Students’ Involvement in School and Parental Support: Contributions to the Socio-Educational Intervention

Abstract

Dietary fibre (DF) is recognized as a major determinant for improvement of health. Hence the means of information through which people become aware of its benefits are crucial and this work aimed at studying the sources of information about DF. Factors such as age, gender, level of education, living environment or country were evaluated as to their effect on the selection of sources and preferences. For this, a descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out in a sample of 6010 participants from 10 countries. For the analysis were used descriptive statistics, crosstabs and chi square test, and factor analysis with Varimax rotation. The results showed that mostly the information about DF comes from the internet, but the participants recognize that television might be a most suitable way to disseminate information about DF. The results also indicated differences between age groups, genders, levels of education, living environments and countries. The internet, the preferred source of information, got highest scores for Hungary, for urban areas, for university level of education and for female gender. The radio, the least scored source of information, was preferred in Egypt, for men and with lower education (primary school). As a conclusion, people get information through the internet due to easy access. However, it is to some extent a risk given the impossibility to control de information made public on the internet. The role of health centers and hospitals as well as schools should definitely be increased, as a responsible way to ensure correct information.

Keywords: Dietary fibreInformation mediaInternetTelevisionSurvey

Introduction

Dietary fibre (DF) has long been recognised as healthy, so much that the European Food safety Authority (EFSA) allows health claims on dietary fibre (Mackie, Bajka, & Rigby, sem data). Some fibres act as prebiotics, such as dietary fibre preparations containing resistant dextrins, branched dextrins, resistant maltodextrins and soluble corn fibre. Prebiotics reach the colon without being hydrolysed and are selectively metabolized by health-positive bacteria like bifidobacteria and lactobacilli thus providing a beneficial effect on the host health (Gidley, 2013; Sabater, Prodanov, Olano, Corzo, & Montilla, 2016).The consumption of prebiotic substances may be one of the factors preventing overweight and obesity (Barczynska et al., 2015).

Over the last years a high degree of information has been discovered about the different compounds present in DF, such as prebiotics (with certain fermentability profiles of specific substances and their interaction with colonic microflora) or even bioactive compounds closely associated with DF (exerting important antioxidant properties with protective effect on the human body (Giuntini & Menezes, 2011; Saura-Calixto, 2011). However, the benefits from an adequate ingestion of dietary fibre are far wider and include: preventing cardiovascular diseases, atherosclerosis, type 2 diabetes, constipation, gastrointestinal types of cancer and facilitating good colonic health (Sumczynski, Bubelová, & Fišera, 2015; Zhu, Du, & Xu, 2015; Zhu, Du, Zheng, & Li, 2015).

The beneficial effects and effectiveness of DF depend firstly on fibre intake but, not exclusively, because factors like fibre composition, organisational structure, physicochemical characteristics or associated bioactive compounds, which have been found directly related to its plant source and preparation methods have also demonstrated to be implicated on the way DF acts on the human body (Elleuch et al., 2011).

Education is pivotal for achieving a desired level of knowledge so as to make appropriate food choices. Differences in diet quality may contribute to different health status across socioeconomic groups, so that, in general, people from higher socioeconomic status tend to adhere to higher-quality diets. The disparities in diets and health have also been lined to neighbourhood food environments, for their influence of the dietary patterns (Acar Tek et al., 2011; Drewnowski, Aggarwal, Cook, Stewart, & Moudon, sem data; Rahmanian, Gasevic, Vukmirovich, & Lear, 2014).

The knowledge about DF as a food component is sometimes low, due to neglected involvement in producing effective ways of educating people about the topic. The sources of information are therefore important to identify fragilities and plan interventions aimed at increasing the level of education (Martinho et al., 2013). Still, because of the importance of DF as an agent of protection and promotion of human well-being and health, more recently there has been an increase in knowledge about DF (Macagnan, da Silva, & Hecktheuer, 2016).

This work aimed at evaluating the sources of information about DF on a sample population original from 10 different countries. Factors like age, gender, level of education, living environment or country were studied in relation to their effect regarding the data obtained for information about DF.

Materials and methods

Instrument

The questionnaire was structured into different sections, designed to gather, among other aspects, information about the sources of information regarding dietary fibre, given its importance as a healthy food component.

