Abstract

The paper presents the main findings of a field research performed in different regions of Romania in the framework of the project

Keywords: CultureAdult Educationmulticultural groupsdialoguecollaboration

Introduction

The paper presents results from a field research performed in Romania to identify the training

needs of Adult Educators who work with multicultural groups, in the view of designing a training

curriculum for them to promote dialog and collaboration among multicultural learners. The research was

performed within the Erasmus+ project “Us&Them:dialog, tolerance, collaboration for good coexistence

The analysis we made showed that currently in Europe exist many ethnicities, each country

hosting national and immigrant ethnic/cultural minorities. According to Nation Master (2016), Austria

has 11.5% Croatians, Slovenes, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Roma, Turks, Bosnians, Serbians; Cyprus

has 18% Turks; Spain is a composite of Mediterranean and Nordic types; Ireland has 12.6% white,

Asian, black, mixed; Italy has clusters of German, French, Slovene, Albanian, Greek; Portugal is a

Mediterranean stock with citizens of black African descent & East Europeans; Romania has 10.5%

Hungarians, Roma, Ukrainians, Germans, Russians, Turks; Turkey has 20% Kurdish, Albanian, Bosnian,

Arabs, Tatars, Armenians, Greeks; United Kingdom has 16.4% Scottish, Welsh, Irish, black, Indian,

Pakistani, mixed. The European Union Census (2011) in these countries reported various religions:

Muslims, Roman Catholics, Protestants, Hebrew, Hindu, Presbyterian, Anglican, Methodist, Reformed,

Pentecostal, Orthodox, Sunni, Alevi or Sufi.

The social tensions and the anti-social deeds generated by multiple factors (such as different

religious background, different cultural traditions, affiliation to different ethnicities or social clusters, etc.)

can be defused and prevented through non-formal and informal education and training for tolerance,

acceptance, opening, understanding and reciprocal knowledge, which is exactly what the “Us&Them”

project tries to do, by aiming to train the adult educators to promote tolerance and the understanding of

“the other” in multilateral communities. The target groups are (a) AE educators; (b) adult learners from

cultural conglomerates.

Theoretical Foundation and Related Literature

Kymlicka (2012) analyses the myths about multiculturalism and brings viable arguments in favour

of the thesis that “Talk about the retreat from multiculturalism has obscured the fact that a form of

multicultural integration remains a live option for Western democracies” (p.5). Among the factors that

can either facilitate or impede the successful implementation of multiculturalism, he points on

desecuritization of ethnic relations, by stating that

state and minorities are seen as an issue of social policy, not as an issue of state security” (p. 6); it also

emphasizes that “Multiculturalism is first and foremost about developing new models of democratic

citizenship, grounded in human-rights ideals” (p. 12).

HarperCollins Dictionary (1991) states that multiculturalism protects cultural diversity, and

defines it as the acknowledgement and promotion of pluralism as a feature of many societies. In

multicultural societies, educators should incorporate in educational practices the adult learners’ culture

and “[…] educational strategies must be developed to minimize the potential for further exclusion and

Quite a controversial issue for nowadays Europe, multiculturalism has been analysed within the

context of EU shared democratic values, from various culture-related angles and perspectives. In October

2010, the German Chancellor Angela Merkel declared

2011, in an immigration-crime-employment related discussion, the French President Nicholas Sarkozy

stated on TF1 that multiculturalism

multiculturalism is not easy to be handled and that Europe needs to search for more viable solutions in its

efforts to achieve real common European cultural identity.

In spite of studies emphasizing the fact that not the ethnic or religious identity are indicators of

tensions within multicultural groups but rather some other socioeconomic factors like, for example,

unemployment and poverty (Van Driel, Darmody & Kerzil, 2016), Sharpes & Schou (2014) stressed that

ethnicity and cultural values does matter, especially in educational contexts in which educators have to

observe the traditional democratic values on one hand, and in the same time to support and facilitate the

integration of minorities into communities and schools.

