Abstract

In this paper we answer the question: How do MA-Students and Postgraduates in the field of Adult Education consider the added value of internationality for their professionalization? More and more the pedagogical qualification needs to incorporate a wider, international dimension, in the interconnected world. A lot of effort is done by the European Union and the member states, to reach a European dimension in the academic qualification of their professionals. The opinion of the students qualifying as professionals in adult education helps to identify the effects of such effort. Studying with an international dimension, partly in a foreign language, to gain international competences needs a lot of motivation. In our exploration we find some plausible explanations – related to the labor market, to the personal development, the interest in intercultural communication, the widening of the horizon and the building up of international networks. We summarize with recommendations on how these views of the students can be used for a further development of international aspects in the study programs

Keywords: Intercultural competenceinternational study programadult educationprofessionalization

1.Introduction: Facets of Internationalization in Higher Education

Internationalization of the curriculum in higher education institutions (HEIs) is nowadays a

common reality. It can take very different shapes, and it can be introduced with various extensions,

ranging from the micro-level design of the course concept (i.e. comparing with similar course concepts

offered in other universities; using foreign scientific literature, proposing dedicated indicators for

evaluation comprising comparative research or of describing the international state of discussion on the

topic etc.), till student/ staff mobility, or more complex ways of cross-border curriculum, joint degree

programs, international campuses (European Commission, 2015, Knight, 2013, Gregersen-Hermans,

2015, Guri-Rosenblit, 2015), comprising the whole university strategy and actions, or dedicated measures

and targets at national system level, or transnational bodies/networks (European Commission, 2015,

Beleen, Elspeth2015, Williams, 2016).

The increased emphasis on internationalization of higher education is driven by the general believe

that mobility and internationalisation “pave the way to the creation of a society where everyone can live

peacefully, and assist in promoting democratic values, meeting the challenges of the globalized labor

market” (Palomares, Pietkiewicz 2015). By knowledge sharing, mutual understanding staff and students

get an increased awareness about the challenges of global society, widening their horizons, and are better

prepared to meet such challenges, to live and work in different contexts. Also, internationalization, as one

of the main layers of changes in universities, contributed to an increased quality of teaching and learning,

and of university services, an easier integration and adaptation of know-how and good practices, and

fostered generally innovation into academic activity, such impact being highlighted by teachers, students,

management staff of HEIs in the different monitoring and evaluation studies (Erasmus Impact Study,

2014, Lodge, Bonsanquet, 2014, Sursock, 2015).

The approaches of universities towards internationalization become more systematic and coherent,

as nowadays they set up their strategy for internationalization, and evaluate its impact at the institutional

level, due to the concern both of the management of the institution, or as the demand of the national or

European monitoring bodies. The evaluation study carried out by European University Association in

2013 underlines such trend, highlighting the main priorities of universities having such strategies. The top

priorities listed in EuropeanUniversity Association (2013) as first option by universities in their strategies

are: attracting students from abroad, internationalizing teaching and learning, and providing more

opportunities for students to have learning experiences abroad.

The quality of international activities is to top the quantitative focus of number of students

attracted, or number of partnerships set etc., as universities struggles for increased reputation and better

places in university ranking, for improving the quality and diversity of curricula, research and services

through international partnerships, for developing wide scientific communities able to keep up with the

speed of knowledge development (Lodge, Bonsanquet, 2014, Sursock, 2015, European Commission,

2015, Guri-Rosenblit, 2015, Gregersen-Hermans, 2015). Mainly the research advanced universities,

aiming to the desiderata of world class universities, able to act as important actors in the global society,

have a more differentiated approach to the internationalization of their activities.

Various contexts of internationalization can act together, and in the same HEI, or even faculty,

department, study program can be met all range of internationalization activities, depending on purposes

for internationalization, people and resources involved, infrastructure etc. Irrespective we talk about

visiting scholars, guest lectures and/or mobile students, or about different ways of designing and running

the study programs: for instance as twinning, franchise, double/ joint or about integrating parts of the

activities demanded to the students to undertake with the aim of developing the international view and

competences (ex. by undertaking transnational projects integrated in the study programs or international

case studies, internships and practices in other research centres or companies abroad, about collecting

study credits from other universities or attending courses, in online or blended format at other

(partner)universities etc.), or we aim to extend our programs to an international market, to other countries,

enrolling students from abroad by opening branch campus, virtual offers, or we are part of international

consortia of universities developing joint programs or research networks (accompanying, for instance, the

doctoral schools), or we develop any other possible didactic experience with international dimension for

our students (Knight, 2013, Hoare, 2013, Soria, Troisi, 2014, Beleen, Elspeth, 2015, EC 2015, Guri-

Rosenblit, 2015), clear vision, targets, commitments, strategic integrate actions are needed. Such diversity

of internationalization of the curriculum and its delivery is described by a variety of concepts:

internationalization at home, cross-border curriculum, joint programs, transnational projects etc.