The socio-demographic characteristics like age, gender, level of education, country and living environment were addressed in the beginning of the questionnaire. The questionnaire also contained a section about the sources of information from where the respondents get information about dietary fibre. The respondents were asked to classify the different options on a scale from 1 (least important) to 6 (most important). There were two questions: “Where do you usually find information about dietary fibre” and “What means of communication do you consider the most appropriate to encourage the consumption of dietary fibre”, and for both the answering options were: (a) Health centres/hospitals, (b) Radio, (c) Television, (d) School, (e) Magazines/books, (f) Internet.

Data collection

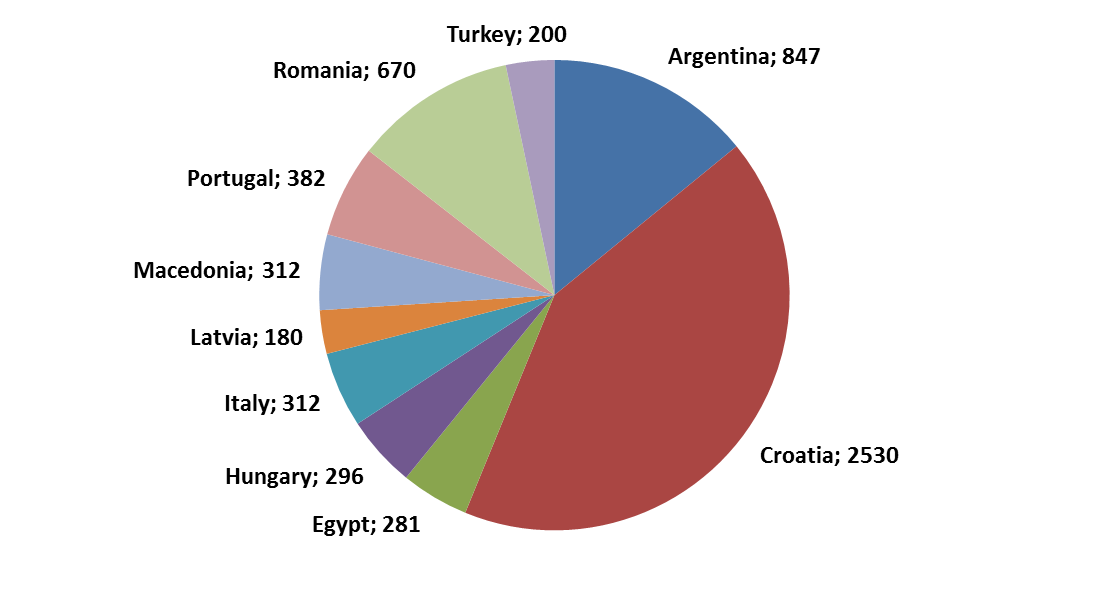

The study was conducted with 6010 participants resident in several countries from different continents (Argentina, Croatia, Egypt, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Macedonia, Portugal, Romania, Turkey). The participation included different countries because these integrated a project of the CI&DETS Research Centre (IPV, Viseu, Portugal).

The participation in the survey was voluntary, and the questionnaire was applied by direct interview only to adult citizens, after verbal informed consent was obtained. The sample was selected attempting to reach different sectors of the population, namely in terms of age, literacy, gender or geographical area of residence, including people from different cities and smaller villages in each of the participating countries.

All the answers were kept anonymous and no personal data were ever collected or related to any answers, thus protecting the participants. Furthermore, all ethical issues were strictly guaranteed when designing the questionnaire and applying the survey.

Statistical analyses

For all data analysis the software SPSS, from IBM Inc. (version 22) was used. For the analysis of the data basic several descriptive statistics tools were used. Also the crosstabs and the chi square test were used to assess the relations between some of the variables under study. The level of significance considered was 5%.

