Abstract

Music education (ME) is not part of the core subjects in the school curriculum in Israel. Therefore, views concerning the value of music are significant for the inclusion of ME in the school curriculum. Israeli society is interwoven from various religions with varied points of view concerning music. The article presents the types and sources of religious attitudes towards music and ME. In the Jewish and Christian religions music practices are mentioned in the holly scripts and are therefore accepted as part of both religious and secular activities. However, in the Islamic religion very few music practices are mentioned in the holly script. Therefore, Islamic orthodox authorities' interpretations of the holy script resulted in the banning of many music activities. These bans which were adopted also by the Druze religion lasted for over a millennium. The diverse attitudes of the four main religious cultures towards music have had a different effect on the possibility to study music within each culture. These religious backgrounds clarify the diverse attitudes towards ME. There is a possibility that the disparity in the inclusion of ME is partly caused by these historical religious backgrounds related to views about music. These views may effect the actual musical opportunities of children in Israel.

Keywords: Musicmusic educationreligious music view

Introduction

Musical learning and experiences for children in Israel can be gained in various ways. Official music learning can be gained either through the educational system, through music conservatories and academies, or by life experiences in the community. Participation in music activities contributes to a general feeling of well-being.

Although music education is recognized as an important part of the general education it is not part of the core curriculum. In Israel, a child's religious affiliation may influence the availability of musical experiences and learning opportunities. The main religions in Israel are: Jewish, Christian, Muslim and Druze. These religions have diverse attitudes towards music and thus music education.

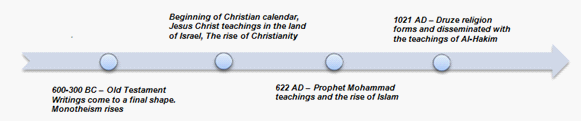

In the Jewish and Christian religions music practices are mentioned in the holly scripts and are therefore accepted as part of both religious and secular activities. However, in the Islamic religion very few music practices are mentioned in the holly script. Therefore, Islamic orthodox authorities from the 7th century and onwards interpreted, among other topics, the meaning of the Quran concerning music. These interpretations set bans over many musical activities, bans that lasted for over a millennium. The Druze religion adapted the Islamic bans.

These different religious attitudes concerning the value of music may have affected the inclusion of ME classes in the schools. The current situation today is that most of the Israeli elementary schools within the Jewish community include music classes. However, Israeli elementary schools within the Arab community that is mostly Muslim with a Christian minority are less likely to offer music classes. The lack of music classes and their individual and societal positive benefits associated with musical activities may effect not only the students but also the whole community.

Music and Music education

Music making is a natural behavior of human beings from birth to adulthood (Sloboda, Wise, & Peretz, 2005). Singing starts at a very young age and formulates into meaningful singing that accompany activities around the age of 2-3 years old (Young, 2002, 2006). School age children consider themselves as "playing-musicians" if they have a musical instrument available to play; they enjoy and create sounds even if they did not study these instruments with a teacher (Lamont, 2002). Secondary schools and high schools as well as conservatories provide teenagers with a possibility to play in musical ensembles, in a structured manner. These ensembles are composed of members at various ages. The experience to rehearse in such a group provides opportunities to consult each other in a relaxed atmosphere and without intimidation (Moore, Burland & Davidson, 2003). Playing bands where teenagers form their own groups with no guidance of teachers or adults has been called the "third environment" (Hargreaves & Marshal, 2003). In the "third environment" teenagers play together and learn from each other new techniques in a non-formal way. Once music engagement continues into teenage years, it may promote the development of musical identity. It has been found that participation in music making contributes to a general sense of individual well-being. For example, both ensemble playing (Kokotsaki & Hallam, 2007) and choir participation (Unwin, Kenny, and Davis, 2002) contributed to a general sense of well-being, i.e. ensemble playing contributed to the participants sense of self-achievement, increased their self-confidence and self-esteem, while choir singing promoted positive effects on mood.

Kokotsaki and Hallam (2007) listed the impact of musical activities as contributing to both musical skill achievements as well as to social and personal benefits. Musical achievements included improved technical and musical skills, while social benefits included making friends, learning to co-operate, and being a part of a team. Personal benefits included a sense of mental and social well-being (Kokotsaki and Hallam, 2007).

