Abstract

Due to the lack of assurance of adolescents from complete families with social risk of their parents' love for them, there is a discord of family relationships. Specially organized sports activity and measures of intervention for complete families with social risk promote mutual understanding and the improvement of relationships between adolescents and parents. We studied the views of adolescents from complete families with social risk on the relationships with the father and mother. A specially tailored intervention program promotes the improvement of the relationships between the adolescents and their parents. A version of the inventory “Children’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory” by Wasserman, Gorkovaya and Romitsyna (

Keywords: AdolescentInterventionSocial risk familiesSports

Introduction

A family experiencing various periods of life can either promote a child’s development or have a

destructive influence on the development of their personality. According to OECD (2011) data, today

there are many incomplete families in the world; parents marry more than once or cohabitate with casual

partners. In the period of global crisis, parents often lose their jobs and become long-term unemployed.

After a long time without a constant sufficient income, the family becomes a low-income family, receives

social housing and thus falls into the social risk group. A family obtains a special form of being with an

adolescent. Therefore the following question becomes important: what is the nature of relationships

between parents and children in social risk families?

The psychological climate in the family, the empathic ability of parents, communication and forms

of interaction of family members acquire a different nature, i.e. the adolescents interpret the role of the

family and their place in the system of relationships, subject the behavior of relatives to a more critical

judgment, give priority to interpersonal relationships (Dunn, 1988; Lerner & Steinberg, 2004).

At the age of adolescence, the social context changes – children have a tendency to spend less time

with family members. Especially when not feeling love from their parents, they try to win a good attitude

of their peers, having a significantly better mood from communication with friends (Larson & Richards,

1991). It is also known that unfavorable relationships in the family create social anxiety and lack of self-

confidence in children (Blote, Duvekot, Schalk, Tuinenburg, & Westenberg, 2010) because of the chance

of rejection by socially more well-off peers in a new situation of social interaction (Blote, Bokhors,

Miers, & Westenberg, 2012; Erath, Flanagan, & Bierman, 2007).

In social risk families, financial trouble can create and transform problems in relationships

between adolescents and parents. Children often externalize these problems onto their behavior (Ponnet,

Van Leeuwen, Wouters, & Mortelmans, 2015), which can lead to discord in relationships with others and

to symptoms of depression (Ehrlich, Cassidy, Lejuez, & Daughters, 2014). Parental stress due to unstable

and low family income and related insufficient care of the children can also increase the risk of cruel

behavior towards the child (Berger, 2004; Ha, Collins, & Martino, 2015; Sidebotham & Heron, 2006).

Nasr, Sivarajasingam, Jones and Shepherd (2010) note that adolescent girls are subjected to especially

high risk of gaining trauma related to violence due to material deprivation.

In school adolescents often fall into a “social risk” group because their relationship problems with

parents influence their learning success and social emotional behavior (Bradly, Corwyn, Burchinal,

McAdoo, & Coll, 2001; Hurellmann, 1990). Grigoryeva and Shamionov (2014) single out emotional

well-being as a stable predictor of academic success of elementary school children – the more positive the

parents’ assessment of the children’s adaptive behavior in school, the better the child feels emotionally.

Even with the presence of learning motivation but with the lack of warm relationships with teachers

(Jungert, Piroddi, & Thornberg, 2016), the lack of parental support and rejection from more successful

classmates creates a feeling of dissatisfaction with oneself and low self-esteem, which can consequently

lead to a bullying-victim status or a reactive-victim status (Cook, Williams, Guerra, Kim, & Sadek, 2010).

Therefore, to form a full understanding of relationships with others, adolescents from complete

families with social risk need psychological support. Supporting an adolescent means believing in their

abilities, seeing their positive traits, encouraging them verbally and non-verbally, and having confidence

in their success. First of all, psychological support from parents improves family relationships and

promotes pro-social behavior of adolescents (Houltberg, Morris, Cui, Henry, & Criss, 2016). With a lack

of adequate support, a child of any age experiences disappointment – from early childhood, development

of mental deprivation is promoted with a tendency to asocial behavior later (Laugmeier & Matejcek,

1984).

