Abstract

The paper describes the results of a research study, which examined the degree of addiction in 18-year-old grammar school students in the Czech Republic to computer games. In the research the authors used a quantitative research approach based on the author’s own questionnaire to identify the degree of addictive behaviour in students in relation to computer games. The research sample consisted of 525 students in grade three of four-year grammar schools (or an equivalent grade of multi-year grammar schools) from 10 randomly selected schools. The author used a statistical analysis to identify the groups of 18-year-old students according to their addictive behaviour. In the research the following result processing methods were used: K-means cluster analysis, globalized cluster analysis, Student’s t-test and analysis of variance ANOVA; the analysis of nominal data was performed by means of the Chi-square test of independence. The research study suggested that 7.8 % of all grammar school students involved in the study showed addictive behaviour in relation to computer games. Their behaviour was affected by gender; male students showed a significantly higher degree of addictive behaviour compared with female students. An interesting finding is the effect of the school’s focus on addictive behaviour. In a Church grammar school the degree of addictive behaviour was significantly lower than in other types of schools. The results of the research study also suggested three basic groups of grammar school students according to their approach to computer games. In addition to other aspects, these groups showed a completely different degree of addiction.

Keywords: Grammar school studentscomputer game addictiontypologyglobalized cluster analysis

Introduction

In today’s information-based society, the way of using digital technologies in everyday lives of its citizens is changing, and so is the role of these technologies in education. It is clear, however, that the use of these technologies varies by specific groups of users, sometimes we even speak of a digital divide (digital gap) between generations (Van Dijk). Excessive use of digital technologies can lead to various forms of addiction (APA, 2013); therefore, especially in school-based education, these risks should be highlighted, identified and appropriate measures should be taken. During this stage of development, students are most threatened by addiction to mobile phones, social networks and computer games.

A large proportion of especially young people cannot imagine their life without information and communication technologies. They feel that if they did not use the Internet and were not on-line all the time, they would be at risk of social exclusion (Zounek et al., 2016). Information and communication technologies also frequently represent a source of entertainment and education (Dostál, 2009; Stoffová, 2016). From an early age, children play on the computer, tablet or mobile phone, and this innocent play may gradually change into a form of addiction (Kopecký, 2013).

Problem statement - Computer Game Addiction

In today’s information-based society, computer games are widely spread (Entertainment Software Association, 2015), but at the same time highly criticized – particularly in terms of possible addictions (Nešpor, 2011). Today, most children from about 3 to 4 years of age own at least one technical gaming gadget, for example a mobile phone, tablet or computer. According to a research study conducted in the Czech Republic (Basler, 2016) as many as 96.1 % of elementary school students sometimes play computer games, and therefore, it makes sense to address the risks associated with computer games and especially computer game addition.

According to the APA (2013), clinical computer game addition means that an individual meets five or more of the following symptoms in the course of a single year:

•Pre-occupation (thinking about previous or next playing computer games becomes a dominant activity in life).

•Withdrawal symptoms when gaming is inaccessible (typical symptoms include irritation, anxiety, stress or sadness, but there are no physical addiction symptoms).

•Tolerance; an individual requires an increased amount of time for playing.

•Repeated unsuccessful effort to control or stop playing computer games.

•Loss of previous interests and hobbies, free time is devoted to computer games.

•Continued playing computer games despite knowing the related psychosocial problems.

•Deceiving the surroundings (family, friends) about the extent of playing computer games.

•Playing computer games is a means of escaping from problems or relieving negative moods (feelings of helplessness, guilt, anxiety or depression).

•Risk or loss of close relationships, job, education or career opportunities as a result of playing computer games.

Research questions

The basic research question formulated in the framework of the present research study asks about the degree of addictive behaviour in secondary (grammar) school students in relation to computer games. The next question focuses on whether there are typical groups of 18-year-old grammar school students by their attitude to computer games and by their degree of addictive behaviour.

At this stage of research, the group of grammar school students was selected because in the Czech Republic grammar schools are attended by students, most of whom want to continue study at universities. Therefore, the authors assumed that grammar school students would show a lower degree of gaming and related addictive behaviour compared with students from other types of secondary schools.