(Waterval, Frambach, Driessen, Scherpbier, 2015, Knight, 2013, Beelen, Elspeth, 2015, Sawir 2013).

The management issues for setting up and running them vary from the relationships of and

communication with teachers, students, administrative staff, designing and delivering the learning

materials, till the formal aspects of procedures, rules, record keeping, accreditation body and ensuring

comparable educational quality, equivalency of learning outcomes (Waterval, Frambach, Driessen,

Scherpbier, 2015, de Wit, Engel, 2015, Hoare, 2013). Furthermore, in developing more legally relevant

ways of internationalization of the curriculum, like it is the case, for instance, in setting up joint programs

or opening branch campuses, the management issues are becoming quite difficult. As it was underlined in

Waterval, Frambach, Driessen, Scherpbier (2015), mainly when more institutions from different countries

are involved in commonly designing and delivering of the curriculum, the differences occur anyhow, due

to the local contexts, differences in access to resources and support systems, different learning and

teaching cultures, language competences, formal regulations etc, the necessary procedures are very

complex.

Internationalising the curriculum addresses all the students, irrespective their status, in the

interconnected world. Just staying at home, they attend an online course at another university, or they can

attend classes at an international university having a branch in their town, or they can be enrolled in a

joint degree program run by their home university in partnership with other universities, the whole

program or just a Masive Open Online Course (MOOC) / lecture etc. Travelling abroad, with a student

grant, for work, or personal reasons, they add another dimension to their international studies. However,

the number of mobile students abroad is quite low: one in ten students at the master’s or equivalent level

is an international student in OECD countries, rising to one in four at the doctoral level… The master

students are about twice as much as for bachelor’s or equivalent program (OECD, 2016).

Through the technological means of communication and interaction all students are connected to

the wider world and global information, but not necessary in a pedagogically structured way. The

preparedness of students to be aware and understand, to be able to act in an interconnected world has to be

ensured for all students, to reduce the competitive advantage of few privileged mobile students

(Palomares, Pietkiewicz 2015, Lehtomaki, Moate, Posti-Ahokas, 2015, Williams 2016). Such desiderata

mean that the curriculum, that the teaching and learning, the pedagogical practices of both disciplinary

and extra-curricular activities provided in universities should have included the international dimension,

aiming to develop the intercultural competence, with all its dimensions.

Irrespective we talk about promoting mutual understanding, about international awareness,

international competence and international expertise (Sawir, 2013), about critical (self-)awareness, respect

for diverse interpretations of practices and the use of inclusive dialogue, about intercultural sensitivity,

and an international understanding (Perry, Southwell, 2011, Odağ, Wallin, Kedzior, 2016, Foster,

Yaoyuneyong, 2016), as key principles and different levels of developing and understanding the cultural

competence (Trede, Bowles, Bridges, 2013), these different levels of learning outcomes differentiate in

the same time various kinds of curriculum internationalization (Trede, Bowles, Bridges, 2013, Sridharan,

Leitch, Watty, 2015, Yamada 2014, Odağ, Wallin, Kedzior, 2016). Different concepts have been

developed, and different research work was done for measuring the intercultural competences. For

instance, for measuring the intercultural sensitivity (including the affective aspect, the knowledge

dimension of knowing and the behavioral and attitudinal aspect of intercultural competence), the

Intercultural Sensitivity Scale (ISS) has been differentiated using five factors: interaction enjoyment,

respect for cultural differences, interaction confidence, interaction enjoyment and interaction attentiveness

(Perry, Southwell, 2011). The different steps of the scale can be reached by different levels of integrating

into the curriculum the international aspects: “the first level, ‘international awareness’ involves integrating

international perspectives into teaching with the ultimate aim to prepare students who respect differences

and have an international attitude. The second level ‘international competence’ involves engaging with

students from other cultures and through in-depth study of international subject matter. The third level of

the typology, ‘international expertise’ is the immersion of students into the international study, for

example, by studying a foreign language or by living and working in a foreign country. The outcome is to

produce global professionals who can operate anywhere in the world” (Sawir, 2013).

