Abstract

This research is focused on the problem of older people's requirement for a convenient and comfortable accommodation and the opportunities to meet them. It was found out that motive for changes in a flat, moving to a new and more humble dwelling are caused by requirement of an old person due to the financial and physical resources. It is proved that only the social policy of the country, aimed at achieving the well-being of senior citizens will provide opportunities for moving old people into the apartment, smaller in size but comfortable, convenient, with modern conveniences and cheaper. On the basis of the conducted research it was concluded about the necessity to learn the requirement of older people in housing conditions, their desires, possibilities of self-organization and independence by homecare and paying for housing. Only on this documentary field is it possible to form a real social housing program on meeting housing requirements of older people.

Keywords: Housingwelfarerequirementopportunitypolicyprogram

Introduction

Housing plays a central role in life of people of all ages. But especially for old people whose mobility is increasingly restricted and therefore they have to spend almost all their lifetime in the apartment, it is of paramount importance that the conditions at home and in living area will meet their housing requirements. Therefore we take a look at the basic needs that are related to the housing offer.

According to the transactional view of the relationships between the person and the environment can be called the following central housing needs of older people:

the need for intimacy and withdrawal from public situations;

the need for safety, protection and security;

the need for familiarity with the spatial environment and for stability;

the need for function justice and technical reliability of the household and the household appliances;

the need for rest and regeneration;

the need for autonomy in forming the immediate surroundings;

to enable requirement, hospitality and intimate communication;

the need for sufficient space for their own personal fulfillment and for own productivity

and

the need for a positive self-presentation, for a biographical self-documentation and a symbolization of social status (representativeness)( Heinze et al., 1997).

How the accommodation can contribute to the well-being of older people largely depends on whether it allows them to satisfy these needs sufficiently. The conditions of the immediate social and spatial environment are also important for the welfare. Also old people direct specific needs for living surroundings. There are in particular mentioned here

- the need for communicatively open and spontaneous contacts of enabling environment;

- the need for clear structures;

- the need for safety by the transport and the surfaces for walking;

- the need for easy access of social infrastructure;

- the need for green areas and parks (Mackensen, 2007).

"Safe Housing"

Closely connected with the housing requirements are the motives for an exchange of the apartment, moving motives. It is first and foremost determined by older people that their willingness for moving not so high is as in their younger years. As this willingness still exists most likely in the years after retirement, the change for age-appropriate housing should also be encouraged before the seventieth years old. However, the willingness for moving is growing obviously among the elderly in recent decades (Approximately 20% of own households and 50% of rented households are replaced after 55th years according to the socio-economic panel. The research of Schader-Stiftung proves that 65% of the old households are ready for one more moving (Kremer-Preiß/Stolarz, 2003).) . The main motives of people’s willingness beyond the 65th age to move again are according to Frankfurt’s research (Schader-Stiftung, 1999) in physical condition and in health problems, followed by hope of financial discharge in particular by a low pension. Some role plays the feeling of having lived before in a very large apartment which is not a necessity at the old age. In particular, also the factor of widowhood becomes a strong incentive to replace the previous, common flat for a new more modest one.

The main hindrances for moving willingness are in the habit and familiarity with the previous apartment and its environment in particular in fear for a new environment and a loss of social contacts, but also in fear for a relocation and associated with it costs and efforts. Therefore help by moving encourages the willingness to move for many people essentially.

On the one hand the elderly search for an age-appropriate housing that ensures them long as possible independent living, on the other hand they want more contact with others and want to escape the threatening isolation and on the third hand they want to settle in case of care requirement and to do as much as possible for their safety at the old age. According to Mona Schöffler (2006) three interest types can be distinguished essentially by the moving motivated: the interest type "Independent Housing", who wants to replace the previous, mostly large apartment for an age-appropriate, to live independently and to take as little as possible advantage of help (and care); the interest type "Community Housing", who is seeking an active community life and various social and cultural offers, and perhaps is also interested in forms of communal living; and the interest type "Safe Housing", who is directed to a reliable assistance with care services and other support services in household and therefore expects a comprehensive assistance and care offer which makes a new moving in case of long-term care not useful anymore. Apartment offers for the elderly should be focused on these three basic interest types, offering a wide range of differently elaborated age-appropriate apartments (from partly adapted to one hundred percent lack of barriers), holding some forms of communal living and an interesting program of communal activities and – in accordance with different interest in care services - a compound offer of compulsory care services.

