Abstract

Career counseling has emerged as a way to respond to social pressures imposed on the implications of this phenomenon in the ever-changing relationship between jobs supply and demand, raising the quality of requested skills as well as efficiency, in a client commitment manner. Career counseling theoretic literature abounds in models and strategies that when put into practice simply do not work, not because they are wrong, but because client’s expectations and beliefs are so different. The main focus of this paper is to analyze youth perception on career counseling activities, for a better understanding of what triggers them to be fully active into the process. The purpose of current paper is to identify the relationship between perceived employment barriers and perceived employment support of 432 last year students and young graduates from 4 European countries. The curvilinear relationship identified, shows that very high and low scores on perceived employment barriers significantly influences the outcome of the career counseling process, while medium scores on perceived employment barriers, gives youth incentives for authentic receiving of career counseling services, mostly in terms of employment support. Conclusions and practical implications are discussed.

Keywords: Youth employabilitydynamic relationshipperceived employment barriersperceived employment support

Introduction

Career theory provides a conceptual framework for the career choice process from its initial

changes to the developmental adjustments that individuals make throughout life. Patton and McMahon

(2006) have analyzed most recent developments in career theory and counseling, emphasizing about the

shift from a static to a more dynamic approach, thus constructivists approaches in career counseling

theory representing one of the most significant challenges to career counselors trained in positivists

approaches. Authors detail the move toward convergence in career theory, and the subsequent

development of the Systems Theory Framework (STF), thus connecting theoretical and practical

approaches of career counseling.

In modern philosophy, the moral of "The Fox and the grapes" fable is associated with the so-called

cognitive dissonance, specifically with the feeling we face when dealing with a conflict between more

things that we care about. In the fable, the contradiction arises between the fox’s self pride and the

unwillingness to be deceived, saying that the grapes are too green and too sour, as long as it could not

reach them.“Sour grapes” is a beautiful example of behavior-induced attitude change, also working in the

opposite direction, meaning improving attitudes towards things we feel we can have.

Thus, the sour grapes effect refers to the tendency to justify a decision, in our case a career related

choice, by overlooking any faults seen and overrating positive aspects. In a career counseling process,

young clients are more likely to give a positive feedback to a newly accepted job position than a negative

one, due to acknowledging past choices as rational and well-made. Employers could embrace this bias,

reinforcing young employee’s correct choice post-hiring. This built-in mechanism aims to make clients

feel better about any poor decisions they made related to committing to a job, especially the case when

settling down to a specific profession. Given young clients emotional investment when choosing a

specific professional path and later on job, their pre-existing “brand” loyalty, many clients will refuse to

admit, in spite of any shortcomings experienced with the career decision made (few job openings, low

income, lack on internship), that their decision was made in poor judgment.

Career counseling strategies have become more aware of the differing needs of clients, focusing on

individual strengths, empowering change, contributing to clients’ personal development and providing

individual action planning towards idealized work or other educational settings.

This idea resides in Robert Cialdini’s Principle of Commitment (1984). The concept highlights

human’s deep-rooted psychological desire to stay true to what they have committed to, because it is

directly related to self-image, therefore attempts to rationalize any poor career decision justifies the choice

made and protects the self-image. Related to this, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) (Hayes,

Strosahl, & Wilson, 2003), has demonstrated efficacy and effectiveness with a diverse range of clients

along with their problems, such as depression, anxiety, stress, and negative affectivity (Hayes, Luoma,

Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006). ACT main objective is to enhance client’s psychological flexibility by

increasing acceptance of internal experiences, confronting experiential avoidance, contextualizing

problematic cognitions, exploring personal values and associated goals, and fostering commitment to

moving forward in the direction of one’s chosen life values (Hayes, 2002).

A client’s anxiety about career indecision, as theory authors Hoare, McIlveen, and Hamilton

(2012) deliniated, relates to their past learning experiences and negativ self and others discourse, when

recalled in the present under situations of stress or uncertainty, dramatically undermine beliefs in the

capacity to make a decision.

Methodology

This paper deals with applying the theoretical principles of STF and ACT to the activities

undertaken during career counseling services, with the purpose of testing the dynamical relationship

hypothesis between perceived employment barriers and perceived employment support, currently under

research focus in the field of dynamic career counseling.

This study has been performed under an Erasmus project mainly focused on the needs of the

unemployed youth from the participant countries: Romania, Turkey, Hungary and Cyprus, aiming to

improve the quality and accessibility of educational and training provisions by enhancing youth

employability skills. During the project, there was elaborated a questionnaire focused on identifying

youth vocational counseling needs and their perceptions related to the usefulness of current career

counseling services that they have participated to.