Different researches underline the positive impact on the students’ learning of the international

dimension, like: developing an international mind-set and related to this, a more advanced and an

increased intercultural competence, leading to a better tolerance for ambiguity, behavioral flexibility,

communicative awareness, knowledge discovery, respect for others and empathy (Perry, Southwell, 2011)

and also other general attributes such as self-efficacy, tolerance of ambiguity, critical thinking/creativity,

non-ethno-centric and openness which can be applied in specific cultural contexts where other attributes

such as social, political and cultural knowledge, language ability and specific communication skills are

needed (Trede, Bowles, Bridges, 2014). Equipping graduates this way is a must in a nowadays global

society, as they will be exposed to all kind of intercultural contexts and situations, both in their

professional and personal life. Such need requires an international dimension in the curriculum provided,

both in a formally expressed one and in the hidden one, in the core and the extended one.

Making students more aware of the international dimension of the issues they are going to deal

with in their professional field is a learning outcome needed to be incorporated nowadays in all study

programs. Such learning outcome is to be therefore fostered in all disciplines, and specifically considered

while designing the teaching and learning and assessment settings and tasks (Sridharan, Leitch, Watty,

2015, Yamada, 2014). This requires, however, that the teaching staff master a wide international

understanding and competence in international matters. It is therefore even more important that study

programs aiming to professionalize teaching staff for at all educational levels should have integrated an

international dimension in the offered curriculum. This is true for professionalizing the future adult

educators as well, such need being emphasised both by various diagnosis and prognosis studies (European

Commission, 2013, Milana, Holford, 2015, Research vor Beleid 2008, 2010, Nuissl, Lattke, 2008,

Slowey, Schuetze, 2012, Lattke, Jutte, 2014) and by different researches (Nuissl, Lattke, 2010, Lattke,

Jutte, 2014), even addressing the future profile of competences of adult educators (Bernhardsson, Lattke,

2011, Research voor Beleid, 2010), or the expectations of the stakeholders for increased quality of adult

education (European Commission, 2013, CEDEFOP, 2013), or being highlighted by the adult educators

themselves (Bernhardsson, Lattke 2011, Nuissl, Lattke 2008, Sava, Danciu, 2015).

2.Context of the Study, Methodology

The study highlights the views of the students enrolled in an international master program in adult

education, European Master in Adult Education (EMAE), the largest offer of this kind, provided

European-wide by a consortium of 10 universities, from 9 countries across Europe. The students have also

the possibility to advance to the PhD level through the European doctoral school set within the

consortium, and a lot of them come at MA level from a comparable BA level, having this way the

opportunity to professionalize at advance level, with a European perspective, at all three levels of

academic studies. Such offer was set up within the Erasmus curriculum-development project “European

Studies and Research in Adult Learning and Education” – ESRALE (www.esrale.org), project running

between 2013-2016, but the provision of the EMAE lay back in 2004-2007, celebrating 10 years since

running the master program.

EMAE is offered as Joint Program and students from all partner universities benefit from the

internationalization of their studies in multiple ways, as different resources and support services have been

implemented: mobility of students and staff, both virtual (online courses and lectures) and on campuses,

summer and winter schools, core-curriculum (covering 70 ECTS out of the 120 ECTS of a master

program), transnational project work or study texts published in English. The concept of

internationalization at home (Beleen, Elspeth, 2015) and of cross-border mobility (Knight, 2013), both for

teaching and research, are thus put in place. This way the more than 200 students attending the EMAE are

exposed to the internationalization of their studies (Sawir, 2013), even if they study at home in their

national language.

These students were asked how they perceive the added value of internationality in their studies.

Some of them enrolled to the studies without knowing about the international dimension, as all the

masters are running as national masters, but later on, they have been exposed at all the additional offer.

The masters running for professionalization in adult education are quite small, and not in all

partners’ universities the programs are directly labelled as adult education, but having comparable course

offer.

