Abstract

Gender-communicative competence is a vital aspect of effective pedagogy. Promoting gendercommunicative competence requires understanding pedagogical differences related to teacher gender and their impacts on students. To develop bases for the improvement of teachers' pedagogical dialogue styles that actively consider the impact of teacher gender and to outline an effective approach to improve teachers' gender-communicative competence. This study systematically compared domestic and foreign research on gender differences in communication styles. A questionnaire was used to identify differences in perception and approach among male and female teachers. 45 participants were re-surveyed after taking part in a pilot gender-communicative competence workshop. 80 Almaty students were also surveyed on their relationships with male and female teachers. While international research points to gender having a significant impact on pedagogical style and effectiveness, teachers of both genders trained in gender-sensitive communication can be effective and inspiring teachers for students of both genders. Survey results showed that Kazakhstani teachers responded well to training in gendercommunicative competence. This study systematically conceptualized gender differences in communication styles to make a model of gender-communicative competence that included axiological, cognitive and technological components. A 10-hour program was developed to improve the style of teachers' pedagogical dialogue through the formation of gender-communicative competence. The program was tested with compulsory schoolteachers working in Almaty. Forty-five teachers attended the experimental session.

Keywords: Communication StyleGender-Communicative Competence

1.Introduction

A gender imbalance favoring female teachers exists internationally and at all levels of compulsory

education. In Kazakhstan, data reported by Senate Deputy M. Bahtiyaruly indicates that in 2012,

Kazakhstan’s 7,968 secondary schools employed 292,000 teachers. Of these, 234,000, or 80%, were

women (Usupova A., 2012). As elsewhere, knowledge or convictions that certain differences in

pedagogical communication can result due to teacher gender difference has led to concerns that

Kazakhstani students’ education might be adversely affected by the imbalance. This study reviews extant

research on the specific effects of gender difference on pedagogical effectiveness, identifies differences in

perceptions and approach to gender-communicative competence among Kazakhstani teachers through a

survey, and makes recommendations to improve Kazakhstani teachers’ gender-communicative

competence and improve the efficacy of their pedagogical strategies.

2.Problem Statement

Schools with teacher gender parity are rare. The feminization of the teaching profession is a

globally relevant trend.

3.Research Questions

What are the characteristics of any differences according to teacher gender in how pedagogical

styles of communication are expressed? Is it necessary to take gender into account when teaching

students?

4.Purpose of the Study

To develop bases for the improvement of teachers' pedagogical dialogue styles that actively consider the

impact of teacher gender and to outline an effective approach to improve teachers' gender-communicative

competence.

5.Research Methods

This study systematically compared domestic and foreign research on gender differences in

communication styles. A questionnaire was used to identify differences in perception and approach

among male and female teachers. 45 participants were re-surveyed after taking part in a pilot gender-

communicative competence workshop. 80 Almaty students were also surveyed on their relationships with

male and female teachersPlease replace this text with context of your paper.

6.Definitions

and colleagues aimed toward achieving certain educational goals.

dialogue forms a definitive part of their career. Various pedagogical communication

techniques, styles of engagement, creative features, attitudes toward pupils, and adjustments

for student-teacher ratios determined by myriad settings characterized as defining styles of

pedagogical dialogue.

7.Conceptions of Gender Differences in Pedagogical Communication

Several studies on the impact of gender differences on pedagogical communication have yielded

multiple insights for developing models of gender-communicative competence.

7.1.The Hypothesis of Attraction (SAH)

Roxana Moreno and Terri Flowerday's study (2006) on the hypothesis of attraction focused on the

similarity attraction hypothesis (SAH) – which hypothesizes that people are attracted to other people with

similar physical or personal characteristics (Moreno and Flowerday, 2006, p. 43). They considered many

questions pertaining to the gender model that holds that boys learn better from male teachers and girls

learned better from female teachers. Their findings indicated that while the gender identity of the teacher

has some significant consequences, the impact on students does not quite fit the above model. Boys in

particular get along well with both male and female teachers, and both boys and girls expressed a

preference for teachers with high levels of professionalism, rather than a specific gender, when it came

academic pedagogy – in other words, their studies. However, in terms of emotional and personal

development, the gender of the teacher has an effect. The authors argued that the theory of attraction

(SAH) could not adequately explain the relationship between teacher gender and education. Their

findings suggest that a gender-invariant model should be applied to understand academic motivation

factors and the development of gender stereotypes.