The realization of the importance of music is stated in a recent paper of the Department of Education in England (2012) that deals with their state ME plan for the next eight years from 2012-2020. This paper summarizes the benefits and importance of music activities.

Conflicting religious values regarding music education in Israel

ME in Israel today is not part of the core curriculum in schools. It is however one of several artistic subjects such as art and theater that, according to the Ministry of Education's core programs for the Kindergarten and the Elementary school, can be chosen as elective classes (Pre-elementary education division, 2005; Core program for the elementary school in the state of Israel, 2005). Obviously, the values attributed to ME by the headmaster of the school, as well as the community, are significant for its implementation in the school curriculum. In Israel, whose society is interwoven from various religions with varied points of view concerning music, these values are affected by the religious affiliation of both the headmaster and the community the school serves. Therefore, the positive values regarding ME that have been discussed previously may at times conflict with these religious affiliations, all of which will eventually affect whether or not there will exist music programs in the kindergarten or school and to what extent.

The attitude of four different religions in Israel towards music

The population in Israel includes approximately 8 million people. Of them about 75% (6.2 millions) are Jews, 21% (1.7 millions) are Arabs and 4% (about half a million) are Druze. The Arab population is combined of a majority of Muslims, 84% (1.4 millions) and a minority of Arab Christians (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2015). The attitude of the religious authorities of the four religions towards music and music learning affects the musical possibilities of each culture. These attitudes range from complete acceptance of music as exemplified in the Jewish and Christian religions with almost no special writings on the topic, to historical orthodox authorities ban on secular music as exemplified within the orthodox Muslim and Druze Religions.

The following overview describes the attitudes towards music and the musical practices of the different religions according to their historical appearance.

Judaism

Information regarding the music practices of the ancient Israelites, who were at that time nomadic tribes, derives from sources taken from the musical practices of the regional people – the Bedouins and from descriptions of early Islamic authors (Kraeling & Mowry, 1991) as well as from written source - the Old Testament. It is assumed that singing and playing simple musical instruments were common among the regional people (Kraeling & Mowry, 1991).

Responsorial singing (i.e. call-and-response: the leader sings a phrase and the congregation sings a response) is a common practice in tribal and folk music worldwide (ibid.). A description of an example for everyday singing among the Israelites during their travel to Israel through Moab specifies practices of responsorial singing. Old Testament (New International Version), Numbers, chapter 21:17 Then Israel sang this song:

The information from this verse points to the need for water in the desert, and the happiness celebrated with singing once finding it.

Various singing or music activities are also described in the Old Testament. They are either connected to certain celebrations or to practices that used to be performed in the Temple (Burkholder, Grout & Palisca, 2006). Music was always part of the Jewish life before and during Biblical time, as well as in the diaspora (Werner, 1991). Music activities of singing and playing as well as publications of singing books existed in the Jewish culture before the state of Israel was established (Ben Ze'ev, 2006). Today studying music is common and well accepted in the Jewish culture of Israel.

Christianity

The rise of Christianity and the formation of the New Testament as a continuum of the Old Testament, naturally gave place for musical practices. It seems that some similarities can be found in the musical practices such as melodic formulas of psalms singing, that resemble Jewish melodic formulas (Burkholder, Grout, & Palisca, 2006). In the New Testament, the first musical activity mentioned is hymn singing by Jesus and his disciples as can be seen in the New Testament (New International Version), Matthew 26:30 and Mark 14:26

From the fourth century on, informal public meetings for chanting prayers took place in basilicas (Burkholder, Grout, & Palisca, 2006).

An issue related to the joy of music arose with the influential church leaders known as "the Church fathers": St. Basil (ca. 330-379), St. John Chrysostom (ca. 345-407), St. Jerome (ca. 340-420), and St. Augustine (345-430). Most of them believed in the power of music to raise strong feelings. These feelings, according to their belief, should be channeled towards devotional spiritual worship and not channeled towards earthly simple joy that has nothing to do with divine worship (ibid.). The Church fathers did not approve of instrumental music for they believed that music without words does not direct the devotional thoughts into the right Christian direction. Old Testament references for harp and trumpets music were interpreted as an allegory. This view affected the Christian church musical practice that included only unaccompanied singing for over a millennium. Moreover, this was the first time that a ban was placed over some types of music.