In the multicultural Europe, social norms of tolerance should be commonly shared. In 2015, the

European Association for the Education of Adults (EAEA) officer Tania Berman, in charge with the

EAEA project called "Awareness Raising for Adult Learning and Education" (ARALE), emphasized that

“Education is much needed” and “[…] learning can be a solution to religious and cultural hatred”.

Adult Education can highly contribute with solutions to the multifaceted problems of nowadays

multicultural societies. Educators within different cultural groups have an important role to play,

especially in light of the refugee crisis. EAEA believes that Adult Education is one of the most effective

tools to foster tolerance and counter stereotypes, and it should not only be looked at through the lens of

growth and jobs (Halachev, 2015).

Methodology

The research has investigated the state-of-the-art regarding (1) the main features of existing

cultures in Romania (principles, practices, ideas, values, patterns in human behaviour, thought and

feelings, human activities, social standards) and (2) the misunderstandings, prejudices, stereotypes as

potential sources of socio-cultural tensions. The final aim was to use the research findings to design a

customized curriculum for adult educators of inter- and multicultural and groups.

We based our research on the following questions:

cultures? If so, which are the sources? What could be potential solutions? Which are the training needs

of adult educators in the field of intercultural education?

Our field research was achieved through questionnaire and Focus Group and was implemented

between 10.12.2015 – 11.02.2016. The survey envisaged different regions of Romania (the Counties:

Argeş – Southern part of Romania, Constanţa – South-Eastern part, Bistriţa-Năsăud – Central-Northern

part and the capital Bucharest), with the purpose of having a holistic image on the existing cultures,

ethnicities and religions, on people’s perceptions about them and on typical or specific relations and

behaviours of representatives from majority population and national minorities.

The questionnaire was delivered to 60 respondents, via email. We got 57 filled in questionnaires,

of which 50 were complete and we kept them for analysis (36 from women, 14 from men). Respondents’

average age: 40.57 years. The target audience was selected by snow balling with provision for maximum

differentiation in terms of: a) ethnicity/religion/culture; b) geographic distribution; c) educational strand

(academic, technical, other).

The Focus Group was achieved with 4 participants (3 males, 1 female). The respondents were

adult educators, researchers, theologians, priests (each having one or two professional positions), more

than half holding master and PhD diploma. Prior to the Focus Group, all participants have signed an

Informed Consent. The duration was of two hours and a half. The Focus Group has been video recorded.

Results

Results from Questionnaires

92% of the respondents are aware of people from other cultures living in their area. The

culture/religion/ethnicity/civilization that the respondents identified as living in their area were: Roma

(98%), Christians (58%), Eastern Europeans (46%), Jews and Turks (36% each), Chinese and

Catholics (28% each), Russians (26%), Latin (24%), Filipino, Vietnamese & Latin-Americans (20%

each) and other in less than 20% (i.e. Africans, Maghrebi, Indian, Buddhist, Armenians, Maronites,

Bangladeshi, Pakistani and Sri Lanka).

