Abstract

Stories have a universal appeal and their effectiveness as a learning tool has already been demonstrated. For the social-emotional development of students we consider therapeutic stories as an effective method to shape the way they interact with the world and to reveal the essential aspects of themselves The article presents the role of the therapeutic stories in the social-emotional development of second grades pupils. Our research objectives were to implement during the personal development classes, an intervention program based on therapeutic stories for II grade pupils and also to contribute to the social-emotional development of these pupils. As research methods we used the questionnaire to identify the level of social-emotional development, and the pedagogical experiment with an inter-subject design. The findings of the research indicate that students developed in a large extend, during the formative intervention: the interaction skills with adults and with peers, also the ability to accept and respect diversity, the pro-social behavior, the self-concept and the emotional control.

Keywords: Therapeutic storiessocial-emotional developmentpersonal development lessonswell-beingbehavioral changes

Introduction

Families and schools have an essential role in developing and maintaining well-being, but often it is these learning environments which create conditions that undermine students‘ self-confidence, restrict or censor autonomy, enjoyments and everyday pleasures, inducing threatening perceptions of the world and life (Băban, 2001). Metaphors and therapeutic stories have the role of a true catalyst of resources. Therapeutic metaphor or fairy tales, stories, parables, aphorisms and other forms of communication that have a therapeutic - metaphorically - role: capture attention and create conditions for a therapeutic relationship; provides the opportunity to identify with images, ideas, symbols, wishes, aspirations; helps clients understand and unwind tension; suggest possible solutions.

Metaphors and therapeutic stories, conceptual explanations

According to G. Burns (2012) therapeutic stories contribute to restoring, enhancing or amplifying mental or emotional well-being. The therapeutic stories are designed to change attitudes, emotions and behavior patterns, so as to facilitate our adaptation to the conditions and circumstances of life. Therefore, stories transmit not only a way of life, a philosophy of life, but they provide dynamic and lasting relationships between mind, body, soul and the environment.

In psycho-biology (Pert 1995, 1987; Rossi, 1993; Rossi & Cheek, 1998) states that the therapeutic stories which change something about the way we think or feel, also induces changes in our mind-body process, like changing the respiration level, in muscle movements and heart beat.

The therapeutic story or metaphor is not just a linguistic phenomenon, but a less abstract concept or system of concepts, that helps us understand formal concepts and judgments (to understand an abstract topic in more concrete terms or concise). Based on the similarity but especially on the possible correspondence between our experiences, metaphor allows us to talk about experiences that can not be described literally and to express opinions in a concise and indirect way.

Peivio (1993) said that metaphors are "cognitive processes that occur within a cognitive representations and network memory. Understanding metaphor implies a long-term retention of information associated with metaphorical terms." The metaphor is a linguistic but also a cognitive and emotional structure and it is transmitted and received at these levels.

Lakoff (1980) states that metaphors are cognitive structures that have a role in processing information and they are of several types: ontological metaphors that are born of body experience and relate to inanimate objects; orientations metaphors that provide guidance for size or coordinate changes; emotional metaphors, working as a matrix, that allow expression of emotions and emotional states; structural or cognitive metaphors, comparing abstract concepts like love or freedom, and are a mixture of ontological and orientations metaphors. Metaphorical extensions produce changes of the language meaning. But in all cultures metaphors maintain their structural quality, because they produce images that compares two words, perceptions, different things or concepts, have a literal and a figurative meaning and the literal meaning is understandable from the context.

The development of the social-emotional component of personal development

School together with professionals have the power and tools to help students to develop in personal and social terms, by facilitating the sense of value of their potential, capacity for self-reflection, flexibility, creativity, positive attitudes towards themselves and others, and by inducing a positive perception of past experience and future. Personal development activities in primary classes but not only, can optimize the psycho-social functioning of students. For the social-emotional development of students we consider therapeutic stories as an effective method to shape the way they interact with the world and to reveal the essential aspects of themselves. The stories have a universal appeal and their effectiveness as a learning tool has already been demonstrated. The therapeutic stories have a range of functions: describes a series of events, communicates something about us, about our experiences and gives a real insight into the world.

