Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to know the set of ideas that students associate to various disruptive behaviours developed in classroom space. A practical motivation: the need to know the system of beliefs that students develop relate to a set of behaviours which are not missing from the specific experiences of classroom’s life. The necessity is supported by the importance of these beliefs: they represent the most relevant source of the behaviours in the space of classroom. Paper is motivated also by the desire to address the behaviours analysed from a pedagogical perspective rather than psychological. Usually, undesirable behaviours of students are called deviant behaviour, with reference to the more or less relative to normality criteria. This is a psychological approach emphasized. The disruptive behaviours try resizing perspective into a pedagogical one. The applicative investigation was shaped around the aim: to configure an image that different types of students associate to different disruptive behaviour that they meet in classroom. Was used a questionnaire (for students) to find out what they think about each disruptive behaviour (how upsetting they believes that behaviours are, what are the causes, how teachers should react, which should be the reaction of colleagues). The number of questioned students is 60. Seven and eight grade (30 students of each). Two differentiating criterion were applied: gender and learning results (good and struggling students).

Keywords: Truancyhomework plagiarizeverbal aggressiontest plagiarize

Introduction

The disruptive behaviour is a manifestation that contradicts all the school collectivist’s rules. More

precisely, it is a undesirable behaviour with a negative influence on the school learning activity, including

the relations and the interpersonal attitudes, while deviant behaviour are often understood as behaviour

disorders. This is the reason why specialists think that diagnose of the deviant behaviour is possible considering statistic and medical criteria, as well as social reactions and magnitude. The points of view

are so fluid, so a reflexive debate is necessary. The frequency of behaviour which obstructing the

teaching-learning process is a reality that cannot be ignored. Regarding disruptive behaviour, the main

intention was to differentiate it by the deviant one. The set of disruptive behaviours is divided into:

disruptive behaviours manifested in relation to the learning activity (called academic) and disruptive

behaviours manifested in relation to others, colleagues and teachers (called social/relational). Regarding

students’ representations, the intention was to achieve a comprehensive picture on issues such a personal

products that have a strong social source. This image will help to build a personal attitude towards the

reflected phenomenon.

Paper Theoretical Foundation and Related Literature

A deviant behaviour is a significant distance from the general rules in a school. Deviation can be

seen as a social construct and not as a feature linked to a certain manifestation, being a consequence of

rules and sanctions applying. For Blândul (2012, p.13) the deviant behaviour is “the result of a label the

others put on a person”. Very often, the scientific literature speak about behaviour disorders as deviant

behaviours. The criteria is always the same: complying to the behavioural rules, rules understood as “all

the habits, conventions, rules or interdictions claimed by society at certain point” (Rădulescu, 1998, pp.

17-18).

Yet, the rule is relative because the cultural differences between individualities, so it is difficult to

frame all the human behaviours. The closest concept for the behaviours disorder is school deviance

defined as ”all the students’ behaviours through which they violate the school values and rules” (Blândul,

2012, p. 41).

The authors have different perspectives regarding this issue. For some of them the topic is about

the disciplined behaviour; for example, Glava & Glava (2000, 174) see it as ”the assimilation of values

regarding responsibility, growth of self-esteem, respecting chance equality and dignity, polite, tolerance,

trust in each other, perseverance”.

Others report it to the educational crisis (Pânişoară, 2009). Or to the school adaptation phenomena,

defined as ”the student’s ability to identity adequate answers to the school environment or new school

situations demands. So, adapting to school (and having success) is not only about academic performance,

it also includes the aspects of a real social life inside school” (Jigău, 1998, p.92). More, same authors

reveal the bright side of the behavioural problems or disorders (if shown in certain limits, of course)

(Neamţu, 2003, p.31):

-Behavioural problems can be an indicator for the teacher that the student finds the situation

threatening or unacceptable;

-Behavioural problems can be an indicator that the rules are not working and should be replace

with more adequate ones.

-Bad behaviours can indicate a students’ disguise protests related to a certain situation generated

by the teachers;

-Last, the presence of behavioural problems amongst students could show their need to be

activated, implicated, or their need for the adults or teacher’s attention.

