Abstract

Vast changes in the education field have an effect on teachers’ job satisfaction. In a tightening competition principals of educational institutions have to keep track of their staff’s satisfaction, as it is an important factor in achieving the organization’s objectives. The aim of the current article is to find out about the internal (e.g., work-related collaboration with colleagues and school principals, school management) and external (e.g., salary, promotion) factors influencing job satisfaction. Forty-five primary school teachers from 28 Estonian schools participated in the study. Structured interviews were used to collect teachers’ attitudes and descriptions and thematic analysis to analyze them. It was found that primary school teachers’ job satisfaction was greater in the case of internal factors. It became evident that about 50% of the primary school teachers were satisfied with work-related matters and school management. It appeared that even though the professional development of teachers was supported in small quantities, teachers found opportunities for self-development by exchanging knowledge and experiences with colleagues. Most teachers were not satisfied with their salary and possibilities for promotion in schools. When teachers are satisfied the collegiality, job satisfaction with school environment and job performance improve.

Keywords: Job satisfactioninternal and external factorsprimary school teacher

Theoretical background

Introduction

Job satisfaction has been studied in different areas, including economy, educational policy and psychology (Loogma, Tafel-Viia, & Ümarik, 2013; Tech, & Waheed 2011). In the 1960s and 1970s, when the interest in the job satisfaction and dissatisfaction emerged, Locke (1969) defined these terms in following ways. The job satisfaction refers to “the pleasurable emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job as achieving or facilitating one’s job values”. Vice versa, the job dissatisfaction was defined as “the unpleasable emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job as frustrating or blocking the attainment of one’s values”. The most decisive characteristic of job satisfaction is the extent to which people like or dislike their job (Spector, 1997).

In recent decades in many countries, including Estonia, much attention has been paid to the relationship between different characteristics of teachers, pedagogical framework, work-related factors, and job satisfaction. The studies have indicated positive relations between employees’ professional performance and job satisfaction (Saiti, 2007; Weiss, 2002). It has been found the external factors may prevent employees’ dissatisfaction with job more effectively, but they do not lead directly to the job satisfaction (Tech, & Waheed 2011; Wei-Cheng et al., 2008). In school context it has been found that the students gain better academic results if their teachers’ job satisfaction is higher (Jacob, 2012; Loogma et al., 2014; OECD, 2014). Although, as the primary school teacher is a teacher in the most numerous types in Estonia (OECD, 2014), the research at these job satisfaction is still limited. Also, the evidence about the effect of different internal and external factors (professional development, collaboration with colleagues, school management, salary etc.) on teachers’ job satisfaction is not sufficient (Ghavifekr, & Pillai, 2016; Leithwood, 2006). Thus, the aim of the current study is to determine internal and external factors affecting the Estonian primary school teachers’ job satisfaction.

Internal and external factors of job satisfaction

Job satisfaction is related to organization’s productivity and efficiency (Koustelios, 2001), employees’ loyalty (Matzler, & Renzl, 2006) and creativity (Gaki et al., 2013) as well as school performance (Caprara et al., 2006; Saiti, 2007). Some theorists have specified the job satisfaction as a multifaceted construct which includes different components. Broadly, the components may be divided into two groups: internal (or

The job satisfaction of teachers is an important factor of the organization’s success and it has an impact on the quality of teaching provided in the classroom (Hamre, & Pianta, 2010; Tech, & Waheed, 2011). Skaalvik & Skaalvik (2011) have conceptualised job satisfaction as a reaction what influences teacher’s work or role. Although, teachers’ satisfaction with school managers and principals is not sole indicator of management efficiency, it is important for effective environment where management decisions are being made (Hung, 2012). Thus, Sharma & Jyoti (2006) have found that every aspect of the job (e.g., colleagues’ behavior, promotion and recognition, students’ achievement, emotional and physical environment) may perform an essential part in teachers’ satisfaction with their job. Wisniewski & Gargiolu (1997) have stated that teachers’ job satisfaction also associates with freedom to do their work as they want, including teaching favorite subjects, a reasonable class size and support of colleagues. Cooperation with colleagues allows to exchange experiences and to analyze each other’s work as well as to find possible solutions and preventive actions for complex situations (Uibu, Kaseorg, & Kink, 2016). The characteristics of very good teacher are good communication and cooperation skills, good understanding of the substance as well as the ability to convey (Õpetajaameti kuvand ja atraktiivsus, 2016).

According to Herzberg et al. (1959) it is easier to measure external factors, since it is easier to control and manipulate them. In contrast, the internal factors are more subjective and elusive, for investigation of the respondents’ proper descriptions are needed (Braun, & Clarke, 2006).