According to Muntean A. (2006) in Romania we have a directive even violent tradition of educating children and about the parental functions. Thus, the author says, they are little known by parents and educators the sensitive issues of interaction with the child.

However, it is currently known due to this conducted research, the strong impact of the first interactions on the social-emotional development of the child. "The responsibility of parents and the educational system (especially the primary education) but also society in general, is to provide the infant with some optimal conditions to stimulate his/her emotional and cognitive development, generating a internalized model about the world functioning, also coherent and moral. This is the basis from which we have to build the society, to have intelligent and creative adults, capable of independent living and effective increasing the next generation, their children. "(Muntean, A., 2006, p. 173).

This work is a continuation of our exploratory research published in November 2015,

Researching the literature we discovered that in Romania and especially in the world, take place very well articulated and focused interventions, aimed to develop the social-emotional dimension of school children, the middle school pupils and high school students. Thus Brănisteanu Rodica (2013) in her doctoral thesis describes the following programs for social-emotional development:

Social-emotional education programs developed in Romania : a) The educational program "Yes, You Can!", b) Educational program: Training of life skills of disadvantaged children, c) Fast Track program - prevention program focus on children with emotional and social disabilities.Emotional and social education programs developed in the world: a) Programs conducted in schools: The PATH Model (Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies), Resolving Conflict Creatively Program (RCCP), Improving Social Awareness, Social Problem Solving Project (ISA / SPSP) Seattle Social Development Project, Yale-New Haven Social Competence Promotion Program, Oakland's Child Development Project

b) Programs for Early Childhood Intervention for emotional and social skills development for children at risk of 4 years. (Social Emotional Intervention for at Risk 4 years old); Preschoool PATHS (Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies) version preschool "Second Step" (also called "prevention of violence"). Head Start / ECAP Curriculum The Incredible Years. Kids Peaceful Conflict Resolution Program.

c) Programs for parents, Intervention for parents and children at risk - The Circle of Security Program (COS). The Seattle Approach.

Therefore we support the need to ensure the continuity of personal development activities at least in the III and IV grades. Currently the national curriculum in Romania provides these activities only for the preparatory classes, I and II grades, fact that interrupts the training and development process of these children and maybe, some students are deprived of a sustainable and healthy social-emotional development.

The objectives and the research hypothesis

Research objectives

O1. Implementing during the personal development classes of an intervention program based on therapeutic stories for II grade pupils.

O2: The social-emotional development of pupils in the II grade, in the following aspects:

O2.1. Developing interaction skills with adults;

O2.2. Developing positive interaction skills with age close children ;

O2.3: Modifying existing relationships in classroom regarding the level of acceptance and with respect for diversity;

O2.4. Increasing the students pro-social manifestations, understood as: applying and obeying rules in interaction with others, disapproval of antisocial behavior, peaceful conflict solving, assuming responsibilities in the classroom, expressing emotions in interaction with others and providing emotional support to colleagues;

O2.5: Changes in the self-concept: self-awareness, self-image, life events and behaviors;

O2.6: Increasing students' emotional self-control;

O2.7. Developing emotional expressiveness.

The research hypothesis

The application within the personal development lessons of an intervention program focused on therapeutic stories, determines the improving of basic social-emotional skills of school children: interaction with adults, interaction with age close children, acceptance and respect for diversity, pro-social behavior, self-concept, emotional self-control and emotional expressiveness.

The subject sample

The formative intervention was conducted in a class of the Secondary School No. 4 of Sibiu. The experimental group consisted of 36 subjects. Children are from urban areas and mostly from families with high socioeconomic status.