7.2.Studies on the impact of field dependence-independence on the nature and success of pedagogical communication

The research of Drs. J. Packer and J.D. Bain (1978) and the more recent work by Kazakhstani

psychologists J.B. Akhmetova, A.M. Kim, A.T. Sadykova, and Delwyn L. Harnisch (2014) and D.G.

Naurzalina (2014) is relevant to the impact of being field dependent/independent on the nature and

success of pedagogical communication. They found that field dependent teachers tend to establish

informal relationships with their students and go beyond typical communicative roles, e.g. by holding

discussion sessions. In contrast, field independent teachers keep distance between themselves and their

students, preferring lectures as their primary form of interaction. Field dependent teachers are more

lenient in their assessment of pupils while field independent teachers put greater demands on their

students.

According to Jin Yan (2010), field dependence and field independence form parameters for

characterizing cognitive styles of approach. Thus, field dependent teachers are considered to exhibit low

differentiation and take significant advantage of psychological support, because of their well-developed

communication skills. Field independent teachers are the exact opposite: they rely on their developed

intellects and are prone to self-sufficiency while establishing distance from others.

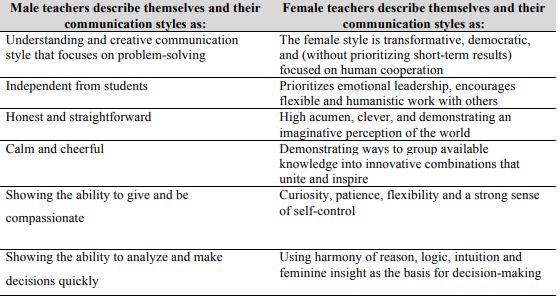

A survey to measure the self-reported teaching styles of male and female teachers conducted by

S.V. Rozhkova (2006) elaborated on Dr. Yan’s conclusions. Rozhkova’s findings are presented in table

Curiosity, patience, flexibility and a strong sense of self-control

Using harmony of reason, logic, intuition and feminine insight as the basis for decision-making

Dr. Rozhokova’s findings indicate that among high school teachers, there are significant

differences in how male and female teachers present themselves as professionals to students, and in what

professional and personal qualities are most valued by teachers of each gender in developing pedagogical

skills.

7.3. Gender Differences Manifested in Teacher Communication

Among teachers, males value communication styles that prioritize certain qualities such as

moderation, rationality, and common speech structures. Meanwhile, females value communication styles

that emphasize traits including diversity in sentence construction, emotional coloring, flexibility, and

general communicative skills.

E.N. Ilin (2003) cited the 1992 work of D.A. Mishutin, which found that male teachers are more

likely than female teachers to communicate in a lecture style to groups (66.3% vs. 62%), while female

teachers are more likely to use interpersonal communication one-on-one with students (38.0% vs. 33.7%).

Men are more likely than women to use non-verbal means of communication, and the converse holds true

as well. Dialogues and monologues are used equally often, and there are more female teachers than male

teachers on the whole (Ilin, 2003).

Research by Baylor and Kim (2004) on the impact of teacher ability on students conduct showed

that half of teachers' abilities to maintain rules in the classroom could be attributed to their own behavior

in class.

Another study, conducted by Mary A. Ochola and Dennis Juma (2014), examined how teacher

communication varied according to teacher gender and how that impacted students’ academic behavior in

secondary schools in Makadara, Nairobi. Their study demonstrated that the male and female teachers

exhibited clearly different teaching styles, and 65% of students indicated that they were aware that male

and female teachers taught differently. These findings support Tennina's theory of gender differences in

communication styles, which seeks to explain comprehension problems between men and women as

being due to very different cultures of communication exhibited by different genders.

Teachers often play a significant if unintentional role in encouraging academic gender stereotypes.

This has led to various disciplines in the sciences, particularly physics and computer science, becoming

stereotyped as belonging to men, while disciplines in the arts or humanities – including education – have

become increasingly dominated by women. The researchers noted that an acute shortage of same-gender

role models in various subjects for either genders meant that students had difficulty imagining themselves

in a role that they could imitate to master a discipline. However, while this has an impact on a macro

level, on an individual level, a lack of same-gender role models did not necessarily elicit student

dissatisfaction. Students in Nairobi, for example, claimed to want to be in classrooms where the teacher

was of the opposite sex.

