Abstract

Non-attachment in Buddhism has been conceptually proposed to have an impact on personal well-being. Nevertheless, there has been limited empirical studies investigating how non-attachment influences health, and in particular, its effect on eudaimonic well-being. Our key research questions were: Do demographics influence non-attachment and psychological well-being? And, to what extent can nonattachment and demographics affect psychological well-being? To investigate these, developed the following aims: (1) to compare non-attachment and psychological well-being in people with different Buddhist status and types of practice (indicated by the types of groups they practiced with, the extent to which they took refuge in The Three Jewels, and the frequency with which they practiced the Dharma); (2) to examine the relationship between non-attachment in Buddhism and psychological well-being, including the related components of psychological well-being. Participants were 472 Buddhists from five sanghas in Vietnam. Data was collected from January to April, 2016. Each participant was given a battery of measures comprised of: The Non-Attachment Scale (

Keywords: Non-attachmentWell-beingPsychological Well-beingBuddhist

Introduction

Religious psychology is one of the oldest branch of psychological science (Joshi & Kumari, 2011).

It emerged from the early work of James (1902), Freud (1913), and Jung (1938), and has recently

experienced a rise in popularity (Pargament, Koenig, Tarakehwar, & Hahn, 2004). In the last ten years,

there has been increasing appreciation among psychologists and practitioners of the potential for religious

principles and philosophy to influence human well-being. Some argue that, for the reason that

participation in a particular religion can extend a person’s support network, religion promotes individual

well-being (Diener et al., 2011; Krause & Hayward, 2013; McIntosh, 1995; Revheim & Greenberg,

2007), others argue that it reduces distress (Hefti, 2011); enhances stress coping ability (Pargament et al.,

2004; Park, 2005; Bradshaw et al., 2010), promotes self-evaluation (Whittington & Scher, 2010),

purposeful perception of life (Martos et al., 2010; Diener et al., 2011), and postive perception of the

future (Levin, 2010).

In the last decade, psychologists have become interested in contructs and practices of Buddhism

and Buddhist psychology (Pargament et al., 2004; Ekman et al., 2005; Wallace & Shapiro, 2006). This

trend may be reflecting interest among many agnostic scientists in a “spiritual” practice that can be

beneficial for nonreligious people, however, it could also be owing to increased recognition of Buddhist

practices in clinical psychology, and from a recent movement towards a positively-orientated approach to

psychology and well-being (Snyder & Lopez, 2009).

According to Buddhism, attachment, adversion, and ignorance are the three major human poisons,

and they are innate to the human condition (Dalai Lama, 2000). However, they can be resisted and virtues

cultivated, through the practice of generosity, which should be performed in the spirit of unconditional

love (i.e., giving freely, without attachment or expectation) (Drakpa, Sunwar, & Choden, 2013). In other

words, the Buddhist approach to happiness is to strive to free one’s self from attachment.

Basic concepts

Attachment

Attachment theory was first proposed by Bowbly (1969, 1973) and Ainsworth (1985). It considers

that the quality of a person’s relationships and their mental states throughout their lifetime, are strongly

determined by the type of attachment they experienced with their primary caregiver during early

childhood. Although attachment theory focuses on the interaction between an individual’s relationships

and personality development, little consideration was given to how this model could be utilised to create

the conditions for psychological wellbeing in adulthood (Sahdra, 2013).

Buddhist psychology, meanwhile, describes attachment (

thinking’ – the mistaken decision to look for security and happiness in possessions, wealth, and reputation

(Sahdra, 2013). There are four parameters of attachment (

(

customs (

doctrines of self). The Dalai Lama (2001) suggests attachment as the origin and root of suffering and the

reification of the ego-self. In this study, we use Shonin and colleagues (2014) definition of attachment as

“the overallocation of cognitive and emotional resources toward a particular object, construct, or idea to

the extent that the object is assigned an attractive quality that is unrealistic and that exceeds its intrinsic

worth” (p. 126).

Non-attachment

Non-attachment (

craving for existence (Harris, 1997), or the absence of lust. Non-attachment, however, does not imply

withdrawal, but rather the freedom to see the world clearly. Non-attachment is achieved once a person is

aware that no possession, relationship or any achievement is infinite and that none will be able to satisfy

human need (Harris, 1997). In other words, non-attachment is the flexibility to free oneself from desire

and to choose peace. A person who practices non-attachment is not tied to any opinion, appearance or

desire for possession, and they may be more resilient to the trap of self-defensive cognitions (Sahdra et

al., 2010)

Well-being

Well-being is the subjective evaluation of general life satisfaction and can also refer to specific

life-domains. Well-being is considered from two different perspectives: hedonic well-being and

eudaimonic well-being.