A factor analysis (FA) was applied to the different sources of information, to observe if there was a grouping structure between some of them. Firstly, the data was tested to verify their applicability for FA by Principal Component Analysis (PCA), by means of the following elements: the correlation matrix between the variables included in the study; the Bartlett's test to check for intercorrelation between variables; and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of adequacy of the sample (KMO) (Broen et al., 2015). After confirmation of the adequacy of the data, then the FA was applied with extraction by PCA method and Varimax rotation with Kaiser Normalization, i.e., with the number of components determined by eigenvalues ≥ 1. In all cases, the communalities were calculated to show the percentage of variance explained by the factors extracted (Broen et al., 2015). Factor loadings with an absolute value exceeding 0.4 were used, because this lower limit accounts for about 16% of the variance in the variable (Rohm & Swaminathan, 2004; Stevens, 2009).

Results and Discussion

Sample characterization

This study was undertaken simultaneously in ten different countries originating from three different continents (Europe, America, Africa), as shown in Figure

The total number of participants was 6010, from which 65.7% were female and 34.3% were male. The average age of the participants was 34.5±13.7 years, ranging from 18 to 84 years. The average age of the female participants was slightly lower (33.5±13.3 years) when compared to the average age of the male participants (36.5±14.4 years). The variable age was classified into categories according to: young adults, from 18 to 30 years (accounting for 50.0%); average adults, from 31 to 50 years (representing 34.5%); senior adults, from 51 to 65 years (corresponding to 13.5%); and finally elderly, over 65 (representing 2.0%).

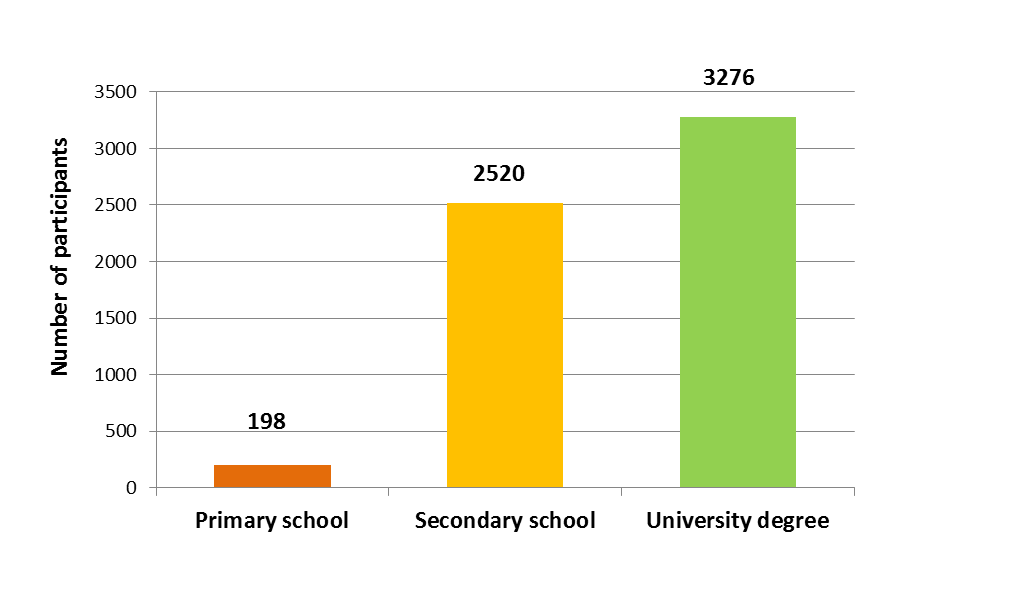

The majority of the participants had a high level of education (55% with a university degree), while 42% had competed secondary school and just 3% had the lowest level of education (primary school) (Figure

Sources of information about DF

The level of information about nutritional and health related facts is largely dependent on the sources of information. There are different ways to disseminate information and allow keeping the public aware of the issues related to food fibres. Hence, this was one of the aspects evaluated in the present study by two questions: one related to the public’s perceptions about the way information is presently being disclosed and also what would be the most appropriate means, in their opinion, to disseminate information about fibres.