Purpose of the study

The objective of the research study was to determine the degree of addictive behaviour in relation to playing computer games in Czech 18-year-old grammar school students.

Another objective of the research was, based on an analysis of responses of grammar school students, to hypothetically divide these students into characteristic groups according to the degree of their addictive behaviour in relation to playing computer games. On the basis of theoretical knowledge, however, it was impossible to determine how many groups of students should be identified. Preliminary results of the research (Chráska jr, 2016) suggested two groups according to the students’ responses. Therefore, it was decided to determine the number of typical groups of students according to the Generalized Cluster Analysis, which can positively quantify the number of groups in the research sample.

Research methods

For the purposes of the research the authors used a yet non-standardized questionnaire (Chráska sr, 2007), which was based on a questionnaire used in 2015 (Basler, 2016). For the purposes of an IGA project aimed at the issue of student addiction to computer games in a wider context, in 2016 new items were added to the questionnaire. The purpose of the questions was to determine detailed characteristics of the types of students according to their addition to computer games Apart from these characteristics, the questionnaire focused on the degree of addictive behaviour in relation to playing computer games by means of 11 statements. The degree of agreement with each statement was indicated by the students on a six point scale with coded answers: totally agree (value 6), agree (5), rather agree (4), rather disagree (3) disagree (2) completely disagree (1). Regarding the extent of the paper, Table

Description of the research sample

The research study was carried out in 10 randomly selected grammar schools in the Czech Republic in the Olomouc Region, Pardubice Region, Moravian-Silesian Region and Zlín Region in May 2016. The overall research sample consisted of 525 students in grade three of four-year grammar schools (or an equivalent grade of multi-year grammar schools). The structure of the respondents is specified in Table

Findings

Identification of addictive behaviour in students in relation to playing computer games

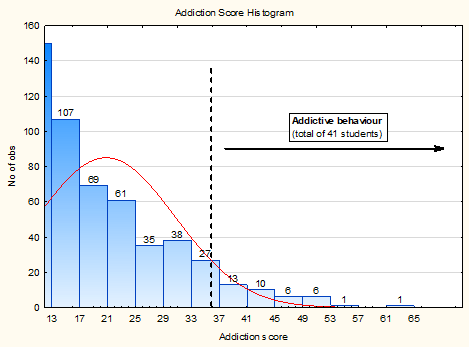

Based on the students’ responses to twelve questionnaire items (Q5, Q10, Q11, Q12, Q13, Q15, Q16, Q17, Q18, Q19, Q20, Q21 – see Tab.

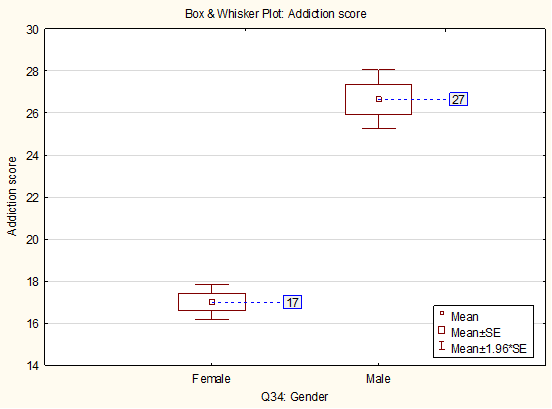

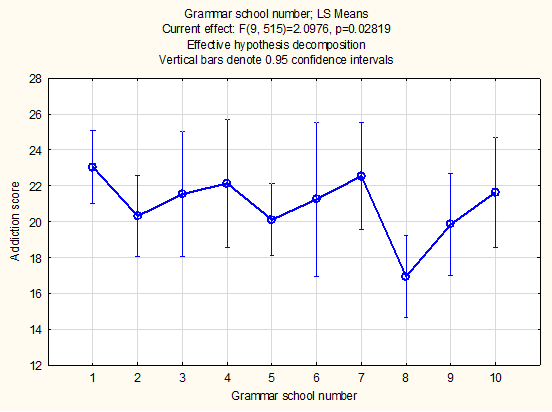

The authors were also interested whether the students’ addictive behaviour in relation to playing computer games varied by gender and schools. A comparison – see Figures