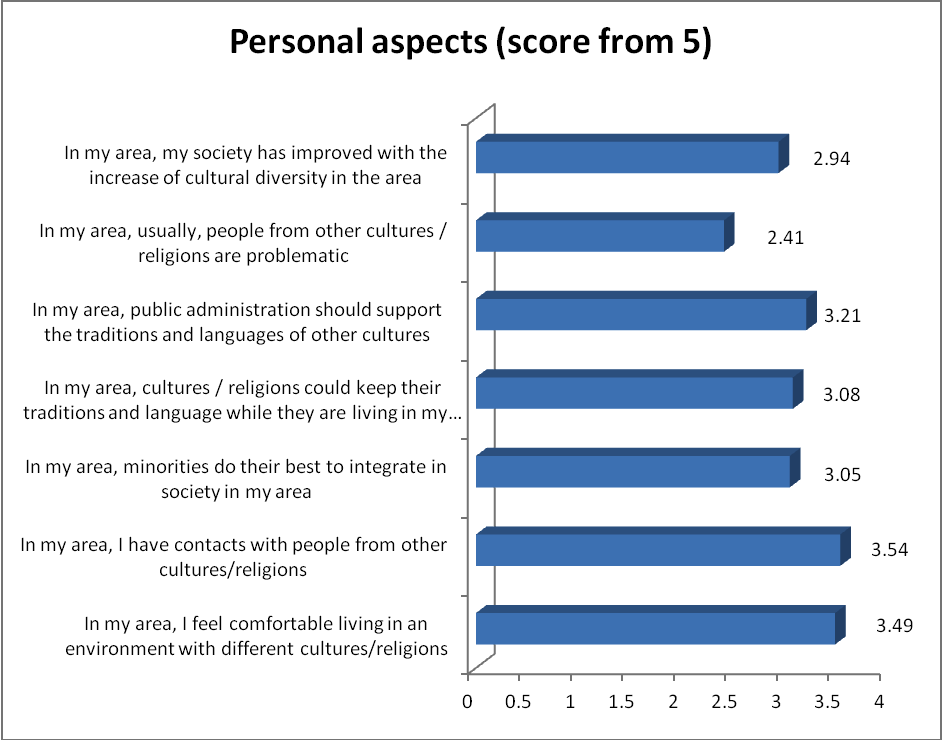

Although the scores obtained regarding their interaction with other cultures and religions existing

in the area where they live are not the highest score possible, as shown in figure

comfortable with living in multicultural societies (3.49) and interacting with “the others” (3.54). Probably

an aspect requiring more attention and remedies from authorities refers to supporting more the traditions

and languages of other cultures, as the score this issue got is relatively high (3.21).

Regarding the role of media in relation to the existing cultures in the area of the respondents, the

answers show that media and media operators perform not so satisfactorily, as the obtained scores are

only slightly above the average (1 = the least satisfying, 5 = the most satisfying) namely:

give a right image of different cultures living in my area” scored 2.52, “News about other cultures are

mainly related with negative aspects: violence, extremism, etc.” scored 2.64, “Media informs under equal

conditions about any culture in terms of activities, traditions, etc.” scored 2.73.

The questionnaires provided extremely large scale of culture features and due to the diversity of

the presented cultures/religions/ethnicities is not possible to present them in summarised format here. But

we noticed that the major religions and ethnicities nominated by respondents are the same and have same

common features as the ones identified during the Focus Group. All the characteristics collected through

questionnaire can be the object of a further research.

To the question

vision, emphasizing that they are different concepts and correctly explaining what each notion mean to

them.

The answers to the question “Do you participate in any kind of initiatives/movements for the

result is balanced in a way, by the desire, opening and availability of the respondents to get involved in

near future to such activities.

The respondents declared that they do have contact with people from other cultures / religions

Unfortunately we could not identify a dominant response to the question

stereotypes linked to different cultures are true?” as the answers where homogenously spread (“Many

times are true”, “If it is said so, then there would be a reason for that”, “No, usually they are not true”,

“They are very rarely true”).

Results from Focus Group

The Focus Group revealed that in Piteşti, Argeş County and the Muntenia region there are

currently living several ethnicities and religions: Christians, Neo-protestants (including Adventists),

Catholics, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Roma, Greeks, Armenians, Bulgarians, Jews/Hebrew, Chinese,

Vietnamese and Indians. The participants could not estimate their exact size, in percentages, in the whole

population, but the cultures/ethnicities we enumerated before are listed from the largest size to the

smallest one. One participant (the priest) pointed out that he prefers to use ‘denominations’ instead of

ethnicities.

