Abstract

The education that traditionally was seen as beginning in childhood and ending in the period of transition to the adult life, acquires, nowadays, new meanings, the lifetime alternating periods of study and work. In this context and taking into account that every man spends more than a quarter of life at work, the workplace is looming to be crucial in making lifelong learning a reality by stimulating the motivation to learn and by the adults participation in education and training. The purpose of this paper is to investigate a vital issue for the contemporary society, where the requirements are getting higher: the issue of the adult education in general and mentoring, more in particular. To achieve this purpose, it was conducted a literature review to identify how mentoring is interpreted and applied in organizations. In this regard, the paper starts with a presentation of the crucial role that companies, through the types of training offered, meet at generating lifelong learning for their employees, continuing with the conceptual definition of mentoring as a mechanism for the transfer of knowledge and the development of skills within organizations. The analysis undertaken have identified a number of advantages and limitations regarding the mentoring process at the workplace, the final conclusion being that mentoring is a win-win process in which both parties can gain valuable benefits.

Keywords: Lifelong educationWorkplace learningMentoringSkillsKnowledge

Introduction

Adult learning in the workplace is a basic element for learning throughout life, especially if we

consider that most people spend a large part of their time at work, this becoming possible by stimulating

the motivation to learn and through adult participation in education and training. There is a range of ways that can lead to achieving adult education in the workplace, the employees being able to learn through the

work tasks assigned, from colleagues and mentors, by solving challenges that may arise, by job rotation,

and through continuous training that employers can offer, through various specialized courses.

Following the adoption of ambitious strategies and introducing a number of new models of work

organization, companies are becoming more aware of the lack of certain skills, rending imminent the

need for continuous training. In this regard, the employer has the responsibility to create all the conditions

in the workplace for employees to continue learning and to develop their skills.

A key indicator for the crucial role that work has in lifelong learning may be the proportion of

companies that offer training. According to Eurostat, in 2010, at EU level, 66% of companies provided

continuous training to their employees, percentage with 6 points higher as compared to 2005. Among the

analysed countries, most of them recorded an increase of this percentage, in 2010 compared to 2005,

exception made by Poland (13% decrease), Romania (16% decrease), Great Britain (10% decrease). The

largest increase was recorded in Belgium, where the percentage of firms that provide continuous training

to their employees was, in 2010, 78% versus 63% in 2005.

Source: Eurostat. Vocational education and training statistics. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-

explained/index.php/Vocational_education_and_training_statistics#Further_Eurostat_information, consulted on 17.08.2016.

In 2010, at EU level, 56% of companies were offering to their employees training as a form of

continuous learning, while 53% were conducting other types of continuous education (such as training

on-the-job, job rotation, study visits, workshops, self-directed learning). The proportion of companies that

offer courses as a form of continuous training of their employees exceeded 75% in Denmark and Sweden

(76%), situating above the EU average in several countries, including Belgium, Austria, Spain, France

and the Netherlands. In contrast, with less than 25% of the companies providing courses is positioned

Bulgaria (21%), Greece (21%), Poland (20%) and Romania (14%). The percentage of companies that

provide other types of training is noticeably higher, having in the top Denmark (84%), Austria (77%), UK

(75%), Sweden (74%).

Source: Eurostat Database. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/education-and-training/data/database, consulted

on 15.05.2016.

By comparing these results, we can conclude that there are countries where companies have a

higher probability of providing training to their employees, as well as some in which companies are more

likely to provide other types of training to their employees.

According to Allen & Eby (2007), in the context of changes occurring on the labour market and of

demanding working environments, maintaining updated knowledge and skills becomes essential. In this

context, lifelong learning is not only the obligation of a low-skilled, vulnerable on the labour market, but

a necessity and a responsibility for all, both employees and employers. (European Centre for the

Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop), 2011, p. 19)

As defined by the Council of the European Union (2011, p. 3), adult learning refers to all types of

learning, formal, non-formal and informal, general or vocational, made by adults after they finished their

initial education and training.

