Abstract

Social skills are considered one of the important factors in the success or failure of every individual in a society. Lack of research in this field along with its considerable significance motivated the present study. The present study presents a comparison of the social skills of students in ordinary schools and talented schools. The required data were collected using a standard questionnaire of students’ social skills assessment. The statistical sample of the present investigation comprised female high school students in the province of Alborz, in which 200 students were selected from eight ordinary schools and 8 exceptional talent schools through cluster sampling. The results showed that the students of talented schools are significantly higher in appropriate social skills and are overconfident, but no significant difference was observed in other components. Teaching the appropriate social skills and providing opportunities and experiences that increase social interactions allows students to practice and apply social strategies and skills in all environments and situations in life.

Keywords: Social skillsintellectstudentsordinary schoolsexceptional talent schools

Introduction

Well-informed teachers of young children recognize the importance of children’s social development. The development of social skills lays a critical foundation for later academic achievement as well as work-related skills (Lynch & Simpson, 2010). Social skills are a collection of learned behaviors giving the individual the ability to have an influential relationship with others and to abstain from socially unreasonable reactions (Agran, Hughes, Thoma, & Scott, 2016; Davies, Cooper, Kettler & Elliott, 2015; Gresham, 2016; Yoder, 2015). Cooperation, collaborating with the others, helping, initiating a relationship, requesting help, and praising and appreciating others are some examples of this type of behavior. Learning the above behaviors and creating influential relationships with others is most important in childhood. Unfortunately, some children do not learn these skills, which is why most of these children encounter negative reactions from adults and other children.

Social skills are behaviors enabling individuals to interact influentially and to abstain from undesirable responses. They represent the individuals’ social and behavioral health success (Rawles, 2016). These skills have their roots in cultural and social foundations and include behaviors such as pioneering in the establishment of new communications, requesting help, and making suggestions to help others. One of the most important educational aims of childhood is to develop social skills, and the level of children’s and adults’ enjoyment of these skills is influential in their personal and social health and their educational success (Morgan, Hsiao, Dobbins, Brown., & Lyons, 2015; Rawles, 2016).

Many children who have not acquired appropriate social skills develop psychological problems such as unsuccessful communication with peers, inappropriate educational performance, not participating in side activities and isolation, rejection by peers, anxiety, depression, and anger in childhood and throughout life (Anastasi, 1990).

Slaby and Gaura (2003) proposed that social skills correspond to social compatibility. In their view, social skills consist of the ability to create interactions with others in a social background that are acceptable and valuable per societal norms. Strayer (1989) suggested that social skills involve mutual compatibility between a child and the social environment and in relation to peers. In this model, compatibility refers to the child’s ability and capacity to predict, absorb, and react to the signs available in a social context. These signs include emotional states or peers’ behaviors. The child’s emotional and social growth involves this process and specifies the child’s or teenager’s ability to select the appropriate behavior and evaluate the social relationships and group structure as well as the level of skill and social ability. Slawmouski and Dann (1996) proposed that social knowledge and skill are the process that enables children and teenagers to perceive and predict others’ behaviors, control their behaviors, and set their social interactions. One of the new theories in social knowledge that investigates social skills is the theory suggested by Crick and Dodge (1944) about processing social information. According to this theory, it is necessary to encode social motivation appropriately, compare it to other related information, and interpret it to appropriately realize social interaction. In situations in which social motivation is better processed, the child’s ability and social skills will increase and his or her interaction with others will be more successful (Morgan et al., 2015).

The intellect has a close relationship with social skills, and individuals having high intellect also have many social skills. When intelligent children are together, they display more enthusiasm and abundant mental activity. It is natural that studying and endeavoring in a space full of intellectual displays and exceptional talents result in increased motivation, consequently using the maximum intellectual talents.

