Abstract

The aim of the article is to present part of a research study investigating development of social communication patterns among children in a multi-dialogical kindergarten. This was a mixed method research. The qualitative part of the research was conducted in two parallel phases: conducting participatory observations on 25 kindergarten children learning according to the MDA; some of these observations were recorded in writing while others were video-filmed and transcribed. In addition, the researcher conducted semi-structured interviews with 15 kindergarten teachers, seven of whom work according to the MDA and eight who work according to the traditional educational approach. To supplement the qualitative study, a closed-ended quantitative questionnaire was constructed. This questionnaire was administered to 130 kindergarten teachers, 73 of whom were teachers working according to the MDA or undergoing training for the MDA and 57 teachers working according to the traditional approach. The data from this part were analysed statistically. The article focuses on philosophical discourse among kindergarten children. The research was based on participatory observation of discourse among children on a topic which interested them. They presented their theories about the topic and using developmental thought, they expanded them. This led to peer learning, re-examination of theories and participation of the teacher. The teacher was thus regarded as a participant in the discourse rather than the only source of knowledge.

Keywords: Multi-dialogical approachchildren's participationphilosophical discourse in kindergartenchildren’s theories

Introduction

This work deals with the use of the multi-dialogical approach (MDA) in the kindergarten. Its aim is to examine the connection between the MDA and the development of social and communicative skills of kindergarten children like discourse and philosophical discourse. One of the purposes of preschool education is to allow the child to grow and to evolve into a person involved in society, who has the ability to judge and criticize and is a curious independent thinker, demonstrating initiative. The fundamental idea of multi-dialogical education, which is at the basis of this work, is that a child who learns about his world out of an inner interest will evolve into that type of a person. The aim of this study is to examine the central aspects of this educational method namely, the patterns and social communicational processes of children who learn in a multi-dialogical kindergarten.

The contribution of discourse to the dialog is reflected by the fact that during discourse, the participants can exchange ideas, listen to other ways of thinking, investigate a problem in depth and understand its complexity, consolidate assumptions and apply them to external criticism. Another aspect of discourse is the philosophical discourse in which children raise questions regarding the world around them, and independently investigate their answers and theories, while acquiring discourse capabilities.

The qualitative part of the research was conducted in two parallel phases: filmed and transcribed participatory observations of 25 kindergarten children learning according to the MDA. In addition, the researcher conducted semi-structured interviews with 15 kindergarten teachers, seven of whom work according to the MDA and eight who work according to the traditional educational approach. To supplement the qualitative study, a closed-ended quantitative questionnaire was constructed and given to 130 kindergarten teachers.

Literature review

The dialogical education approach argues that optimal learning is performed when it stems from the child’s internal curiosity (Fisher, 2007).

Multi Dialogical Approach in the kindergarten

The Israeli kindergarten is an educational-learning framework, aiming to promote children’s development to be active, initiating, decisive, independent and social individuals (Levine, 1989; Ministry of Education, 2010). Multi-dialogical education is based on the principles of dialogical education. Dialogical education is development of the culture of research among the children while the educator listens to the children, asks them questions, mediates and documents their activity (Fiore & Suares, 2010). This enables the children to conceptualize phenomena and situations which arise from activity in their environment (Caspi, 1979). Multi-dialogical education is characterized by the fact that the children are partners in decision-making about how the kindergarten operates, not only in the realm of studies but in all aspects. This decision-making, based on negotiation between the kindergarten teacher and the children (Efrat & Ungureanu, 2015), includes discourse about behavioral norms, focuses of activity and how these should be advanced, holidays and how they should be celebrated and the kindergarten way of life.

According to the multi-dialogical approach, attentiveness is expressed in every aspect of the kindergarten and not only in spoken words. In practice, this approach is reflected by partnering the children in planning kindergarten activities, by letting them instruct their peers in small groups and in the general meeting, by encouraging them to give feedback to other children on instructed activities, and by the kindergarten teacher’s personal meeting with them to plan activities that will be presented by them (Firstater & Efrat, 2014).