From the hedonic perspective, well-being is life experience with the presence of satisfaction and

absence of sadness (subjective well-being) (Bradburn, 1969; Diener, 1984). According to Diener, Lucas

and Oishi (2005), subjective well-being is the individual evaluation of the cognitive and affective aspects

of their life. Two core principles of subjective well-being are cognition (satisfaction) and affect (both

positive and negative affect) (Bradburn, 1969; Andrews & Withey, 1976; Diener et al., 1985). Other

authors, however, have conceptualised subjective well-being as a combined model, between pleasure

(positive emotion) and engagement and meaning (Seligman et al., 2006). Alternatively, it has also been

conceived as a variable determined by excited activities balanced with challenges and personal skills

(Csikszentmihalyi, 1990).

In contrast, the Eudaimonic approach, does not separate human well-being from human potential.

Once the potential is actualized, a person will function healthily and positively (Diener, 1985; Ryan &

Deci, 2001). Being well does not only mean experiencing life with more excitement and less sadness, but

it is a process of self-actualization (Ryff, 1989). Ryff (1989) proposed a six-factor model of eudaimonic

well-being: positive self-perception (self-acceptance), positive relations, independence and autonomy, life

purpose, environmental mastery, and personal growth. The five dimensions model of Keyes (1998), on

the other hand, conceptualized well-being as being composed by: social integration, social contribution,

social acceptance, social actualization, and social coherence.

Contemporary researchers, while agreeing that well-being features a subjective, psychological, and

a social aspect (Negovan, 2010), have increasingly emphasized the psychological aspect of human

experience, and with it, its relation to religious belief. For example, Unterrainer and colleagues (2012)

suggest that from a religious approach, well-being has six dimensions: immanent hope, forgiveness, a

sense of meaning, transcendent hope, general religiosity, and connectedness. Returning to Buddhism, as

another example, Buddhism does not emphasize the achievement of goals or self-satisfaction, but on the

self-balance experience (Joshi & Kumari, 2011) and positive relaxation (Tsai et al., 2007). Well-being

from a Buddhist approach is a result of freedom from the mind itself, namely from its tendency to angst,

and the result of the ability to realise one's fullest potential in term of wisdom, compassion, and creativity

(Wallace & Shapiro, 2006).

Non-attachment and well-being

Distinct from other religions, Buddhism conceptualizes human life as suffering and from which

no Buddha or spiritual feature can help people to escape (Finn & Rubin, 2000). In Buddhism, suffering is

not simply one's dissatisfaction, it is the result of humanity’s misconception of life (Ekman et al., 2005).

Therefore, rather than emphasizing the image of Buddha as a saviour figure, Buddhism focuses on the

message of The Four Noble Truths as an approach to life. The first, the Truth of Suffering, and the fourth

truth, the Truth of the Path Leading us to the End of Suffering, convey an essential component of

Buddhism, that life begins and ends with suffering. The other two truths have closer relations with non-

attachment and with psychological well-being.

The Truth of the Cause of Suffering refers to the Buddhist concept that craving and ignorance are

the root causes all suffering. Craving is commonly presented under the form of

According to this model, sadness, is the result of the human craving for objects that they found attracted

to (Chah, 2011). In other words, humans have a tendency to find happiness in the possession of material,

pleasure, health, knowledge, position, compliment, and recognition. As a result, they are attached to their

environment and their relationships with it, rather than their inner strength for their own happiness.This

concept follows that, once attached, well-being is unstable according to the variation in the outside

phenomena (i.e., the possession of objects, relationships with others) that it is now dependent on. From

this perspective, status is another object of attachment, people become tied to the pressure of having to

achieve, and to possess in order to find happiness (Sahdra et al., 2010).

The Truth of the End of Suffering implies that only when all the deep roots of suffering are

removed, suffering will end. And with the end of suffering, happiness emerges as freedom from

expectation and dissatisfaction (Fink, 2013). According to Buddhism, as everything is impermanent,

happiness cannot be sustained by holding onto property or objects. Buddhism proposes that everything

has three characteristics: impermanence, selflessness, and dissatisfaction, and each existence is the

consequence and cause of another, nothing is absolute or unchangeable. Although Buddhism has been in

existence for a centuries and has spread around the globe, this perception is not common to humanity, and

often theworld is perceived as absolute and all forms as completely independent from each other (Ricard,

2006). Therefore, the majority of people seek happiness in the pursuit of success, youth, health,... Those

satisfactions are controlled by one's environmental stimuli, and their social interactions. Accordingly,

when those stimuli are removed, happiness is also diminished (Wallace & Shapiro, 2006).