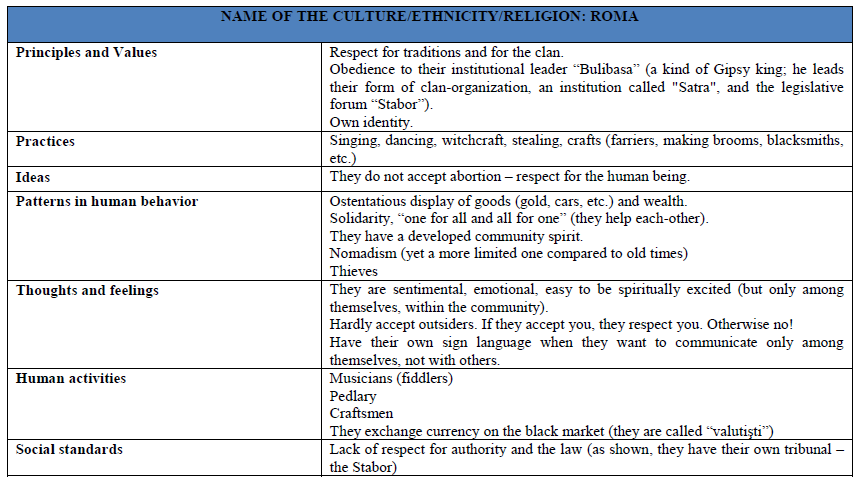

Because the time during the Focus Group did not allow us approaching all ethnicities/religions, the

participants selected and discussed only three of them. In tabel 2 below we included the description of the

Roma population, but more information on the features of the other cultures/religions/ethnicities living in

Romania can be obtained (by emailing to georgeta.chirlesan@upit.ro) from

specific features of diverse European cultures and sub-cultures” elaborated by the “Us&Them” project

coordinator.

The participants in the Focus Group pointed out that there is potential for conflict only with the

Roma population. The conflict sources refer to:

(a) the failure in complying with social norms and law (organizing noisy and long lasting

parties, trying to amaze the other by displaying wealth and assets, circumventing the law);

(b) social statute of discriminated minority (this is how Roma perceive themselves);

(c) low economic and educational level.

For the other two analysed minorities (Neo-protestant and Catholic) one cannot speak of conflicts

and sources of conflict, it is not the case, because they are not conflicting with the majority population nor

between each-other.

The opinions on the best ways to solve possible conflicts between

cultures/religions/ethnicities/civilizations unfolded from educational to economical spectrum, showing

that people think of a combination of ways to handle the situation and face problems, seeing that only a

joint effort can be the solution for cultural tensions. Pessimistic existed among respondents as well:

not think this kind of conflicts have a solution, because there will always be extremists in every culture /

religion / ethnicity / civilization, as history has shown us so far”. Some relevant positions given by

participants on conflict solutions are presented below:

-Giving up in having prejudices, showing mutual respect and implementing programs / projects promoting multiculturalism and multiethnic and multi-religious tolerance.

-Integration of a minority in the social life of a community requires, in some cases, efforts from both sides. But as long as the opening occurs unilaterally, positive results won’t appear.

-Obligation of minorities to justify their income to observe the financial obligations, to look for a job, to justify property.

- Communication in all its forms: verbal, non-verbal, informal, para-verbal, etc.

- Through getting support from the state, greater accountability standardized through fines and

regulations that to be applied to them equally, by determining them to provide a quiet space and

to fit in everything that involves the state and the environment where they live (refering to

Roma).

The Focus Group discussions concluded that the need for Adult Education training in intercultural

issues is quite big and will increase in the future due to migration trend and globalization (which increase

the mobility and free movement of persons). A suggestion was that the Adult Educators should be from

the minority communities (some ethnicities, like Roma, accept more easily to be educated and interact

during education and training sessions with their own representatives). Topics have been recommended

for intercultural education: intercultural communication; knowing the communities (getting knowledge on

the minorities); elements of history, culture and civilization of minorities; elements of acculturation;

cultural awareness techniques; soft-skills; entrepreneurial knowledge and skills for social and economic

initiatives (to be able to transfer them to the learners).

Discussions

The findings of our research reveal key-aspects regarding the existing ethnicities and religions in

Romania and the perception of the majority population on them. The largest ethnicity is the Roma one

(98%) followed by Easter Europeans (28%), while for the religions, the order is Christian (58%), Jewish

(36%) and Catholic (28%). Although highly compatible with the official data on ethnicities and religions

in Romania, we noticed a dissonance in the obtained results regarding Jewish and Catholic religions, as

Catholic not Jewish was found in latest census to be the second largest religion in our country after

Orthodox. This deviation could be explained by the fact that, when answering the questionnaire, our

respondents have relied only on personal perception and not on statistical information.