Philosophical discourse

With regard to the age appropriate for initiating philosophical discourse, it has been found that even kindergarten children have the ability to conduct a philosophical discourse (Cohen, 2008). There are many similarities between the components of philosophy and education (Lipman & Sharp, 1985). They both focus on investigation, study, examination, reaching conclusions, dialog, and are both based on critical thinking and questioning. In sum, there is no way to separate education and philosophy and moreover, it can be argued that philosophy is education. Thus, developing philosophical discourse with children helps their approach to life in both intellectual and social ways (Cohen, 2008).

Philosophical discourse helps promote the children's ability to ask questions and explore the world. There is agreement among philosophers that this dialog develops communications skills, curiosity and cooperation among children (Fisher, 2007).

The aim of philosophical discourse with children is not to teach children philosophy, but rather to encourage them to create their own philosophy, which will be exploratory, dynamic, investigational, and creative (Cohen, 2008). During a philosophical discourse, an experience is shared and meaning is investigated. As philosophical discourse is based on attentiveness, listening, understanding, empathy, and joint activity (Fisher, 2007), it can be argued that this discourse develops awareness by the children of themselves and other circle participants. (Lipman, 2003).

The key to a successful dialog is listening, self-recognition and mutual understanding, but not necessarily mutual agreement (Lyle, 2008). Philosophers who deal with dialog and education agree that the basic characters of dialogic approach in education are: negotiation between participants in the educational process, attentiveness to children’s theories which be used as learning bases, understanding that the meeting of children and educators is the main learning process and that knowledge is only a learning tool (Aloni, 2008; Forman & Fyfe, 1998; Lasri, 2004).

Hypotheses

Considering the findings in the literature review, the hypotheses are as follows: The research hypothesis: 1. Differences will be found in social and communicative patterns among children educated in multi-dialogical kindergartens and children educated in traditional kindergartens. 2. Differences will be found mainly in the manner of discourse and the extent to which philosophical discourse is conducted in multi-dialogical kindergartens and children educated in traditional kindergartens.

Methodology

A mixed-methods approach using quantitative and qualitative data was chosen. Part of the qualitative research is an ethnographic study. This has included the use of filmed and transcribed participatory observations performed in a multi-dialogical kindergarten. These observations are meant to clarify the different types of kindergarten children's interpersonal communication. In addition, the research employed semi-structured interviews and closed questionnaires. Qualitatively, semi-structured interviews were administered to a small number of kindergarten teachers in order to examine the application of the multi-dialogical approach (MDA) in kindergartens.

In the quantitative part of the research, closed questionnaires were administered to a large number of kindergarten teachers in order to identify and explore ways to implement the MDA in kindergartens.

The qualitative research data was analyzed by content analysis based on categories. The quantitative data was analyzed statistically using t-test variance tests in a purposeful sample.

The research population included three groups: The first group included 25 children aged 3-6; the second group included 15 kindergarten teachers and the third group included 130 kindergarten teachers. The participants were selected in a purposive sample method (Bocos, 2007; Stake, 1995; Shkedi, 2003; Mason, 1996).

Findings

Analysis of the qualitative data from the participatory observations conducted in the multi-dialogical kindergarten revealed that the children learn to discuss things independently. The children manage to discuss a problem that worries them without the intervention of the teacher but solely in her presence. As a result they learn the rules of discussion in practice, under the teacher’s guidance. The children negotiate allowing them to internalize these rules.

The following example from Participatory Observation 1 relates to the children exercising the rules of discussion. Shani (5.1) turned to the teacher and asked her if all the kindergarten children could hold a discussion on a subject that worried her. The conversation went like this:

Teacher: “Children, Shani came to me … and she asked us to discuss something that concerned her on the subject of … if anyone has anything to say they are invited to do so. I remind you of the rules – only one person can speak at a time”.

Shani (5.1): “And we also don’t interfere when someone is talking”.

Nira (5.2): “And we don’t need to raise our hands”.

Social conflicts between children are resolved in the multi-dialogical kindergarten through negotiations between them. The children learn to help their friends to resolve disputes independently. An example appears in Participatory Observation 5 in which there is a game activity led by a girl for all the kindergarten children. They were asked to arrange themselves in a circle:

Yotam (4.0): “I don’t want to hold Ofri’s hand”.

Ofri (4.2): “Yotam won’t give me his hand”.

Dalit (5.0) turning to Yotam: “Will it help you if Matan is next to you?”

Yotam (4.0) nods his head in agreement, Matan and Ofri change places in the circle.