Current study is focused on identifying the relationship between perceived employment barriers

and perceived employment support of 432 last year students from Romania, Turkey, Hungary and

Cyprus.

Among other questions that are not the subject of this current research, young people were asked

to rate (1=lowest, 5=highest) 6 issues that they consider bringing them support in finding a job (Item 15).

Aspects regarded referred to: understanding the work flow, a person assigned to show them around and

introduce them to the team, on the job training, mentoring/coaching, team building activities, and

induction.

Regarding perceived barriers, young people were asked to rate (1=lowest, 5=highest) 7 issues that

they consider to be barriers when going from unemployed to employed (Item 13). Aspects referred to:

commuting, necessity to work from early ages, lack of key skills, lack of experience, lack of professional

opportunities in the field, lack of opportunities in their country, poor language skills, personal health

issues, lack of industry, lack of information, limited access to internet/personal computer, lack of personal

development/self-awareness, the need to get a job, receiving financial support from their families, being

under-aged.

Regarding our target group, a total of 432 youth have voluntarily responded to our online

questionnaire. Out of the total number of respondents, 38,2% are masculine and 61,8% are feminine

youth respondents, 46,1% are aged between 15 and 19 (last year high school teens), 20,4% are aged

between 20 and 24, (last year students) and 33,6% are aged between 25 and 29, (master students).

Results

Current research takes the position that perceived employment barriers and support relationship is

a dynamic one, these considerations leading to Hypothesis: Perceived employment barriers and perceived

employment support are in a dynamic relationship.

In curvilinear relationships variables grow together until they reach a certain point (positive

relationship) and then one of them increases while the other decreases (negative relationship) or vice

versa (Balas Timar, Aslan, 2016).

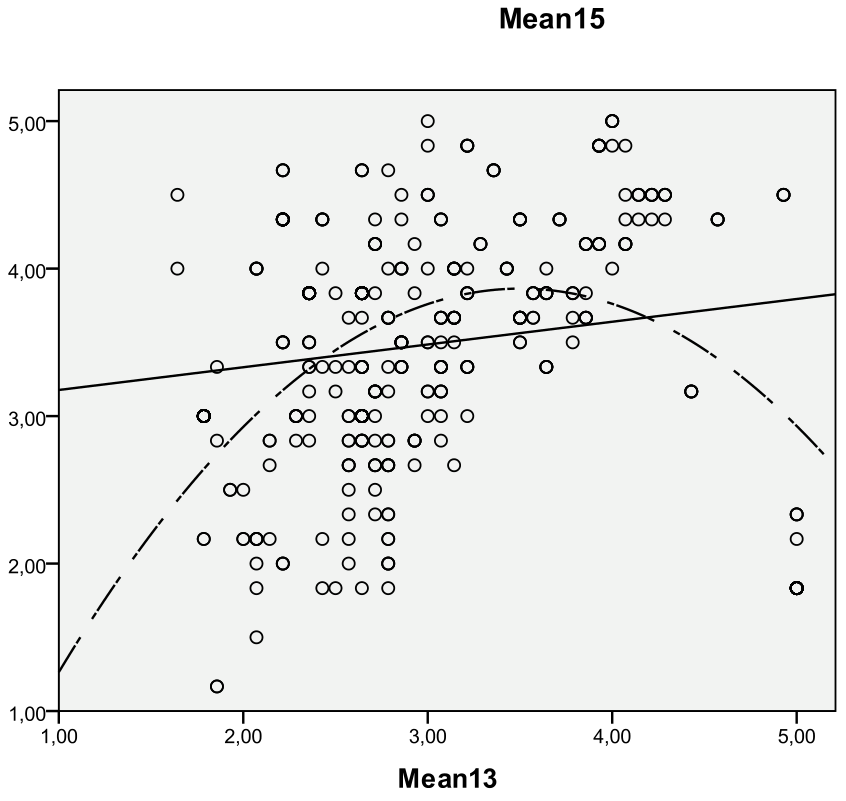

The Scatterplot diagram presented in Figure

perceived employment barriers on the horizontal axis and perceived employment support, represented on

the vertical axis. The sample consists of 432 last year students and young graduates from: Romania,

Cyprus, Hungary and Turkey.

We have used a confirmatory factor analysis, based on multiple regression analysis for curvilinear

effects, in order to test our hypothesis that states that between perceived employment barriers and

perceived employment support there is a significant dynamic relationship.

Results show a very high correlation between perceived employment barriers – Item 13

(MD=3,486, D=0,810) and perceived employment support – Item 15 (MD=3,004, SD=0,815) of r = 0,155

significant at a p < 0,01 methodologically allowing us to further proceed with confirmatory factor

analysis.