In an investigation conducted by Loannis and Efrosini (2008) about intelligent female students in talent, non-profit, and ordinary schools using a list of teenagers’ social skills, they found that the social skills of talented students were weaker than those of students in non-profit and ordinary schools. In addition, Sugai and Lewis (2009) compared the psychological health and social compatibility of intelligent female students in three educational situations, talent, non-profit, and ordinary schools, in both secondary and high schools. The results of this investigation indicated that the intelligent female students had no meaningful difference in the variables of psychological health and social compatibility in exceptional talent, non-profit, and ordinary schools. In contrast, some researchers have reported that there is a considerable difference between intelligent students who are being educated in schools, especially intelligent students who are educated in ordinary schools, in terms of psychological health and social compatibility. The special schools are more useful for intelligent students and have desirable consequences for them (Altintas & Özdemir, 2015; Kahveci & Atalay, 2015; Rasmussen & Rasmussen, 2015; Yılmaz, 2015).

Hence, in recent years, much attention has been paid to teaching social skills because numerous investigations indicate that insufficiency in social skills has a negative influence on students’ educational performance. It exacerbates learning problems and often results in the appearance of compatibility problems (Parker & Asher, 1993; Yılmaz, 2015). When social skills are mentioned, simple behaviors are considered in various social situations and areas, such as the following:

Putting garbage in special containers,

Cleaning the ground after breaking something,

Applying tableware in an appropriate way,

Observing appropriate eating habits,

Observing appropriate clothing habits in various situations,

Hanging clothes in a special place,

Entering and exiting class silently,

Aligning and observing turns,

Denying others’ requests in a polite way or saying thanks,

handling others’ criticism well (Rawles, 2016),

Using polite words, like saying please to others,

Requesting help from others,

Saying hello and introducing oneself to adults and peers,

Accepting failure in competitive games and saying congratulations to the winner,

Apologizing in essential situations, and

Cooperating with friends in performing tasks (Agran et al., 2016; Yoder, 2015).

Therefore, recognizing and treating children with insufficient social skills is considered an important task for psychologists, advisors, and professionals in education and training (Agran et al., 2016; DiPerna, Lei, Bellinger, & Cheng, 2015).

Social skills

Korinek and Popp (2004) found that many definitions point to verbal and non-verbal behaviors, and some work results in positive social consequences when used in interactions with peers and adults. In another definition, social skills are often considered a complicated collection of skills that include communication, solving problems, making decisions, assertiveness, interactions with peers and groups, and self-management (Loannis & Efrosini, 2008). Matson, Fee, Coe, and Smith (2000) defined social skills as the observable and measurable behaviors that improve independence, acceptability, and a desirable quality of life. These skills are important, and regular performance and insufficiency in social skills are closely associated with psychological disorders and behavioral problems.

Although social skills seem simple, they are affected by psychological structures and basic human characteristics, such as personality, intellect, language, perception, evaluation, attitude, and interaction between the behavior and the environment. Generally, the necessity of interventions because of social skills in all individuals, especially in students who are hearing-impaired, can be expressed according to the results of numerous investigations. Lack of appropriate social skills is the main factor of failure in individuals having hearing problems in social placements. Moreover, it is one reason for losing a job (Betlow, 2005). Teaching social skills can cause a reduction in the number of inappropriate behaviors in class, such as aggression, and can cause an improvement in personal relations between peers and adults (Agran et al., 2016; Flook, Goldberg, Pinger, & Davidson, 2015; Lee et al., 2015). Teaching social skills results in increasing the integration between individuals who are hearing-impaired and ordinary individuals (Welsch et al., 2008).