A number of social changes, that today are underlined or have already been implemented, will hit through the housing expectations of the older people in a few years. Changed attitudes are to be expected here especially by:

Increased demands for living space consumption.

Increased demands because of technological development.

Increased demands for comfort and safety.

Increased demands for autonomic designing of living space.

Demands for feasibility of new housing cultures by immigrants (Hugentobler & Huber, 2006).

A disproportionate share of female elderly and especially of long-livers.

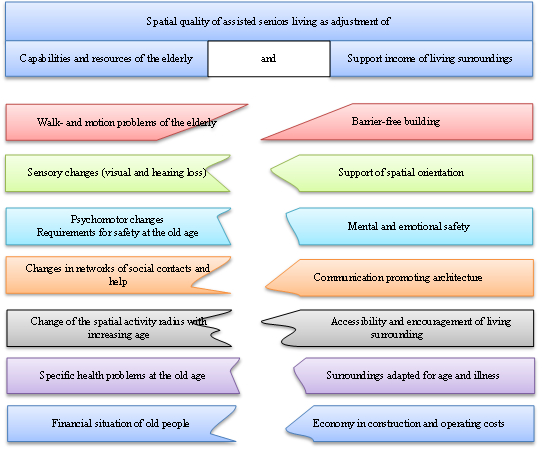

The designation "age-appropriate housing" as the objective determines from the one hand lack of lifestyle at the old age, on the other hand special requirements of the old age. Saup gives an overview about typical limitations of the capabilities and resources of the elderly and about possible responses to it because of appropriate layout of the living environment:

The aspects presented by Saup show that the architecture of the "age-appropriate housing" has to respond to a range of very different challenges of the age-specific problems and requirements. Some of these aspects will be considered again in the discussion of recommendations in Chapter 10.

The overview of Saup makes the following clear: The term "age-appropriate housing" is not open in the term "barrier-free housing". The term "age-appropriate housing" must be distinguished from the term "barrier-free housing" as well as from the term "adapted housing". First of all the term "age-appropriate housing" is the most comprising, because it refers not only to aspects of the apartment itself and access to the apartment, as another two terms, but also to aspects of the living environment. The term "barrier-free housing" is the "hardest" one, because it is determined with the German Industrial standard 18025. About "adapted" apartments we speak by all apartments, in which changes have been completed in the direction of age-appropriate housing. It is not certain in what extent these changes meet the ideal age-appropriate housing. Even small adjustments such as handles and removal of thresholds allow to speak about "adapted housing".

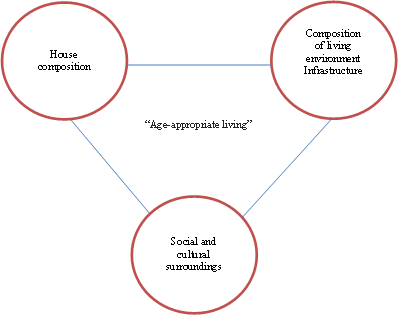

As the first the characteristics of in this context "age-appropriate housing" concern the following architectural related aspects:

the size of the apartment (reduced space requirement, clearness on the one hand, sufficient space for the use of walkers / wheelchairs on the other hand, etc.);

the number of rooms (mainly two-room apartments for single people, three-room apartments for couples, availability of a storage room, a balcony, etc.);

fitting of the apartment (handrails, emergency call systems, motorized sunblinds, adjustment to the decreased perceptual ability through higher contrast color compositions etc.);

the accessibility of the apartment (barrier-free access, elevator, etc.).

Furthermore an apartment is to different extents "age-appropriate" however, depending on, whether it allows a good supply of everyday goods or not. Therefore more quality aspects must be mentioned:

the characteristics of the residential area (infrastructure, population structure, traffic safety, social safety, opportunities for socializing, value of leisure, etc.) and

the location in a residential area (access to the shops, service offerings and leisure places, traffic connection, no infrastructure peripheral locations).