Context of this study

Estonia has launched significant initiatives to improve the quality of the education system and looking to international standards and best practices (Santiago, Levitas, & Shewbridge, 2016). Estonian teachers’ professional development is supported by contemporary standards and competency-based training system (Kallas, & Tatar, 2015; OECD, 2014). In 2005, the standards of teachers’ professional work were described in terms of competencies (Õpetaja V kutsestandard, 2005). In this document, teachers’ professional career was described at competency-based structure: beginning from the knowledge and finishing with different competencies. In 2013, the three-level standard of teachers’ competencies was approved by The Ministry of Education and Research (Estonian Qualifications Authority, 2013). Currently, teachers’ professional activities and competencies are described in detail according to their work experience (teacher, competent teacher, master teacher). In addition to common roles and responsibilities, more experienced teachers had a chance to perform different additional tasks. They have the possibility to practice as a teacher-researcher or teacher-trainer in pre- and in-service teaching, to supervise students during their pedagogical practice at school and consult supervisors from the university (Eisenschmidt, & Koit, 2014). Such innovation has probably had a positive effect on Estonian teachers’ job satisfaction. In recent studies (Juurmann, 2010; Ülbius et al., 2014) it was indicated that the majority of Estonian teachers (even 90% by Ülbius et al., ibid.) are satisfied with school microclimate and with the recognition and feedback received from their colleagues.

However, the studies, conducted in Estonia, have indicated that working conditions, school contexts, and organizational culture still do not sufficiently support teachers’ professional development (Eisenschmidt, 2011; Toomela, 2009). The schools in Estonia do not seem to be using the competency-based career structure as a possibility to distribute roles and tasks among teachers within schools (Santiago, Levitas, & Shewbridge, 2016). Hence, the career structure is yet to penetrate schools’ teacher management practices. Therefore, the current study focuses on teachers’ job satisfaction, which may, among other things, have an impact on Estonian school culture and educational system.

Research questions and purpose of the study

Drawing on previous studies (Juurmann, 2010; Saiti 2007; Santiago et al., 2016; Sharma, & Jyoti, 2006; Toomela, 2009) we stated the following research questions:

This study aimed to determine the internal and external factors affecting Estonian primary school teachers’ job satisfaction.

Research methods

Participants

Within the framework of the study, 45 primary school teachers from 28 Estonian schools were interviewed. All teachers taught basic subjects from Grades 1 to 3. The teachers’ average age was 41.2 years; the youngest was 26 and the oldest 58 years. Their teaching experience varied from one year to 39 years (M = 18.3).

Data collection and analysis

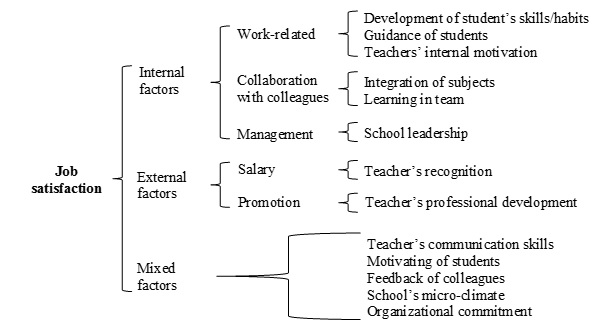

Structured interviews were conducted with the sampled primary school teachers. The interviews consisted of 15 main questions. Using targeted thematic analysis (Braun, & Clarke, 2006), the job satisfaction components were classified into groups based on the conception of Herzberg et al. (1959). For the thematic analysis the interviews were fully transcribed. Then, the main themes, sentences or sets of sentences that expressed a conceptual whole, were implemented as analytic units. Based on analysis, three thematic dimensions of job satisfaction, which expressed work conditions, collaboration with colleagues, school management, salary etc., were differentiated. These themes were differentiated into three groups: 1) internal factors, 2) external factors and 3) mixed factors (see Fig.

Findings and discussion

According to the results, two obvious thematic blocks – internal and external factors – were differentiated. Additionally, components belonging into both groups also occurred in primary school teachers’ descriptions. This group was named a

Internal factors group

In teachers’ answers we distinguished several

Teachers also described how they arranged an adequate learning environment for their students. It corresponds to the expectations of the whole society, that

Although Herzberg et al. (1959) have stated that motivation is like an internal self-charging battery, it is also important to receive external influences to keep higher motivation. In our study, only 26 teachers of 45 described different components of

“I think, me, as a teacher, I have to give something. This is perhaps a more practical value. I think, I can explain complicated things in the simplest way very well.” (T2)

In line with Juurmann’s (2010) study, one teacher of our study mentioned that if school principals take their opinions more into account and the students are also motivated, the teachers’ internal motivation will increase.