Learning in the workplace is seen by the European Centre for the Development of Vocational

Training (2011, p. 98) as including informal learning, non-formal, ad- hoc, practical and occasional

learning, incorporated into workplace, into work-related processes and tasks, for introducing new staff

members in the working processes of the company as well as for continuous development of experienced

employees. Both formal and informal learning are equally important elements of workplace learning,

involving, however, different processes and results. Thus, while informal learning occurs as part of daily

workflow processes, producing particularly implicit or tacit knowledge, formal learning takes place in the

context of organized training and learning activities, with the purpose of generating explicit, formal

knowledge and skills. Given these considerations, it is advisable that the different ways of learning in the

workplace to be combined so that the formal learning use informal learning. (Tynjälä, 2008, p. 140)

In conclusion, learning-at-work proves to be an effective form of training, as it allows immediate

application in the workplace of acquired knowledge and skills.

The Mentoring, a Successful Way to Transfer Knowledge and to Develop Skills

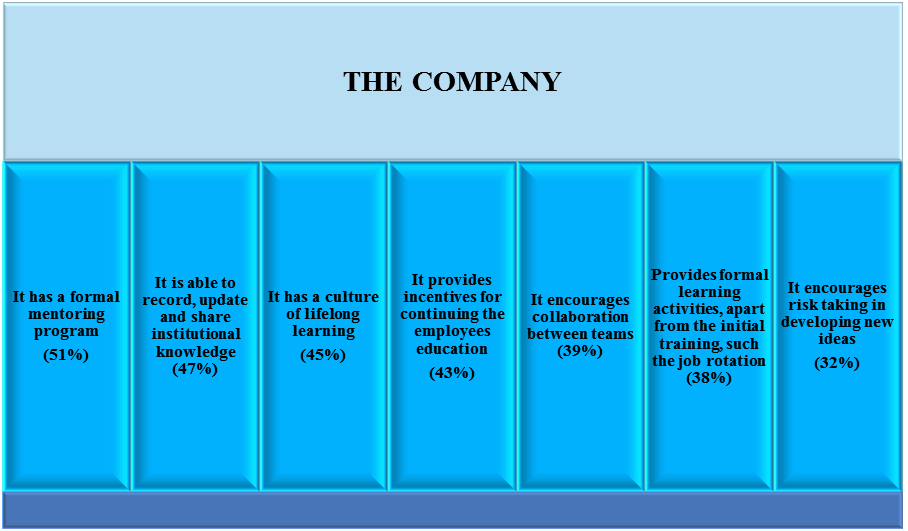

In order to establish an effective development strategy to ensure business performance, it is

imperative that companies anticipate the needs of future professionals. A study by Oxford Economics

shows that, in order to develop their skills, employees rely more on training and mentoring, 50% of

respondents expecting to receive more feedback from their supervisors than from colleagues from

previous generations. (Leloup, 2014, para. 1)

Source: Oxford Economics. Workforce 2020. The Learning Mandate. Retrieved from

http://www.oxfordeconomics.com/workforce2020/reports, consulted on 20.08.2016.

According to Cuerrier (2003), the mentoring can be defined as a form of voluntary help,

encouraging development and learning, based on an interpersonal relationship of support and sharing

where an experienced person (mentor) invests his accumulated wisdom and expertise in order to foster

the development of another person who has skills to acquire and professional goals to attain.

The protégé is a person looking for personal and professional fulfilment, motivated to use

knowledge, skills and values provided by a senior so as to facilitate the achievement of personal and

professional objectives. (ADASUM, 2015, p. 2)

As people go through different stages in life, they can experience several forms of mentorship, as a

way of learning specific to each stage: youth mentoring, academic mentoring, mentoring in the

workplace. Mentoring-at-work takes place in an organizational framework, representing a means to

facilitate career development among employees, due to its purpose for personal and professional

development of the protégé. The mentor may be a supervisor or anyone else in the company which is

outside of the command chain of the protégé, or a person from another organization. (Eby, Allen, Evans,

et al., 2008)

Recognising mentoring as a mechanism of important knowledge transfer within organizations has

increased significantly in the last years, the literature focusing in particular on the manner in which the

mentor/protégé relationship is built, on the behaviour expected from mentors, as well as on the

identification of mentorship functions. (Swap, et al., 2001, p. 99)

People with experience in an organization can help newcomers or novices to interpret the events,

understand the technological and business processes and to identify the values and norms of an

organization. In Houde’s opinion (1995), the mentor is perceived as fulfilling the following duties (St-