For the purpose of this paper, we focus on the answers offered by the students from Italy, Serbia,

Hungary, and Romania, all in all answering from these countries 68 students at the online survey carried

out in spring 2016. The countries were chosen because of different experience in running EMAE (Ro and

It since 10 years, Hu and Serbia joining in 2013), and different levels of addressing the study offers. The

online questionnaire comprised 21 questions, addressing, on one hand the motivation for international

studies, but also the perceived outcomes from the student´s point of view, the level of the intercultural

competence (Perry, Southwell, 2011, Sawir, 2013, Trede, Bowles, Bridges, 2013). There were listed also

the different aspects to be addressed by institutions providing the internationalization of the study offers

(de Wit, Engels, 2015), as well as the different benefits of the international study offers (Gregersen-

Hermans, 2015). With two exceptions the questions were closed, the open ones were closed afterwards.

The realization of the sample was different; University of Belgrade, Serbia (UB) represents 16,4

%, University of Florence, Italy (UF) 28, 4 %, Univ. Pecs, Hungary (UP) 14,9 % and the University of the

West from Timisoara, Romania (UVT) 40, 3 % of the answers. Also, the level of the students in the study

program is different: 9 % are on BA – Level, 41,8 % on MA 1. Year, 38.9 % on MA 2. Year and 10,4 %

on PhD level. This differentiation on study levels is possible due to the fact that in Serbia is not yet

introduced the Bologna Process structure (3 years BA, 2 years MA, and 3 years PhD), still having 4 years

BA in adult education, and 1year master program. Also, some universities allow students to pick up

classes at different study levels, according to their interests and needs.

The analysis followed the principles of statistical significance. Due to the little number of the total

we carried out only a few correlations, mainly regarding the facts of international parts of the curriculum

and valuing the situation and relevance of internationalization in regard of the university the students

come from.

3.Findings

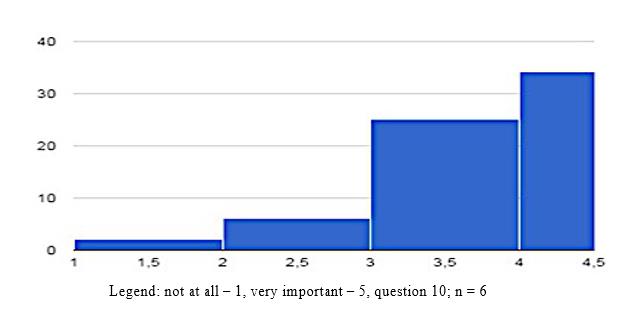

First of all: all students consider the international aspects of their study program as important. The

question was focused on the subject being studied, in this case, the field of adult education, studied in the

curriculum of ESRALE. Four out of five students are appreciating the international elements of their

study program:

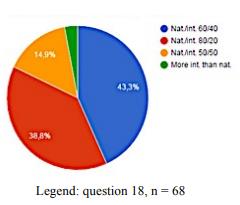

Comparing the given amount of internationality with the wished one, the students want even more,

but in a moderate way. In the existing curricula, the relation between national and international aspects is

perceived as seen in figure

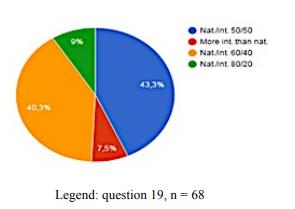

Asking about the wished relation between national and international aspects the picture differs

(figure

extent or even higher international aspects as the national ones, in the wished offer 50,8% of the students

want both approaches with the same amount of offers, workload and topics, and even four out of ten are

asking for a major internationality. The relation wished by the students has more elements of international

topics; only one out of ten students wish a higher share of national studies, whereas half of them.

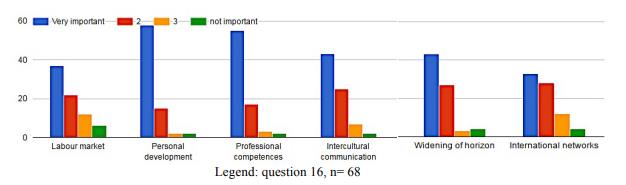

Regarding the motivation for enrolling in a study program with international parts like

EMAE/ESRALE there is a clear focus on individual benefits like widening the horizon and developing

the personality, less on the labour market and work perspectives. Still most important is the choose of the

subject or topic – almost a hundred percent of the students point that out. Also underlined is – in general –

the further professional development (91,3 %), many students want to found their already realized work in

adult education with academic studies. In this direction goes also the motivation of specialization (79,7

%). The two factors linked to internationality are not so strong; the possibility of studying abroad (58 %)

is even more motivating than the internationality of the curriculum as such. For a little bit, less than half

of the students (44 %) the international aspects of the study program were a motivational factor. In this

regard the students vote as follows:

Interesting is the difference being made between labor market motivation (86,76 %) on the one

hand and professional competencies (95,58%), and personal competencies (96,72%) on the other one. Not

the labor market is the point of interest, but a higher level of competence – this fits the currently raising

importance of outcome orientation of learning and to the strong role of competence in the motivational

factors in general. At the same time, it is mirroring the current relevance of internationality in the practice

of adult education. In this field mainly the intercultural competence is important as part of professional

work.

