2), 43-52.

- Burke, D., & Evans, J. (2011). Embracing the Creative: The Role of Photo Novella in Qualitative Nursing Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 10(2), 164-177.

- Cook, K., & Buck, G. (2010). Photovoice: A Community-based Socioscientific Pedagogical Tool.

- Science Scope, 33(7), 35-39.

- Fisher, C. D., & To, M. L. (2012). Using experience sampling methodology in organizational behavior.

- Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(7), 865-877.

- Gibels, D., Richardson, J., Donche, V., & Vermunt, J. (Eds.). (2014). Learning Patterns in Higher

- Education. Dimensions and Research Perspectives. New York: Routledge.

- Graziano, K. (2004). Oppression and Resiliency in a Post-apartheid South Africa: Unheard Voices of

- Black Gay Men and Lesbians. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 10(3), 302-316.

- Harkness, S. S., & Stallworth, J. (2013). Photovoice: Understanding High School Females' Conceptions

- of Mathematics and Learning Mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 84(3), 329-377.

- Hernandez, K., Shabazian, A. N., & McGrath, C. (2014). Photovoice as a Pedagogical Tool: Examining the Parallel Learning Processes of College Students and Preschool Children through Service Learning. Creative Education, 5, 1947-1957.

- Herrington, A., & Herrington, J. (2006). What is an Authentic Learning Environment? In A. Herrington, & J. Herrington (Eds.), Authentic Learning Environments in Higher Education (pp. 1-13).

- Hershey, PA: Information Science Publishing.

- Herrington, J., & Oliver, R. (2000). An Instructional Design Framework for Authentic Learning Environments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 43(3), 23-48.

- Hidalgo, L. (2015). Augmented Fotonovelas: Creating New Media as Pedagogical and Social Justice Tools. Qualitative Inquiry, 21(3), 300-314.

- Leipert, B., & Anderson, E. (2012). Rural Nursing Education: A Photovoice Perspective. Rural Remote Health, 12(2061), 1-11.

- Lombardi, M. M. (2007). Authentic Learning for the 21st Century: An Overview. ELI Report No. 1. Boulder. CO: EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative.

- Lonka, K., Olkinuora, E., & Mäkinen, J. (2004). Aspects and Prospects of Measuring Studying and Learning in Higher Education. Educational Psychology Review, 16, 301-323.

- Mulder, C., & Dull, A. (2014). Facilitating Self-Reflection: The Integration of Photovoice in Graduate Social Work Education. Social Work Education, 33(8), 1017–1036.

- Newbury, J., & Hoskins, M. (2010). Relational Inquiry: Generating New Knowledge With Adolescent Girls Who Use Crystal Meth. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(8), 642–650.

- Popa, N. L., & Stan, L. (2013). Investigating Learning Space with Photography in Early Childhood Education: A Participatory Research Approach. Revista de cercetare și intervenție socială, 42, 248-261.

- Richardson, J. T. (2000). Researching student learning: Approaches to studying in campus-based and distance education. Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press.

- Richardson, J. T. (2013). Research issues in evaluating learning pattern development in higher education. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 39, 66-70.

- Rule, A. C. (2006). Editorial: The Components of Authentic Learning. Journal of Authentic Learning, 3(1), 1-10.

- Simmonds, S., Roux, C., & Ter Avest, I. (2015). Blurring the Boundaries Between Photovoice and Narrative Inquiry: A Narrative-Photovoice Methodology for Gender-Based Research.

- International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14(3), 33-49.

- Slavkin, M. L. (2004). Authentic Learning: How Learning about the Brain Can Shape the Development of Students. Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Smith, J. A., & Osborn, M. (2007). Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. In J. A. Smith, Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods (pp. 53-80). London: Sage.

- Smith, J. A., Paul, F., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Theory, Method and Research. London: SAGE Publications.

- Stroud, M. W. (2014). Photovoice as a Pedagogical Tool: Student Engagement in Undergraduate Introductory Chemistry for Nonscience Majors. Journal of College Science Teaching, 43(5), 98-107.

- Sutton-Brown, C. A. (2014). Photovoice: A Methodological Guide. Photography and Culture, 7(2), 169-185.

- Vermunt, J. D. (1996). Metacognitive, Cognitive and Affective Aspects of Learning Styles and Strategies.

- A Phenomenographic Analysis. Higher Education, 31, 25-50.

- Vermunt, J., & Vermetten, Y. (2004). Patterns in student learnining: Relationships between learning strategies, conceptions of learning and learning orientations. Educational Psychology Review, 16, 359-384.

- Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1994). Empowerment through Photo Novella: Portraits of Participation. Health Education Quarterly, 21(2), 171-186.

- Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. Health Education and Behavior, 24(3), 369–387.

- Zenkov, K., & Harmon, J. (2009). Picturing a Writing Process: PhotoVoice and Teaching Writing to Urban Youth. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 52(7), 575-584.

- Zirkel, S., Garcia, J., & Murphy , M. (2015). Experience-Sampling Research Methods and Their Potential for Education Research. Educational Researcher, 44(1), 7-16.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Manasia, L. (2017). From Community to Individual. Re-Thinking Photovoice Methodology for Education Research. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 450-459). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.55