Media role is seen as important, by there is room for improvement of its actions when it is about

reflecting in a correct way the culture of co-existing minorities.

Our study sustained that Adult Education is important in multicultural communities due to its

potential in bringing positive changes at social level. This is convergent with statements of Carlson, Rabo

& Gök (2007) who shows that “It is hoped that education can be an agent for causing social and cultural

reforms and values to take root.”

Within the integration process of immigrants, besides housing and employment, education and

social & cultural adaptation to the new society are crucial factors. For these to be achieved, a joint effort

is required from immigrants, majority population and state with its institutions. As revealed by our

findings, in Adult Education within multicultural groups the focus should be on respecting and correctly

approaching and culture, ethnicity and religion. This is also supported by Brodnicki & Maliszewski

(2013) who show that “multicultural education should take into consideration and respect ethnic, racial

and cultural differences […]. Therefore it is a process of a dialogue of cultures, on the one hand

protecting from standardization and cultural homogenization, on the other – from local egocentrism.”

Conclusions

In Romania, there are three major ethnicities and religions that live peacefully together with the majority population (Orthodox): Roma, Neo-protestant and Catholic. All of them have well defined identity and present distinct features. The majority population has a good knowledge on each of them and has accepted them long ago. The co-existence among them and majority is a good one, there are no conflicts (except the conceptual ones). In the case of Roma-Romanian relationship, tension exists due to Roma’s lack of respect for law, authority and work. The other two cultures - Neo-protestant and Catholic – are not conflictual with the majority population (Orthodox). On the other hand, the Roma people see themselves as being discriminated and are perceived as such by many from the majority population.

Discrimination is only one potential source of conflicts with Roma, besides low education and economic level and a series of habits, traditions and customs they have (their music, their way of life, etc. which sometimes disturb the public order).

In spite of the existing differences, we may appreciate that the area is a peaceful one, with a high level of security, with low risk of future conflicts between the co-existing cultures. The spiritual values of each culture together with their practices represent valuable assets that give uniqueness and shape the local colour of life and society here.

Acknowledgements

This work has been carried out within the project

References

- Brodnicki, M., Maliszewski, T. (2013). Adult Education in Multicultural Communities. The Case of the City of Gdansk History. Lifelong Learning. Continuous Education for Sustainable Development. Saint-Petersburg, 1(11), 223-227

- Carlson, M., Rabo, A. & Gök F. (2007). Education in ‘Multicultural’ Societies. Turkish and Swedish Perspectives. Swedish Research Institute in Instanbul, Transactions (Vol. 18, p. 248) 2011 European Union census. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2011_European_Union_census

- Halachev, R. (2015). What role does adult education play in the refugee crisis? Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/epale/en/blog/what-role-does-adult-education-play-refugee-crisis

- Jary, D., Jary, J. (1991). HarperCollins Dictionary of Sociology. New York: HarperPerennial

- Kaya, H. E., (2014). The Road Ahead: Multicultural Adult Education. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, Vol. 4, 8(1), 164-1668

- Kymlicka, W. (2012). Multiculturalism: Success, Failure, and the Future. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Transatlantic Council on Migration

- Nation Master. (2016). Countries Compared. Retrieved from http://www.nationmaster.com/country-info/stats/People/Ethnic-groups

- Sharpes, D. K., Schou, L. R. (2014). Teacher Attitudes toward Muslim Student Integration into Civil Society: a report from six European countries. Policy Futures in Education, 12 (1), 48-55.

- Van Driel, B., Darmody, M., Kerzil, J. (2016). Education policies and practices to foster tolerance, respect for diversity and civic responsibility in children and young people in the EU. NESET II report, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, doi:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Chirleşan, G., & Chirleşan, D. (2017). Working with Multicultural Groups: a Culture and Ethnicity Case Study in Romania. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1984-1991). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.245