Abstract

The paper represents a critical analysis of the options ahead of maritime universities in terms of number of students admitted, particularly in periods of industry downturns. The study refers to the global maritime industry and analyses the patterns of the industry cycle. These patterns are characterised in macroeconomic terms by peaks, troughs and secular long term trends. The current maritime industry faces chronic global trade imbalances in the context of slow global economic. The secular trend has flattened and the industry is clearly in the downturn. These patterns envisage both cyclical and structural unemployment components. This paper addresses the maritime universities’ options associated with cyclical unemployment of maritime graduates. These options include procyclical, counter-cyclical or level capacity approaches in the students’ admission capacity planning, depicted by the duration of studies and the offset between admission and graduation. The analysis overlays the graduate studies and industry cycles and proposes to evaluate the different scenarios based on industry outlook and to determine the optimum admission policy solution.

Keywords: Maritimegraduateadmissionindustrycyclicalunemployment

Introduction

The global maritime industry operates in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous environment.

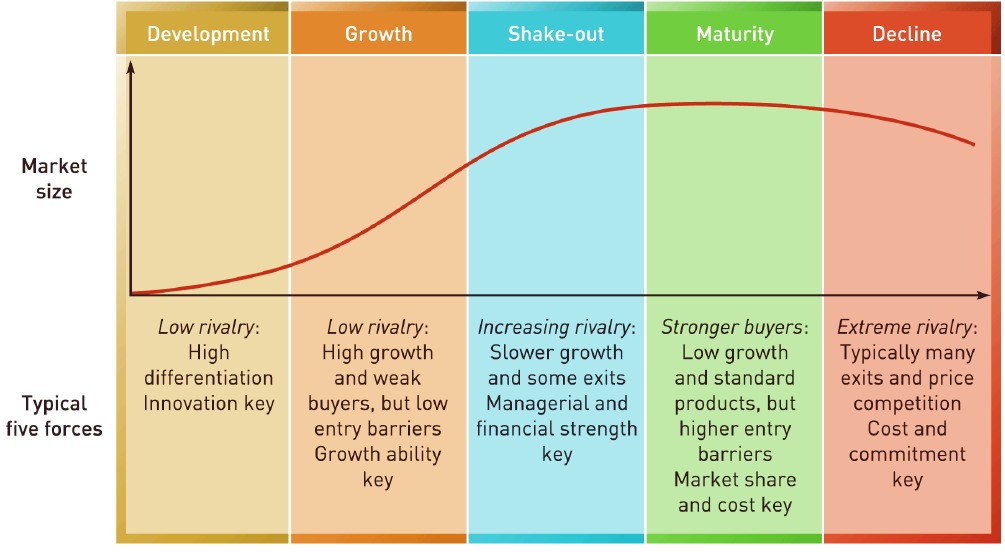

In the sense of Johnson et al. (2014) the industry operates in life cycles (Fig 1). Currently, the maritime

industry faces chronic global trade imbalances in the context of slow global economic. The industry

therefore passes through a period of decline, characterized by extreme rivalry, mergers and

acquisitions. The private equity investors which crowded in the industry and imbalanced the supply of

ships give signs of leaving the industry possibly at loss.

The above model adopts the cyclic view of the industry. Considering historical qualitative data, the

duration of a full cycle in the maritime industry is in range of 5 years, with variations depending on the

evolution of commodities supply and demand and the amplitude of capital expenditures during the

cycle.

Analysis of Admission in Maritime Higher Education

The maritime universities operating in the above macroeconomic environment face challenges in

terms of strategic choice for admission capacity planning. As maritime education service providers, a

solution for the problem at hand may be increased market penetration to achieve organizational growth

(Ansoff, 1965). However, this solution may be short lived, because of the risk of seafarers’ oversupply

and subsequent further drop in candidates’ demand for maritime education. Another drawback of this

approach may rest with the social responsibility and ethical issues in the sense of Freeman’s (1984)

stakeholder theory.

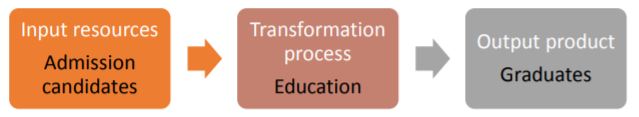

We propose the perspective of maritime education through the lenses of the transformation process

model (Slack, Chambers & Johnson, 2010). We modelled the maritime education into the framework

(Fig 2), considering the admission candidates as input resources, the education as transformation

process, leading to the output of graduates.

It is of note that, in the context, we view the output of education as product, rather than service

provided to the marine market.

The academic cycle for engineering studies in Europe, in accordance with the Bologna Accords

(European Commission, 2016) has a duration of 4 years. The durations of the maritime education and

maritime industry cycles entail the strong possibility that the products of education may be brought to a

declining market. The academic education cycle is regulated, while the industry cycle remains

uncertain. Managing the students’ admission is therefore a wicked task and a matter of capacity

planning (Gunther, 2006).

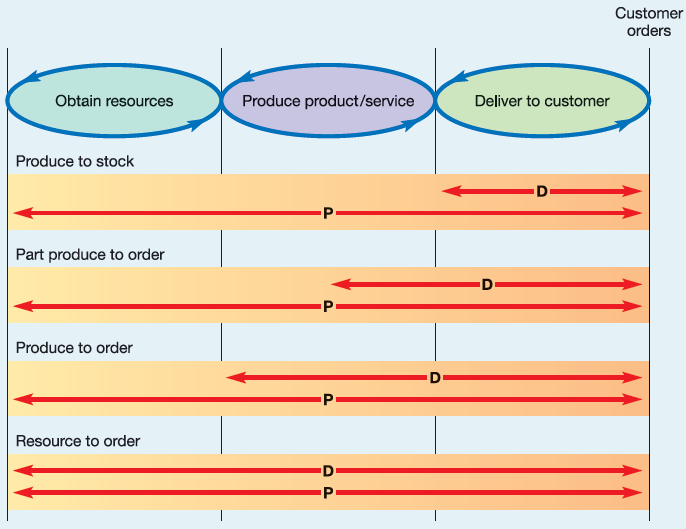

Slack, Chambers and Johnson (2010) draw the academic theoretical approach in capacity planning

and control, depicted in Fig 3, where: P – total throughput time, and D – customers’ waiting time.

