Abstract

The gap between theory and practice has been adressed in many studies related to teacher education programmes, all proposing different solutions to bring closer the training student teachers receive during courses to the reality of the classroom they face once they start teaching, with a focus on more teaching practice opportunities and changes in the course content. Continuous changes in the last quarter of a century affecting the Romanian educational system in general also influenced the structure and the philosophy of teacher education and changed the focus on human resources as the key of making TE more efficient. There is a general tendency among educational programmes to explore with new learning models that can ensure expert-like competencies before graduation and with the appropriate instruments to be employed by all teachers in order to make them able to adapt to all the changes they face. This paper expands on the influence of external factors such as beliefs, opinions, attitudes, professional models, towards teaching and teachers, on the way training received or delivered is perceived. It draws on previous research I conducted on an interesting manner of accomodating in an individual innovative way, the gap between old incremented beliefs and the new theories and practices presented during the teacher education programme, as an empowering tool for all teachers to use in a variety of educational contexts.

Keywords: Teacher educationreflective practicescritical and creative thinkingsystematic enquiry model

Introduction

Continuous changes in the last quarter of a century affecting the Romanian educational system in

general also influenced the structure and the philosophy of teacher education. Human resources became

the focus in the effort of making educational processes more efficient. It is argued that training should

respond to the real needs of teachers in schools, that it should be in line with the requirements of the new

European educational environment. Moreover, exploring personal beliefs and stories is considered central

to an efficient implementation of new concepts into teaching practices. There is a general tendency

among educational programmes to explore with new learning models that can ensure expert-like

competencies before graduation and with the appropriate instruments to be employed by all teachers in

order to make them able to adapt to all the changes resulting from the educational reforms.

Support and guidance are important before and after initial education as they influence the quality

of further professional development. Despite ensuring the same training conditions for all student

teachers, these carry on differently according to their individual capacities to acquire, understand and

integrate the knowledge they come in contact with (Beckett & Hager, 2000; Flores & Day, 2006; Iucu,

2005). In this context it becomes highly important to employ the appropriate means in order to maximize

students’ capacity to adapt to changes. Various studies mention that an informal learning environment

enforced by recreational activities and mobile technologies, by contrast to the academic learning

environment, attracts, stimulates and facilitates accelerated learning due to the experiences it offers

(Eraut, 2004; Hoekstra et. al., 2007).

Reflexivity, understood as an analytical process for study, comprehension, integration and

identification of solutions for learning, can become a powerful instrument in any educational

environment. Previous research (Tugui, 2011) show that reflexivity can have positive effects when

approaching changes in teacher education. Still, it is used superficially due to lack of teaching experience

and of analytical thinking (Korthagen & Vasalos, 2005). There are approaches based on the idea that

guidance by means of different instruments can lead to the development of reflective abilities for an

individual independent progress in learning (Christie & Kirkwood, 2006).

This paper expands on the influence of external factors such as beliefs, opinions, attitudes,

professional models, towards teaching and teachers, on the way training received or delivered is

perceived. It draws on previous research I conducted on an interesting manner of accomodating in an

individual innovative way, the gap between old incremented beliefs and the new theories and practices

presented during the teacher education programme.

Theoretical Background and Related Literature

National and international literature offers valuable information on the evolution of the teaching

career (Calderhead & Shorrock, 1997; Day et. al.,2007; Iucu, 2005; Potolea & Ciolan, 2003). It is argued

that training should respond to the real needs of teachers in schools, that it should be in line with the

requirements of the new European educational environment.

We are trying to reform by changing the manner we teach, the form that our classes take, but using

the same content. We tend to forget that nowadays not the amount of information we acquire makes the

difference in class, but the way teachers know how to apply their knowledge to the teaching situations

(Wagner, 2012). Our main problem as teacher trainers is the lack of practical experience that we are able

to provide our students with. It is partly the way the curriculum is built and the number of hours allocated

to the pedagogical practice, but also the way this time is used by students and the assessment

requirements that they need to fulfil. Since our student teachers enter the class without much teaching

experience, all new theories that they have acquired during classes are difficult to be applied

automatically to their teaching, since there is no time for reflection, for testing nor for reshaping (Tugui,

2011). They tend to return to old incremented practices they know so well from their school experience as

pupils (Richardson, 1996).