From a Buddhist point of view, the only way to achieve inner peace is to eliminate attachment, or

to cultivate non-attachment. Non-attachment does not mean to run away or repress negative thoughts and

emotions, but to face and carefully analyse where they come from, how they take place, and how they

impact one's self and others. For example, when a new situation arises, one is often overcome with greed,

hatred, and ignorance, from which emotions arise. These emotions, which could be pleasant, unpleasant,

or neutral, act to blind humans to the true nature of peace, they will ignore, evade or deny it, and instead

cling to their attachment (Fryba, 1995). The focus of Buddhism, therefore, is to free people from their

emotion in order to perceive and accept things / phenomena as they are, not as they are created from the

illusions of the mind (Grabovac et al, 2011).

Problem Statement

Several empirical studies have indicated a positive association between non-attachment and well-

being. For example, empirical findings indicate that subjective well-being and constructive well-being are

negatively associated with destructive emotions (Wang et al., 2016), stress (Naidu & Pande, 1990), and

closed-mindedness (Sahdra & Shaver, 2013). However, from the hedonic approach, there has been little

research into the relationship between non-attachment and eudaimonic well-being. With this study we

hope to contribute to this gap in the literature.

Research Questions

As the above discussion highlights, the relationship between non-attachment and well-being has

been largely neglected in research. The present study is designed to fill this gap. Our research questions

are:

Q1. Is there an effect of demographics on non-attachment and psychological well-being? (gender,

age, refuge status (in The Three Jewels), practice Dharma, frequency of mindfulness practice and

mediation)

Q2. What is the association between non-attachment and psychological well-being?

Q3. What is the contribution of non-attachment and demographics to the variation of

psychological well-being?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this research is:

To compare non-attachment and psychological well-being in people with different Buddhist status

and types of practice (group of practice, taking refuge in The Three Jewels, and frequency of mindfulness

practice and meditation).

To examine the relationship between non-attachment in Buddhism and psychological well-being,

including related components of psychological well-being.

Research Methods

Participants

Participants were 472 Buddhists from Vietnam. More than 70% were female. 90.5% were

laypersons, and participants came from five different sanghas. 41.5% had taken refuge. Detailed

information on the demographics of participants is presented in Table

Measure

colleagues (2010) to measure the perception of non-attachment. This scale has 30 items, rated on a likert

scale from 1: Totally disagree to 6: Totally agree. NAS showed excellent reliability with Cronbach’s

Alpha of NAS: .93.

item-scale that covers six domains of psychological well-being, including: (1) self-acceptance (2) positive

relations with others, (3) autonomy, (4) environmental mastery, (5) purpose in life, and (6) personal

growth. The internal consistency (or) coefficients reported by Ryff (1989) for the scales were as follows:

self-acceptance, .93; positive relations with others, .91; autonomy, .86; environmental mastery, .90;

purpose in life, .90; and personal growth, .87.

There was evidence of good overall reliability with Cronbach's alpha .95. For each of the six

subscales, internal consistency exceeded .70: self-acceptance, 𝛼 = .76; positive relations with others: 𝛼 = .87; environmental mastery: 𝛼 = .86; purpose in life: 𝛼 = .84; personal growth 𝛼 = .86. However, it should be noted that the autonomy scale resulted in a Cronbach's alpha below .70 (𝛼 = .57).

Procedure

Data was collected at five Sanghas around Vietnam. In December 2015, a pilot study was

conducted with 53 Buddhists, two monks who have practiced the Dharma for over 20 years, two

laypersons, and with one Buddhist researcher to check the face validity of translated scales. Suggestions

were considered and translations adjusted to make the scales more accessible to Vietnamese Buddhists.

The survey was administered from February to May 2016 and from 500 invitations, 472 agreed to

participate, giving a response rate of 94.4%.

Data analysis

Data was coded and analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS).

Inspection of the Non-attachment Scale (Sahdra et al., 2010) and the Psychological Well-Being Scale

(Ryff, 1989) indicated that these two scales were normally distributed. To test our hypothesis, we

employed the following statistic methods: T-test, ANOVA, Bivariate Correlation, and Linear Regression

Analysis.