Finally, there are also social and cultural aspects that the life quality of a residential area determine, such as

social integration through a "good neighborhood climate" (avoiding loneliness);

the availability of cultural offerings, district festivals, club activities, civic initiatives and

favorable conditions for a positive identification with the district.

As the psychological analysis of living shows, housing is more than just a spatial general condition for recreation and household related activities. Living spaces are perception and orientation spaces, communication spaces that let "stage" and reveal a lot of secrets about its owner, places of the identification and symbolic representation of identity, they are places of creating and of the everyday self-setup and self-caring, they offer an opportunity to gain experience, which is withdrawn from all public, they are places of retreat and safety, of the private and intimate, and thus they have the highest emotional value. All this also has its validity for the housing for the elderly and it has architectural significance when it comes to new planning or redecorating of flats, where people want to meet their housing requirements. It is therefore important under the stipulation of "age-appropriate housing" to bring to the fore accessibility, ergonomics and other structural principles that the view of many other housing requirements will be not changed, which does not grow from disabilities and damages and are not of less importance for the life quality in the experience of old people.

In the political estimation of the "age-appropriate housing" the paramount motive is undoubtedly the search for housing forms for old people, which allow to avoid a care home for as many old people as possible and for the longest as possible period of time. This can be thereby achieved that an old person can remain as long as possible at own home or that he moves to a housing form, which is as far as required an alternative to care home. As the first it very often makes a more or less extensive rebuilding of the flat and an expansion of the facilities necessary because very few apartments in Germany are "age-appropriate" designed. However, it should be noted the orientation to the criterion of "wheelchair suitability" is far from capturing all essential aspects for age-appropriate housing. It is here in the end once referred to that much higher number of old people use a rollator walker (rollator) or a walker (in comparison to the wheelchair users); but to the movement requirements of the rollator walker was previously less significantly decisively responded as to the wheelchair.

Conclusion

This political objective is connected with psychological requirements for conservation of independence at the old age. It is not therefore done to create the structural conditions for an adequate living reality for the elderly; social and cultural offers must be rather created, which keep the elderly active and engaged, support their social networks or call the new ones into life and ensure a strengthening of self-help potential of old people. Therefore "age-appropriate housing" is also a socio-political program and it needs specific local conceptions that - parallel to constructional renewal- bring together the existing social and cultural resources with the structural reality of an accommodation into a fruitful relationship.

References

- Heinze, R.G. a.o. (1997). New apartment also at the old age. Conclusions from demographic change for housing policy and housing services. Darmstadt: Schader-Stiftung. (in German)

- Hugentobler, Margit &Huber, Andreas. (2006). Demographic change: Challenge for the housing market. Retrieved from http://web.novatlantis-ch/pdf/hugentobler-gross.pdf (in German)

- Kremer-Preiß, U. & Stolarz, H. (2003). New housing concepts for the age and practical experience by the implementation - inventory analysis. Interim report within the framework of the project "Living and dwelling at the old age" of Bertelsmann Foundation and KDA. Cologne. (in German)

- Mackensen, Eva. (2007). Dwelling in the city and demographic change. Questions to urban planning. Baum, Detlef (pub.): The city in social work. Handbook for social und planning professions. Wiesbaden: VS. (in German)

- Saup, Winfried. (2003). Assisted senior housing in reprehension of dwellers. Results from the Augsburg longitudinal study. Augsburg. Publishing house for Gerontology, Alexander Möckl. (in German)

- Schader-Stiftung (pub.). (1999). Housing wishes and housing requirements of older people in the north-western city. Result report of qualitative research. Darmstadt. (in German)

- Schöffler, Mona. (2006). Housing forms at the old age. Lahr. Kaufmann. (in German)

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

17 January 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-018-1

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

19

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-776

Subjects

Social welfare, social services, personal health, public health

Cite this article as:

Krieger, ., & Zasukhina, A. (2017). Welfare, Housing and Changed Housing Requirements of Old People. In F. Casati, G. А. Barysheva, & W. Krieger (Eds.), Lifelong Wellbeing in the World - WELLSO 2016, vol 19. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 377-382). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.01.51