Analysis of the qualitative data from the interviews with the teachers supports what was seen in the participatory observations. It appears that “the children learn how to converse and they learn the rules of discussion and how to speak to one another and how to solve problems and how to pay attention” said Liron. Thus, as Ora notes, they actually “acquire skills” and Noam adds that this means that the “inter-personal discussion and the general discussion is at a far higher level when using this [dialogical] approach”. Michal indicates that “this MDA is actually one large discussion”, whereby “the children are exposed to the concept of discussion, and they learn and know how to use it” adds Irit.

It was found that philosophical discussion is part of the discourse that is conducted in a kindergarten working according to the MDA. Philosophical discussion is a discussion that arises because “children bring all sorts of theories, they raise all sorts of questions in the kindergarten … and we conduct a discussion on the question. It’s actually a philosophic question that they raise” explained Irit. “The fact that they know how to give answers to a question that they raise in such a philosophical discussion is something they learn from the MDA” added Judith.

The films also show that the children raise philosophical questions, discussing them independently and expressing philosophical thoughts derived from the questions, as can be seen in this excerpt from Film 5:

Afiq (5.2): “I wanted to ask if you think that someone lives in the sky?”

Ronen (4.5): “I think they do. God”.

Dalia (5.0): “If there is no God then who gave birth to our parents?”

Noia (4.8): “Ah, that’s right … but our grandparents gave birth to our parents…”.

Dan (5.5): “So who created the world … only God can”.

Dalia (5.0): “I think it’s not like that, it’s not God and I don’t think there is any God who lives in the sky”.

It seems that discussion in general, and in particular philosophical discussions are types of dialog that take place in kindergartens working according to the MDA. They have clear rules that the children learn to assimilate as part of the social communication patterns developing in the kindergarten.

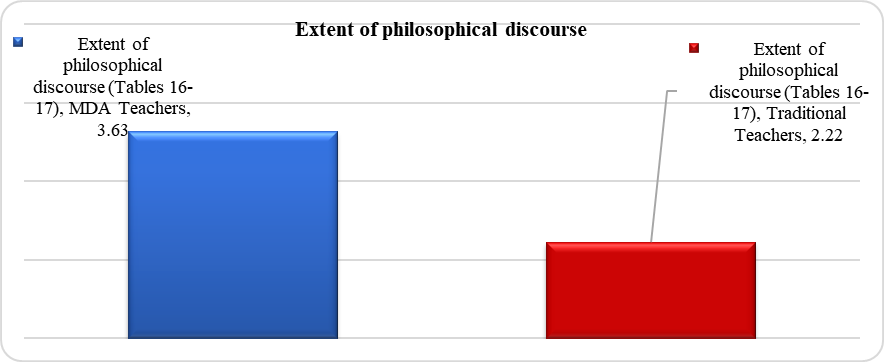

Analysis of the quantitative data from the questionnaire revealed that significant differences were found in the extent of philosophical discourse reported by MDA teachers and reports of traditional teachers. Thus the extent of philosophical discourse was found to be highest in the reports of the MDA teachers in comparison to the reports of the traditional teachers (3.63 in contrast to 2.2 respectively, t=7.83, p<0.01). More specifically, the extent of philosophical discourse in the kindergarten according to different characteristics examined in the questionnaire was found to be significantly higher in the reports of MDA teachers in comparison with the reports of the traditional teachers.

Discussion

Regarding the differences between the MDA and the traditional kindergartens, hypothesis 1 proposed that differences would be found in social and communication patterns between children educated in multi-dialogical kindergartens and children educated in traditional kindergartens. Hypothesis 1was confirmed.

The findings reveal a connection between the MDA in kindergartens and the development of social-communicative patterns in the kindergarten children.

Discourse in general and philosophical discourse in particular emerged as types of dialog employed in the MDA. When philosophical discourse is involved, different viewpoints on one subject are presented and the children are exposed to the possibility of examining a particular subject from multiple angles and the fact that there is not just one way of thinking. On this point, previous research shows that, in general, children have the ability to state their own opinion and attitudes (Harcourt, 2011), and that it is possible to teach kindergarten children to discuss things (Mercer & Dawes, 2010; Mercer & Littleton, 2007). However, to do this requires the teacher’s awareness and the teacher and children need to train their participation in discourse (Wells, 1986; Wells & Ball, 2008). In practice, during the discourse the participants need to learn the rules: timing – when to enter the discourse and say your piece, speaking without interrupting, respectful consideration of other participants even if they contradict their own opinions (Blum-Kulka 2008; Cohen, 2008) and the use of expressions such as “in my opinion” or “I think” (Callander, 2013). With regard to philosophical discourse, it seems that children’s philosophical investigation is based on their natural curiosity, so that they develop the ability to ask questions (Fisher, 2007).