Jean, & Josée, 2009, p. 4):

Receiving the protégé in the working environment; Guiding the protégé at work by presenting norms, values and taboos of the organizational culture; Teaching the protégé; Training the protégé to acquire the specific skills necessary for carrying out activities specific for a

workplace;

Favouring the protégé’s promotion in the work environment; Being the protégé’s model; the later must identify with his mentor, prior to differentiate from him; Presenting a series of challenges to the protégé and offering him the opportunity to prove his skills

in solving them;

Advising the protégé regarding certain issues; Providing direct useful and constructive feedback; Morally supporting the protégé, especially in times of stress.

In order to fulfil these functions, mentors (BioTalent Canada, 2014, para. 5):

assesses the strengths, development needs and personality of the protégés, using their skills to adapt the mentoring to the person they supervise;

clearly specify their requirements, helping protégés to decide what they want from this relationship and what they need;

also understand that mentoring is an interactive process: the learning experience takes place in both directions;

help protégés to focus on clear and realistic objectives, that seek mastering of a task or solving a problem;

sharing knowledge and experience, being willing to give and receive feedback and help protégés to improve and to correct the manner in which they work;

as protégés achieve their goals, mentors help them establish new ones, assigning new tasks and responsibilities so as to continue to gain experience in different areas;

encourage protégé to take advantage of learning opportunities outside the company, sending them to others who can help them to acquire knowledge and skills relevant to their position.

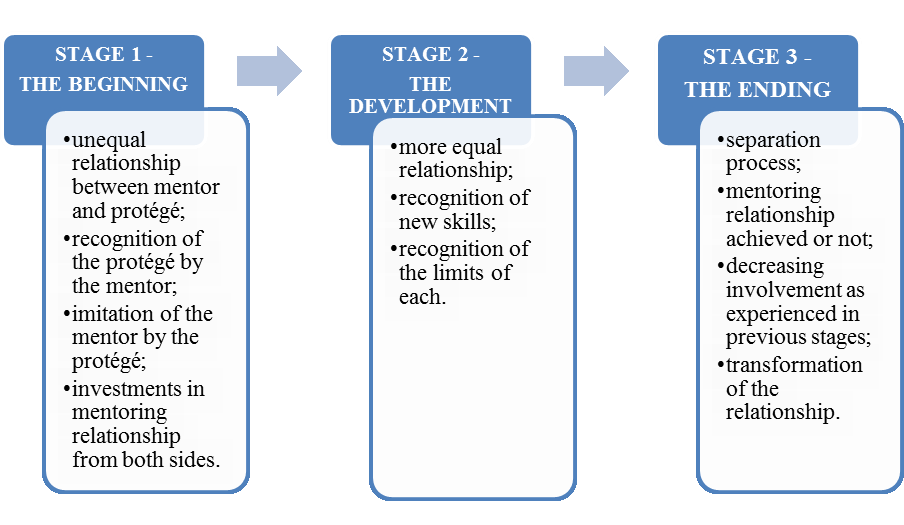

Mentorship can be seen as a gradual process in three stages, each involving specific aspects (Fig. 2).

Source: Brunet, Y. (2009). Élaboration d’un guide d’encadrement pour le mentorat auprès du personnel enseignant débutant

