Abstract

The aim of this study was to explore the relationship between preadolescents’ perception of parenting styles and identity development in a Romanian preadolescent sample. Perceived authoritative, authoritarian, permissive and neglectful parenting styles (

Keywords: Authoritativeauthoritarianpermissive and neglectful parenting styles; informativenormativecommitted and diffuse identity styles

Introduction

Adolescence is the life stage when the sense of a stable and coherent identity is achieved;

however, some adolescents may experience unclear, confuse identity (Erikson, 1968; Berzonsky, Branje,

& Meeus, 2006; Pellerone, Tolini, & Polopoli, 2016). Identity is developed through continuing and cyclic

processes of exploration and commitment (Marcia, 1966) and it have different statuses: achievement

(high commitment and high exploration), moratorium (high exploration and low commitment),

foreclosure (low exploration, high commitment), and diffusion (low exploration and low commitment).

Related to Marcia’s model, Berzonsky (1990) described three identity styles: information-oriented,

normative and diffuse-avoidant. Information-oriented individuals develop their identity by actively

seeking and evaluating relevant information before making commitments, display high levels of self-

regulated functioning (Soenens, Berzonsky, Vansteenkiste, Beyers, & Goosens, 2005). Normative

individuals shape their identities based on social norms and on expectations of significant others, organize

their behaviour on the basis of external control and constraints (Soenens et al, 2005). Diffuse-avoidant

individuals avoid identity issues and procrastinate decisions until life situations dictate their behaviour;

they are unable to effectively regulate the behaviour and are confused and uncertain about themselves

(Berzonsky, 1990; Soenens et al., 2005).

Parenting Styles

Perceived parenting styles (PS) are among the most important social factors influencing identity

formation processes (Berzonsky, 2004). The main dimensions of parental practices are demandingness

(maturity demands, supervision, discipline, and willingness to confront child who disobeys) and

responsiveness (the extent to which parents intentionally foster individuality self-regulation and self-

assertion by being supportive, attuned, and acquiescent to children’s special needs and demands)

(Baumrind, 1991). Combining high and/or low levels of responsiveness and control, four prototypes of

PS were conceptualized: authoritative, authoritarian, permissive and rejecting-neglecting (Baumrind,

1991; Maccoby, & Martin, 1983). The authoritative parents are both demanding and responsive: they give

to the child clear standards of conduct, monitor child’s behaviour but are not intrusive and restrictive;

discipline is rather supportive than punitive. Authoritarian parents are demanding and directive but

nonresponsive; they expect obedience from child, without explanations; they provide an orderly

environment and a clear set of regulations, and monitor children activities carefully. Permissive or

indulgent, nondirective parents are more responsive than demanding, non-traditional, lenient; they don’t

require mature behaviour, avoid confrontation, and allow self-regulation (Baumrind, 1991). Rejecting-

neglecting or uninvolved, disengaged parents are neither responsive nor demanding; they are not

supportive, they don’t structure and monitor child behaviour, but may actively reject childrearing

responsibilities (Maccoby, & Martin, 1983).

Relationship between Parenting Styles and Identity Formation

Parenting and identity formation are dynamically interlinked because identity is a result of person-

context interactions and transactions (Beyers, & Goosens, 2008; Luyckx, Soenens, Vansteenkiste,

Goossens, & Berzonsky, 2007). Theoretical approaches of family systems and attachment (Grotevant, &

Cooper, 1985; Bowlby, 1969) endorse the contribution of parenting rearing styles to differences in

identity exploration (see Smits et al. 2008 for review). In early adolescence and even in late adolescence,

parents keep being an important source of socialization and social support helping adolescents to

recognize and to shape their identity, even if the parenting practices changes in this stage (Beryonskz,

2004; Beyers, & Goosens, 2008; Smetana, & Rote, 2015). The breadth and depth of exploration is

conditioned by the quality of parenting; nurturing parenting promotes high quality exploration and

subsequent commitment (Smits et al., 2008). Adolescents with authoritative parents tend to develop

information-oriented identity style, while those with authoritarian parents develop normative or diffuse-

avoidant identity styles because of their fear of disappointing others and of lack of openness to ideas and

feelings; diffuse-avoidant identity was related with permissive parenting styles and with lack of

expressiveness in family communication (Berzonsky, 2004; Pellerone et al., 2016; see Smits et al., 2008

for review).

Problem Statement

As we seen above, many studies explored the impact of individual and social factors on the

identity formation in adolescence but, most of studies focused on late adolescence (Berzonsky, 2008;

Arslan, & Ari, 2010, Soenens et al., 2005; Pellerone et al., 2016; Reis, & Youniss, 2004). Moreover, the

process of identity shaping as individualisation or emancipation from origin family make sense in

individualistic, not in collectivistic cultures (Parra, Oliva, & Sanchez-Queija, 2014), as is the case of

Romania. This study aims to fill these gaps exploring the relationships between perceived PS and identity

styles in a Romanian early adolescent sample, focusing also on gender, environment and age influences.