Findings

The mean score of the non-attachment scale was 4.37 (

colleagues’ (2010) study on adult participants in The United States of America, the mean obtained in that

study was much smaller for those participants who did not practice meditation (

those who did (

Effect of demographics on non-attachment and psychological well-being

Gender

An Independent Samples T-test yielded results indicating that there was an effect of gender on

non-attachment. Female participants had higher non-attachment scores (

counterpart (

well-being total score

Age

One-way ANOVA analysis did not demonstrate an effect of age on non-attachment,

1.72,

= 1.38,

psychological well-being scale. There was only significant difference in the Personal growth subscale,

over-55 groups. The 26-35 age group also has higher scores compared to the over-55 group (Table

Dharma practice arrangement

One-way ANOVA analyses showed that non-attachment scores were related to Dharma practice

arrangement (a community of people that we practice with),

practiced with a sangha had the highest non-attachment score (

significantly higher than practicing with friends (

(

significantly higher non-attachment than did those who practiced with friends (

members (

People who practiced in a Sangha had the highest psychological well-being scores (

.60). On the whole scale,

433) = 15.19,

434) = 10.96,

15.45,

.59) than those who practiced in a group of friends (

alone also reported higher self-acceptance scores (

3.81,

Those who practiced with their family members had higher purpose in life scores (M = 4.27, SD = .81)

than those practicing with friends (

It should be noted that, on the autonomy subscale, the one-way ANOVA did not yield any

significant difference between groups,

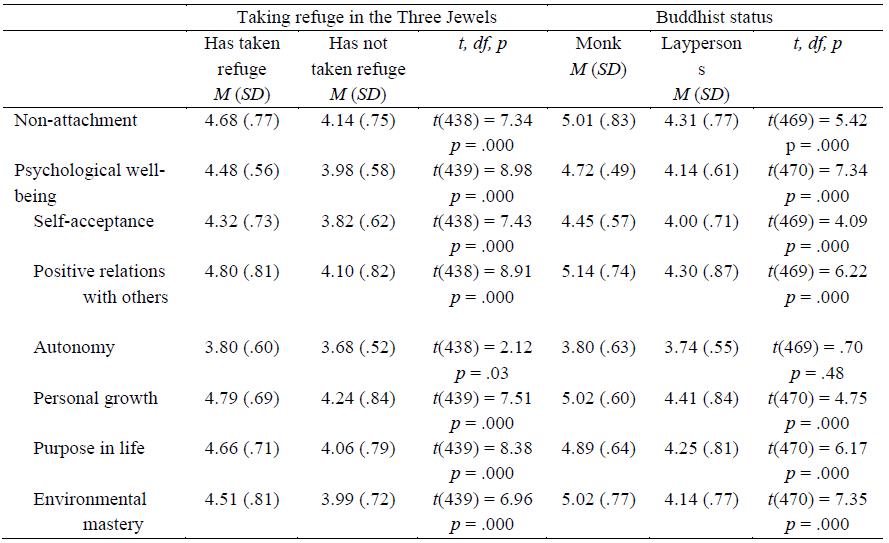

Taking refuge in The Three Jewels and Buddhist status

Participants who had taken refuge in The Three Jewels reported higher non-attachment and

psychological well-being scores, which are statistically significant. Monks in this study reported higher

non-attachment and psychological well-being scores (except on the Autonomy subscale) compared to

laypersons. An Independent Samples T-test demonstrated that the difference was statistically significant.

Detailed analysis is presented in Table

Frequency of practicing Dharma

Practicing Dharma includes a wide range of actions such as meditation, chanting, and praying.

One-way ANOVAanalyses showed that there was a significant effect of frequency of practice on non-

attachment,

People who practiced daily scored highest on the non-attachment scale (

on the psychological well-being scale (

had the lowest scores.

Those who practiced several times a year had lower non-attachment scores (

and psychological well-being scores (

score

one to four times a month (

autonomy scores of this group (

praying (

Relationships between non-attachment, psychological well-being and its components

Pearson Correlation Analysis showed significant positive associations between non-attachment

and each of the dimensions of psychological well-being scale as well as its full scale. The correlations

between non-attachment and self-acceptance, positive relations with others, personal growth, purpose in

life, and environmental mastery, were all moderate (from .49 to .52). However, the relationship between

non-attachment and autonomy was low:

full psychological well-being scale was moderately-strong:

**

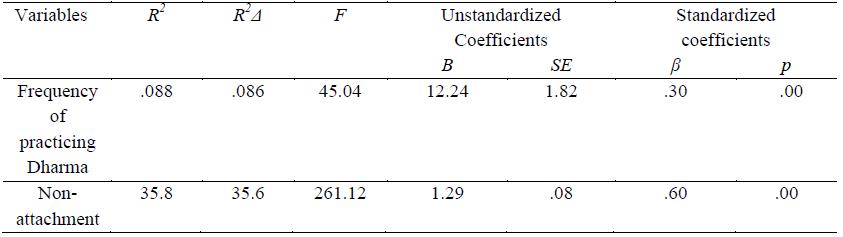

Factors predicting psychological well-being

Among demographic variables, only frequency of Buddhist practice was correlated to

psychological well-being

predictive ability of psychological well-being of frequency of practice and non-attachment. Results

showed that frequency of practice could predict 8.8% of variance of psychological well-being and of non-

attachment, 35.8%.