The results in Table

The least pointed source of information about DF was radio (2.7±1.6), and was also indicated as not so convenient for the transmission of information (2.9±1.6) (Table

Influence of social factors on the perception of the sources of information

Table

Internet was the most relevant means of information as seen before by the results in Table

Also the level of education was found to significantly influence the results (p = 0.000), so that the participants with a lower level of education, primary school, gave considerably lower scores for internet (3.4±2.0) when compared to secondary school or university level (4.4±1.8, in both cases) (Table

Regarding the living environment, again significant differences were found with a higher average score for urban when compared to rural areas (4.4±1.8 against 4.1±1.9, respectively) (Table

With respect to the countries at study, statistically significant differences were found (p = 0.000), being given more importance for internet as a source of information about DF in Hungary (4.9±1.4) whereas in Egypt internet was not so much recognized as a good source of information (3.5±2.0) (Table

The results in Table

The radio was the media considered least used to get information about DF, as seen previously. The socio-demographic variables were associated with radio, except for living environment, for which the differences between living in urban or rural areas did not induce significant differences in the rating given by the participants in the survey. Although radio had a lowest expression, still it was scored as having some importance, particularly by men (2.9±1.6), by participants with primary school (3.5±1.6) and by people from Egypt (3.5±1.7).

Table

The results in Table

The results in Table

Factor analysis

The correlation matrix showed that there were some correlations between the variables, with some values around or higher than 0.4, although jus moderately high (the highest value was 0.434, which was the correlation between the variables radio and internet). In this way, the values are indicative that it is possible to apply FA, being this also corroborated by the results of the Bartlett's test, because the p-value was highly significant (p < 0.0005), thus leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis that the correlation matrix was equal to the identity matrix. However, the value of KMO was weak (0.398) according to the classification of Kaiser and Rice (Kaiser & Rice, 1974).

The solution obtained by FA with PCA and varimax rotation retained two components, based on the Keiser criterion to consider eigenvalues greater than one (1.773 and 1.531, in the present case). The percentages of total variance explained by the factors were 29.6% for factor 1 (F1) and 25.5% for factor 2 (F2), with a total variance explained of 55.1%.

The variable Internet had the largest fraction of its variance explained by the FA rotated solution, corresponding to 66.8%, followed by variable Television, with 65.9% of the variance explained. The variable School had a lower communality (0.376), corresponding to a lower percentage of its variance explained (only about 40%), and all other variables had communalities higher than 0.400.

The rotation converged in three iterations and resulted in two factors, as shown in Table

Conclusion

The results in the present study allowed concluding that the majority of the information about DF comes from searches made through internet, but the participants recognize that television might be the best media to disseminate information about health related subjects such as diet and particularly DF. The results further showed differences between age groups, genders, levels of education, living environments and countries. The internet got highest scores for Hungary, for urban environment, for younger people, university level of education and for female gender. For the books the highest scores were for middle aged people, females, with university education and for Hungary and Latvia. TV was preferred by people from Macedonia, with university education, average adults or elderly and of the male gender. School was identified as a source of information in Portugal and Turkey, in rural environments, by young adults and female participants. Health centres got highest scores for Egypt and Argentina, rural areas, lower education (primary school), elderly people and female gender. The radio, the least scored source of information, was preferred in Egypt, for men, for participants with primary school and elderly.

The factor analysis showed that the six sources of information could be grouped into two factors, one associated with sources potentially considered more reliable (hospitals, schools and television) and the other associated with less reliable sources (radio, internet or magazines). This is important, because it allows focusing on the best ways to disseminate information about a healthy eating, including DF regularly in the diet, so as to contradict the present trend to look for information on the internet.

Acknowledgements

This work was prepared in the ambit of the multinational project from CI&DETS Research Centre (IPV - Viseu, Portugal) with reference PROJ/CI&DETS/2014/0001.

References

- Acar Tek, N., Yildiran, H., Akbulut, G., Bilici, S., Koksal, E., Gezmen Karadag, M., & Sanlıer, N. (2011). Evaluation of dietary quality of adolescents using Healthy Eating Index. Nutrition Research and Practice, 5(4), 322–328.

- Barczynska, R., Slizewska, K., Litwin, M., Szalecki, M., Zarski, A., & Kapusniak, J. (2015). The effect of dietary fibre preparations from potato starch on the growth and activity of bacterial strains belonging to the phyla Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria. Journal of Functional Foods, 19, Part A, 661–668.

- Broen, M. P. G., Moonen, A. J. H., Kuijf, M. L., Dujardin, K., Marsh, L., Richard, I. H., … Leentjens, A. F. G. (2015). Factor analysis of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 21(2), 142–146.