The Benefits and Disadvantages of the Mentoring

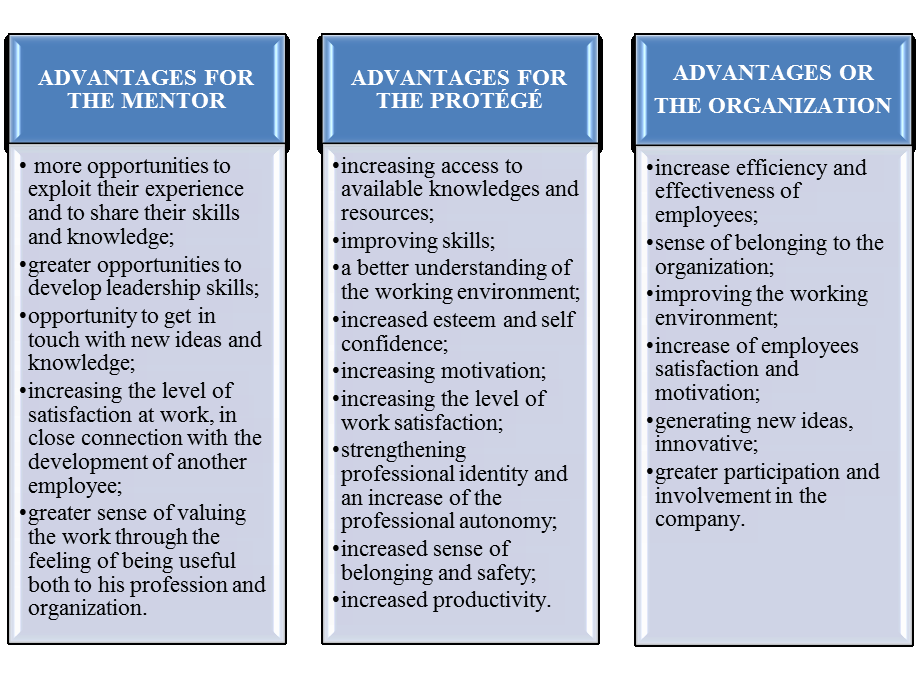

The benefits of mentoring are analyzed through increased workplace satisfaction and through

employee retention. Numerous studies have shown that people who have benefited from mentoring

perform better and promote faster, in part because they have acquired knowledge and teachings from their

mentors. (Swap et al., 2001, p. 99) The Chartered Accountants of Canada reported in their work that an

USA study on mentoring revealed the following benefits:

- 25% of employees who participated in a mentoring program changed the pay scale for a more

advantageous environment. At the opposite pole, only 5% of those who did not participate in such a

program could accede to a more favourable salary grid;

- Mentors have won promotion six times more often than those who did not participate in a mentoring

program;

- Protégés were promoted five times more often than those who did not participate in a mentoring

program;

- The retention rates were also higher for the protégés (72%) and mentors (69%) than employees who

did not participate in a mentoring program.

Source: Grenier, J.A. (2014). Mentorat – Nouvel employé UMCEP and Bureau de l’alphabétisation et des compétences essentielles. Mentorat et compétences essentielles. Retrieved from http://www.edsc.gc.ca/fra/emplois/ace/docs/outils/mentorat.pdf, consulted on 15.05.2016.

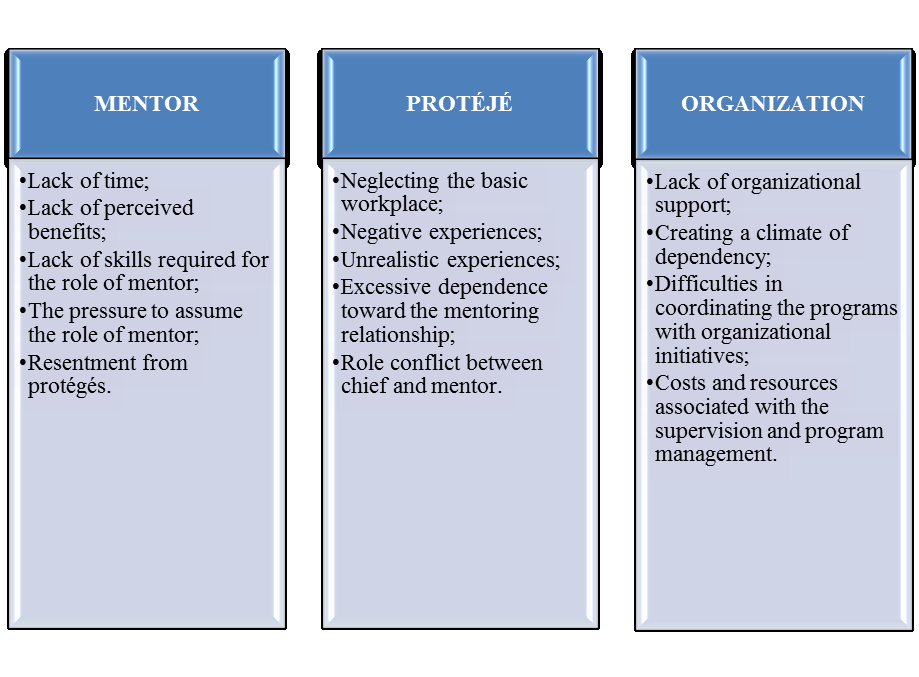

Although mentoring proves that is bringing many benefits to all organizational participants, Long

(1997, p. 115) points out that it may have a “dark side” and that although the general picture is a bright

side of wonders that mentoring can do, especially for the professional development of staff, at least some

scholars and practitioners are sceptical. In fact, in different circumstances, mentoring relationships may

actually be detrimental to the mentor, the protégé or to both of them.