Conclusion

General discussion

In this study we find evidence to suggest that there are differences in non-attachment and

psychological well-being among Vietnamese Buddhists.

First; female participants had higher non-attachment than did male participants. The following

gender identity research suggests that gender differences are correlated with differences in self and

attachment. According to Bern (1974), the masculine sex-role is identified as "acting as a leader", while

the feminine sex-role is defined as "sensitive to the needs of others". Hofstede (2001) characterized

masculinity as ego-oriented, concentrated on materials, and to live in order to work. On the other hand, he

associated femininity as relationship oriented, focused on quality of life and relationships, and work is in

order to live. Therefore, it appears that masculinity is associated with possessions, conquering, and

enhancing ego, which represent attachment to external pleasure. These observations suggest one reason

why men had lower non-attachment than women.

Second, people who practiced in a Sangha had higher non-attachment than those who did not.

Also, people who practiced Buddhism everyday had higher non-attachment than those who did not., and

monks and people who had taken refuge in the Three Jewels, had higher non-attachment than lay people

and those who had not taken refuge. Practicing within a Sangha, practicing Buddhism, living a monastic

lifestyle, and taking refuge in the Three Jewels are actions of religious commitment. The results of the

present research are therefore supported by related studies that find a positive correlation between

religious commitment and feelings of happiness (Alaedein-Zawawi, 2015; McCullough & Worthington,

1999; McCullough & Willoughby, 2009; Toussaint & Webb, 2005), and between religious commitment

and mental health (Levin, 2010). Religious commitment may increase feelings of happiness by improving

self-regulation (McCullough & Willoughby, 2009) and a willingness to forgive ourselves and others

(McCullough & Worthington, 1999; Toussaint & Webb, 2005; Alaedein-Zawawi, 2015). Buddhist

teachings approach self-regulation from The Five Mindfulness Trainings, which are practices of

protecting life, social justice, responsible sexual behaviours, deep listening and loving speech, and of

mindful consumption. The practice of protecting life helps to stop war; practice of social justice brings

equality; practice of responsible sexual behaviours prevents suffering; practice of deep listening and

loving speech generates love and trust; practice of mindful consumption protects the body and mind.

Buddhists believe that practicing these teachings can help people to transform their greed, hatred and

ignorance, to increase compassion, and find happiness from the inside.

The results of the current study indicate that participants who practiced with groups of friends had

the lowest non-attachment scores and well-being scores. Sangha is an official religious organization,

which therefore has more religious commitment than a group of friends. We suggest that people who

practice with friends were often more focused on relationships within the group than on spiritual

transformation, and are less committed than those who practice with sangha or alone. This observation

can be associated to the notion of external religious orientation, that a person participates in religion to

feel protected (Allport & Ross, 1967).

Results also demonstrated that those who practiced praying only several times a year had the

lowest non-attachment and feelings of happiness. Represented by frequency of practice, this observation

adds further support for the argument for the potential for immense influence in religious commitment.

Third, non-attachment and well-being components such as, self-acceptance, positive relationships,

personal growth, purpose of life and environmental mastery, all positively correlated with each other.

Self-acceptance is conceived as having a positive attitude toward oneself, acknowledging and accepting

characteristics, including both wholesome and unwholesome aspects of oneself, and feeling satisfied

(Ryff, 2013). In Buddhism, the self is viewed as impermanent and always changing. Practicing

mindfulness in Buddhism helps people to accept phenomena, including the self, for the way it is in that

moment. Meditation helps people to experience and realise that there is no boundary between the self and

external phenomena (David, Lynn, & Das, 2013). Thus, successful practitioners do not attach to

seemingly permanent attributes of the self. Peacefulness happens at the very moment, and is not an

illusion of things in the past.

Having positive relationships includes satisfaction and trust within relationships, caring for others,

and generating empathy and deep emotions within relationships (Ryff, 2013). Ghose and Lynken (2004)

proposed that both attachment and separation are necessary in relationships. The idea of separation is the

non-attachment: no possession, no control, and feeling compassion and unconditional love in the spirit of

the Four Immeasurable Minds. Self-development is being open to new experience, recognizing one’s

behaviour, and then changing based on cumulative experience (Ryff, 2013). Johnstone and his colleagues

(2012) conducted quantitative research on Buddhists, Christians, Jews, Islamists and Protestants and

concluded that Buddhists were the most open-minded to new experiences. One can be open-minded only

when they cease perceiving the nature of phenomena with a limited view and construct a balanced view,

which permits non-attachment to phenomena.