Unfortunately, parents in the process of interaction with adolescents do not differentiate between

such concepts as support, praise and reward. Unreasonable demands of adults have a negative impact on

the mood of an adolescent (Tseluiko, 2004). The first reaction of parents to a child’s failure is often

focusing on mistakes, whereas no attention is given to positive actions and reward. Praise is received for

strictly fulfilled demands or requests, but support is given in the form of help in completing a specific

task or with minimal progress in achieving something. Parents do not realize that support has an

enormous importance to adolescents during various types of failures (Levi, 2006).

Unfortunately, many adolescents do not receive timely support and suffer from failures, which is

why relationships with parents do not develop the feeling of confidence in children, a desire to achieve

success and the feeling of own importance. Constant focus on failure leads to lower self-esteem and

decreases the chance of success of the adolescents later in life (Obukhova, 1998). Success creates the

desire to achieve something more and increases self-confidence of adolescents (Maksimov, 2016).

Psychological help improves moral balance in the relationships of parents and adolescents in

families with social risk (Sinyagina, 2003). Thus, one of the ways to help adolescents from families with

social risk can be intervention that promotes awareness of a relationship problem with parents.

Problem Statement

Many families have a relationship dissonance, which can be explained by adolescents’ perceived

lack of assurance of parental love. In the study, we focus on adolescent girls from complete families that

fall into a social risk category where one of the parents has been unemployed for a significant period of

time.

Research Questions

Do organized sports activities and intervention for behavior adjustment foster mutual

understanding and improvement of relationships between adolescents and their parents?

Purpose of the Study

To examine how tailored programs of sports activities and intervention help improve relationships

between adolescent girls and their parents.

Research Methods

Participants

The participants of the study are 25 adolescent girls aged 13-15 representing 25 complete families

of an economically poorly developed south-east region of Latvia. Each adolescent has biological parents

and is the only child in the family. One of the parents has been unemployed for more than a year and is

not receiving unemployment benefits. Because the income level per person qualifies the family for a low

socioeconomic status, such families are considered “social risk families”. The families for participation in

the study were suggested by social care services. Participation of all family members was voluntary.

Methods

To study the views of adolescent girls on their relationships with the father and mother, the

inventory “Children’s Report of Parental Behavior” was applied (Wasserman, Gorkovaya, & Romitsyna,

2004). The inventory consists of 50 statements, grouped into 5 scales: POS – Positive interest of parents

towards adolescents; DIR – Authoritarian attitude; HOS – Hostile attitude; AUT – Autonomous and

independent attitude; NED – Inconsistent or wavering attitude.

The respondents filled in a separate form about each parent, giving each statement an assessment

on a three-point scale: 2 points – the statement fully describes the parenting principles of their mother or

father; 1 point – the statement partially describes the attitude of their mother or father; 0 points – the

statement is not relevant to their mother or father.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient α= .812 for the “Children’s Report of Parental Behavior” reflects the

reliability of the results, and the inventory can be used as a valid instrument in Latvian studies in the field

of education.

Procedure

The study was conducted in three stages. At the first stage the character of the adolescents’ views

on their parents’ attitude to them was determined. At the second stage, intervention was performed to try

and change the views and understanding of the parent’s attitude to the adolescents. The main objective of

the intervention was to form a positive attitude to oneself and others and develop cooperation in the

family. Apart from counseling and individual work, a sports festival and a sports party was organized.

The sports festival had a competitive nature, whereas the sports party involved games without winners or

losers. At the third stage the validity of the change and understanding of the adolescents’ views on their

relationships with parents was studied.