Emotional and social change in children increases the students’ capacity to concentrate on educational activities, improving psychological health and reducing behavioral problems (Doctoroff, Fisher, Burrows, & Edman, 2016). The components of social skills constitute some univalent processes, such as looking, shaking the head, or some behaviors in social relations, such as saying hello and goodbye. The social processes point to the individual’s ability to create skillful behavior based on related rules and aims and in response to social feedback. This differentiation assesses the individual’s need to supervise the situations and change behavior in response to other individuals’ reactions. Social skills have both evident and non-evident cognitive elements. The non-evident cognitive elements are thoughts and decisions that should be made or carried out in interrelations. These elements also include the purposes and the other individual’s insight, where the reaction to it likely influences the opposite side’s thoughts. Atashak, Baradaran, and Ahmadvand (2013) proposed that social skills, including some behaviors that are applied in successful and appropriate interactions with others, emerge from having a social foundation and cognition, such as social perception and reasoning. Cawthon et al. (2015) pointed out that social skills not only provide the possibility to start and continue mutual and positive relations but also create the ability to achieve the goals of communication (Chen, Wang, & Chen, 2001).

Libermann, Derisi, and Mueser (1989) have decomposed the mutual social interaction to a stage process in which each stage requires a collection of different skills. The first stage of communication requires the receivership skill, including skills required for paying attention and correctly understanding corresponding social information in situations because the adequacy of interpersonal behavior depends on the situation. The occurrence of the correct social behavior depends on the correct recognition of interpersonal and environmental signs, which lead us to influential responses. Examples of receivership skills include appropriate recognition of persons with whom we interact. Indeed, the correct cognition of the feelings and desires expressed by others includes correctly hearing what others express and knowing the personal aims of the individuals interacting with us.

In the next stage, we require processing skills. To become successful in interpersonal encounters, we must know what we should obtain and how we can best acquire it. Selecting the skills that are influential in attaining goals requires the ability to solve problems in a regular and organized style. After the correct perception of social information corresponding to a situation (receivership skills) and recognizing the skills required for interaction (processing skills), the skills should be practiced suitably to complete the interpersonal interchanges successfully.

This third stage of communication requires transmission skills of the actual behaviors involved in the social exchange. The transmission skills include verbal content and how the message communicates to others. Good communication requires correct social perception (receivership skills) and the ability for cognitive planning (processing skills) before giving an answer (influential behavior of transmission skills).

Hargie, Saunders, and Dickson (1994) emphasized these points. First, it should be stated that the social behaviors are targeted. We use these behaviors to gain desirable results. Therefore, unlike behaviors that are accidental or unintentional, social skills have objectives. The second characteristic of skillful social behavior is the inter-relevance of these abilities (i.e., they are different behaviors applied for a special target, and we use them synchronously). The third characteristic of social skills is the fitness to the situation. From the social viewpoint, a person who can change his or her behaviors to correspond to others’ expectations is an expert. In this way, having skillful communication depends on correct (in terms of context) and facilitative application (in terms of behavior) among the methods of appropriate efficient communication with others. The fourth characteristic of social skills is that these skills are separate behavioral units. A person who has social skills can have different and appropriate behaviors. He or she exhibits social abilities in the shape of behavioral performance. This point is one of the obvious characteristics of skillful social communication. Social skills are teachable. Currently, researchers disagree that all social behaviors are teachable. The last characteristic of social skills is that the individuals have cognitive control over these skills. Therefore, a person lacking social skills might have learned the main elements of social skills but might not have the intellectual processes required to use these elements in their interactions (Haase, 2005).

Method

The present investigation is non-experimental. The researcher attempted to investigate the difference between the students’ social skills in ordinary and talented situations to present feedback for enhancement. The statistical sample of this investigation comprises female high school students who are educated in a variety of educational centers (ordinary and exceptional talent schools) of the Alborz province during the 2014–2015 school year.

Because of the extent of the population and the inaccessibility of the student list, the sampling method is cluster sampling. The studied cases include eight government schools and eight all-female exceptional talent schools from different geographical regions in the Alborz province, which were selected by random clustering. It is worth noting that the present investigation was implemented in the following educational context:

a) Exceptional talent schools, which include some schools administered by the National Organization for the Development of Exceptional Talents (NODET), where students of these types of schools are selected by holding an entrance exam, intelligence test, and interview, and

b) Ordinary schools, which are schools administered governmentally by the education and training organization, where students are accepted based on geographical location, without holding an entrance exam and charging tuition.