Research Questions

This study aimed to explore the differences related to gender, age, urban/rural residence in

adolescents’ perception of PS and their identity styles and the relationships between perceived parenting

and identity styles.

Research Methods

Participants

In this study participated on voluntary basis 213 students, enrolled in 6th (40.4%), 7th (41.8%) and

8th (17.8%) grade in two secondary schools, from a city situated in North–East region of Romania.

Participants were aged between 11 and 15 years (M=13.27, SD=.88); 53.5% of participants were boys

and 77.9% were urban residents; 8.92 of respondents declared that their father lives elsewhere and did not

reported on father parenting style.

Instruments

To explore identity style, participants completed a Romanian version of the Identity Style

Inventory (ISI; Berzonsky, 1992, unpublished measure). The inventory required from participants to rate

28 scale items, from 1 (not at all like me) to 5 (very much like me). The ISI was translated into Romanian

using a committee approach. Differences in translations were discussed and disagreements were resolved

through consensus. Next, a translation–back translation procedure was used. Items were translated into

English and an independent person matched the original and the back-translated items. Correct match was

achieved for all items. Cronbach’s alpha for the information-oriented scale (11 items, e.g., ‘‘When

making important decisions, I like to have as much information as possible’’) was .61. Cronbach’s alpha

for the normative scale (7 items, e.g., ‘‘I prefer to deal with situations in which I can rely on social norms

and standards’’) was .62. Cronbach’s alpha for the diffuse/avoidant scale (10 items, e.g., ‘When I have to

make a decision, I try to wait as long as possible in order to see what will happen’’) was .70. A score was

calculated for each identity style, as arithmetic mean of the items scores. Although reliability was

moderate to low, this is in line with previous psychometric findings (Berzonsky, 1992, 2008).

Parenting Styles Scale (PSS, Gafoor, & Kurukkan, 2014) was administered to measure perceived

parental styles. The participants rated mother and father parenting style, responding to 34 items on a five

point scale, from 5 to 1 as, “always true”, “almost true”, “sometimes true, sometimes false”, “almost

false”, and “always false”. Half of the items measured the responsiveness and half of them explored

demandingness/control. The instrument yielded six separate scores (as arithmetic mean of item scores) for

each participant, namely mother’s responsiveness, father’s responsiveness, mother’s control, father’s

control, parental responsiveness and parental control. Parenting styles were calculated by reference to the

median of responsiveness and demandingness/control. If the scores of both responsiveness and control

were above mean, the parenting style was considered authoritative; if both responsiveness and control

scores were below the median, the style was categorized as neglectful; if the score was high in

responsiveness and low in control, the style was considered permissive; and if the score was low in

responsiveness and high in control, the style categorized as authoritarian. Medians for parenting

dimensions were the following: parental responsiveness (Mdn=3.92, SD=.56), parental control

(Mdn=3.32, SD=.54), maternal responsiveness (Mdn=4, SD=.57), maternal control (Mdn=3.47, SD=.53),

paternal responsiveness (Mdn=3.82, SD=.73), paternal control (Mdn=3.17, SD=.68). Cronbach’ alpha for

mother’ responsiveness scale (17 items) was .80, for father’ responsiveness scale (17 items) was .87.

Cronbach’ alpha for mother’ demandingness scale (17 items) was .71; for father’ demandingness scale

(17 items) was .80.

Findings

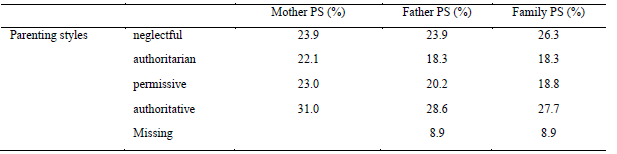

Our empirical data indicated that the most of participants perceived their parents as authoritative,

although the distribution of responses among the four styles was quite balanced (see Table 1).

The mean scores for the identity styles were: M=3.38, SD=.56 for informative, M=3.55, SD=.72

for normative, and M=3.23, SD=.7 for diffuse.

Gender differences were found in diffuse identity style: t test for independent samples indicated

that boys had significantly higher scores than girls (t(211)=2.62, p<.01). Age differences were found in

perceived maternal demandingness/control. Students from 8th grade perceived significant lower maternal

control than their colleagues from 6th (MD=-.252, p<.05) and 7th grade (MD=-.263, p<.05). In boys’

sample, significant differences were found in maternal control between 8th and 6th graders (MD=-.338,

p<.05), and no differences were found in girls sample. Differences were not found in identity styles and

perceived parenting styles depending on rural/urban environment.