Female teachers are generally aware of their particular potential to model progressive gender roles

as professionals. According to research by N.N. Ozhigova (2000), a plurality of female teachers (37%)

prioritize addressing gender roles in their classes, while other foci include the impact of speaking roles

(29%), representative roles (23%), and teaching roles in general (11%). These efforts give relevance to

the importance of considering gender gaps in particular disciplines and how male-dominated or female-

dominated majors and professions might be balanced.

The Bulgarian psychologists S. Ivanov and M. Ivanov (1991) studied the careers of physical

education teachers and came to the conclusion that female teachers of male students ask questions the

most often, and try as much as possible to explain and illustrate new material on which their students will

mostly be assessed. Male teachers encourage teamwork and organized training activities (Ivanov and

Ivanov, 1991). E.N. Ilin (2003) again cited the 1992 work of D.A. Mushutin that found that female

teachers prefer interpersonal and verbal communication, while men prefer group and non-verbal

communication. However, these studies are fragmented and of limited use to the emergence of a holistic

approach to pedagogical culture that would take into account the gender patterns of its formation and how

leading psychological features implicate the presence of numerous other qualities.

With increasing experience of pedagogical activity, professional stereotyping grows (Mynbayeva

A., Anarbek N., 2012). Awareness of gender differences in professional activity and communication

helps the teacher to monitor the development of professional deformations and regulate his/her

professional activity (Akhmetova Gulnas, 2015). At the same time, in order to overcome gender

imbalance in Kazakhstan schools it is preferable to create conditions to attract male teachers to the school.

7.4. Gender-labeling in School Systems

Gender dimensions are exhibited in the school system itself, such as in the "masculine" nature of

the content of education and in "feminine" forms of organization that require diligence and perseverance.

58

I.A. Kirillova (2005) built a three-dimensional model of a more distant teaching style that she

characterized as male. According to her research, the male teaching style is characterized by the use of

instructional techniques. It is based on a foundation of either reference notes or training, and prioritizes

research papers. It can also stress openness, either creatively, in problem solving, or through fact-

checking/editing. In relation to authors and reading, it asks students to analyze texts from the point of

view of the characters.

The female teaching style is characterized by specific methodological techniques including

staging, dialogues, performances, interviews, and heuristic forms of training. For example, active

dialogues in classrooms cede control to students in hopes of mutual efforts to work and gain knowledge,

often facilitated by creative teaching methods or activities.

A mixed teaching style is characterized by variety, activity organization, and the use of both male

and female instructional techniques, for example, holding a seminar that encourages group activity.

Mixed teaching styles present students with more holistic types of gender identity that manifest

themselves in the ability to form models of behavior that are loyal to student personalities and take

varying social norms into account.

8.Findings

8.1.Results

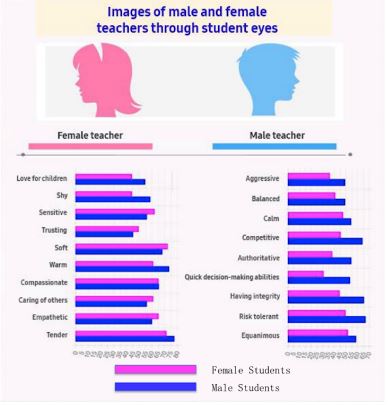

Following the example of S.V. Rozhkova (2006), the author conducted a similar survey that

revealed typical images of male and female teachers in the eyes of students of both sexes.

The survey was conducted among 80 students of School-Lyceum 1 Almaty. Respondents included

thirty-four male and forty-six female students from grades 5, 9, and 10. Survey questions were based on

the Bem Sex-Role Inventory (BSRI) questionnaire, a tool designed by S.L Bem (1974) to measure gender

perceptions.

The purpose of the survey was to identify the character traits that male and female students

identified in their male and female teachers. We also identified several problems, the solutions to which

will depend on a thorough analysis of the differing reported views.

-Students identified the extent to which teachers of different genders manifested

professionally significant traits.

Students identified basic traits applying to male and female teachers, respectively.

In an infographic, the described typical traits of male and female teachers are reported.