Findings

First Stage

According to the research plan, diagnostic work was performed to determine the nature of the

relationships of the adolescent girls and their parents. It is necessary to study the views of the children on

the attitude of both parents to them – the father and mother. Statistical analysis of the obtained data was

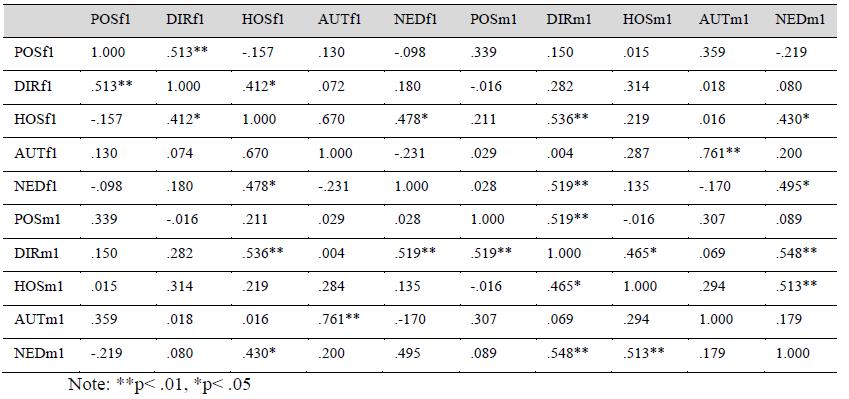

performed. For convenience, the results obtained are presented in Table 1.

As seen from Table 1, a positive significant correlation of the adolescents’ views on their parents’

attitudes to them was found at level p< .01 on the following scales:

§ Hostile attitude of the father (HOSf1) and authoritarian attitude of the mother (DIRm1);

§ Autonomous attitude of the father (AUTf1) and autonomous attitude of the mother

(AUTm1);

§ Inconsistent attitude of the father (NEDf1) and authoritarian attitude of the mother (DIRm1).

Positive significant correlation at level p< .05 exists between the adolescents’ views on their

father’s and mother’s attitude to them on the Hostility scale of the father (HOSf1) and inconsistent

attitude of the mother (NEDm1).

Having analyzed the results, it can be stated that in general adolescent girls describe their mother’s

attitude to them as authoritarian and demonstrative. When an adolescent believes that one of the parents is

hostile to them, then they believe that the other parent has an inconsistent or authoritarian and

demonstrative attitude to them. It can be assumed that, according to the adolescents, autonomous and

independent attitude of one of the parents means less control and more independence from the other

parent. However, inconsistent attitude of the father provokes authoritarian attitude of the mother.

Second Stage

Intervention Program

In order to improve the family relationships, we organized psychotechnical games with

adolescents in groups; interventional and sports activities with adolescents and their parents, and

counseling for parents.

During counseling meetings with parents, their behavioral strategy with children was developed.

Recommendations were given on the improvement of their relationships:

§ Accept the adolescent the way she is: only behavior can upset you, but not the child; discuss

their actions but not the child.

§ Praise the adolescent more often and tell her that she is loved unconditionally.

§ Help the adolescent see her strengths and understand herself.

§ Accept the adolescent’s weaknesses; teach her to solve her problems calmly a step at a time.

§ Be calm about the changing interests of the adolescents.

§ Control your own statements and emotional assessment of the adolescent’s behavior.

The following guidelines for intervention in groups were used:

§ Individual approach to each adolescent;

§ Play and counseling form of work with adolescents to maintain their interest in the activities;

§ Kindness in relationships with the adolescents; blame for unsuccessful performance is

unacceptable;

§ Support using positive emotional assessment of any achievement of the adolescent so that

success is experienced as happiness;

§ Development of the adolescents’ need for independent work and the ability to adequately

assess their relationships with parents.

We have developed and conducted a complex of psychotechnical games promoting the formation

of positive emotional experiences and views on relationships with parents in adolescents from complete

families with social risk.