Ryff’s (2013) ‘Purpose of life’ construct refers to perceiving that one’s life is meaningful and that

there are goals to strive for. By bringing freedom, non-attachment allows one to realise meaning in

ordinary actions and thus meaning in life. Some studies have mentioned this as the core function of

religions - to provide meaning to life (Martos et al., 2010; Diener et al., 2011). On the other hand,

environmental mastery is to deal with complex problems and to be capable of selecting choices or

creating situations that are suitable to one’s abilities, needs and values (Ryff, 2013). Non-attachment

allows people to find their own values and therefore escape from the influences of jealousy, worry,

obsession, compulsion and so on, and therefore to face the challenges of life (Sahdra et al., 2010).

Forth, the relationship between non-attachment, and independence and autonomy had the lowest

correlation and the average score of the independence and autonomy subscale was the lowest of all mean

scores. Autonomy is understood as being independent and capable of giving decisions, regulating oneself,

and feeling freedom. Those who had a high level of autonomy were determined and independent,

allowing them to a certain extent, to resist influences from others, to generate independent thoughts and

judgements, and to act on their own (Ryff, 2013). In order to account for low scores in this subscale,

Diener, Oishi, and Lucas (2003) once said that in collective cultures, being accepted and pursuing goals

that generate happiness for other people was integral to their notion of happiness. As East Asian cultures

emphasise relationships and social status (Markus & Kitayama, 1998), it may be the case that maintaining

harmonic relationships between people, promoting common wishes and thrift, are sources of happiness

(Lu & Gilmour, 2006). Shweder (1997), who discussed three models of ethics: Ethic of Autonomy, Ethic

of Community, and Ethic of Divinity, concluded that in collective cultures, ethic of community was the

most important factor for feelings of happiness. This implied that serving the community was more

important than serving oneself. This explanation seems reasonable as Vietnam is a country with a

collective culture.

More importantly, a great distinction can be observed between psychology and Buddhism.

Buddhism believes that the so-called self, which is usually referred as a permanent attribute of every

person, is a source of attachment and thus suffering. This is supported by the findings of a recent study, in

which it was discovered that those who used more self-referential terms tended to have more health

problems (Drakpa, Sunwar, & Choden, 2013). Therefore, Buddhism teaches its followers about emptiness

– there is no permanent self – and offers exercises that help people, through constant practice, to

understand this teaching and achieve happiness.

Lastly, it should be noted that while assessing the relationship with non-attachment and well-

being, the current research did not study behavioural mechanisms that could lead to non-attachment.

Grabovac and colleagues (2011) proposed a Buddhist psychological model for explaining the mechanism

in which practicing mindfulness reduces symptoms of mental disoders and improves psychological well-

being. In addition, Fryba (1995) also raised the need for practicing mindfulness to change perception,

emotions, and attention that is focused on desperation, hopelessness, inferiority, the self, and delusions of

emotions of the self. Together, those suggestions imply that mindfulness and mediation can serve as

factors explaing mechanisms that could lead to non-attachment.

Conclusion

This research provided evidence for a relationship between non-attachment and psychological

well-being in Buddhists. Results showed that non-attachment had greater influence on psychological

well-being in Buddhists who had more religious commitment, including practicing in Sangha, praying

daily, taking refuge in The Three Jewels, and ordaining, than in other groups. Results also suggested that

for Buddhists, autonomy as an approach involving controlling life, might not be an important criterion for

assessing psychological well-being.

Acknowledgments

This is to acknowledge funding from Vietnam National University, Hanoi. This study was conducted part of the project: “Religious beliefs and its effects to human well-being". Project number: QG.15.44.

References

- Ainsworth, M.D.S. (1985). Attachment across the lifespan. Bulletin of the New York Academy of

- Medicine, 61, 792-812.

- Alaedein-Zawawi, J. (2015). Religious commitment and psychological well-being: Forgiveness as a

- mediator. European Scientific Journal, 5, 117-141.

- Allport, G.W., & Ross, J.M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality

- and Social Psychology, 5, 432-443.

- Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social Indicators of Well-Being: American’s Perceptions of Life

- Quality. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Bradburn, N. M. (1969). The structure of psychological wellbeing. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

- Bradshaw, M., Ellison, C.G., & Marcum, J.P. (2010). Attachment to God, images of God, and psychological distress in a nationwide sample of Presbyterians. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 20, 130-147.

- Chah, A. (2011). The collected teachings of Ajahn Chah. Northumberland, England: Aruna.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Row. Dalai Lama (2000). The meaning of life: Buddhist perspective on cause and effect. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publication.

- Dalai Lama. (2001). Stages of meditation: Training the mind for wisdom. London, England: Rider. Dane, B. (2000). Thai women: Meditation as a way to cope with AIDS. Journal of Religion and Health, 39, 5-21.

- David, D., Lynn, S.J., & Das, L.S. (2013). Self-Acceptance in Buddhism and Psychotherapy. InM.E.

- Bernard (ed.), The Strength of Self-Acceptance: Theory, Practice and Research (pp. 19-38), Springer Science Business Media. DOI 10.1007/978-1-4614-6806-6_2

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542-575.

- Diener, E., Emmons, R.A., Larsen, R.J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 1-5.

- Diener, E., Lucas R.E., & Osihi S. (2005). Subjective well-being. The science of happiness and life satisfaction. In Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J. (Eds.), Handbook of Positive Psychology (pp. 63-71). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, Culture, and Subjective Well-Being: Emotional and Cognitive Evaluation of Life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 403-425.

- Diener, E., Tay, L., & Myers, D. (2011). The religion paradox: If religion makes people happy, why are so many dropping out? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 6, 1278-1290.

- Drakpa, D., Sunwar, D.K., & Choden, Y. (2013). GNH- Psychological Well-Being in Relation with Buddhism. Indo-Bhutan International Conference on Gross National Happiness, 2, 166-173.

- Ekman, P., Davidson, R.J., Ricard, M., & Wallace, B.A. (2005). Buddhist and psychological perspectives on emotions and well-being. Current directions in Psychological Sciences, 2, 59-63.

- Fink, C.K. (2013). Better to Be a Renunciant: Buddhism, Happiness, and the Good Life. Journal of Philosophy of Life, 2, 127-144 Finn, M., Rubin, & J.B. (2000). Psychotherapy with Buddhists. In P. Richards & A. Bergin (Eds.), Handbook of Psychotherapy and Religious Diversity (pp. 317-340). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Freud, S. (1913). Totem and Taboo. Resemblances between the psychic lives of savages and neurotics. New York: Moffat, Yard and Company.

- Fryba, M. (1995). The practice of happiness: Exercises & Techniques for developing mindfulness, wisdom and joy. Boston: Shambala.

- Ghose, L. (2004). A Study in Buddhist Psychology: is Buddhism truly pro-detachment and anti-attachment? Contemporary Buddhism, 5, 105-120.

- Grabovac, A.D., Lau, M.A., & Willett, B.R. (2011). Mechanisms of mindfulness: A Buddhist psychological model. Mindfulness [advance online publication]. DOI 10.1007/s12671-011-0054-5.

- Harris, E.J. (1997). Detachment and compassion in early Buddhism. Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society Hefti, R. (2011) Integrating religion and spirituality into mental health care, psychiatry an psychotherapy, Religions, 2, 611-627.

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences (2nd ed). Beverly Hills: Sage James, W. (1902). Varieties of religious experiences. New York: Longmans.

- Johnstone, B., Yoon, D.P., Cohen, D., Schopp, L.H., McCormack, G., Campbell, J., & Smith, M. (2012).

- Relationships among spirituality, religious practices, personality factors, and health for five different faith traditions. Journal of Religion and Health. DOI: 10.1007/s10943-012-9615-8 Joshi, S., & Kumari, S. (2011). Religious beliefs and mental health: an empirical review. Delhi Psychiatry Journal, 14, 40-50.

- Jung, C. (1938). Psychology and religion. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Keyes, C. L. M. (1998). Social wellbeing. Social Psychology Quarterly, 61, 121–140.

- Krause, N., & Hayward, R. D. (2013). Emotional expressiveness during worship services and life satisfaction: Assessing the influence of race and religious affiliation. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 16, 813–831.

- Levin, J. (2010). Religion and mental health: Theory and research. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 7, 102–115.

- Lu, L., & Gilmour, R. (2006). Individual-oriented and socially oriented cultural conceptions of subjective well-being: Conceptual analysis and scale development. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 9, 36-49.

- Markus, H. R. & Kitayama, S. (1998). The cultural psychology of personality. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29, 63–87.

- Martos, T., Thege, B. K., & Steger, M. F. (2010). It’s not only what you hold, it’s how you hold it: Dimensions of religiosity and meaning in life. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 863–868.