It is interesting to note that during the eleventh century the monk Guido de Arezzo developed an innovative music notation system. This system enabled a greater precision in the study of chant singing which had until then relied on memorization abilities (Grout & Palisca, 1980).

Music was integrated into the Christian life from the very beginning and kept on being so by varied practices. The constant process of making music was natural in the Christian religion and therefore music became part of Christian life.

Islam

Music singing and playing has always been an integral part in the life of the people living in the Arabian Peninsula. During the pre-Islam period, called

The beginning of Islam is marked by concurring journeys of Prophet Mohammad and his disciples. These occupational journeys brought many new artists and musicians to the Arab peninsula (Shiloah, 1999) which led to the development of a rich musical tradition that became identified, mainly in the city of Medina, with life of pleasure (ibid.). Musicians' and poetry writers' creative energy was devoted mainly to love songs. Therefore, during this time period an association between music performances and permissive culture was created. Nevertheless, despite this somewhat negative association (at least in the eyes of the orthodox) the Quran does indicate that music was performed both in Prophet Mohammad's wedding as well as in his daughter's wedding (Hood, 2007).

The first version of the Qur'an was written shortly after Prophet Mohammad's death (632 AD), while the final version was set-up by the first half of the 10th century (Grandguillaume, 2010). During the 7th century two conflicting views concerning music performance evolved: one view saw no contradiction between Prophet Mohammad teachings and musical activities, whereas the other view banned all types of musical activities which had secular characteristics (Shiloah, 1999). This last view was adopted by the leading orthodox authorities, which strongly rejected secular types of music. Since these authorities could not find support against music practice in the prophet's teachings as written in the Qur'an, they started to interpret the text in a manner that would convey their point of view. It should be noted however that in the daily life of the Muslim community there is a lot of music playing and singing that is connected to life-events and ceremonies (Baily, 2006; Hood, 2007).

The view of banning music playing and studying seems to have influenced many people in the Muslim community for over a millennium. However in the last 150 years according to Abdel-Rahman Hamza (2014) a change has occurred whereby music has become more accepted in the cultural life of Arab countries such as Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Egypt. Moreover, nowadays both males and females participate in music performance.

Druze religion

The Druze is a monotheistic religion that originated in Cairo, Egypt, in the 11th century. The Islamic attitude of separating sacred from secular music prevailed and the Druze orthodox leaders adopted the view that prohibits secular music. As with Islam followers, orthodox people were likely to keep the ban concerning varied music activities, while others, not so highly orthodox, allowed such activities (Hood, 2007). According to Dana, Salman & Sulayman (1998), sacred prayer with singing occurs in the special holiday called

Current educational systems in Israel and its impact on music education

There are several educational systems in Israel that are structured according to language, religious affiliation and level of orthodoxy. Most of the schools are under the authority of the Ministry of Education. In general, the elementary schools are divided according to the language of the students: Hebrew or Arabic (there are also schools where other languages are spoken but they are a small minority). Most of the students that speak Hebrew are Jewish and they study in schools that maintain holidays according to the Jewish calendar. The majority (85%) of Jewish elementary schools have music programs (personal communication) as well as many of the kindergartens (the exact percentage is unknown due to disperse institutions dealing with this age).

Within the Arabic speaking students there are three different religious groups: Muslims, Christians and Druze. The Muslim and Christian Arabic speaking students are usually studying together. The spoken language in these schools is Arabic, while the holidays are maintained according to both Muslim and Christian calendars. There are also independent private schools of the Christian sector that have their own program (Ben Ze'ev, 2006). Druze students that reside in Druze villages (such as Daliyat al-Karmel and Yirka,) study in the village schools where the majority of the students are Druze. Other Druze students study in schools according to their place of residency.

The Israeli Ministry of Education decides upon the required fields and content of study which are part of a core curriculum to be taught by every school. In addition the Ministry allows for other fields of study as possible electives whereupon each school decides independently. The impact of this situation on the inclusion of music as one of the possible electives within Arab schools has been tremendous. In the past music classes were seldom included in the Arab school's educational program partly due to the historical attitude of the Muslim orthodox authorities, which as mentioned before was not appreciative towards secular music. However, the situation today is that a few schools within the Arab sector have begun to include music classes as part of their elective fields of study. In many cases these particular schools have headmasters that, regardless of their religious affiliations, support music learning due to their own personal educational ideology.