The content sample

The content sample consisted of therapeutic stories, exercises and applications designed to help the pupils to process both consciously and unconsciously the messages sent using the stories presented and to change their thoughts, emotions and behavior patterns, in order to adapt optimally to the conditions and circumstances of life. The intervention was carried out over a period of three months in the second semester of the 2015-2016 school year. For the personal development activities carried out in the experimental group, we used the following therapeutic stories:

Methods and research tools

For the ascertaining stage we used a questionnaire to identify the level of social-emotional development. This instrument consists of two dimensions: one aimed the social development of students and another that takes into account the emotional development. For the social dimension the components are: interaction skills with adults, interaction skills with age close children, acceptance and respect for diversity, development of pro-social behavior. The components of the emotional dimensions are: self-concept development, emotional self-control, emotional expressiveness. The questionnaire has 35 items, and for each item, the possible answers are: never, sometimes, always. During both the pretest and the post-test, pupils were asked to circle only an answer for each item according to what they think and feel. Being an ameliorative research with an inter-subject design, the pedagogical experiment was the method used in the intervention stage. This method was complemented by the spontaneous observation of the subjects’ behavior and attitudes.

Research findings

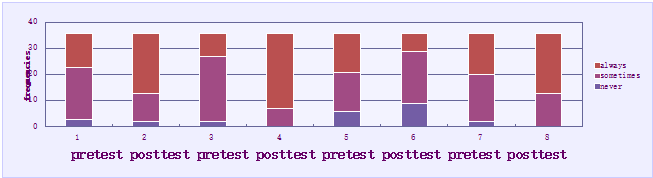

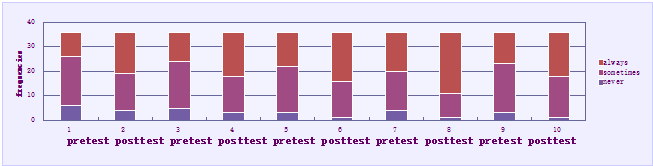

In analyzing the results of the post experimental stage, we started from the premise that those responses that meet more than 50% of choices, constitute a significant change in pupils thinking and behavior and provides insight into how the therapeutic stories managed to develop certain components of the social-emotional side of the personality. Thus, we analyzed and interpreted the first dimension regarding the social development of young schoolchildren. In Figure

So, in the post-test stage we found out that there are significant changes in the interaction skills with adults, regarding following aspects: the ease of communication with adults (63.88%), forms of polite communication (63.88 %%), granting response to adults questions (80.55%) and request for information or support from adults (63.88%). The item that surveyed, to what extent students interrupt adults conversation, we did not obtain significant changes in the post-test stage (25%). Only few of the pupils, 25% said that they were able to listen to adults conversations without interrupting.

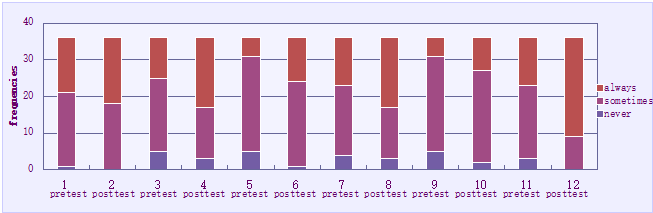

Another aspect studied targeted the interaction skills with children of the same age, illustrated in Fig.

Regarding the interaction skills with children of the same age we found in the post experimental stage, that through the intervention based on therapeutic stories told within the personal development lessons, we developed especially children's ability to propose and initiate games involving more than one child (52.77% selected the response option "always"), and provide the ability to seek children’s help when they need it (52.77% chose the in post-test the answer "always"). Another item with significant changes in post-test was about fairness and compliance in group games (75% of the students chose the answer “always”). There were not sufficiently developed aspects such as, positive and respectful relationship with peers colleagues, the initiative to propose new game variants and to cooperate with colleagues and by sharing objects in the gaming activity.

Another aspect of the social dimension that we measured is referring to accepting and respecting diversity. The results are shown in Figure

We see from the graph that the second graders state in proportion of 58.33% in the post-test phase, that they are more tolerant with children of other ethnic groups, no matter their religion. Another aspect developed through the formative experiment, relates to the rights of other people, children and adults developed in proportion of 63.88%. The results are inconclusive for the item: identify people after exterior, age or gender (41.66%) although we expect the results of this aspect to improve. Probably it is yet difficult for these children in the second grade, to categorize people mainly by age and exterior.