- Dovey, T. M., Taylor, L., Stow, R., Boyland, E. J., & Halford, J. C. G. (2011). Responsiveness to healthy television (TV) food advertisements/commercials is only evident in children under the age of seven with low food neophobia. Appetite, 56(2), 440–446.

- Drewnowski, A., Aggarwal, A., Cook, A., Stewart, O., & Moudon, A. V. (sem data). Geographic disparities in Healthy Eating Index scores (HEI-2005 and 2010) by residential property values: Findings from Seattle Obesity Study (SOS). Preventive Medicine.

- Elleuch, M., Bedigian, D., Roiseux, O., Besbes, S., Blecker, C., & Attia, H. (2011). Dietary fibre and fibre-rich by-products of food processing: Characterisation, technological functionality and commercial applications: A review. Food Chemistry, 124(2), 411–421.

- Gidley, M. J. (2013). Hydrocolloids in the digestive tract and related health implications. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science, 18(4), 371–378.

- Giuntini, E. B., & Menezes, E. W. (2011). Funções Plenamente Reconhecidas de Nutrientes - Fibra Alimentar (Brasil International Life Sciences Institute, Vol. 18). Brazil.

- Kaiser, H. F., & Rice, J. (1974). Little Jiffy, Mark Iv. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 34(1), 111–117.

- Lin, C. A., Atkin, D. J., Cappotto, C., Davis, C., Dean, J., Eisenbaum, J., … Vidican, S. (2015). Ethnicity, digital divides and uses of the Internet for health information. Computers in Human Behavior, 51, Part A, 216–223.

- Macagnan, F. T., da Silva, L. P., & Hecktheuer, L. H. (2016). Dietary fibre: The scientific search for an ideal definition and methodology of analysis, and its physiological importance as a carrier of bioactive compounds. Food Research International, 85, 144–154.

- Mackie, A., Bajka, B., & Rigby, N. (sem data). Roles for dietary fibre in the upper GI tract: The importance of viscosity. Food Research International.

- Martinho, C., Correia, A., Goncalves, F., Abrantes, J., Carvalho, R., & Guine, R. (2013). Study About the Knowledge and Attitudes of the Portuguese Population About Food Fibres. Current Nutrition & Food Science, 9(3), 180–188.

- Rahmanian, E., Gasevic, D., Vukmirovich, I., & Lear, S. A. (2014). The association between the built environment and dietary intake - a systematic review. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 23(2), 183–196.

- Ramos, C., & Navas, J. (2015). Influence of Spanish TV commercials on child obesity. Public Health, 129(6), 725–731.

- Rohm, A. J., & Swaminathan, V. (2004). A typology of online shoppers based on shopping motivations. Journal of Business Research, 57(7), 748–757.

- Sabater, C., Prodanov, M., Olano, A., Corzo, N., & Montilla, A. (2016). Quantification of prebiotics in commercial infant formulas. Food Chemistry, 194, 6–11.

- Saura-Calixto, F. (2011). Dietary fiber as a carrier of dietary antioxidants: an essential physiological function. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 59(1), 43–49.

- Stevens, J. P. (2009). Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, Fifth Edition (5 edition). New York: Routledge.

- Sumczynski, D., Bubelová, Z., & Fišera, M. (2015). Determination of chemical, insoluble dietary fibre, neutral-detergent fibre and in vitro digestibility in rice types commercialized in Czech markets. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 40, 8–13.

- Whitten, P., Kreps, G. L., & Eastin, M. S. (2011). E-Health: The Advent of Online Cancer Information Systems. New York, USA: Hampton Press.

- Zhu, F., Du, B., & Xu, B. (2015). Superfine grinding improves functional properties and antioxidant capacities of bran dietary fibre from Qingke (hull-less barley) grown in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Journal of Cereal Science, 65, 43–47.

- Zhu, F., Du, B., Zheng, L., & Li, J. (2015). Advance on the bioactivity and potential applications of dietary fibre from grape pomace. Food Chemistry, 186, 207–212.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

22 November 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-015-0

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

16

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-919

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Felizardo, S. A., Cantarinha, D., Alves, A. B., Ribeiro, E. J., & Amante, M. J. (2016). Students’ Involvement in School and Parental Support: Contributions to the Socio-Educational Intervention. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2016: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 16. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 278-287). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.11.29