Teachers can filter out training interventions, or interpret input so that it fits in with their existing

personal theories about teaching and their prior experience (Fosnot, 2005). This tendency to assimilate

inputs indicates the need to uncover teacher’s implicit theories and beliefs in order to make them

available for conscious review (Schulman, 1997). A person’s set of beliefs, values, understandings,

assumptions – the ways of thinking about the teaching profession, comprise a ‘personal theory’ (Freeman

& Richards, 1996).

In this sense, teacher education needs to recognize that each student teacher has a different way of

seeing, and thus feedback in the initial education setting should focus on the thinking and the perceptions

of individual students as well as on their actions (Steffe & Gale, 1995). As for the curriculum

(Richardson, 1996) it should include ways of developing self-awareness and also of exploring each

student teacher’s interpretations of input and their classroom experience. It should be considered that

student teachers’ learning emerges from a complex of social and individual influences such as their

experience as a pupil, the development of craft knowledge through teaching experience, personality

preferences or public educational theories acquired from training or from reading (Richard & Lockhart,

1994).

One could argue that the gap between theory and practice will always be there because there is

need for time to experience, to form opinions, beliefs and attitudes that we can transfer/apply into

practice. And irrespectively of our opinions, beliefs and attitudes, we constantly need to adapt to our

students, to their needs as individuals and professionals. Therefore, any teacher education programme has

to be flexible and adaptive, in permanent contact with the school realities and teachers’ needs. At the

same time, it needs to have a higher understanding of the pupils’ needs nowadays in order to guide the

student teachers on how to respond to them.

Teacher education should encourage teachers to reflect on their personal theories and make them

explicit (as statements, metaphors, diagrams, hypotheses, plans), to compare them with those of their

colleagues and the ‘public theory’, to relate them to their practice and as a consequence, to develop new

theories (Eraut, 2004; James, 2001). This is important for their learning because, according to James

(2001) it:

• Raises teachers’ existing knowledge into consciousness

• Helps teachers examine and question their assumptions about education, teaching and learning

• Helps teachers in the long-term task of organising and clarifying their personal theories, and

assimilating new information

• Develops teachers’ critical awareness

• Allows access to and understanding of individual teachers’ theories

For these reasons, I suggest it was relevant to this study to also explore the issue of teacher beliefs

in relation to learning to teach. A psychologist perspective on learning development recognises as crucial

in the success of learning anything that learners themselves bring to the learning situation. Learning

becomes a matter of how learners interact with what it is learned in a particular situation (Bullough,

2001).

Methodology

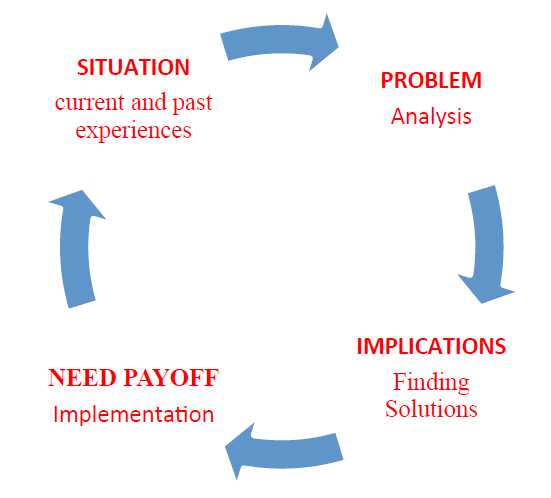

The SPIN Model represents an instrument that can assist problem identification and adaptation to

change by means of individual questions asked in a particular order. The model is the result of an

extensive research study which concluded that change can be approached efficiently through

understanding all aspects related to an issue. Any change situation involves awreness of past and current

experiences, their critical analyses which leads to acceptance and facilitates implementation of new ideas

in practice. It approches change in four steps: Situation, Problem, Implication, Need-Payoff. Because

most of the time needs are implicit, the questions of the model are aiming at making them explicit at

different levels before being able to find solutions to respond to these needs.

This model has been applied within a teacher education programme as an approach method of any

theoretical or practical issue emerging during the courses and as a criterion in the evaluation of student’s

work (reflective essays and research projects). It was used as an independent instrument employed during

existing courses and aims at determining changes in students’ performance, through de development of

reflective thinking skills. There are 60 students enrolled on this teacher education programme, whose

performance has been monitored for four semesters during their undergraduate studies and will be

watched for two more semesters in their senior year.