According to the survey responses, students viewed the following traits as being predominantly

manifested by female teachers: tenderness (70.8% of female students and 77% of male students,

respectively), empathetic (64.5% and 59.4% respectively), caring of others (60.4% and 55.4%

respectively), compassionate (64.5% and 64.8% respectively), warm (60.4% and 72.9% respectively),

soft (71.8% and 67.5% respectively), trusting (48.9% and 44.5% respectively), sensitive (61.4% and

55.4% respectively), shy (43.7% and 58.1% respectively) and having a love for children (43.7% and 54%

respectively).

The surveyed students saw the traits manifested by male teachers quite differently. Students

characterized their male teachers as possessing the following traits: equitable (51% of female students and

58% of male students, respectively), risk tolerant (48.9% and 66.2% respectively), strong (43% and

70.2% respectively), having integrity (43.7% and 64.8% respectively), having quick decision-making

abilities (30.2% and 52.7% respectively), authoritative (37.5% and 54% respectively), competitive

(44.7% and 63.5% respectively), calm (46.8% and 51.3% respectively), balanced (40% and 48.6%

respectively), and aggressive (35.4% and 48.6%).

The infographic below reports the data taken from the survey of students (Figure

The students’ responses reveal that male and female teachers present themselves in very different

ways. These differences are significant enough to be realized as setting gender norms in various

disciplines and professional activities in education.

A solution to problems created by these artificial norms is to have teachers adopt a gender-

conscious approach to pedagogical communication. A gender-conscious approach seeks to create

conditions for self-realization, individual expression, and the development of productive subjectivity in

the education process. A gender-conscious approach contributes to solving problems created by

idiosyncrasies in individual approaches to teaching by creating favorable conditions for the

comprehensive development of the teacher's personality, as well as increased opportunities for self-

realization and self-actualization on the part of the teacher.

8.2. Discussion

8.2.1 Gender-communicative competence

Through a systematic analysis of concepts and studies related to gender difference, the authors can

put forward a proposal to form gender-communicative competence among teachers as part of their

ongoing improvement of their professional skills. Structures and content of a model for gender-

communicative competence include:

1) An axiological component – an educator who demonstrates awareness will adopt the principles

of gender mainstreaming in education as a factor related to the psycho-physiological health of students, as

well as to the teacher's ability to take personal responsibility for the development of their pupils,

regardless of gender.

2) A cognitive component – a system of knowledge incorporating gender mainstreaming

categories in education, the hypothesis of attraction, and field-dependence and field independence among

teachers, manifesting natural communicative successes that take into account theories of gender

stereotypes and gender differences in the perception of male and female teachers.

3) A technological component – educators should have access to technology that is dedicated to

evaluating the process of gender mainstreaming and demonstrating the ability to use knowledge of gender

differences in pedagogical communication, to conflict situations, and to promoting adaptability to new

styles of pedagogy and communication patterns.

Situational modeling of gender equality must happen in dialogue, to aid in responses to

discrimination on the grounds of sex or gender as part of the necessary development of gender sensitivity.

A teacher’s level of gender-communicative competence, as evaluated on a scale of low – average –

above average – high, must be measurable according to developed, reasonable, and broadly applicable

standards.

Gender differences must be taken into account to form a productive training program for fostering

gender-communicative competence and improving pedagogical dialogue styles

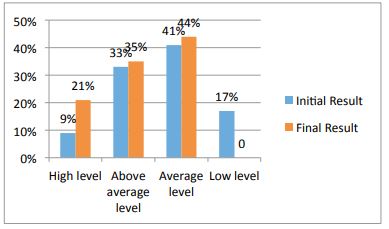

8.2.2 Practical experimental pedagogical research

This part of the study involved 45 teachers, divided into two groups with pre-entrance diagnosis

carried out, allowing the author to divide them into two nearly equal groups (23 women and 22 men,

respectively).

During the training program, visible changes were observed. Teachers skeptical about the impact

of gender differences on pedagogical information were nevertheless open to courses about pedagogy

serving as useful in-service training.

As a part of the training program, teachers were assigned a variety of exercises and provided with

many tools for remembering cases and vocabulary. The program took approximately 10 hours to

complete.

Observed changes in the results of the research and education groups (Figure

The proportion of teachers who possessed a high level style of pedagogical communication rose

from 9% to 21%. With this precedent, it is reasonable to propose that an acceptable average of 35% of

teachers is attainable, and a preferred average of 44% also possible.