Identification of typical groups of students according to their attitude to computer games

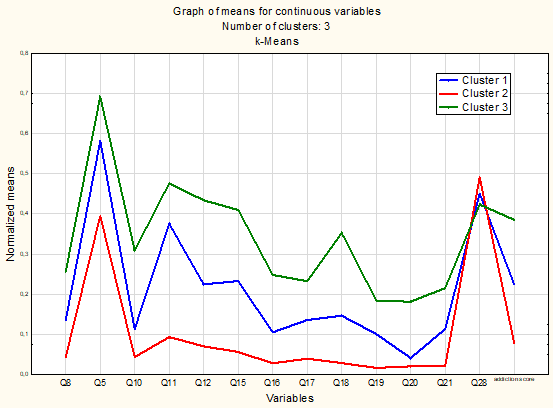

The authors performed a Generalized Cluster Analysis of the students’ responses for continuous and nominal variables. In the first step of the STATISTICA 12 programme using the “Validation” procedure in the Generalized Cluster Analysis the authors determined the probable number of clusters, which was the anticipated 3 clusters – see table

The results the Generalized Cluster Analysis are presented in Table

Table

The results of the research study suggested three groups (clusters) of 18-year-old grammar school students according to their approach to computer games. These groups also showed a completely different degree of computer game addition.

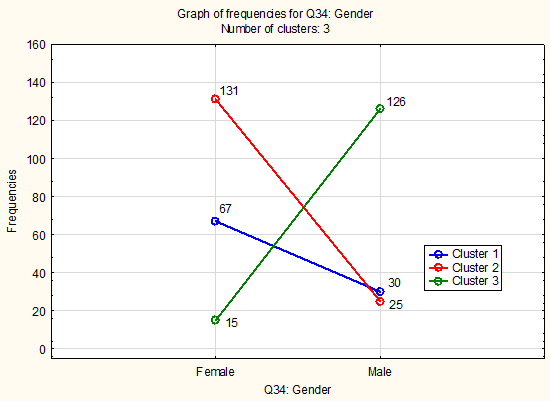

Cluster 1 includes students who often play PC games including on-line games, their parents often set limits for playing computer games, and as a result of playing they stay up late (but only once a month). They often play computer games at school during lessons (e.g. using a mobile phone), and sometimes on Facebook. The group is slightly dominated by female students. The students play PC games for 81 minutes on average, in their free time they do sports. The students in this group show a lower addictive behaviour score (average score 23) and comprise about 25 % of all students.

Cluster 2 includes students with the lowest addictive behaviour score (average score 15), they play PC games for only 26 minutes a day games on average, they do not play on-line games, in their free time they go out with friends. More often they play educative computer games; they started playing at about 9.5 years of age. This group is significantly dominated by female students and comprises about 39 % of all students.

Cluster 3 includes students with the highest addictive behaviour score (average score 32), they play PC games for approximately 2.5 hours a day, mostly on-line, in their free time they again play computer games. As a result of playing games, the students also stay up late (typically once a week and once a month). When they do not play, they are more stressed than the students in groups 1 and 2. For them, PC games are the most powerful tool for relaxation, they often play PC games even if they have school assignments (e.g. preparation for a test), and frequently they cannot imagine their life without PC games. This group is significantly dominated by male students; they have played computer games since about 8 years of age; the group comprises about 36 % of all students.

Conclusions

The research study suggested that 7.8 % of all grammar school students showed addictive behaviour in relation to playing computer games. The prevalence of addictive behaviour varied by gender and accounted for 16.26 % in male students and only 2.38 % in female students.

It was also shown that the average degree of addictive behaviour significantly differed between male students (approximate score 27) and female students (score 17). Another influence is the specific school attended. It was revealed that students from a Church grammar school showed a significantly lower degree of addictive behaviour compared with other schools.