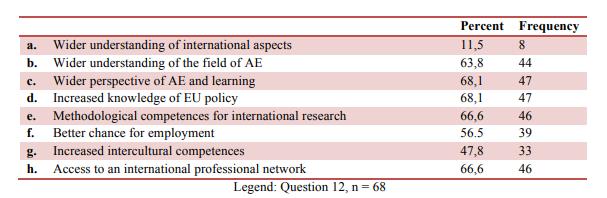

Looking at the valuation of the study program there is a difference to the motivation of the

students. “Wider understanding of international aspects” and “intercultural competences” are ranking

lower than the knowledge of adult education and European policy making. The motivation of the students

is not perfectly covered by the organization of the study program. Not a surprise: a better chance for

employment being in the organization of the study program is seen by little more than half of the students,

in this case, motivation and study program are fitting together (Fig. 5):

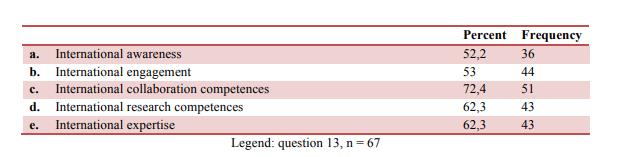

What did the students learn, so far? We asked for the competences they consider to be gained by

the studies. The result is in so far surprising, as “international collaboration competences” are agreed by 3

out of 4 students, with the highest frequency. This means that the elements of communication with

professors and other students from abroad, the direct interaction and the development of common projects

are of high value in the study program. “International awareness” is at the end, but still agreed by more

than half of the students.

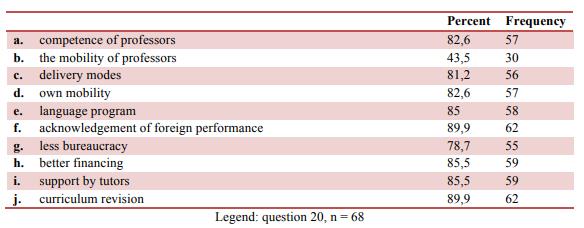

Somehow the students in the ESRALE study program are experts of the organization of

internationally oriented study programs. So, we asked what should be improved to run the study program

in a better way. The highest ranking of answers to this question has “acknowledgement of foreign

performances” (to make use out of it for the studies being enrolled in) and “curriculum revision”, to adapt

the curriculum more to the international outreach. On the second place is mentioned, “better financing”

(ERASMUS is positive, but for many students too little) and “support by tutors” (in the home university

as well as abroad). Much less important is the mobility of professors – in the eyes of the students.

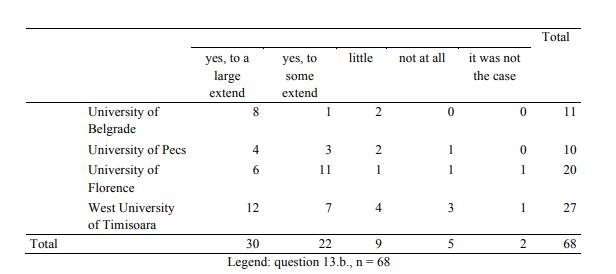

So, in general, the students are fond of the international aspects of the study program – most of

them are exposed to it since some semesters. Looking at the four universities the students are enrolled in

this general valuation does not have significant differences. In more detailed aspects of the study

programs, of course there are different views, even they are not always significant. This can be

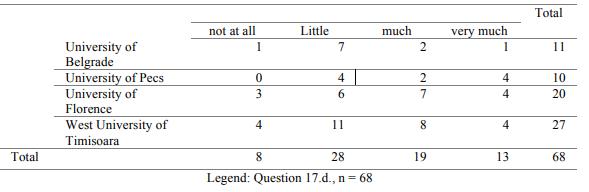

exemplified in the answers regarding the organization of the curriculum.