Individual approach was applied in the intervention group, i.e. we made no attempt to teach the

adolescents anything against their will in order to maintain their motivation for participation in the

activities (Guseva, Dombrovskis, & Murasovs, 2011). We believe that the need of an adolescent to

understand and positively interact with parents can only be formed if her individual activity is developed.

Psychotechnical games were aimed at developing the communicative competence, self-confidence

and self-knowledge skills – we used exercises directed at self-disclosure, interpersonal confrontation and

at expression of strong emotions, and at formation of positive views on their parents’ attitude to them.

Game tasks were also used that were necessary as a means of maintaining the adolescents’ interest

towards the classes. The duration of the program was 15 classes, 45 minutes long, once per week. The

group was divided into two subgroups – 12 and 13 people.

To develop the need of the adolescents to understand and to develop a positive attitude to

themselves and others, situations were created during the activities that were aimed not at routine task

performance but at encouraging personal activity. It was not acceptable to ask an unexpected question and

demand an immediate answer. The adolescents were given enough time to think and prepare an answer.

Such remarks as “good” and “well done” formed confidence in their abilities; the adolescents were

praised for persistence and effort, even if the result was far from what was desired.

Competitive intellectual tasks were an obligatory component of the activities which allowed

bringing out the adolescent’s desire to be successful. At the beginning of work with adolescents, we used

games and exercises that were engaging and did not pose particular difficulty. This was done so that the

adolescents could feel the joy of winning; therefore such activities were conducted with positive

emotional background. When tasks became more difficult, the adolescents had to solve difficult problem

situations. Therefore it is extremely important to stress that at this stage it is unacceptable that the

adolescents lose interest in the activities. Because the group work was also aimed at psychological

support of each child, feedback from parents was important. Feedback was discussed at counseling

meetings with parents – psychological help needed to be provided at home after classes, discussing what

was happening in the group. Therefore, success depended on the extent to which the adults believed in the

abilities of their child.

Sports Festival “Sports and Us”

After conducting 10 classes for the adolescents and their parents, a sports festival called “Sports

and Us” was organized. Special emphasis was put on the fact that the whole family must participate in the

sports competitions and that common result depends on each participant. The main aim of the sports

festival was developing cooperation and interaction among all family members. Concurrent aims we were

trying to reach were: popularization of healthy lifestyle, meaningful spending of leisure time,

participation of the whole family in preserving their physical and mental health, and promoting the

development of the adults’ and adolescents’ interest towards active lifestyle.

During the festival, positive emotions, good mood and friendly communication were dominating

in the gym. Sports competitions taught both adolescents and their parents social solidarity and tolerance,

broke stereotypes and changed attitudes in the family and to other members of society, and improved

cooperation skills.

Sports festival consisted of three competitions:

1) „First Competition”. Fathers were the first to participate in the competition (running on a

gymnastic bench, dribbling a basketball); then mothers joined the competition (running while repeatedly

hitting a balloon upward using a badminton racquet; the decisive match was played by their children

(running on hands and knees while pushing a ball with their head).

2) „Second Competition”. Only parents participated in this competition; it promoted the skills of

coordinating one’s actions (running when the right leg of the father is tied to the left leg of the mother).

3) „Third Competition”. In this competition, all family members participated again (the parents

had to carry their child on crossed arms a certain distance and bring her back). The whole team also had

to reach the finish line while playing volleyball with balloons without letting them reach the ground.

Each team had a captain and a name.

After the competitions, all teams received prizes for successful completion of all the competition

stages to the applause of spectators.

6.2.3. Sports Party “The New Games or Games without Winners or Losers”

After the end of the interventional group activities with adolescents, a sports party was organized

called “The New Games or Games without Winners or Losers”.

In the last decade “the new games” have been popular around the world. The main principle of the

games is that there are no winners or losers. The games are based on the idea of cooperation among

participants instead of competition: mutual aid in achieving the goal. All participants gain satisfaction

from the activity because no participant can be excluded from the game until its end. “The new games”

are for people of any age, gender, physical state and level of training. Each participant believes in the help

of other participants and has no doubt about their own safety. During the game anyone can take initiative,

change the nature of the game and be a leader (LeFevre, 2002; Oatman, 2007; Orlick, 2006).