The first stage was applied on a 1,000-person sample of the Raven intelligence test to assess intelligence. After obtaining the students’ intelligence, the social skills test was conducted on a 200-person sample of females having an intelligence quotient (IQ) higher than 120. To evaluate social skills, the Matson social skills questionnaire was used (1983, cited by Yousefi & Khayer, 2002). This questionnaire includes 56 questions that evaluate the social skills of individuals between 4 and 18 years old. It is based on a five-point Likert scale with a range from 1 (never) to 5 (always). For this scale, five secondary scales were defined as the following five separate factors: 1) appropriate social skills, 2) inappropriate assertiveness, 3) impulsive/recalcitrant, 4) overconfidence, and 5) jealousy/withdrawal.

Results

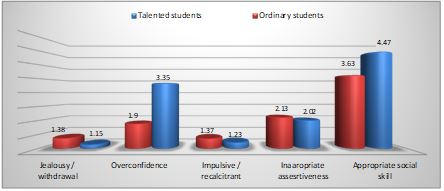

The distribution of social skills among students in the two types of schools is given in Table

In Figure

As reported in Table

Conclusion

All students need to learn appropriate social skills (Agran et al., 2016; Davies., Cooper., Kettler., & Elliott, 2015; Lynch & Simpson, 2010; Rawles, 2016; Sanchez, Brown, & DeRosier, 2015; Yoder, 2015). In recent decades, in investigations of behavioral disorders and social deviations, sociologists and psychologists have found that many disorders have their roots in 1) individuals’ inabilities to analyze themselves correctly and appropriately, 2) the lack of control and personal adequacy counter difficult positions, and 3) the lack of awareness to solve social difficulties and problems in an appropriate way (Zach, Yazdi-Ugav & Zeev, 2016). Therefore, because of the increasing changes and complexities of society, developing social communication and preparing individuals, especially young generations, seem essential to counter difficult positions. The development of society depends on individuals’ scientific and cultural developments and advances, especially for youth, who are the human and intellectual reserves of our country, is important in influencing their development. More research and disquisition on the factors affecting this advance, especially social intellect and skills and their components, are required.

The study compares social skill components among students of ordinary schools and talented schools. The results demonstrated some significant differences among certain components of the social skills between talented and ordinary students. Regarding social psychology, the results of the study showed that there was a significant difference between talented and ordinary students. Accordingly, the talented students had higher scores on the appropriate social skills and overconfidence components, which are consistent with the results of the study by Khodadadi, Tirgari, and Hassanzadeh (2014).

The findings of Yılmaz (2015), Rasmussen and Rasmussen (2015), Kahveci and Atalay (2015), Altintas and Özdemir (2015), Welsh, Parke, Widaman, and Oneil (2001), and Parker and Asher (1987) are in accordance with the results of the present investigation. Teaching social skills is associated with the students’ educational school in some components, such as

Teaching appropriate social skills and providing opportunities and experiences that can increase social interactions enables students to practice and apply social strategies and skills in actual environments and life situations (Chu & Zhang, 2015; Morgan et al., 2015; Lo, Correa, & Anderson, 2015; Yoder, 2015). It is evident that providing these types of opportunities is the responsibility of all people who are interacting with these students and requires programs of integrated and pervasive training.

To improve the current state, some suggestions are given as follows. The influence of social skill training on reducing behavioral and emotional anomalies and improving courteous behaviors should be investigated. The influence of these types of trainings on improving students’ psychological health should be studied. The influence of social skill training programs on other children and students’ self-esteem or those having special needs, such as students who are deaf or have mentally retarded, may be investigated. Social skill training may be considered in in-service training programs for consultants and teachers and in knowledge-increasing programs for parents until they can play the required role in making the students compatible and improving their educational performance.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the teachers and students who participated in this study and the many research assistants and staff who contributed to this project.