A major obstacle in incorporating music programs within the Arab schools is the lack of professional music teachers who speak Arabic. Therefore, there are instances where the only solution for the Arab schools to incorporate a music program is by hiring professional instrumentalist teachers whose native language is not Arabic. One of the problems of this type of solution is that most of these teachers are trained in the Western classical musical tradition, and therefore are lacking in both knowledge and musical repertoire that relate to their students' Arabic musical heritage.

During the past years, a few college music training programs have been trying to fill the need for Arab speaking music teachers. Such a program started during the 1980s in the Arab Academic College of Education in Haifa. The program lasted for a few years and was closed later on (Ben Ze'ev, 2006). Current programs exist in the Jerusalem Music Academy (JMA) and in the Levinsky College of Education (LCE).

The current situation in Israel is that while several music programs are offered in the secondary and high school level of the Jewish educational system, hardly any are available in the Arab sector (personal communication). The difference between the Jewish and the Arab sectors may be seen also in the availability of private music studies. Whereas in most of the cities conservatories and musical centers for professional musical instrumental playing are available for both Jewish and Arab populations, this availability differs in rural areas. Thus, for the Jewish population, most of the rural areas have some form of music centers that provide private music practice. However, for the Arab society that resides in rural areas, the situation is different and availability of music instruction is lower and it is affected by several variables: religious attitude towards music and music activities, financial possibilities, and political issues relating to education in general (Ben Ze'ev, 2006).

Discussion

The aim of this paper was to summarize several views that relate to the existence and facilitation of ME and music activities in Israel. One of the conclusions is that views in Israel concerning the value of music activities and ME are influenced by religious and cultural affiliation. Music learning in Israel is well accepted among Jewish and Christian people. Learning music for Muslim and Druze people in Israel raises the influence of the historical conflict that was between orthodox views and more liberal views relating to the value of music. The orthodox authorities supported music making only for religious purposes since other music related activities were still looked upon by them as being associated with bad-culture and permissive behavior. This view originated during the 7th century and lasted for over a millennium.

These views that were part of the Muslim traditional norms affected the inclusion of music classes in the Arab schools in Israel. The positive values regarding ME in Israel may conflict with the religious affiliations of the school and the community. These factors may affect whether there will be music programs in the school and to what extent, or not.

This reality can be seen in the current situation in Israel. For the majority of the Jewish students in the Israeli elementary schools music classes are offered, while only for a minority of the Arab students in the Israeli elementary schools music classes are offered. The present situation deprives many Arab school students from studying music. This lack of opportunity might affect not only the students but also the whole community due to the lack of individual and societal benefit effects associated with musical activities.

Moreover, there is also a connection between geographic location and music learning possibilities. Arab music students that come from central cities such as Nazareth, Haifa, or Jerusalem, as well as from some rural areas that have music teachers, have had the opportunity to study and play a musical instrument during childhood. However, Arab music students that come from rural areas with no music teachers usually have a musical background that was randomly picked up both by watching and listening to community members making music as well as through participation in community ceremonies.

These differences obviously affect the music level of those students who apply for a bachelor's degree in music or ME. However, regardless of these differences, all students including those students from the rural areas that successfully graduate from these programs are the ones that can make a significant change in their society by teaching music. The benefits of running a music program in a local school is the exposure of young school children as well as their families to music, thus creating a community involved in music.

The stated motivations of two Arab college students exemplify their belief and conviction to create such a change.

One student stated in a conversation:

"I want to see teenagers in my village meeting together to play music instead

of walking around the streets, and I will make it happen".

Another student talks about the power of making music within a group:

"I want to create circles of women of all ages that would meet together and

sing. That (i.e. activity) will start a process that they will hear their voices

and would dare to start speaking".