The sports games organized at the sports party correspond to the model of Spartian Games –

“SpArt”: “Spirituality”, “Sport”, and “Art”. This humanism-oriented sports model integrated with art was

developed by Stolyarov (2003).

The following are examples of “the new games” that were played during the sports party:

• “Musical chairs” is a game where the players sit on chairs arranged in a circle. When music

starts playing, the players get up and start moving from chair to chair while one of the chairs

is removed from the circle. When the music stops playing, each player has to sit on a chair or

on the lap of another player. The game continues until all players are sitting on one chair

(Tczen & Pahomov, 1999).

• “Rolling a ball in a circle”. The players are sitting on the floor making a tight circle. The

ball is positioned in the lap of one of the players. The task is to move the ball in circle from

one lap to another without using your hands. Each participant can change the direction of

the ball if they want to. A verbal signal can be given about the change of direction (“stop”,

“to the left”, “to the right”, etc.) (Tczen & Pahomov, 1999).

Findings of the Third Stage

At the third stage of the study, the diagnostic procedure to determine the views of the adolescents

on their parents’ attitude to them was repeated. Results were compared before and after the interventional

activities. A dynamics in the views of adolescents from complete families with high social risk on

positive attitude of their parents to them was found. For convenience, the results of statistical processing

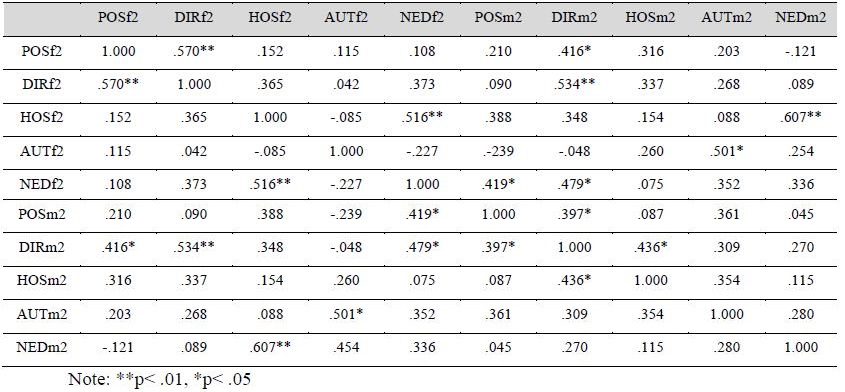

obtained after the interventional activities are presented in Table 2.

A positive significant correlation of the views of adolescent girls’ from complete families on their

parents’ attitude to them is found at the level of p< .05 on the following scales:

§ If the adolescent feels a positive attitude of their father (POSf2), but an authoritarian attitude

from the mother (DIRm2);

§ If the adolescent feels an autonomous attitude of both parents (AUTf2 – AUTm2);

§ If the adolescent feels a positive attitude of their mother (POSm2), but an inconsistent

attitude of their father (NEDf2);

A positive significant correlation at the level p< .01 exists between the views of the adolescents

from complete families with high social risk on their mother’s and father’s attitude to them on the

following scales:

If, according to the adolescents, both parents have an authoritarian attitude to them (DIRf2-

DIRm2);

If the adolescent feels a hostile attitude of their father (HOSf2) and an inconsistent attitude of

their mother (NEDm2).

After studying the views of adolescent girls on their relationship with the mother and father and

summarizing the results obtained after a comparison of data of the first and third stage of the study, it

must be noted that the view of 20% of respondents on their father’s attitude to them became more

positive; 44% of adolescents believe that their father’s attitude to them became less authoritarian. Hostile

attitude of the father to the adolescents, according to the children, has changed to positive for 24% of

respondents. The view of authoritarian attitude of the father has been found for 20% of respondents and

28% of adolescents feel that their father’s attitude to them became more positive rather than inconsistent.