We have used the hierarchical multiple regressions, the dependent variable being perceived

employment support, and the dependent variable in step 1 perceived employment barriers, and in step 2

squared perceived employment barriers.

The fitting of the two models is presented in Table

Model 2. As it is shown in Model 1 the model that supposes linear relationship, perceived employment

barriers accounts for 2% of the variance in perceived employment support with an F = 10,596 significant

at a p < 0,01. In Model 2, the model that supposes curvilinear relationship, perceived employment

barriers accounts for 18% of the variance in perceived employment support with an F = 51,160 significant

at a p < 0,01.

a. Dependent Variable: Perceived employment support (Item 15)

All standardized coefficients of Beta (B= 0,155; B= 2,927 and B= -2,792) are significant at p

values < 0,01 which gives a high consistency to our both models. The Beta coefficient’s changing sign

from + to – depicts the fact that the effect is growing in the opposite direction, demonstrating the

curvilinear relationship between perceived employment support and perceived employment barriers. The

additional incremental predictive capacity of 16 percents, added by including the squared perceived

employment barriers variable which curves the regression line, clearly prove that there is a dynamic

relationship between perceived employment support and perceived employment barriers.

This dynamic relationship demonstrates that extreme aspects (very low and very high) of

perceived employment barriers significantly influences perceived employment support, while situating on

the middle response zone, gives young graduates incentives for authentic receiving employment support,

mostly in terms of career counseling services.

As for now, there has not been reported any research proving the curvilinear relationship between

perceived employment barriers and perceived employment support, thus, these results may help

expanding the current body of knowledge on young graduates’ utility perception on career counseling

provided services in order to authentically lower youth unemployment rate.

4.Conclusions and Implications

This research brings methodological justification on how and to whom to implement career

counseling services, in order to fully obtain their purpose. When working with youth that have very low

or high perceived employment barriers, it is better to firstly address their unbalanced work beliefs and

then to provide career support.

Nowadays offering career counseling services seems like a panacea in lowering youth

unemployment rates, but unfortunately very few participants perceive these services as professionally

useful, not because strategy is not efficient, but because youth unbalanced view over getting a job does

not allow them to fully participate in the process.

Current results suggest that offering career counseling services in an nondiscriminatory manner,

regardless youth beliefs about engaging in a working life, will not be perceived as a help coming from

professionals, but will be perceived as a mandatory activity to be enrolled in, only to self fulfill own

prophecies about employment: “There are too many barriers, I will never get a job, regardless how many

counseling services I will be provided with”, or the other way, „There are no barriers in finding a job, so

why should I look for career counseling services, they are useless since I know my own way.”

Theoretical explanation of this statistical conclusion can be approached by the Systems Theory

Framework (STF) of career development (McMahon, 2015), that has proven by far its translation into

practice, especially into career counselling and qualitative career assessment.

References

- Balas Timar, D. & Aslan, M. (2016). The dynamic relationship between perceived employment self-confidence and perceived employment challenges - a positive youth development approach to youth career counselling, Journal Plus Education, Special Issue, 2016.

- Cialdini, R. (1984). Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, New York: Quill.

- Hayes, S. C. (2002). Acceptance, mindfulness, and science. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 9, pp. 101-106.

- Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J., Bond, F., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Model, processes, and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, pp. 1-25.

- Hayes, S.C., Strosahl, K.D. and Wilson, K.G. (2003). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change. The Guilford Press. ISBN 1-57230-955-5.

- Hoare, N. McIlveen, P., Hamilton, N. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) as a career counselling strategy. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance. Volume 12, Issue 3, pp. 171-187.

- Lonka, K. & Ketonen, E. (2012). How to make a lecture course an engaging learning experience? Studies for the Learning Society, 2-3, 63-74.

- McMahon, M. (2015). The Systems Theory Framework of career development: Applications to career counselling and career assessment. Australian Journal of Career Development, Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 148-156.

- Patton, W. & McMahon, M. (2006). Constructivism: what does it mean for career counselling? (Ed. M. McMahon & W. Patton). Career counseling. Constructivist approaches. Oxon: Routledge.

- Patton, W. & McMahon, M. (2006). The Systems Theory Framework of Career Development and Counseling: Connecting Theory and Practice. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, Volume 28, Issue 2, pp. 153-166

- Ruismäki, H. & Tereska, T. (2006). Early childhood musical experiences: contributing to pre-service elementary teachers’ self-concept in music and success in music education (duringstudent age). European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 14(1), 113-130.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Timar, D. B., & Aslan, M. (2017). The Sour Grapes Effect in Youth Career Counselling. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1877-1882). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.230