In general, the answers are balanced, the majority of the students acknowledge the international

efforts in the curriculum. Looking at the very positive, an even enthusiastic response was given to the

question, whether the motivation for international engagement is raised by the studies; four out of five

students consider their motivation to be developed. A bit hesitating here are only the students in Florence.

Not a big surprise are the opinions of the students about the relevance of the academic studies for the

practical work in adult education, since there is a critical view not only regarding the aspects of

internationalization. More than half of the answers consider the competencies (mainly international ones)

as improved for practical work by answering “little” or “not at all”. This opinion is related to the

motivation, where the labor market was low ranked compared with the personal development. Obviously,

international elements are not playing a big role in the work of adult educators in the national context, and

the international labor market mobility in adult education is not (yet) well developed.

There are no significant differences between the universities, showing that this situation is in common

at least amongst the participating four countries.

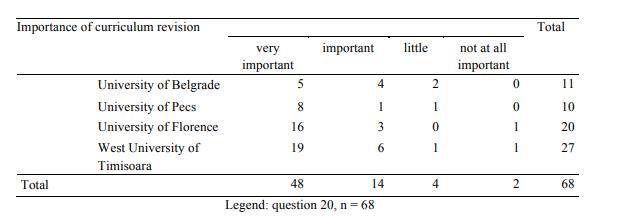

Regarding the curriculum revision, which has been the strongest wish of the students (s. Fig. 6),

there are the clearest differences between the universities. Mainly Florence is asked to develop further the

curriculum, also Timisoara, whereas Belgrade is valued closer to the demands of an international study

program.

4.Conclusions

The focus of our survey was the realization and valuation of international elements of study

programs in the eyes of students, following the hypothesis that there is a certain benefit for them. The

need to identify the student’s opinion, as the beneficiary of the study programs designed for them is

highlighted in different studies (Palomares, Pietkiewicz, 2015). In general, it can be said that the students

appreciate an international dimension of their studies as means of developing their personality, awareness

and understanding. But on the other hand, there is a lot of doubts and critics regarding the implementation

of internationality in the real context of studying. The comments are related mainly to the following

aspects:

=Curriculum: The curriculum is considered to be not perfectly adapted to the needs of

internationality and should be – in the eyes of the students – further developed. In this

development should be included also a better practical impact and a better tutoring inside the

“home university” and abroad. Such results are reported in most of the studies analyzing the

running of the international study programs (Hoare, 2013, Lodge, Bonsanquet, 2014, Sursock,

2014, Soria, Troisi, 2014), as the complementarity and the balance between international/

national/ local contexts, and culturally specific contexts are very difficult to ensure.

Mobility: The mobility of professors is not very important, the students want to be more mobile, but obstacles are the too little grant for travelling, formal problems of compatibility and recognition between different universities.

Labor market: The labor market does not play a big role for the students, neither in their motivation nor in their expectations for the future. In the national labor market is not seen a big impact on international aspects, and the mobility into a foreign country is not seen as very realistic. They do not necessarily attend the master for accessing an international labor market, but more for a wider understanding and perspective.

Personal development: A high importance has the personal development for the students, a wider horizon, a better understanding and knowledge. Obviously, this can be reached in the study programs being enrolled in.

Such findings are in line with the problems and challenges of internationalization underlined by the students European-wide. Still, after more than 10 years of implementing the Bologna process, the barriers of academic birocracy, of different country regulations, of inadequate support system in international offices and administration of the university etc. are fare from being solved (Palomares, Pietkiewicz, 2015, European Commision, 2015, UEFISCDI, 2013). The different cultural contexts in different universities are also challenges to be overcome, as they influence the teaching-learning situation, the relation student-teacher/ student-student (Sava, Danciu, 2015, European Union, 2014, Hoare, 2013). Also, the students even are not very optimistic about added value on the labor market, considering that the employers will not necessary appreciate higher an international master, they value such master offer mainly for their personal development, as they are concern with a better understanding of the global issues, as other studies are also underlining (Soria, Troisi, 2014, Lehtomäki, Moate, Posti-Ahokas, 2015, Foster, Yaoyuneyong, 2016), with implications on their level of competence and expertise at the future working place as well.

However, even the data presented in the explorative study have the limitation of the small number of respondents, it is consistent with the other researches carried out on bigger samples, and it gives the necessary hints for a more into depth further research and points of improvement of the study programs. Some of the improvements are on the hand of the academic staff to implement, but the more general and common ones, related to the formal, legal and financial aspects will last, unless higher levels of management and policy making do not adopt measures for a more functional internationalization of the study programs.