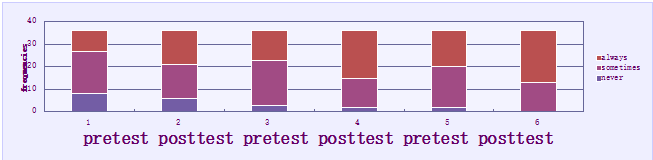

Regarding the pro-social behavior, in the post experimental stage we noticed that the pupils developed mainly the ability to play and work without disturbing their peers (61.11%), to obey simple rules during working hours, breaks and teamwork (72.22%), to apply the rules independent but in similar new situations (50%) and to disapprove the improper behavior (52.77%). We also registered a significant progress in the post-test stage, regarding the acceptance of responsibility and participation in simple decision making (58.33%). The intervention program based on therapeutic stories also developed the pupils’ ability, to offer emotional support to family members or friends, who did not feel well (55, 85%). There were some aspects that we did not develop enough through this experimental program, like using speaking for the conflict solving and then asking adults for help (41.66%) and communicating emotions of joy, sadness or anger (27%). Probably the intervention period was not sufficient, to significantly alter these aspects of the pro-social behavior.

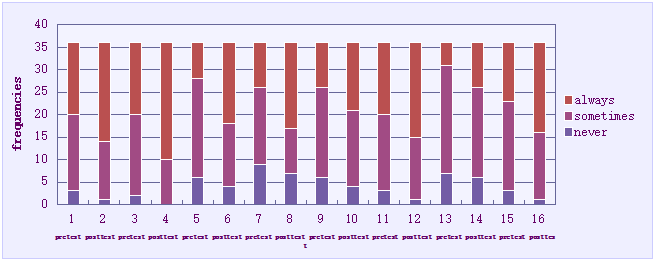

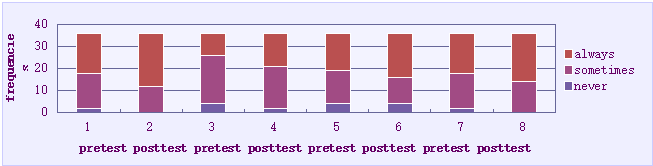

The second dimension of the questionnaire focused on the development of the emotional dimension of the pupils personality. This dimension refers to self-concept, emotional self-control, emotional expressiveness. The obtained results are shown in Figure

The pupils questioned after the experimental intervention based on therapeutic stories, consider in proportion of 50% that they are aware of the environment changing. Then 55.55% of the subjects have a positive self-image as a result of the experiment in which they have been involved and 69.44% of the experimental group children, realize that they have both qualities and flaws. Also 50% of respondents realize that in different situations they have different behaviors. Less developed was the ability to share other information about them-self (47.22%). Results related to emotional self-control reveal that the most aspects of this sub-dimension were significant changed, as we can see from Figure

Another component of the emotional dimension that we measured is the emotional control, the obtained results are presented in Figure

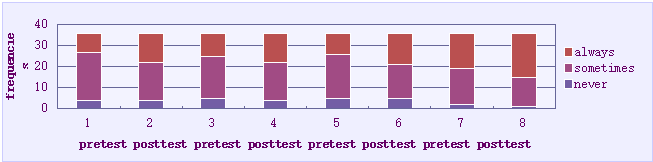

66.66% of the surveyed pupils consider that they wait patiently their turn, while 55.55% say that they can express their feelings without arguing with peers or adults. Another developed aspect is the ability to alter expression and behavior depending on the situation (61.11%). Only 41.66% of the students of the experimental group believe that they control their expression of negative emotions (especially anger). Regarding the development of emotional expressiveness only one aspect of this sub-dimensions was developed significantly through the intervention carried out within the personal development lessons (Figure

Emotional expressiveness is the ability to associate emotions with words and facial expressions and it is considered developed in the post-test stage, by 58,33% of the subjects in the experimental group. The other three aspects of this sub-dimensions were developed in a small extend, the percentage of 50% was not meet, so only 38.88% consider they can express their emotions through art and play, also 38.88% of the students agree that they have appropriate emotional responses to the experienced situations, while 41.66% say when being frustrated they can say and show others what they feel. It seems that emotional expression was during this experimental program the least developed component of the emotional dimension.