In the multi-dialogical kindergarten, social communication patterns such as the ability to discuss in a manner that involves attentiveness and tolerance for others, without judgment, while demonstrating restraint and acceptance of the opinions of others is shaped and acquired with the help of coaching in the rules of discourse in general and philosophical discourse in particular. Also, patterns such as autonomy and empathy for others are expressed through the “active listening” that is exercised by the teacher and the children. In summary, it is concluded that the way children are equipped with social communication patterns depends on the teacher’s approach that, unlike the approach of the teacher in the traditional kindergarten, facilitates the expression of the children’s initiatives and fields of interest. The way to equip the children with social communication patterns such as flexibility and thinking outside the box depends on the teacher’s own ability to do this and thus the teacher acts as a model.

As proposed in hypothesis 2, significant differences were found in the extent to which philosophical discourse is conducted in the kindergarten between the reports of the MDA teachers and reports of the traditional teachers. Hypothesis 2 was confirmed.

According to the MDA, philosophical discourse is a structured part of the learning curriculum. Underpinning this type of discourse is the belief that there is no need to teach the children an opinion; rather they should be allowed to ask questions, to think about their own theories, to test them, to try to draw conclusions from this process and in this way to investigate and develop their thoughts. In contrast, in the traditional approach philosophical discourse only occurs occasionally and randomly and not as part of the structured learning curriculum.

In summary, in the multi-dialogical kindergarten, social communication patterns such as ability to ask questions, to test things from different angles, to draw conclusions and to make decisions, to consider others and to be attentive are shaped through philosophical discourse that is a structured part of the kindergarten’s learning curriculum.

Research significance

The significance of the research lies in its ability to inform a change in the practical perception and approach to early childhood education in the context of the multi-dialogical kindergarten, by offers foundation for promotion and shaping of social communication patterns among early childhood children learning in the multi-dialogical kindergarten.

The teacher needs to increase her own awareness regarding the substance of attentiveness in the educational act, and to learn how to apply this at her own personal level and in the kindergarten.

Limitations

The qualitative study was ethnographic, providing a low level of objectivity. Thus, the researcher used a wide range of sources of information to increase validity. In addition, in the participatory observations, the researcher’s presence could influence the participants’ behavior. However, in the many hours of observation, the participants became used to the researcher and ignored her. In the semi-structured interviews, participants tend to want to please the interviewer. The researcher thus avoided judgmental reactions.

Conclusion

Conclusions regarding the differences between the MDA and the traditional kindergartens

Hypothesis 1 was: Differences will be found in social and communication patterns between children educated in multi-dialogical kindergartens and children educated in traditional kindergartens. Hypothesis 1 was confirmed.

It seems that the children’s attentiveness to their friends is a social-communication pattern that is acquired in the multi-dialogical kindergarten and receives an important place through the coaching and guidance of the teacher. More specifically, it is concluded that the way in which children are equipped with social-communication patterns depends on the teacher’s approach that, unlike the approach of the teacher in the traditional kindergarten, facilitates the expression of the children’s initiatives and fields of interest.

Conclusions regarding the social-communication patterns

Hypothesis 2 was: Differences will be found mainly in the extent of philosophical discourse. Hypothesis 2 was confirmed.

In a similar spirit, patterns of, developing abilities, drawing conclusions, independent thinking and peer learning are shaped as implications of learning according to the MDA. The children’s consideration of their friends, expression of their opinions and feelings in a group, identifying difficulties and strengths, and respecting the time needed for deep thinking are acquired through “mediated learning”.