Overall, for 44% of adolescents, the view on the mother’s attitude to them has improved; 32% of

adolescents adequately perceive authoritarian attitude of the mother and consider it positive; 20% of

respondents believe that the hostile attitude of the mother has changed to positive. According to 16% of

respondents, their mother gives them freedom of action and trusts them. The view on inconsistent attitude

of the mother has changed for 40% of adolescents.

Conclusion

When entering adolescence, relationships with parents are very important to children, as well as

the relationship between their parents, which is a basis for stable relationships in the family. Development

of the adolescent’s awareness of their “Self” depends not only on different social contexts to which they

belong, but also on mutual input into the relationship between parents and children (Scabini & Cigoli,

2006). Moreover, parents of anxious and rejected children usually have a negative attitude regarding their

children (Laskey & Cartwright-Hatton, 2009).

Often parents, while having high expectations of their children, are unable to offer them a model

of career growth corresponding to the knowledge obtained. Often, the views of parents and adolescents on

further life prospect do not match, which leads to lack of mutual understanding and harmony in the

family. This is why it was important to perform intervention in social risk families in order to harmonize

internal relationships where, as a result, the adolescent has become the subject of interaction instead of

the object of influence.

In order to create an intervention program, analysis of existing difficulties in the relationships

between children and parents was performed; namely, during individual consultations, interindividual

causes were found, related to the peculiarities of family upbringing and macrosystemic causes, related to

socio-cultural peculiarities of life of the family.

The supportive role of the family as a system for development of a child’s personality is

mentioned by many researchers (Cox & Paley, 2003; Levi, 2006; Obukhova, 1998). Besides, boys and

girls have different emotional reactions to family conflicts – boys react to didactic disturbances, whereas

girls react to disengagement in family relationships in general (Lindahl, Bregman, & Malik, 2012). In the

context of sustainable education, for developing stability of future trusting relationships, apart from taking

into account gender differences, the focus is on the way parents consider the interests and needs of their

children at the beginning of school life (Drelinga, Ilisko, & Zarina, 2015). In this regard, Ryan and Deci

(2000) offer to consider three innate needs – competence, autonomy and relatedness, and satisfying each

can strengthen self-motivation, positively impact mental health and maintain well-being in the family.

The necessary economic income and relationship culture in the family must become a long term

strategy of family upbringing of adolescents (Hurellmann, 1990). Kwon, Janz, Letuchy, Burns and Levy

(2016) state that in families with low economic status, the role of the father is important in supporting the

adolescents’ participation in sports activities. This fact is especially important in our case because in the

most of cases, the fathers were the ones who were unemployed.

The results of our study demonstrate that voluntary participation of adolescent girls and their

parents from complete families with social risk in interventional activities together with sports activity

gives a positive result in the improvement of family relationships in a relatively short period of time.

Thus, stable relationships between adolescents and parents can be considered a predictor of further self-

improvement and family well-being.

References

- Berger, L.M. (2004). Income, Family Structure, and Child Maltreatment Risk. Children and Youth

- Services Review, 26(8), 725-748. doi: DOI: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.02.017

- Blote, A.W., Bokhorst, C.L., Miers, A.C., & Westenberg, P.M. (2012). Why are Socially Anxious Adolescents Rejected by Peers? The Role of Subject-group Similarity characteristics. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22, 123-134. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00768.x Blote, A.W., Duvekot, J., Schalk, R., Tuinenburg, E., & Westenberg, P.M. (2010). Nervousness and Performance Characteristics as Predictors of Peer Behavior Towards socially Anxious Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(12), 1498-1507. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9463-3