Conclusions

We believe that the research objectives were met: 1. Implementing during the personal development classes of an intervention program based on therapeutic stories for pupils' of II class. 2. The social-emotional development of pupils in the II grade, excepting the sub-component emotional expressiveness.

Thus we can say that the research hypothesis has been confirmed, which states that the application within the personal development lessons of an intervention program focused on therapeutic stories, determines the improving of basic social-emotional skills of school children: interaction with adults, interaction with age close children, acceptance and respect for diversity, pro-social behavior, self-concept, emotional self-control and emotional expressiveness.

The limits of the conducted research aimed at the small number of subjects enrolled in the research; the difficulty of working with 36 students on personal development topics; the need for a specialist who should work for a longer period of time with the students, to significantly alter certain aspects of the emotional dimension of the students personality.

References

- Băban, A. (2001). Consiliere educaţională. Editura Psinet. Cluj-Napoca.

- Belmont, J. A. (2015). 103 activităţi de grup. Idei de tratament şi strategii practice. Editura Trei. Bucureşti.

- Brănişteanu, R. (2013). în Rezumat Teză de doctorat Educaţia socio-emoțională– ateliere pentru preşcolari. disponibil on-line la adresa: https://ro.scribd.com/document/246240423/Rezumat-Sulea-Branisteanu-Rodica-1, accesat pe data de 23. 08. 2016

- Burns, G.W. (2011). 101 poveşti vindecătoare pentru copii şi adolescenţi. Folosirea metaforelor în Terapie. Editura Trei. Bucureşti.

- Burns, G.W. (2012). 101 poveşti vindecătoare pentru adulţi. Folosirea metaforelor în Terapie. Editura Trei. Bucureşti.

- Herman, I. R. (2015). The importance of the personal development activities in school. In Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 209. Editor. Elsevier. P. 558-564. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042815056347

- Krüger, & Michalek, (2011). Wollscheid, (2013). in Ţibu S. & Goia, D. (coord.). (2014). Parteneriatul şcoală - familie - comunitate. Editura Universitară. Bucureşti.

- Lakoff, G. & Jonhson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press. Chicago

- Muntean, A. (2006). Psihologia dezvoltării umane. Editura Polirom. Iaşi

- Oevermann, apud Wollscheid, (2013). in Ţibu S. & Goia, D. (coord.). (2014). Parteneriatul şcoală - familie - comunitate. Editura Universitară. Bucureşti.

- Opre, A. (coord). Damian, L. & Ghimbuluţ, O. & Gibă, R. & Macavei, B. & Calbaza-Ormenişan, M. & Rebega, O. & Vaida, S. (2012). Lumea lui SELF. Poveşti pentru dezvoltarea socio-emoţională a copiilor şcolari mici. Editura ASCR. Cluj-Napoca.

- Peivio, (1993). in Dafinoiu, I. (2000). Elemente de psihoterapie integrativă. Editura Polirom. Iaşi.

- Pert, (1995). (1987). & Rossi, (1993). Rossi & Cheek, (1998). in Burns, G.W. (2011). 101 poveşti vindecătoare pentru copii şi adolescenţi. Folosirea metaforelor în Terapie. Editura Trei. Bucureşti.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

22 December 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-017-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

18

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-672

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Ramona, H. I. (2016). The Contribution of Therapeutic Stories to the Social-Emotional Development of Pupils. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development - ERD 2016, vol 18. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 249-260). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.12.33