It can be seen that social-communication patterns such as taking responsibility for discourse, paying attention to others and the skills of group discourse are shaped in the multi-dialogical kindergarten as a result of the manner of discourse in the meetings guided by the teacher and this enables the children to learn when to enter the discourse, and they are not managed by her. In their “philosophical discourse” the children propose particular topics to discuss in the kindergarten. Additionally, the ability to ask questions, to examine things from different angles, to draw conclusions and to make decisions, to consider others and to pay attention are realized through philosophical discourse that is a structured part of the learning curriculum in the multi-dialogical kindergarten.

References

- Aloni, N. (2008). Introduction. In N. Aloni, (Ed.), Empowering dialogues in humanist education (pp. 16-47). Tel Aviv, IL: Hadekel. [Hebrew]

- Blum-Kulka, S. (2008). Language, communication and literacy: Outlines for the development of literate discourse. In P. S. Klein & B. Yablon (Eds.), From research to action in early childhood education (pp. 117-154). Jerusalem, IL: Keter.

- Bocoş, M. (2007). The Theory and Praxis of Pedagogical Research. [Teoria şi practica cercetării pedagogice]. Cluj-Napoca: Editura Casa Cărţii de Ştiinţă

- Callander, D. (2013). Dialogic approaches to teaching and learning in the primary grades. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Victoria).

- Caspi, M. (1979). Education tomorrow. Tel Aviv, IL: Am Oved. [Hebrew]

- Cohen, A. (2008). Small philosophers, philosophy for children and with children. Haifa, IL: Amatzia. [Hebrew]

- Efrat, M. & Ungureanu, D. (2015). Is the egg spoiled? A big question from a small child. Proceeding of the International Conference on Education Reflection and Development (pp. 294-312). Romania: Cluj-Napoca.

- Fiore, L. & Suares, S. C. (2010). This issue. Theory into Practice, 49(1), 1-4.

- Firstater, E. & Efrat, M. (2014). Social communication patters of children in a kindergarten operating according to the dialogical education approach. Rav Gvanim, Research and Discourse, 14, 11-48. Under the auspices of “Study and Research in Teacher Training”, Jerusalem: Ministry of Education and Gordon Academic College of Education. [Hebrew]

- Fisher, R. (2007). Dialogic teaching: developing thinking and metacognition through philosophical discussion. Early Child Development and Care, 177, 615–631.

- Forman, G. & Fyfe, B. (1998). Negotiated learning through design, documentation, and discourse. In C. Edwards, L. Gandini & G. Formaneds (Eds.), The hundred languages of children: The Reggio Emilia approach- advanced reflections (pp. 239-260). London: Ablex.

- Harcourt, D. (2011). An encounter with children: Seeking meaning and understanding about childhood. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 19(3), 331-343.

- Lasri, D. (2004). A place to grow. Rosh Pinna. IL: Haofen Tivai. [Hebrew]

- Levine, G. (1989). Another kindergarten. Tel Aviv,IL: Ach. [Hebrew]

- Lipman, M. (2003). Thinking in education. Cambridge University Press.

- Lipman, M. & Sharp, A. M. (1985). Ethical inquiry: International Manual to accompany 'Lisa', Montclair, NJ: Institute for the Advancement of Philosophy for Children.

- Lyle, S. (2008). Dialogic teaching: Discussing theoretical contexts and reviewing evidence from classroom practice. Language and Education, 22, 222-240.

- Mason, J. (1996). Qualitative researching. London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Mercer, N. & Dawes, L. (2010). Making the most of talk: Dialogue in the classroom. English Drama Media, 16, 19-25.

- Mercer, N. & Littleton, K. (2007). Dialogue and the development of children’s thinking: A sociocultural approach. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Ministry of Education (2010). Guidelines for educational work in kindergartens. Jerusalem, IL: Department for Pre-Primary Education, Ministry of Education. [Hebrew]

- Shkedi, A. (2003). Words that attempt to touch, Qualitative research - Theory and implementation. Tel Aviv, IL: Ramot. [Hebrew]

- Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Wells, G. (1986). The meaning makers: Children learning language and using language to learn. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Wells, G. & Ball, T. (2008). Exploratory talk and dialogic inquiry. In N. Mercer & S. Hodgkinson

- (Eds.), Exploring talk in school (pp. 167-184). London, UK: SAGE Publications, Ltd.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

22 December 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-017-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

18

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-672

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Efrat, M. (2016). Philosophical Discourse of Children in the Multi-Dialogical Kindergarten. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development - ERD 2016, vol 18. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 389-397). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.12.47