The major concerns in terms of mentoring include those under which mentoring is time-

consuming for all parties involved, the mentoring process can be poorly planned, an unsuccessful

assignment between mentors and protégés can be made, leading to a weak relationship between mentor

and protégé, a lack of understanding of the mentoring process may appear, the mentoring can create

tensions in the workplace, there may be an over-utilization of available mentors, the protégé may

reproduce the mentor’s work style. (Ehrich, &Hansford, 1999, p. 102)

Another problem mentors may face is the lack of support for professional development. In

companies, employees are selected to be mentors as they are qualified for the jobs they occupy, however,

mentorship requires different sets of skills and, thus, many mentors face difficulties regarding the high

demands of the role, not having sufficient experience as to deal with it. Several authors have raised the

issue of security-at-work, citing the Japanese mentoring, which expects for more experienced workers to

support the development of beginner staff, being in the same time protected against the possibility that

protégés take their positions. Furthermore, it is considered necessary that employees benefit from paid

free time to learn how to be effective mentors. (Holland, 2009, p. 20)

Figure

Source: Douglas, C.A. (1997). Formal mentoring programs in Organizations. An Annotated Bibliography, Centre for Creative

Leadership, Greensboro, NC, p. 86.

In conclusion, we can say that despite grey aspects, imminent for any process, mentoring, as a

means to help employees improve their skills and essential abilities, is a win-win process, in which all

parties can gain precious advantages, and mentors, whether or not formally appointed, serve as informal

teachers, their knowledge being successfully transferred.

Conclusions

Nowadays, work is proving to be more competitive than ever, the war for talents making their

presence felt more strongly. (Bolser,& Gosciej, 2015, p. 7) In this context, it emerges as a major

opportunity for the companies to use labour to meet these challenges through mentoring, which proves to

be beneficial for both the employer and the employee. (Ray, 2015, p. 23) A formal and structured

relationship between a mentor and a protégé is an alternative approach or an original addition to

traditional methods of training and career management. (Benabou, &Benabou, 1999)

Mentoring fosters a culture in which employees are considered to be lifelong learners, this

collaborative approach going beyond generations and hierarchies, with an essential role to facilitate a

faster transfer of valuable tacit knowledge throughout the organization.

As highlighted by Oxford Economics in its report, the value of learning in the workplace can be

clearly translated in that it leads to benefiting from well-trained employees, with constantly updated skills

and knowledge, essential aspects for building stronger companies. Despite these issues and although

employees require more education and development opportunities, and managers recognize the

importance of training their employees, learning culture remains a sensitive area for most companies. By

providing more opportunities for training and skills development and by promoting an environment

where sharing knowledge is encouraged and rewarded, companies will have superior opportunities to

thrive in a world belonging to this century, focused on information.

References

- ADASUM. (2015). Guide pour les mentors et mentorés : Qu’est-ce que le mentorat, Montréal, Québec. Retrieved from http://adasum.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Quest-ce-que-lementorat.pdf.

- Allen, T.D., & Eby, L.T.(2007). The Blackwell handbook of mentoring : a multiple perspectives approach, Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Benabou, C., & Benabou, R.(1999). Establishing a formal mentoring program for organization success, National Productivity Review, 18(2), 7-14.

- BioTalent Canada (2014, November). Les 10 qualités de tous mentors efficaces. Retrieved from https://www.biotalent.ca/fr/article/les-10-qualit%C3%A9s-de-tous-mentorsefficaces#sthash.KIioyQw5.dpuf.