The next dimension, what was distinguished in teachers’ interviews was

“We exchange work programs with other primary school teachers. In that sense, our work plans are a joint project.” (T3)

Teachers also evaluated the cooperation with their students highly. “

However, the sub-theme

Also, the

External factors group

Next, we analyzed external factors influencing a job satisfaction of primary school teachers.

“In spring, we will select the best teacher and the best colleague, and in autumn (on day of teachers) we are recognized. The school principals indicate that they care about us.” (T6)

In line with previous study (Juurmann, 2010), the primary school teachers of our study described also the main ways of recognition in their schools: different certificates, verbal laudation, various work accessories at the beginning of the school year (e.g., pens, notebooks, etc.). On the other hand, some teachers mentioned they were waiting for a greater recognition by their school principals. For example,

“I don’t know. It puts a strain on us, it does not motivate.” (T7)

“I have worked for10 years and I have got only flowers at the beginning of a school year.” (T4)

Also, in the TALIS 2013 survey it was found that the recognition is quite a rare phenomenon in Estonian schools; principals do not encourage their teachers enough (Ülbius et al., 2014). Teachers are often under pressure to do more and to obtain high outcomes in their professional job, but the resources for these activities are insufficient (Bentea, & Anghelache, 2012). Another reason may be low salary. Insufficient payment for particular demands may influence teachers’ level of job satisfaction (Sharma, & Jyoti, 2006). Tech & Waheed (2011) have emphasized that a subjective level of salary satisfaction is an important factor of job satisfaction. The dissatisfaction with salary not necessarily implies a lack of job satisfaction, or vice versa. For example, if a teacher has no career opportunities in school, it does not mean he or she is not satisfied with their job. However, if the salary is not sufficient, it usually causes dissatisfaction with job. If the salary increases, the dissatisfaction can be lost, but it does not guarantee higher satisfaction with their job.

The second external factor, which emerged in our study, was

Mixed factors group

Several sub-themes, which were placed into

The second sub-theme, which was located to the mixed factors group, was the

“The teacher must take into account their students’ peculiarities and create the conditions for learning, which allows recognizing the instruction as an attractive, interesting and age-appropriate process.” (T9)

“I feel that I have to obtrude the recognition to my students. I think, we also have to say “Thank you!” to students.” (T4)

In contrast to Juurmann (2010), who indicated that about one-third of teachers were satisfied with feedback received from colleagues, we found that only three teachers highlighted the importance of

The next important sub-theme, indicated in teachers’ interviews, was the

The success of organization depends on decisions and behavior of each member (Mumford, 1992). As previous studies have shown, the job satisfaction is strongly related to the

“I have worked here for 40 years, this is my school. All my relatives – my grandfathers, my great-grandfathers and grandparent’s had studied there back to the sixth generation. One of my great-grandfathers had worked in this school as a bookbinder. I know the homes of all students I am teaching. It helps me to contribute a lot when I know how to approach my students.” (T11)

Organizational commitment supposes that all members wish to be active players in this organization; they feel that they have high status in organization, and are willing to contribute beyond what is expected of them (Bogler, & Somech, 2004). Hulpia & Devos (2010) found that teachers generally commit to schools; they are proud of their schools and are willing to exert themselves for the school. In line with these results, the majority of Estonian primary school teachers were satisfied with their job.

Limitations and conclusion

Our study had some limitations. First, data collection through structured interviews does not ensure complete anonymity of the interviewees and it might affect teachers’ responses. However, the interviewer did not know the teachers previously and they met before the interviews, for the purpose of this study. Second, teachers’ personal characteristics and factors related to the school environment were not observed in this paper. Third, alternative measurement techniques can be used for data collection.

Despite these limitations, several strengths of this study should be highlighted. Although TALIS 2013 survey (Ülbius et al., 2014) showed that 90% of Estonian teachers are generally satisfied with their job, our study indicated several internal and external and mixed factors influencing the primary school teachers’ job satisfaction. While Herzberg et al. (1959) found that employees are more motivated by internal than by external factors, our study showed that various factors might influence teachers’ satisfaction differently. Primary school teachers were not satisfied with the growth of work responsibilities, low salary and how they are recognized in schools. Teachers’ overall satisfaction, however, depends on particular conditions and frame in the specific school. This must be kept in mind when concluding the results of the current study.