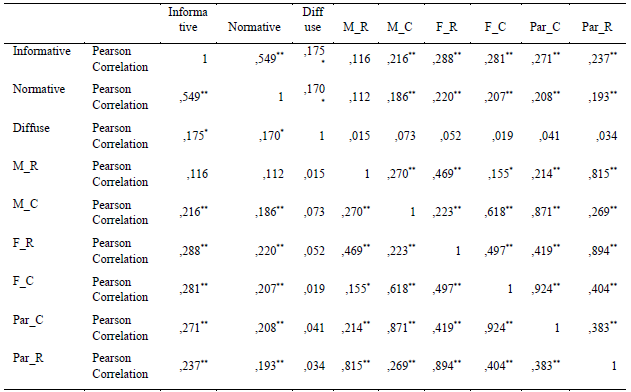

Relationships between PS and identity were explored (see Table 2). Pearson correlation indicated

significant positive relationships between informative and normative styles and parenting dimensions.

The informative and normative styles positively correlated with mother control (r=.21, p<.01; r=.18,

p<.01), paternal control (r=.28, p<.01; r=.20, p<.01) and responsiveness (r=.28, p<.01; r=.22, p<.01) and

with parental control (r=.27, p<.01; r=.20, p<.01) and responsiveness (r=.23, p<.01; r=.19, p<.01).

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

M_R - mother responsiveness, M_C - mother control, F_R - father responsiveness, F_C - father control Par_C - parental control, Par_R - parental responsiveness, participants reporting on mother N=213, participants reporting on father N=194.

Anova indicated a significant effect of PS (F=4.31, p<.01) and grade (F=4.02, p<.05) on

informative identity. Tukey post-hoc test indicated that higher scores in informative style had 7th graders

than 6th graders (MD=.199, p<.05), and students with authoritative parents than students with neglectful

parents (MD=.353, p<.005). Mother (F=2.52, p<.05) and father (F=2.77, p<.05) parenting styles also

separately influenced informative style: students with authoritative mothers (MD=.303, p<.05) and

fathers (MD=.417, p=0) obtained higher score in informative style than those with neglectful mothers and

fathers. The normative style was influenced by gender (F=10.05, p<.005) and by interaction between

parental style and grade (F=2.47, p<.05). Students with authoritarian parents from 7th grade obtained

lower score in normative style than those from sixth and eighth grade; students with permissive parents,

enrolled in 7th grade, obtained higher score in normative style than students enrolled in 6th and 8th grade.

The normative style was higher in 8th graders with authoritarian parents and in 7th graders with permissive

parents (Fig. 1.)

Tukey post-hoc test showed that, in general sample, students with authoritative and permissive

parents obtained higher scores in normative style than students with neglectful parents (MD=.363, p<.01;

MD=.363, p<.05).

Normative style was influenced by the interaction between environment and maternal PS (F=2.88,

p<.05), and between grade and maternal PS (F=2.37, p<.05). Students from rural environment with

permissive and authoritarian mother PS had higher scores than their counterparts from urban environment

in normative style, while students from rural environment with authoritative parents had lower score in

normative style than their counterparts from urban environment (Fig. 2.).

Students with authoritarian mothers enrolled in 7th grade obtained lower score in normative style

than 6th and 8th graders, while students from 7th grade with authoritative and permissive mothers obtained

higher score than students from 6th and 8th grade; in 8th grade, higher score obtained students with

authoritarian mothers, while in 7th grade those with permissive and authoritative mothers (Fig. 3.).

The diffuse identity style was influenced by the interaction between gender, environment and

parenting style (F=3.1, p<.05), and by the interaction between gender, environment and father parenting

style (F=2.66, p<.05).

Discussion

This study explored the relationship between PS and identity styles in a sample of Romanian

preadolescents. The distribution of perceptions on the four PS indicated that almost a third of participants

view their parents as authoritative, but also that a quarter of them feel neglected by their parents. The

relatively high ratio of preadolescents perceiving their parents as neglectful may raise problems in

achievement of a positive oriented identity (Luyckx et al, 2007).

In our sample, the highest mean score in identity styles were in normative, which indicated the

preference for many of our participants to conform to social rules when making decisions which; this

result could be explained through collectivistic cultural background and through participants’

developmental stage (Pellerone et al., 2016). The lowest mean score was in diffuse identity; boys

obtained significant higher score than girls in this style, which is in line with other earlier findings

(Soenens, et al., 2005; Berzonsky, 1992). 7th graders had higher scores in informative style than 6th

graders, which suggests that this style gain greater importance with age, confirming previous findings

(Berzonsky, 2008), but this trend wasn’t maintained in 8th grade, which is a stage where students have to

make important choices for their educational and career orientation.