Methodology

Was used a questionnaire to find out what the students think about each disruptive behaviour (how

upsetting they believes that behaviours are, what are the causes, how teachers should react, which should

be the reaction of colleagues). The number of questioned students is 60. Seven and eight grade (30

students of each). Two differentiating criterion were applied: gender and learning results (good and

struggling students). The answers were distributed on four level of a Likert scale: not irritating, less

irritating, irritating, very irritating. This distribution help the operationalization act. In this paper it was

analysed two types of disruptive behaviours: the first of them refers to behaviours academic significance

(in relation to school work) and the second with social significance/ /interpersonal (in relation to teachers

and colleagues). Disruptive behaviours manifested in relation to the learning activity (called academic):

homework plagiarize, test plagiarize, chat during class, truancy, do not do homework, parallel activities,

and have not the appropriate tools and materials. Disruptive behaviours manifested in relation to others,

colleagues and teachers (called social/relational): demonstrative behaviour, verbal aggression, bullying,

physical aggression, impolite.

Results

4.1.Academic Disruptive Behaviour

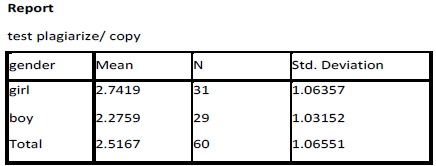

moderate in terms of intensity: 0,319 at 0.05 significance level. This means that girls think this kind of

behaviours more upsetting. Concerning the ”school results” criteria, the correlation is not only

statistically significant, but also in terms of intensity: 0.594, at 0.01 significance level. The students with

good results find homework plagiarising more upsetting. Concerning the ”class” criteria, the statistics do

not show any difference between the two categories of students.

”school results” , the correlation is significant statistic: 0.773, at a 0.01 significance. The students with

good results find test plagiarising more irritating. The ”class” criteria it is not associated with differences

between the two categories. Depending the criteria “gender”, the image shows as below:

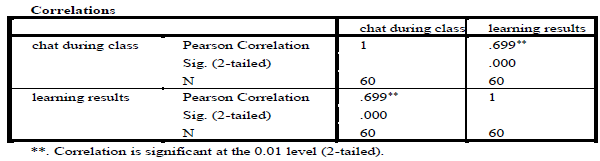

”chat during class”. Concerning ”school results” criteria, it is significant statistic correlation, at a .01

significance level.

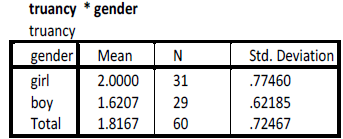

significance level; girls are more disturbed by this behaviour. There also is a significant correlation

(0.394) between ”school results” and ”truancy”, significance level: 0,01. We have reason to say students

with good school results are more disturbed by this behaviour than the other students.

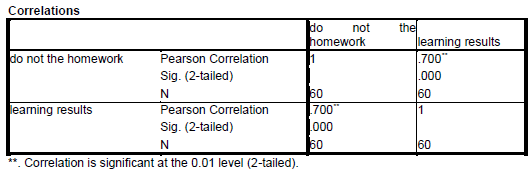

statistic correlation , but a moderate one (0.300), at 0.05 significance level: the seven grade student are

more disturbed by this behaviour than the eighth grade student. Relating the ”gender” criteria, it is not a

significant statistic correlation with this behaviour. But, the students with good results find the behaviour

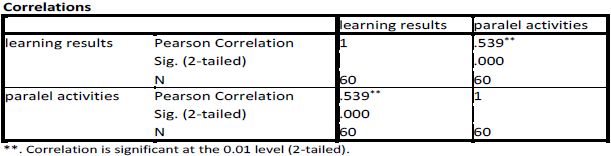

more irritating:

behaviour, at 0.05 significance level: girls are more irritated by this behaviour. Relating ”school results”

the illicit behaviour correlate “better”:

4.2. Social Disruptive Behaviour

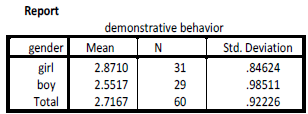

”school results” criteria (0.383) (significance level: 0,01). For the ”class” criteria, the correlation is

stronger: 0.419: the seventh grade students are more disturbed by demonstrative behaviour than the eighth

grade students. A short and interesting image of the answers’ by gender:

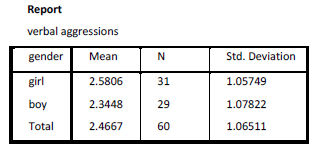

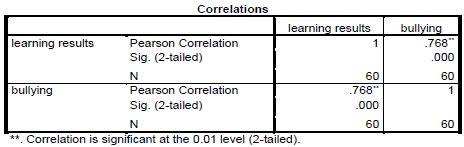

by 0.01. Is not a significant correlation between this behaviour and the ”gender” and ”class” criteria; but a

visible homogeneity need attention:

significance level of 0,01:

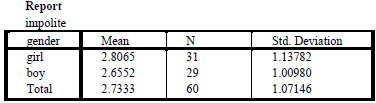

moderate. For the ”school results” correlation is 0.471, at 0.01 significance level. So, the impolite become

a more troublesome behaviour as learning results are better. An interesting information: the values for

the means, by the criterion “gender”:

Discussions

At the academic level of disruptive behaviour, finds that the level of academic results is the

variable that correlates most significant and more frequently. The fact that students with good academic

results compared to lower achieving students feel these behaviours as being irritating, confirms motivated

attitude the first for a school environment as healthy as possible. Thus, students with higher academic

results disapproving react to the emergence of behaviours that impede learning activity. Noteworthy,

there are two behaviours that are not as troublesome as the other: truancy and speaking in class. This

attitude can express some level of copying (when speaking in class), and a relatively natural indifference,

the lack of personal effects (at truancy).

Regarding the gender criterion, three are considered real irritating behaviour: cheating homework,

truancy and parallel activities. Girls tend to evaluate these behaviours as troublesome. For the first

situation (copying homework), the explanation might be: are those who make their theme, they are asked

by colleagues to offer their own theme as a model. Do not make your theme is not considered, by girls,

annoying behaviour itself but its effect becomes.

In relation to the criterion ”class” only one variable correlated: not doing homework. Students of

seventh grade considers the behaviour as being more irritated, compared to students of eight grade. The

study priorities determines probably the students in the last grade of secondary school to provide less

attention and significance of achieving the homework.

Regarding the social-relational disruptive behaviour, the only criterion which correlate is school

performance. In other words, girls and boys have the same evaluative reactions and attitudes in relation

with all forms of aggression (verbal, physical, bullying), a prove that boys are not more indifferent to

these behaviours than girls. The same attitude is also found in relation to the criterion ”class”. In other

words, the age difference is sufficiently small for generate different attitudes.

Conclusions

The proposed study has the significance of an epistemic landmark which can be used as a

motivational resource for further investigative actions, both transversal and longitudinal studies. The

evaluative attitudes of students in relation to various behavioural realities developed in the classroom are important variables, both in classroom management, and in the learning management. Knowledge of

these attitudes has role to adjust the optimizing actions initiated by the teacher. On the other hand, this

knowledge allows the teacher to anticipate crisis situations. Because this is one of the essential challenges

of the teacher: ”Faces numerous interrogations which refers not only to the professional roles but also

refers to many skills needed to achieve a quality educational praxis” (Petre, 2012, p.7).

References

- Blândul, V. (2005). Introduction to special education, Oradea: University Publishing Blândul, V. (2012). Psychopedagogy of deviant behaviour, Bucureşti: Aramis Glava, A., & Glava, C. (2000). A Study of Differentiation and its Implications in Improving Classroom

- Achievement. In Studia Universitatis Babeş-Bolyai, Psychologia – Paedagogia, 1, (pp.172-183)

- Hăvârneanu, C., & Amorăriţei, C. (2001).Aggressiveness in teacher-student relationship. In L. Şoitu &

- C. Hăvârneanu (Eds.), Aggression in school (pp.87-112). Iași: European Institute

- Iucu, R. B. (2000).Classroom management and administration: theoretical and methodological

- foundations, Iași: Polirom Iucu, R.B. (2006). Classroom management. Applications for crisis management education, Iași: Polirom Jigău, M. (1998).Factors school’s success, Bucureşti: Grafoart Neamţu, C. (2003).Deviance school, Iași: Polirom Pânişoară, I.O. (2009). Successful teacher. 59 principles of practical teaching, Iași: Polirom Petre, C. (2012). Classroom management. Theoretical basis, Constanța: Muntenia Rădulescu, S.M. (1998). Sociology of deviance, Bucureşti: Victor

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Simion, L. (2017). The Disruptive Behaviour in Classroom. Students’ opinion. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1262-1268). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.154