A total of three distinct groups of grammar school students were identified according to their attitude to computer games. In this context, the most problematic is the third group, which shows the highest degree of addictive behaviour and the highest playing time (in total the group comprised about 36 % of students). These students could be subject to a strong negative influence by computer games and their addictive behaviour could intensify over time. This was also evidenced by the responses of the students in this group to the question of what they would do if they could not play for six months: “I would kill myself.” “I think I would break down and I would have to undergo PC addiction treatment – I do not play often, but it is very important to me.” “I would play on my mobile phone.” “I would die.” “I would play on PS 4.” “I will go and play on my friend’s console.”

However, the students in the first group were also likely to experience certain problems; they did not play that often but had a tendency to play during lessons, they did not concentrate and disturbed (the group comprised about 25 % of the students).

Only the second group of students was relatively trouble-free; the group comprised 39 % of all students. But even the students in this group played games for 26 minutes a day on average.

In the next stage of the research, which will take place in November 2016, the authors will aim at the situation in other types of secondary schools, where students, regarding the practical focus of the schools, might have completely different tendencies. The authors assume that the potential risk group of students with a higher degree of addictive behaviour might be larger in these schools. All things considered, the 7.8 % of grammar school students who showed signs of addictive behaviour was a relatively high number, given that these students prepared for further study at university.

Acknowledgements

The paper was supported by project IGA_PdF_2016_028 “Identification of risks of social networks and computer games for children depending on their preferred use of information and communication technologies”.

References

- APA. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed. Washington, D.C., American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Basler, J. (2016). Počítačové hry a způsob jejich využívání u žáků základních škol. Trendy ve vzdělávání, 9(1), 10-19.

- Chráska, M. jun. (2008). Uplatnění vícerozměrných statistických metod v pedagogickém výzkumu. Olomouc, Votobia.

- Chráska, M. jun. (2016). Žáci gymnázia a míra jejich závislosti na počítačových hrách. Trendy ve vzdělávání, 9(1), 110-114.

- Chráska, M. sen. (2007). Metody pedagogického výzkumu: Základy kvantitativního výzkumu. Praha, Grada.

- Dostál, J. (2009). Výukový software a didaktické počítačové hry - nástroje moderního vzdělávání. Journal of Technology and Information Education. 1(1), 24-28.

- Entertainment Software Association. (2015). Essential facts about the computer and video game industry [online], [cit. 2016-07-30], Available from: http://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/ESA-Essential-Facts-2015.pdf

- ISFE, IPSOS MEDIACT. (2012). Videogames in Europe: Consumer study, [online], [cit. 2016-07-30], Available from: http://www.isfe.eu/sites/isfe.eu/files/attachments/euro_summary_-_isfe_consumer_study.pdf

- Kopecký, K. (2013). Rizikové chování studentů Pedagogické fakulty Univerzity Palackého v prostředí internetu, Olomouc, Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci.

- Nešpor, K. (2011). Jak přežít počítač. Kralice na Hané, Computer Media.

- Nešpor, K. & Csémy L. (2007). Zdravotní rizika počítačových her a videoher. Národní registr výzkumů o dětech a mládeži, [online], No. 5, pp. 246–250 [cit. 2014-04-20]. Available from: http://www.vyzkum-mladez.cz/cs/registr/vyzkumy/349-zdravotni-rizika-pocitacovych-her-a-vide.html

- StatSoft, Inc. (2013). STATISTICA (data analysis software system), version 12, www.statsoft.com.

- Stoffová, V. (2016). Počítačové hry a ich klasifikácia. Trendy ve vzdělávání, 9(1), 243-252.

- Van Dijk, J. (2005). The Deepening Divide: Inequality in the Information Society. London, SAGE Publications.

- Zounek, J. & Juhaňák, L. & Staudková, H. & Poláček, J. (2016). E-learning. Učení (se) s digitálními technologiemi. Praha, Wolters Kluwer ČR, a. s.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

18 December 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-015-0

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

16

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-919

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Chráska, M. (2019). Computer Games – Preferred Way of Using ICT by Grammar School Students. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2016: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 16. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 606-616). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.11.63