References

- Bentea, C.-C., & Anghelache, V. (2012). Teachers’ perceptions and attitudes towards professional activity. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 51, 167–171. DOI:

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77−101.

- Bogler, R., & Somech, A. (2004). Influence of teacher empowerment on teachers' organizational commitment, professional commitment and organizational citizenship behaviour in schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20, 277–289. DOI:

- Caprara, V., Barbaranelli, V., Steca, P., & Malone, P. (2006). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of job satisfaction and students’ academic achievement: a study at the school level. Journal of School Psychology, 44(6), 473-490. DOI:

- Chang, R. Y. (1994). Success through teamwork: A practical guide to international team dynamics. Irvine, CA: Chang Associates.

- Dee, J. R., Henkin, A. B., & Singleton, C. A. (2006). Organizational commitment of teachers in urban schools: examining the effects of team structures. Urban Education, 41, 603–627. DOI:

- Dinham, S., & Scott, C. (2000). Moving into the third, outer domain of teacher satisfaction. Journal of Educational Administration, 38(4), 379–396. DOI:

- Eisenschmidt, E. (2011). Teacher education in Estonia. In M. Valenčič Zuljan & J. Vogrinc (Eds.), European dimensions of teacher education – Similarities and differences (pp. 115−132). Ljubljana: University of Ljubljana.

- Eisenschmidt, E., & Koit, R. (koost.) (2014). Kutsestandardi rakendamine õpetajaks kujunemisel ja edasises professionaalses arengus. Tallinn: Innove.

- Estonian Qualifications Authority. (2013). Professional standard: Teacher EstQF level 7. Retrieved from http://www.kutsekoda.ee/en/kutsesysteem/tutvustus/kutsestandardid_eng

- Gaki, E. R., Kontodimopoulos, N., & Niakas, D. (2013). Investigating demographic, work-related and job satisfaction variables as predictors of motivation in Greek nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 21, 483490. DOI:

- Ghavifekr, S., & Pillai, N. S. (2016). The relationship between school’s organizational climate and teacher’s job satisfaction: Malaysian experience. Asia Pacific Education Review, 17(1), 87106. http://link.springer.com/article/

- Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2010). Classroom environments and developmental processes. Handbook of Research on Schools, Schooling, and Human development, 25–41. Retrieved from https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/

- Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., & Snyderman, B. (1959). The motivation to work. New York: Wiley.

- Hulpia, H., Devos, G., & Rosseel, Y. (2009). The relationship between the perception of distributed leadership in secondary schools and teachers’ and teacher leaders’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 20(3), 291–317. DOI:

- Hung, C.-L. (2012). Internal marketing, teacher job satisfaction, and effectiveness of Central Taiwan primary schools. Social Behavior and Personality, 40(9), 14351450. DOI:

- Jacob, A. (2012). Examining the relationship between student achievement and observable teacher characteristics: Implications for school leaders. International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation, 7(3), 1–13.

- Juurman, E. (2010). Tartu munitsipaalüldhariduskoolide pedagoogide küsitlus. Tartu: Tartu Linnavalitsuse haridusosakond. Retrieved from http://info.raad.tartu.ee/uurimused.nsf/web1?OpenView&ExpandView

- Kallas, K., & Tatar, M. (toim). (2015). Uuring „Õpetajate täiendusõppe vajadused”. Lõpparuanne. Balti Uuringute Instituut. Retrieved from https://www.ibs.ee/wp-content/uploads/%C3%95petajate-t%C3%A4iendus%C3%B5ppe-vajadused-uuringuaruanne.pdf

- Koustelios, A. D. (2001). Personal characteristics and job satisfaction of Greek teachers. The International Journal of Educational Management, 15(7), 354538. DOI:

- Leithwood, K. (2006). Teacher working conditions that matter: Evidence for change. Toronto: Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario. Retrieved from http://www.etfo.ca/Resources/ForTeachers/Documents/Teacher%20Working%20Conditions%20That%20Matter%20-%20Evidence%20for%20Change.pdf

- Locke, E. A. (1968). What is job satisfaction? Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED023138.pdf.

- Loogma, K., Tafel-Viia, K., & Ümarik, M. (2013). Conceptualising educational changes: A social innovation approach. Journal of Educational Change, 14(3), 283–301.