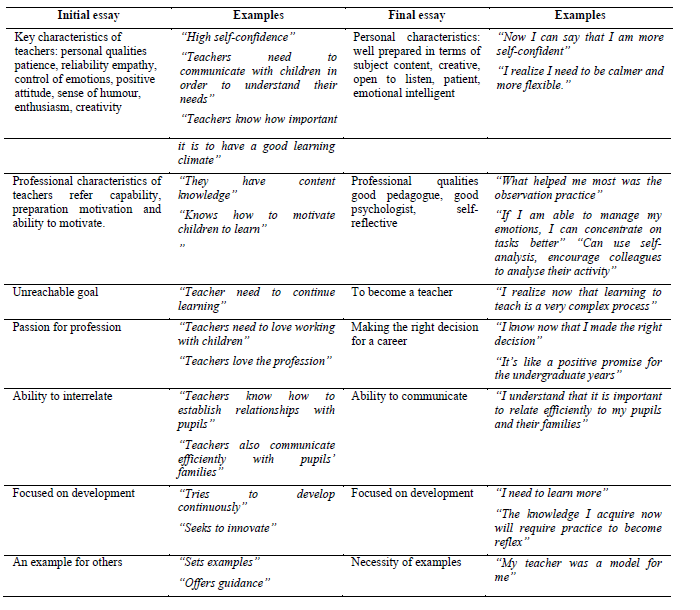

The following table shows evolution of different categories of responses from more general and

descriptive to more focused on problem solving, as collected from the initial and final essays.

In the light of the research problem posed in this article it was considered appropriate to use a

qualitative approach. The researcher was interested in improving a specific teacher education programme

and less in generalizing the findings, therefore this qualitative inquiry can be considered context-specific.

I emphasize the importance of the subjective experience of individuals and I believe that

can be related to the

understood adequately in isolation (Bryman, 2004). In this respect, the research design was flexible,

permitting interpretation and alteration. Thus, data could generate other aspects of the problematic to

investigate. The main purpose of this qualitative research is the discovery or uncovering of propositions

(Cohen et al., 2004).

Results and Discussion

Emerging data from the reflective essays showed that most of the students applied for the initial

teacher education because they liked children or working with children. For many years, initial teacher

education programmes enrolled already motivated and determined individuals, young people that

believed they had a vocation for the teaching profession. In the same way, the participants to this study

were intrinsically motivated to study to become best professional, holding a mental picture of the ideal

teacher they wanted to become.

At the same time, there was a degree of uncertainty as they were looking for a confirmation of

their career choices, for a warmer and more flexible education form that shares the same values and

attitude towards teaching. The ideal teacher, as resulting from the essays, was endowed with numerous

personal qualities such as empathy, warmth, openness, goodness, justness. This idea might have its roots

in a real need of the student for a teacher more prepared for interpersonal relationships.

It became obvious towards the end of the first year of study that it was not enough any longer to

offer them pedagogical theories, but also to help them develop a set of skills that would allow them to

manage a wider range of problems in class. It was also noticed that the style of the initial essays was quite

descriptive and ideal, lacking reflective analytical depth.

Through the course of the first year participants to the study were required to approach both their

reflective writing and academic tasks according to the steps of the SPIN model: to analyse their past and

current experiences, to find answers to the problems arising from the analysis, to take them into account

when considering others (there was no opportunity to test them in practice since there is no teaching

practice in the first year of study).

Data from further essays showed students’ writing became more analytical, as they started

admiring teachers from the initial teacher education programme more for their professional skills and

competences rather than personal attributes. This was linked to the new tools for critical analysis they had

at hand, namely the pedagogical knowledge and practical teaching knowledge they acquired through

structured observation. They applied them to the teaching situations they were part of, including their

preparation courses. This offered the means to link the academic knowledge and practice.

Other data revealed that they encountered a favourable learning context that could confirm the

choice for the profession and offered the theoretical knowledge which gave meaning to what it was

observed in class. For most of them this was a “positive promise” for the initial teacher education

programme. The majority regarded the observation practice and the theoretical courses as an effort worth

making because of the new meanings they were able to find to define/describe the pedagogical actions,

the arguments they were able to build.

The novelty this research brings is the approach to the arising issues during an initial teacher

education programme. As teacher educators we came to realise that changing issues are most of the time

context related, quite particular many times. Therefore, there was an urge to develop in our teacher

students a pattern approach that would ensure an effective critical analysis for further learning.