Conclusions

Music activities and ME are well ingrained in the Jewish Israeli society. They were and are well accepted in the Christian society in Israel, while they become only recently accepted among the Muslim and Druze societies in Israel. Even though there are regular music classes in many of the Jewish elementary schools, there is still a lack of regular music classes in many of the Arab elementary schools that include students of the three religions: Muslims, Christians and Druze. There is a possibility that the disparity in implementation of music classes in the schools’ curricula is partly caused by the historical background related to the different religious views about music. A process for promoting music classes in the Arab community depends both on the will of the school headmasters to include music classes as part of the school's curriculum, as well as having Arabic speaking music teachers who can teach music in the schools. A general realization of the value of musical activities that occurred in the last century in the Arab countries, which continues to this day, contributed to the promotion of music as a positive activity that is generally well accepted by the society.

References

- Abdel-Rahman Hamza, D. (2014) Parents' perceptions of music classes in an elementary school: case Arabic elementary school in northern Israel. Unpublished master's thesis, Levinsky College of Education, Tel Aviv, Israel (Hebrew).

- Baily, J. (2006). Music is in our blood: Gujarati Muslim musicians in the UK. Journal of ethnic and migration studies, 32(2), 257-270.

- Ben Ze'ev, N. (2006) Music teaching at the schools of the Palestinian-Arab community in Israel:history and current aspects. Unpublished master's thesis, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel (Hebrew).

- Burkholder, J. P., Grout, D. J. & Palisca, C. V. (2006) A history of Western music (7th ed.). NY: W.W.

- Norton & Company.

- Core program for the elementary school in the state of Israel (2005) (Hebrew). Retrieved from: http://cms.education.gov.il/

- Dana, N., Salman, F., & Sulayman, B. (1998) The Druze. Ramat-Gan, Israel: Bar-Ilan University. Retrieved from: /www.kotar.co.il.ezproxy.levinsky.ac.il/

- Department of education (2012) The Importance of Music. England. Retrieved from: https://www.gov.uk/government/

- Grandguillaume, G. (2010) The forgotten cultures of the Qur'an. International Congress of Phonetic Sciences. DOI:

- Grout, D. J., & Palisca, C. V. (1980). A history of Western music. NY: W.W. Northon & Company.

- Hargreaves, D. J., & Marshall, N. A. (2003). Developing identities in music education. Music Education Research, 5, 263-274.

- Hood, K. (2007) Music in Druze life. UK: Druze Heritage Foundation.

- Kokotsaki, D. & Hallm, S. (2007). Higher education music students' perceptions of the benefits of participative music making. Music Education Research, 9, 93-109.

- Kraeling, C. H. & Mowry, L. (1991). Music in the Bible. In E. Wellesz (Ed.) Ancient and oriental Music (pp.283-296). NY, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Lamont, A. (2002). Musical identities and the school environment. In R. MacDonald, D. Hargreaves & D. Meill (Eds), Musical Identities (pp. 41-59). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Moore, D. G., Burland, K., & Davidson, J. W. (2003). The social context of musical success: a developmental account. British Journal of Psychology, 94, 529-549.

- Pre-elementary education division (2005). http://cms.education.gov.il/

- Shiloah, A. (1999). Music in the world of Islam. Jerusalem, Israel: Bialik Institute (Hebrew).

- Sloboda, A. S., Wise, K. J., & Peretz, I. (2005). Quantifying tone deafness in the general population. In G. Avanzini, S. Koelsch, L. Lopez, & M. Majno (Eds.) The Neurosciences and Music II: From Perception to Performance (pp. 255-261). NY: New York Academy of Sciences

- Unwin, M. M., Kenny, D. T. & Davis, P. J. (2002). The effect of group singing on mood. Psychology of Music, 30, 175-185.

- Werner, E. (1991) The music of post-biblical Judaism. In E. Wellesz (Ed.) Ancient and oriental Music (pp. 313-316). NY, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Young, S. (2006). Seen but not heard: young children improvised singing and educational practice. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 7, 270-280.

- Young, S. (2002). Young children's spontaneous vocalizations in free-play: observations of two-to-three-year-olds in a day-care setting. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 152, 43-53.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

22 December 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-017-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

18

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-672

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Cahn, R. P., & Rusu, A. S. (2016). Diverse Attitudes of Religious Cultures in Israel towards Music and Music Education . In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development - ERD 2016, vol 18. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 552-561). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.12.68