References

- Beelen, J., Elspeth J. (2015). Conceptualising internationalisation of the curriculum - Redefining Internationalisation at Home. In A. Curaj, L. Matei, R. Pricopie, J. Salmi, P. Scott (Editors, 2015) The European Higher Education Area Between Critical Reflections and Future Policies. Springer Open. DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-20877-0, p.59-76.

- Bernhardsson, N. & Lattke, S. (eds.) (2011). Core Competencies of Adult Learning Facilitators in

- Europe. Findings from a Transnational Delphi Survey. Retrieved from:

- www.dpu.dk/ASEM/events/RN3/QF2TEACH_Transnational_Report_final_1_.pdf

- CEDEFOP (2013). Trainers in continuing VET: emerging competence profile. Luxembourg: Publications

- Office of the European Union. Retrieved from:

- http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/EN/Files/4126_en.pdf

- Commission of the European Communities. (2013, EC). Thematic Working Group on Quality in Adult Learning. Final Report. Oct.2013. Retrieved from: http://ec.europa.eu/education/policy/strategicframework/doc/2013-quality-final_en.pdf de Wit H., Engel L. (2015). Building and deepening a Comprehensive Strategy to Internationalise Romanian Higher Education. In A. CUraj, L. Deca, E. Egron-Polak., J. Salmi (Eds.). Higher Education Reforms in Romania Between the Bologna Process and National Challenges. London: Springer, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-08054-3, p.191-204 European Commission (2015). The European Higher Education Area in 2015: Implementation Report Bologna Process. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. doi: 10.2797/128576.

- Retrieved from: http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/education/eurydice/documents/thematic_reports/182EN.pdf European Union (2014, EU). The Erasmus Impact Study. Effects of mobility on the skills and employability of students and the internationalisation of higher education institutions. Brussels: European Union. Retrieved from: http://ec.europa.eu/education/library/study/2014/erasmusimpact_en.pdf European University Association (2013, EUA). Internationalisation in European higher education: European policies, institutional strategies and EUA support. Brussels. Retrieved from: http://www.eua.be/Libraries/publications-homepage-list/EUA_International_Survey Foster, J. & Yaoyuneyong G. (2016). Teaching innovation: equipping students to overcome real-world challenges, Higher Education Pedagogies, 1:1, 42-56, DOI: 10.1080/23752696.2015.1134195 Gregersen-Hermans, J. (2015). The Impact of Exposure to Diversity in the International University Environment and the Development of Intercultural Competence in Students. In A. Curaj, L. Matei, R. Pricopie, J. Salmi, P. Scott (Editors, 2015) The European Higher Education Area Between Critical Reflections and Future Policies. Springer Open. DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-20877-0, p.73-94.

- Guri-Rosenblit S. (2015). Internationalization of Higher Education: Navigating between Contrasting Trends. In A. Curaj, L. Matei, R. Pricopie, J. Salmi, P. Scott (Editors, 2015) The European Higher Education Area Between Critical Reflections and Future Policies. Springer Open. DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-20877-0, p.13-26.

- Hoare, L. (2013). Swimming in the deep end: transnational teaching as culture learning?, Higher Research & Development, 32:4, 561-574, Retrieved from: Education DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2012.700918.

- Knight, J. (2013). The changing landscape of higher education internationalisation – for better or worse?

- Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 17:3, 84-90. Retrieved from: DOI: 10.1080/13603108.2012.753957 Lattke, S., Jutte, W. (2014, eds.). Professionalisation of Adult Educators – International and Comparative Perspectives. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Lehtomäki E., Moate J. & Posti-Ahokas H. (2015): Global connectedness in higher education: student voices on the value of cross-cultural learning dialogue, Studies in Higher Education, DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1007943 Lodge, J.M. & Bonsanquet A. (2014) Evaluating quality learning in higher education: re-examining the evidence, Quality in Higher Education, 20:1, 3-23, DOI: 10.1080/13538322.2013.849787 Milana, M., J.Holford (2014, eds.). Adult Education Policy and the European Union – Theoretical and Metholodogical Perspectives. Rotterdam: Sense /Publishers; https://www.sensepublishers.com/media/1971-adult-education-policy-and-the-european-union.pdf

- Nuissl E., Sava, S. (2010). Qualifying for European Adult Education. In S. Medić, R. Ebner, K. Popović (eds, 2010). AdultEducation: The Response to Global Crisis, Strengths and Chalenges of the Profession, Beograd: Ed. Čigoja štampa Nuissl, E., Lattke, S., (2008, eds.). Qualifying Adult Learning professionals in Europe. Bielefeld: W.