However, considering the graduates’ long lead time and the industry volatile changes in demand,

solutions such as resource to order and produce to order carry social responsibility issues. These

solutions may be put in practice through strategic alliances between universities and ship Owners and

managers. These would carry additional risk, but would benefit from quality and availability of skilled

labour.

In absence of the above, the generic approaches on capacity planning are to absorb the demand,

adjust output to meet the demand or change the demand. The first two alternatives draw on the work of

Sasser (1976) with reference to level capacity and chase demand.

The level capacity suggests maintaining a constant level of students admitted to maritime studies.

The drawback of this approach, in the context of the cyclic maritime industry, is that universities would

lose organizational capabilities and market share during periods of industry growth. During periods of

industry decline, a lag between students’ graduation and their absorption by the market is expected.

Maritime labour supply and demand

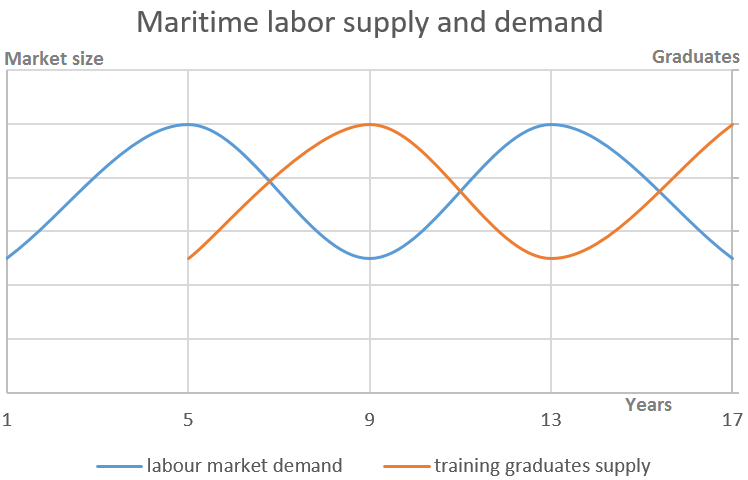

The chase demand approach envisages admitting students to meet the demand. While this approach

has merits, a tendency to reduce the number of students admitted to maritime studies has been observed

during industry decline, when the demand for maritime labour is low. This may be the result of reduced

students’ demand for maritime education and by deliberate universities’ strategic choice. The line of

thought of this article draws attention on the drawback of such an approach. As set out above, the

education process has duration of four years, and the output products are considered long lead items.

Therefore, shaping the admission policy to meet the current demand is a pro-cyclical approach, leading

to disproportionate supply relative to future demand. Results of such policy may take the shape

depicted in Fig 4.

We argue that it is rather the role of the education institutions to act proactively and counter

cyclical, through planning the supply to meet industry demand.

With regards to the change of demand, Slack, Chambers and Johnson (2010) expanded on Sasser’s

(1976) work and considered the notion of demand management. This suggests that organizations may

attempt to change or influence demand, to fit the available capacity. This may be achieved through

lowering price.

Since maritime universities do not control the graduates’ salary expectations and the global demand

for maritime officers is linked to the number of ships in operation, this does not appear a viable

solution.

An alternative solution to change the demand is to diversify academic curricula and address

market’s unexpressed needs. This is rather a product expansion approach, which falls under

organizations’ development capabilities.

Conclusions

Forecasting of supply and demand is of assistance in planning students’ admission in maritime

education. Maritime universities would benefit from linking their organization’s strategy to market

forecasts.

Planning should envisage at least a complete cycle of the concerned industry. Delivery of maritime

academic education is a long lead process and graduates need to meet future demand, not the mere

present. The pro-cyclical approach in students’ admission leads to dysfunctional supply of maritime

graduate. A counter cyclical approach is preferred, yet considering the overall industry trend and the

phase of the industry lifecycle.

The diversification of academic curricula should not be discounted as a potential solution to benefit

the maritime cluster, including universities, labour market, ship Owners, managers, classification

societies, traders, insurers and the banking system.

References

- Johnson, G., et al. (2014). Exploring strategy – Text and cases. 10th edition. Harlow: Pearson Education. Ansoff, H.I. (1965). Corporate strategy: An analytic approach to business policy for growth and expansion. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Freeman, R.E. (1984). Strategic management: a stakeholder approach. Boston, Pitman.

- Slack, N., Chambers, S., & Johnson, R. (2010). Operations management. 6th edition. Harlow: Financial Times Prentice Hall.

- European Commission (2016). The Bologna process and the European higher education area. Brussels: European Commission.

- Gunther, N.J. (2006). Guerrilla capacity planning: A tactical approach to planning for highly scalable applications and services. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

- Sasser, W.E. (1976). Match Supply and Demand in Service Industries. Harvard Business Review, November - December.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

04 October 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-014-3

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

15

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1115

Subjects

Communication, communication studies, social interaction, moral purpose of education, social purpose of education

Cite this article as:

Acomia, O., & Acomib, N. (2016). Critique to Pro-Cyclical Admission in Maritime Higher. In A. Sandu, T. Ciulei, & A. Frunza (Eds.), Logos Universality Mentality Education Novelty, vol 15. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 16-20). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.09.3