- Matzler, K., & Renzl, B. (2006). The relationship between interpersonal trust, employee satisfaction, and employee loyalty. Total Quality Management, 10, 12611271. DOI:

- Mumford, A. (1992). Individual and organizational learning: The pursuit of change. Management Decision, 30(6). DOI:

- OECD [The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development] (2014). TALIS 2013 Results. An international perspective on teaching and learning. Retrieved from DOI:

- Õpetaja V kutsestandard. (2005). [Teacher’s Professional Standard V]. Retrieved from http://www.hm.ee/index.php?044930.

- Programm “Pädevad ja motiveeritud õpetajad ning haridusasutuste juhid 20162019”. Tartu: Haridus- ja Teadusministeerium. Retrieved from https://www.hm.ee/sites/default/files/lisa_1_programm_padevad_ja_motiveeritud_opetajad_ning_haridusasutuste_juhid_2016.pdf

- Saiti, A. (2007). Main factors of job satisfaction among primary school educators: factor analysis of the Greek reality. Management in Education, 21(2), 2832. http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ803561

- Salumaa, T. (2007). Representatsioonid organisatsioonikultuuridest Eesti kooli pedagoogidel muutuste protsessis. Doktoritöö. Tallinn: Tallinna Ülikool.

- Santiago, P., Levitas, A., Radó, P., & Shewbridge, C. (2016). OECD reviews of school resources: Estonia 2016. OECD Reviews of School Resources, OECD Publishing, Paris. Retrieved from DOI: 10.1787/9789264251731-en

- Santisi, G., Magnano, P., Hichy, Z., & Ramaci, A. (2014). Metacognitive strategies and work motivation in teachers: An empirical study. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 12271231. DOI:

- Schratz, M. (2014). The European teacher: Transnational perspectives in teacher education policy and practice. CEPS Journal, 4(4), 1127. Retrieved from http://www.pedocs.de/volltexte/2015/10057/pdf/cepsj_2014_4_Schratz_European_teacher.pdf

- Sharma, R. D., & Jyoti, J. (2006). Job satisfaction among school teachers. IIMB Management Review, 18(4), 349363.

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2011). Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 10291038. DOI:

- Spector, P. (1997). Job satisfaction: Application, assessments, causes and consequences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Tech, T., & Waheed A. (2011). Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory and job satisfaction in the Malaysian retail sector: The mediating effect of love of money. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 16(1), 33–51.

- Terek, E., Glušac, D., Nikolic, M., Tasic, I., & Gligorovic, B. (2015). The Impact of Leadership on the Communication Satisfaction of Primary School Teachers in Serbia. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 15(1), 7384. DOI:

- Torokoff, M., & Mets, T. (2008). Organisational learning: A concept for improving teachers’ competences in the Estonian School. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 5(1), 6482. DOI:

- Toomela, A. (2009). Projekt “Eesti põhikooli efektiivsus”. Lõpparuanne. Retrieved from http://dspace.ut.ee/bitstream/handle/10062/40918/Uld_Efektiivsus.pdf

- Uibu, K., Kaseorg, M., & Kink, T. (2016). Perceptions of primary school teachers on the disciplines related to the learning of organisation leadership. Estonian Journal of Education, 4(1), 5891. DOI:

- Õpetajaameti kuvand ja atraktiivsus. (2016). Tallinn: TNS Emor.

- Ülbius, Ü., Kall, K., Loogma, K., & Ümarik, M. (2014). Rahvusvaheline vaade õpetamisele ja õppimisele: OECD rahvusvahelise õpetamise ja õppimise uuring TALIS 2013 tulemused. Tallinn: SA Innove. Retrieved from https://www.hm.ee/sites/default/files/talis2013_eesti_raport.pdf

- Wei-Cheng J. M., Ellsworth, R., & Hawley, D. (2008). Job satisfaction and career persistence of beginning teachers, International Journal of Educational Management, 22(1), 4861. DOI:

- Weiss, H. M. (2002). Deconstructing job satisfaction. Separating evaluations, beliefs and affective experiences. Human Resource Management Review, 12(2), 173194.

- Weiqi, C. (2007). The structure of secondary school teacher job satisfaction and its relationship with attrition and work enthusiasm. Chinese Education and Society, 40(5), 1731. http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ787846

- Wisniewski, L., & Gargiulo, R. (1997). Occupational stress and burnout among special educators: A review of the literature. The Journal of Special Education, 31, 325346.

- Witherspoon, P. D. (1997). Communicating leadership – An organizational perspective. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

22 November 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-015-0

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

16

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-919

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Kaseorg, M., & Uibu, K. (2016). Factors Influencing Job Satisfaction of Estonian Primary School Teachers. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2016: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 16. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 73-83). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.11.9