- Bolser, K., & Gosciej, R. (2015). Millennials: Multi-Generational Leaders Staying Connected, Journal of Practical Consulting, Vol. 5 Iss. 2, 1-9. Retrieved from http://www.regent.edu/acad/global/publications/jpc/vol5iss2/BolserGosciej.pdf.

- Brunet, Y. (2009). Élaboration d’un guide d’encadrement pour le mentorat auprès du personnel enseignant débutant en soins infirmiers au collégial, Université de Sherbrooke.

- Bureau de l’alphabétisation et des compétences essentielles. Mentorat et compétences essentielles.Retrieved from http://www.edsc.gc.ca/fra/emplois/ace/docs/outils/mentorat.pdf.

- Source. Webinar Series. Retrieved from Chartered Accountants of Canada. CA http://www.snwebcastcenter.com/data/2854/support_doc/4970369A%20CA%20Source%20I mpact%20Mentoring-F.pdf.

- Council of the European Union (2011). Council Resolution on a renewed European agenda for adult learning (2011/C 372/01), Official Journal of the European Union. Retrieved from http://eurlex.europa.eu/legal-content/RO/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32011G1220(01)&from=EN.

- Cuerrier, C. (2003). Le mentorat et le monde du travail au Canada : recueil des meilleures pratiques, Québec, Éditions de la Fondation de l'entrepreneurship, coll. Mentorat.

- Douglas, C.A. (1997). Formal mentoring programs in Organizations. An Annotated Bibliography, Centre for Creative Leadership, Greensboro, NC.

- Eby, L.T., Allen, T.D., Evans, S.C., et al. (2008). Does Mentoring Matter? A Multidisciplinary Meta-Analysis Comparing Mentored and Non-Mentored Individuals, J Vocat Behav, 72(2):254–267. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2352144/?__hstc=245426011.96ec071bae4c3 d40c40ec7d57cd5d75b.1415232000097.1415232000098.1415232000099.1&__hssc=2454260 11.1.1415232000100&__hsfp=2439899863.

- Ehrich, L.C., & Hansford, B. (1999). Mentoring: Pros and cons for HRM, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 37(3), 92-107.

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop) (2011). Learning while working, Success stories on workplace learning in Europe, Luxembourg.

- Retrieved from Eurostat. Vocational education and training statistics.

- http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-

- explained/index.php/Vocational_education_and_training_statistics#Further_Eurostat_informat ion.

- Eurostat Database. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/education-and-training/data/database.

- Grenier, J.A. (2014, January). Mentorat – Nouvel employé UMCEP.

- Holland, C. (2009). Workplace Mentoring: a literature review, Auckland, New Zeeland:Industry Training Federation. Retrieved from https://akoaotearoa.ac.nz/download/ng/file/group-4/n3682-workplace-mentoring---a-literature-review.pdf.

- Houde, R. (1995). Des mentors pour la relève, Méridien.

- Leloup, L. (2014, November 26). Le monde du travail en 2020: une crise des talents imminente.

- Retrieved from http://www.finyear.com/Le-monde-du-travail-en-2020-une-crise-des-talentsimminente_a31167.html.

- Long, J. (1997). The dark side of mentoring, Australian Educational Research, vol. 24, no. 2, 115-83. Oxford Economics. Workforce 2020. The Learning Mandate. Retrieved from http://www.oxfordeconomics.com/workforce2020/reports.

- Ray, K. (2015). Mentoring the next generation – developing future talent, The OCM Coach and from Mentor Journal, 20-23. Retrieved http://www.theocm.co.uk/sites/default/files/documents/resources/Mentoring_the_next_generat ion_OCM_Journal_2015.pdf St-Jean, É., & Josée, A. (2009). Proposition d’un outil de mesure des fonctions du mentor de l’entrepreneur. Retrieved from http://www.fsa.ulaval.ca/sirul/2009-011.pdf Swap, W., Leonard, D., Shields, M., Abrams, L. (2001). Using Mentoring and Storytelling to Transfer Knowledge in the Workplace, Journal of Management Information Systems , Vol. 18, No. 1, 95-114.

- Tynjälä, P. (2008). Perspectives into learning at the workplace, Educational Research Reveiw 3, 130-154.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Brînzea, V., & Oancea, O. (2017). The Mentoring, a Successful Way to Develop Skills, in the Modern Society. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1337-1345). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.164