References

- Agran, M., Hughes, C., Thoma, C. A., & Scott, L.A. (2016). Employment Social Skills: What Skills Are Really Valued? Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 39(2), 111-120.

- Altintas, E., & Özdemir, A. S. (2015). The Effect of Differentiation Approach Developed on Creativity of Gifted Students: Cognitive and Affective Factors. Educational Research and Reviews, 10(8), 1191-1201.

- Anastasi, A. (1990). Psychological Testing. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

- Atashak, M., Baradaran, B., & Ahmadvand M.A. (2013). The Effect of Educational Computer Games on Students’ Social Skill and Their Educational Achievement. Journal of Technology of Education, 7(4), 297-305.

- Betlow, M. (2005). The effect of social skills intervention on the emotional intelligence of children with limited social skills. Unpublished thesis Hall University.

- Cawthon, S. W., Caemmerer, J. M., Dickson, D. M., Ocuto, O. L., Ge, J., & Bond, M. P. (2015). Social Skills as a Predictor of Postsecondary Outcomes for Individuals Who Are Deaf, Applied Developmental Science, 19(1), 19-30.

- Chen, H., Wang, Q., & Chen, X. (2001). School achievement and social behaviors: A cross-lagged regression analysis. Act a Psychological Sinica, 33(6), 532-536.

- Chu, Y. A., & Zhang, L.C. (2015). Are Our Special Education Students Ready for Work? An Investigation of the Teaching of Job-Related Social Skills in Northern Taiwan. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 62(6), 628-643.

- Crick, N.R., & Dodge, K.A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information in children’s social adjustment. Psychological social bulletin, 115, 74-101.

- Davies, M., Cooper, G., Kettler, R. J., & Elliott, S. N. (2015). Developing Social Skills of Students with Additional Needs within the Context of the Australian Curriculum. Australasian Journal of Special Education, 39(1), 37-55.

- DiPerna, J. C., Lei, P., Bellinger, J., & Cheng, W. (2015). Efficacy of the Social Skills Improvement System Classwide Intervention Program (SSIS-CIP) Primary Version. School Psychology Quarterly, 30(1), 123-141.

- Doctoroff, G. L., Fisher, P. H., Burrows, B. M., & Edman, M. T. (2016). Preschool Children's Interest, Social-Emotional Skills, and Emergent Mathematics Skills. Psychology in the Schools, 53(4), 390-403.

- Flook, L., Goldberg, S.B., Pinger, L., & Davidson, R.J. (2015). Promoting prosocial behavior and self-regulatory skills in preschool children through a mindfulness-based Kindness Curriculum. Dev Psychol. 51(1), 44-51.

- Gresham, F. M. (2016). Social Skills Assessment and Intervention for Children and Youth. Cambridge Journal of Education, 46(3), 319-332.

- Haase, V.G. (2005). The Matson Evaluation of Social Skills with Youngsters (MESSY) and its Adaptation for Brazilian children and adolescents. International Journal of Psychology, 39(2) 239-246.

- Hargie, O., Saunders, C., & Dickson, D. (1994). Social Skills in Interpersonal Communication (3rd edition). New York and London: Routledge

- Kahveci, N. G., & Atalay, Ö. (2015). Use of Integrated Curriculum Model (ICM) in Social Studies: Gifted and Talented Students' Conceptions. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 59, 91-111.

- Khodadadi, M., Tirgari, A., & Hassanzadeh, R. (2014). Comparing Five Major Personality Traits in Gifted and Ordinary Students. International Journal of Basic Sciences & Applied Research, 3(10), 756-759.

- Lee, S.Y., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., Makel, M. C., & Putallaz, M. (2015). Gifted students’ perceptions of an accelerated summer program and social support. Gifted Child Quarterly, 59, 265-282.

- Liberman, R. P., Derisi, W. J., & Mueser, K. T. (1989). Social Skill Training for Psychiatric Patients. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Baccon.