- McCullough, M.E., & Willoughby, B.L.B. (2009). Religion, self-control, and self-regulation: Associations, explanations, and implications. Psychological Bulletin, 1, 69-93.

- McCullough, M.E., & Worthington, E. (1999). Religion and the forgiving personality. Journal of Personality, 67, 1141-1164.

- McIntosh, D. N. (1995). Religion as schema, with implications for the relation between religion and coping. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 5, 1–16.

- Naidu, R.K., & Pande, N. (1990). On quantifying a spiritual concept: an interim research report about non-attachment and health. Abhigyan:The Journal of Foundation of Organisational Research, 1-18.

- Negovan, V. (2010). Dimensions of student’s psychological well-being and their measurement: Validation of a student’s Psychological Well Being Inventory. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 2, 85-104.

- Pargament, K. I., Koenig, H. G., Tarakehwar, N., & Hahn, J. (2004). Religious coping methods as predictors of psychological, physical and spiritual outcomes among medically ill elderly patients: A two year longitudinal study. Journal of Health Psychology, 9, 713-730.

- Park, C. L. (2005). Religion as a meaning-making framework in coping with life stress. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 707–729.

- Revheim, N., Greenberg, W.M. (2007). Spirituality matters: Creating a time and place for hope.Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 30, 307-310.

- Ricard, M. (2006). Happiness: A guide to developing life’s most important skill. New York: Little Brown. Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic 141–166. and eudaimonic well-being. Annual review of psychology, 52, DOI: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141 Ryff, C. (2013). Psychological Well-Being Revisited: Advances in the Science and Practice of Eudaimonia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83, 10–28.

- Ryff, C. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081.

- Sahdra, B,K., & Shaver, P.R. (2013). Comparing attachment theory and Buddhist psychology. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 23, 282-293.

- Sahdra, B.K., Shaver, P.R., & Brown, K.W. (2010). A scale to measure nonattachment: A Buddhist complement to Western research on attachment and adaptive functioning. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92, 116-127.

- Seligman, M. E. P., Parks, A.C., & Steen, T. (2006). A balanced psychology and a full life. In A.

- Huppert, Felicia, Baylis, N., Keverne, B. (Eds.), The science of well-being (pp. 275-283). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Shonin, E., Van Gordon, W., & Griffiths, M.D. (2014). The Emerging Role of Buddhism in Clinical Psychology: Toward Effective Integration. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2, 123–137 Shweder, R. A., Much, N. C., Mahapatra, M., & Park, L. (1997). The 'big three' of morality (autonomy, community, divinity) and the 'big three' explanations of suffering. In A. M. Brandt, & P. Rozin (Eds.), Morality and Health (pp. 119-169). New York: Routledge.

- Snyder, C. R. and Lopez, S. J. (Eds.). (2009). Oxford handbook of positive psychology, 2nd ed., New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Toussaint, L., & Webb, J. (2005). Theoretical and empirical connections between forgiveness, mental health, and well-being. In E. Worthington (Ed.), Handbook of forgiveness (pp. 349-362), New York, NY: BrunnerRoutledge.

- Tsai, J., Miao, F.F., & Seppala, E. (2007). Good feelings in Christianity and Buddhism: Religious differences in ideal affect. Society for Personality and Social Psychology, 33, 409-421.

- Unterrainer, H-F., Nelson, O., Collicutt, J., & Fink, A. (2012). The English version of the Multidimensional Inventory for Religious/Spiritual Well-Being (MI-RSWB-E): First results from British college students. Religions, 3, 588-599.

- Wallace, B.A., & Shapiro, S.L. (2006). Mental balance and well-being: Building bridges between

- Buddhism and Western psychology. American Psychologist, 7, 690-701.

- Wang, S-Y., Wong, Y.J., & Yeh, K-H. (2016). Relationship harmony, dialectical coping, and nonattachment: Chinese indigenous well-being and mental health. The Counselling Psychologist, 44, 78-108. DOI: 10.1177/0011000015616463 Whittington, B. L., & Scher, S. J. (2010). Prayer and subjective well-being: An examination of six different types of prayer. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 20, 59–68.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

27 January 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-019-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

20

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-283

Subjects

Child psychology, developmental psychology, occupational psychology, industrial psychology, ethical issues

Cite this article as:

Hang, N. T. M., & Ngan, D. H. (2017). Buddhist Non-Attachment Philosophy And Psychological Well-Being In Vietnamese Buddhists. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences - icCSBs 2017, January, vol 20. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 119-134). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.01.02.14