Perception on maternal control was dynamic. In general sample and in boys, older students

perceived less maternal control than their younger colleagues. As Smetana & Rote (2015) indicated, the

maternal control on the adolescent boys declines more sharply, because of lower willingness to discuss

private aspects with their mothers, and because of fear of parental disapproval.

In our sample, higher scores in informative style obtained students with authoritative parents than

students with neglectful parents; higher normative style showed students with permissive and

authoritarian parents than those with neglectful parents. Respondents from rural area with authoritarian

and permissive mothers had higher scores in normative style than respondents from urban settings, which

indicate maybe the more restricted access to information of preadolescents from rural and more

submissive attitude in their relationships with parents. Early adolescents shape their identity relying both

on autonomous processing of information and on social norms imposed by parents; as Parra et al. (2015)

highlighted, in high cohesive families where the relationships with parents are very close, the emotional

autonomy is not encouraged, and the normative style tend to develop more. Our findings may be

explained also by the need of adolescents from collectivistic cultures to meet parental and social

expectations (Pellerone et al., 2016). In our sample the obedience to rules was higher when

preadolescents perceived higher responsiveness or higher control, and not equilibrium between them.

Conclusions

Although these results can’t be generalized because of relatively small number of participants,

however they endorse the importance of authoritative parenting style and the role of fathers in assisting

early adolescents to shape information–oriented identities. Also, these findings signal the need of more

attentive preoccupation of parents to balance responsiveness and control in conducting socialization

processes. The high scores in normative style could depict just a temporary early phase in the identity

development, or could signal a persisting tendency, to rely own identity decisions on social norms and

expectations rather than on exploring and processing relevant information. Facilitating in school the

access to relevant information and autonomous decision making processes can encourage the information

identity style development.

References

- Arslan, E., & Ari, R. (2010). Analysis of ego identity process of adolescents in terms of attachment

- styles and gender, Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2, 744-759.

- Baumrind, D. (1991). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. Journal

- of early adolescence, 11(1), 56-95.

- Berzonsky, M. D. (1990). Self-construction over the life span: A process perspective on identity

- formation. Advances in Personal Construct Psychology, 1, 155–186.

- Berzonsky, M. D. (1992). Identity style and coping strategies. Journal of Personality, 60(4), 771-788.

- Berzonksy, M. D. (2004). Identity style, parental authority, and identity commitment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33, 213–220.

- Berzonsky, M. D., Branje, S., & Meeus, W. (2006). Identity processing style, psychosocial resources, and adolescents’ perceptions of parent-adolescent relations. TheJournal of Early Adolescence, 27(3), 324-345.

- Berzonsly, M. D. (2008). Identity formation: The role of identity processing style and cognitive

- processes, Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 645-655.

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

- Gafoor, A. K., & Kurukkan, A. (2014). Construction and validation of scale of parenting style. Guru Journal of Social and Behavioural Sciences, 2(4), 315-323.

- Luyckx, K., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Goossens, L., & Berzonsky, M. D. (2007). Parental psychological control and dimensions of identity formation in emerging adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(3), 546-550 Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In P. Mussen (Ed.) Handbook of Child Psychology, vol. 4. New York: Wiley.

- Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551–558.

- Parra, A, Olliva, A., & Sanquez-Queija, I. (2015). Development of emotional autonomy from adolescence to young adulthood in Spain. Journal of Adolescence, 38, 57-67.

- Pellerone, M., Tolini, G., & Polopoli, 2016, Parenting, identity development, internalizing symptoms, and alcohol use: A cross-sectional study in a group of Italian adolescents, Dove press, 12, 1769-1778.

- Reis, O. & Youniss, J. (2004). Patterns in identity change and development in relationships with mothers and friends, Journal of Adolescent Research, 19(1), 31-44.

- Smetana, J. G., & Rote, W. M. (2015). What do mothers want to know about teens' activities? Levels, trajectories, and correlates. Journal of Adolescence, 38, 5-15.

- Smits, I., Soenens, B., Luycks, K., Duriez, B., Berzonsky, M., & Goosens, L. (2008). Perceived parenting dimensions and identity styles: Exploring the socialization of adolescents’ processing of identity-relevant information. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 151–164.

- Soenens, B., Berzonsky, M. D., Vansteenksiste, M., Beyers, W., & Goosens, L. (2005). Identity styles and causality orientations: In search of the motivational underpinnings of the identity exploration process. European Journal of Personality, 19, 427-442.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Butnaru, S. (2017). Perceived Parenting Styles and Identity Development in Preadolescence. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1155-1163). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.142