- Lo, Y., Correa, V. I., & Anderson, A. L. (2015). Culturally Responsive Social Skill Instruction for Latino Male Students. Journal of Positive Behaviour Interventions, 17(1), 15-27.

- Loannis, A., & Efrosini, K. (2008). Nonverbal social interaction skills of children with learning disabilities. Research in developmental disabilities, 29, 1-10.

- Lynch, S. A., & Simpson, C. G. (2010). Social skills: Laying the foundation for success. Dimensions of Early Childhood, 38 (2), 3-12.

- Matson, J. L., Fee, V. E., Coe, D. A., & Smith, D. (2000). A social skills program for developmentally delayed preschoolers. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 20(4), 428-433.

- Morgan, J., Hsiao, Y. J., Dobbins, N., Brown, N., & Lyons, C. (2015). An Observation Tool for Monitoring Social Skill Implementation in Contextually Relevant Environments. Intervention in School and Clinic, 51(1), 3-11.

- Parker, J. G., & Asher, S. R. (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: link with peer group acceptance and feeling of loneliness and social dissatisfaction, Dev Psyche, 29(2), 611-621.

- Parker, J., & Asher, S.R. (1987). Peer relations and the later personal adjustment: Are low-accepted children at risk? Psychological Bulletin, 102(3), 357-389.

- Rasmussen, A., & Rasmussen, P. (2015). Conceptions of Student Talent in the Context of Talent Development Conceptions of Student Talent in the Context of Talent Development, International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education (QSE), 28(4), 476-495.

- Rawles, J. (2016). Developing Social Work Professional Judgment Skills: Enhancing Learning in Practice by Researching Learning in Practice. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 36 (1), 102-122.

- Sanchez, R. P., Brown, E., & DeRosier, M.E. (2015). Teaching Social Skills: An Effective Online Program. Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED562528.pdf

- Slaby, T., & Gaura, T. (2003). Self-efficacy and personal goal setting, American Education Research Journal, 29,663-669.

- Slawmouski, L., & Dann, P. (1996). Training blind adolescents in social skills, Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness, 19, 199-204.

- Strayer, K. (1989). The important of social skills in the employment interview, Education of visually Handicapped, 14, 7-12.

- Sugai, G., & Lewis, T. J. (2009). Preferred and promising practices for social skills instruction. Focus on Exceptional Children, 29(4), 1-16.

- Welsh, M., Parke, R., Widaman, K., & Oneil, R. (2001). Linkages between children’s social and academic competence: Longitudinal analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 39(6), 463-482.

- Yılmaz, D. (2015). A qualitatıve study to understand the social and emotıonal needs of the gıfted adolescents, who attend the scıence and arts centers in Turkey. Educational research and review, 8(10), 1109-1120.DOI: 10.5897/ERR2015.2134[Article Number: 41951D652393]

- Yoder, N. (2015). Social and Emotional Skills for Life and Career: Policy Levers That Focus on the Whole Child. Center on Great Teachers & Leaders at American Institutes for Research. Policy Snapshot, 1-14. Retrieved from http://www.gtlcenter.org/sites/default/files/SEL_Policy_Levers.pdf

- Yousefi, F., & Khayer, M. (2002). A Study on the Reliability and the Validity of the Matson Evaluation of Social Skills With Youngstres (Messy) and Sex Differences in Social Skills of High School Students in Shiraz, Iran. Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities of Shiraz University, 18(36), 159-170.

- Zach, S., Yazdi-Ugav, O., & Zeev, A. (2016). Academic Achievements, Behavioral Problems, and Loneliness as Predictors of Social Skills among Students with and without Learning Disorders. School Psychology International, 37(4), 378-396.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

22 November 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-015-0

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

16

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-919

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Daraee, M., Salehi, K., & Fakhr, M. (2016). Comparison of Social Skills between Students in Ordinary and Talented Schools. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2016: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 16. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 512-521). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.11.52