- Bradly, R.H., Corwyn, R.F., Burchinal, M., McAdoo, H.P., & Coll, C.G. (2001). The Home Environments of Children in the United States part II: Relations with Behavioral Development through Age Thirteen. Child Development, 72(6), 1868-1886. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00383 Cook, C.R., Williams, K.R., Guerra, N.G., Kim, T.E., & Sadek, S. (2010). Predictors of Bulling and Victimization in Childhood and Adolescence: A Meta-Analytic Investigation. School Psychology Quarterly, 25(2), 65-83. doi: 10.1037/a0020149 Cox, M.J., & Paley, B. (2003). Understanding Families as Systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 193-196. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.01259 Drelinga, E., Ilisko, D., & Zarina, S. (2015). The Text “Rita, Raitis and Number” by J.Mencis (Sen.) and D.Dravina for the Pre-school Learners [Ikimokyklinio ugdymo J. Mencio (Sen.) ir D. Draviņos matematikos vadovėlis „Rita, Raitis ir skaičiai“]. Pedagogika, 120(4), 169-179.

- doi: 10.15823/p.2015.046 Dunn, J. (1988). The Beginnings of Social Understanding. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Ehrlich, K. B., Cassidy, J., Lejuez, C. W., & Daughters, S. B. (2014). Discrepancies About Adolescent Relationships as a Function of Informant Attachment and Depressive Symptoms. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(4), 654–666. doi:10.1111/jora.12057 Erath, S.A., Flanagan, K.S., & Bierman, K.L. (2007). Social Anxiety and Peers Relations in Early Adolescence: Behavioral and Cognitive Factors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 405-416. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9099-2 Grigoryeva, M.V., & Shamionov, R.M. (2014). Predictors of Emotional Well-being and Academic Motivation in Junior Schoolchildren. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 146, 334-339.

- doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.08.106 Guseva, S., Dombrovskis, V., & Murasovs, V. (2011). Remedial Work as a Means of Developing Positive Learning Motivation of Adolescents. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 29, 43-52.

- Ha, Y., Collins, M.E., & Martino, D. (2015). Child Care Burden and the Risk of Child Maltreatment among Low-Income Working Families. Children and Youth Services Review, 59(C), 19-27. doi: DOI: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.10.008 Houltberg, B., Morris, A.S., Cui, L., Henry, C.S., & Criss, M.M. (2016). The Role of Youth Anger in Explaining Links Between Parenting and Early Adolescent Prosocial and Antisocial Behavior. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 36(3), 297-318. doi: 10.1177/0272431614562834 Hurellmann, K. (1990). Parents, Peers, Teachers and Others Significant Partners in Adolescence.

- International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 2(3), 211-236. doi: DOI: 10.1080/02673843.1990.9747679 Jungert, T., Piroddi, B., & Thornberg, R. (2016). Early Adolescents’ Motivations to Defend Victims in School Bulling and Their Perceptions of Student-Teacher Relationships: A Self-Determination Theory Approach. Journal of Adolescence, 53, 75-90. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.09.001 Kwon, S., Janz, K.F., Letuchy, E.M., Burns, T.L., & Levy, S.M. (2016). Parental Characteristic Patterns Associated with Maintaining Healthy Physical Activity Behavior during Childhood and Adolescence. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 13(1), 58. doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0383-9 Larson, R., & Richards, M.H. (1991). Daily Companionship in Late Childhood and Early Adolescence: Changing Developmental Context. Child Development, 62(2), 284-300. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01531.x Laskey, B. J., & Cartwright-Hatton, S. (2009). Parental Discipline Behaviours and Beliefs about Their Child: Associations with Child Internalizing and Mediation Relationships. Child Care Health and Development, 35(5), 717–727.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00977.x Laugmeier, J., & Matejcek, Z. (1984). Psikhicheskaya deprivacija v detskom vozraste (Psychic Deprivation in Childhood). Prague: Avicenum. (in Russian).

- LeFevre, D. N. (2002). Best New Games. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Lerner, R.M., & Steinberg, L. (2004). Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. New York: John Wiley.