While international research points to gender having a significant impact on pedagogical style and

effectiveness, teachers of both genders trained in gender-sensitive communication can be effective and

inspiring teachers for students of both genders. Survey results showed that Kazakhstani teachers

responded well to training in gender-communicative competence.

9.Conclusion

This study systematically conceptualized gender differences in communication styles to make a

model of gender-communicative competence that included axiological, cognitive and technological

components. A 10-hour program was developed to improve the style of teachers' pedagogical dialogue

through the formation of gender-communicative competence. The program was tested with compulsory

schoolteachers working in Almaty. Forty-five teachers attended the experimental session

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Levi for assisting with translation.

References

- Akhmetova, J. B.Kim A, M.Sadykova A, T. (2014). Using mixed methods to.

- (), study emotional intelligence and teaching competencies in higher education. Al-Farabi KazNU

- (), Bulletin: Psychology and Sociology Series. #2(49): 111-115.

- Akhmetova , G.Mynbayeva A& Mukasheva , A. (2015). Stereotypes in the Professional Activity of.

- (), Teachers. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. V. 171, 16 Jan 2015, 771-775.

- Amy L& Yanghee , Kim. (2004). Pedagogical agent design: The impact of agent realism, gender.

- (), ethnicity, and instructional role. Intelligent Tutoring Systems. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical

- (), Psychology, 42, 155-162.

- Bem, S. L. (1981). Bem Sex Role Inventory: Professional Alto, CA: Consulting. , manual. Palo

- (), Psychologists Press.

- Ilin, E. N. (2003). Differential psychophysiology in men and, Peter. , women. Sankt-Peterburg

- Ivanov, S.vanov , M. (1991). Psychology of the professional pedagogical communication in sport.

- (), education.” Sofia: NSA-PRES.

- Kirillova, I. A. (2005). Formation of gender identity among senior pupils through material on philological.

- (), disciplines in comprehensive schools. Doctoral Dissertation in Pedagogical Sciences. Volgograd.

- Moreno, Roxana. (2006). Students’ choice of animated pedagogical agents in.

- (), science learning: A test of the similarity-attraction hypothesis on gender and ethnicity.

- (), Contemporary Educational Psychology, 31.2: P.186-207.

- (), Mynbayeva A., Anarbek N. & Akhmetova G. Diagnosis of Pedagogical Professional Deformations: a

- (), View from Kazakhstan. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. V.69, 24 December 2012,

- (), 1289-1294.

- Naurzalina, D. G. (2014). Cross-cultural analysis of cognitive city maps belonging to residents of Almaty.

- (), and London. Al-Farabi KazNU Bulletin: Psychology and Sociology Series, #2. Almaty, Al-Farabi

- (), KazNU, P. 26-37.

- Ozhigova, N. N. (2000). Sensitive interpretations of self-actualization among professors (on material for.

- (), the teaching profession). Doctoral Dissertation in the Psychological Sciences. Krasnodar.

- Ochola, M. A. (2014). Role of gender communication on students’ academic behaviour.

- (), Survey of public secondary schools in Makadara Sub-county Nairobi. International Journal of

- Social Sciences and Entrepreneurship 1.13, (2014). 366-385.

- Packer , J.JD, Bain. (1978). Cognitive style and teacher-student compatibility. Journal of Education

- (), Psychology, 70: P.864-871.

- Rozhkova, S. V. (2006). Gender features in teacher pedagogical cultures. Dissertation in Pedagogical

- (), Sciences. Rostov.

- Usupova, Aidana. (2012). In the Senate, favor for increasing the number of male teachers in schools.

- (), Tengri News. Last modified on December 6, 2012. https://tengrinews.kz/kazakhstan_news/senate-

- (), vyistupili-uvelichenie-kolichestva-pedagogov-mujchin-224728/

- Jin , H. (2010). Cognitive styles affect choice response time and accuracy. Personality and Individual

- (), Differences: P.747-751.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

27 January 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-019-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

20

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-283

Subjects

Child psychology, developmental psychology, occupational psychology, industrial psychology, ethical issues

Cite this article as:

Akhmetova, G., Seitova, D., & Mynbayeva, A. (2017). Gender Differences In Teachers Pedagogical Communication Styles . In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences - icCSBs 2017, January, vol 20. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 54-63). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.01.02.7