Conclusions

The present study proposes a new approach in educational change management and effective

learning for teaching, as a means of erasing the gap between theory and practice through structured

reflective methods. It combines principles and concepts employed in andragogy, psychology, sociology,

antropology and business in order to create efficient tool for the teacher education environment and more.

Business research uses succesfully models based on psychological and sociological theories in

training adult professionals. The transfer of such pragmatic models in teacher education can only lead

towards the creation of customised models, adapted to the requirements for the teaching profession

nowadays. Moreover, the two working environments, business and education, offer the opportunity of

exploring another theme, that of the independent learner, from a new perspective.

The results presented above are part of a larger ongoing study which seeks to improve learning

skills of student teachers at the level of their initial education in order to ensure life long learning for their

future teaching careers, and it represents only a first stage in our research.

Acknowledgements

Research project is currently being funded through the Young Researchers Grants, 2016 - Project

financed by the Research Institute of the University of Bucharest (ICUB).

References

- Beckett, D. & Hager, P. (2000). Making judgments as the basis for workplace learning: towards an

- epistemology of practice. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 19 (4), 300-311.

- Bryman, A. (2004). Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bullough, R.V. (2001). Pedagogical content knowledge circa 1907 and 1987: a study in the history of the idea. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 655-666.

- Calderhead, J. & Shorrock, S. B. (1997). Understanding Teacher Education. Case Studies in the Professional Development of Beginner Teachers, London: The Falmer Press.

- Christie, D. & Kirkwood, M. (2006). The new standards framework for Scottish teachers: facilitating or constraining reflective practice?, Reflective Practice, 7 (2), 265-276.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K. (2004). Research Methods in Education. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Day, Ch, Sammons, P., Stobart, G., Kington, A. & Gu, Q. (2007). Teachers Matter. Connecting Lives, Work and Effectiveness. New York: Open University.

- Eraut, M. (2004). Informal learning in the workplace. Studies in Continuing Education, 26, 247-273. Flores, M. & Day, C. (2006). Contexts which shape and reshape new teachers' identities: a multi-perspective study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(2), 219-232.

- Fosnot, C. (2005). Constructivism: theory, perspectives, and practice. (2nd ed) New York: Teachers

- College Press.

- Freeman, D. & Richards, J. (1993). Conceptions of teaching and teacher education of second language

- teachers. TESOL Quarterly, 27 (2), 193-216.

- Hoekstra, A., Beijaard, D., Brekelmans, M. & Korthagen, F. (2007). Experienced teachers' informal

- learning from classroom teaching. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 13 (2), 189-206.

- Iucu, R. (2005). Formarea Initiala si Continua a Cadrelor Didactice – sisteme, politici si tendinte.

- Bucharest: Humanitas.

- James, P. (2001). Teachers in Action: tasks for in-service language teacher education and development.

- Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Korthagen, F. & Vasalos, A. (2005). Levels in reflection: core reflection as a means to enhance

- professional growth, Teachers and Teaching: theory and practice, 11 (1), 47-71.

- Potolea, D. & Ciolan, L. (2003). Teacher Education Reform in Romania: A Stage of Transition. In B.

- Moon, L. Vlasceanu & L. Barrows (Eds.) Institutional approaches to teacher education within higher education in Europe: current models and new developments, UNESCO-CEPES.

- Rackham, N. (1996). The SPIN Selling Fieldbook: Practical tools, methods, exercises and resources. McGraw-Hill.

- Richards, J. C. & Lockhart, C. (1994). Reflective teaching in Second language Classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Richardson, V. (1996). The role of attitudes and beliefs in learning to teach. In J. Sikula (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 102–119). New York: Macmillan.

- Schulman, L. (1997). Professional Development: Learning from Experience. In S. M. Wilson (Ed.), The Wisdom of Practice. Essays on Teaching, Learning and Learning to Teach by Lee S. Schulman. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Steffe, L. P. & J. Gale. (1995). Constructivism in Education. New Jersey: LEA Publishers.

- Țugui, C. M. (2011). Issues of professional development based on reflective processes in ITE programmes in Romania, București: Ed. Oscar Print.

- Wagner, T. (2012). Graduating All Students Innovation-Ready. Retrieved from www.tonywagner.com/1140.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Rădulescu, C. (2017). Why Do We Mind the Gap between Theory and Practice in TE?. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 827-834). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.100