- Bertelsmann Verlag; Odağ O., Wallin H.R., Kedzior K. (2016). Definition of Intercultural Competence According to Undergraduate Students at an International University in Germany. Journal of Studies in International Education.vol. 20, 2: pp. 118-139..

- OECD (2016). The internationalisation of doctoral and master's studies. Education Indicators in Focus,

- No. 39, Paris: OECD Publishing. DOI:DOI: 10.1787/5jm2f77d5wkg-en. Retrieved

- from: =http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/the-internationalisation-of-doctoral-and-master-s-

- studies_5jm2f77d5wkg-en

- Palomares F.M.G., Pietkiewicz K. (2015, eds.). Bologna with Students Eyes 2015 – Time to meet the expectations from 1999. Brussels: The European Students’ Union. Retrieved from: http://www.esu-online.org/asset/News/6068/BWSE-2015-online.pdf Perry, L.B. & Southwell L. (2011) Developing intercultural understanding and skills: models and approaches, Intercultural Education, 22:6, 453-466, DOI: 10.1080/14675986.2011.644948 Research voor Beleid, (2010). Key competences for adult learning professionals. Contribution to the

- development of a reference framework of key competences for adult learning professionals. Final

- report, =Zoetermer, =Retrieved =from: =http://ec.europa.eu/education/more-

- information/doc/2010/keycomp.pdf;

- Research voor Beleid. (2008). ALPINE – Adult Learning Professionals in Europe. A study of the current situation, trends and issues. Zoetermeer. Retrieved from: http://ec.europa.eu/education/moreinformation/doc/adultprofreport_en.pdf Sava S., Danciu E. (2015). Students’ perception while enrolling in transnational study programs. In

- Procedia =- =Social =and =Behavioral =Sciences =180 =(2015) =448 =– =453. =DOI:

- 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.02.143. ===Retrieved ====from:

- http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042815014895

- Sawir, E. (2013) Internationalisation of higher education curriculum: the contribution of international

- students, =Globalisation, =Societies =and =Education, =11:3, =359-378, =DOI:

- 10.1080/14767724.2012.750477

- Slowey,M., Schuetze H.G. (2012). All change-no change? Higher education and lifelong learners revisited. In Slowey,M., Schuetze H.G. (eds.). Global Perspectives on Higher Education and Lifelong Learners. London: Routledge Soria, K. M., Troisi, J. (2014). Internationalization at Home Alternatives to Study Abroad: Implications for Students’ Development of Global, International, and Intercultural Competencies. Journalof Studies in International Education, 18: 261-280, doi:10.1177/1028315313496572 Sridharan, B., Leitch, S., & Watty, K. (2015). Evidencing learning outcomes: a multi-level, multi-dimensional course alignment model, Quality in Higher Education, 21:2, 171-188, DOI: 10.1080/13538322.2015.105pport1796 Sursock, A. (2015). Trends 2015: Learning and Teaching in European Universities. Brussels: European University Association (EUA). Retrieved from: http://www.eua.be/Libraries/publicationshomepage-list/EUA_Trends_2015_web.pdf?sfvrsn=18 Trede, F., Bowles W., Bridges, D. (2013). Developing intercultural competence and global citizenship through international experiences: academics’ perceptions. Intercultural Education. 24:5, 442-455, DOI: 10.1080/14675986.2013.825578Waterval, D.G.J., Frambach, J.M., Driessen E.W., Scherpbier A.J.J.A. (2015). Copy but Not Paste: A Literature Review of Crossborder Curriculum Partnerships. Journal of Studies in International Education, Vol. 19(1) 65–85. jsi.sagepub.com, DOI: 10.1177/1028315314533608 Williams J. (2016) A critical exploration of changing definitions of public good in relation to higher education, Studies in Higher Education, 41:4, 619-630, DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2014.942270

- Yamada, R. (2014). Comparative analysis of learning outcomes assessment policy contexts. In H. Coates (ed., 2014). Higher Education Learning Outcomes Assessment – International Perspectives. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Nuissl, E., Sava, S., Malita, L., Crasovan, M., & Danciu, L. (2017). International Studies: Added Value For Professionalization?. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 431-444). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.53