- Levi, V.L. (2006). Kak Vospityvat’ Roditelei ili Noviy Nestandartniy Rebyonok (The Nonstandard Baby,

- or how to Educate Parents). Moscow: Toroban. (in Russian).

- Lindahl, K.M., Bregman, H.R., & Malik, N.M. (2012). Family Boundary Structures and Child Adjustment: The Indirect Role of Emotional Reactivity. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(6), 839-847. doi:10.1037/a0030444 Maksimov, A.M. (2016). Kak Ne Stat’ Vragom Svoyemu Rebyonku (How not to become the Enemy of your Child). Sankt-Petersburg: Piter. (in Russian).

- Nasr, I., Sivarajasingam, V., Jones, S., & Sheperd, G. (2010). Gender Inequality in the Risk of Violence: Material Deprivation is Linked to Higher Risk for Adolescent Girl. Emergency Medicine Journal, 27(11), 811-814. doi: 10.1136/emj.2008.068528 Oatman, D. (2007). Old favorites, new fun: physical education activities for children. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Obukhova, L.F. (1998). Detskaya Psychologiya: Theoriya, Phakti, Problemi (Developmental Psychology: Theory, Facts, Problems). Moscow: Trivola. (in Russian).

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development). (2011). Doing Better for Families.

- Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/doingbetterforfamilies.htm Orlick, T. (2006). Cooperative Games and Sports: Joyful Activities for Everyone. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Ponnet, K., Van Leeuwen, K., Wouters, E. & Mortelmans, D. (2015). A Family System Approach to Investigate Family-Based Pathways Between Financial Stress and Adolescent Problem Behavior.

- Journal of Research on Adolescence, 25(4), 765–780. doi: 10.1111/jora.12171 Ryan, R.M., & Deci, E.L. (2000). Self-determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066X.55.1.68 Scabini, E., & Cigoli, V. (2006). Family Identity: Ties, Symbols, and Transitions. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Sidebotham, P., & Heron, J. (2006). Child Maltreatment in the “Children of the Nineties”: A Cohort Neglect, 30(5), 497-522. Study of Risk Factors. Child Abuse and doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.11.005 Sinyagina, N.Y. (2003). Psychologo-pedagogicheskaya korrektsiya Detsko-roditel’skih Otnosheniy (Psychopedagogical Intervention in Children’s and Parents’ Relationships). Moscow: Vlados. (in Russian).

- Stolyarov, V.I. (2003). Innovatsionnaya Spartianskaya Tehnologiya Duhovnogo i Phizicheskogo Ozdorovleniya Detey i Molodezhi (Innovative Spartian Technology of Mental and Physical Health of Children and Adolescents). Moscow: Tsentr Razvitiya Spartianskoi Kul’turi. (in Russian).

- Tczen, N.V. & Pahomov, Y.V. (1999). Psychotrening: Igri i Uprazhneniya (Psychological Skills Training: Games and Exercises). Moscow: Nezavisimaya firma “Class”. (in Russian).

- Tseluiko, V.M. (2004). Vi i Vashi deti. Psychologiya Sem’yi (You and Your Children. Family Psychology). Rostov-upon-Don: Phenix. (in Russian).

- Wasserman, L.I., Gorkovaya, I.A., & Romitsyna, E.E. (2004). Roditeli Glazami Podrostka: psihologicheskaya diagnostika v mediko-pedagogicheskoi praktike (Parents in the Eyes of Teenager: Psychological Diagnostics in Medical Pedagogical Practice). Sankt-Petersburg: Rech. (in Russian).

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

27 January 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-019-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

20

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-283

Subjects

Child psychology, developmental psychology, occupational psychology, industrial psychology, ethical issues

Cite this article as:

Guseva, ., Dombrovskis, V., & Capulis, S. (2017). Intervention And Sports For Adolescent Girls From Complete Families With Social Risk. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences - icCSBs 2017, January, vol 20. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 185-196). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.01.02.19