Abstract

Over the years, important scientific and political efforts were made towards understanding poverty and finding the best approach for fighting it. Fresh and very interesting ideas are produced in the new scientific domain of behavioural economics. Behavioural economics aims to increase the psychological realism of the economic models, integrating inputs regarding preferences, emotions, values and analysing their influences on decision making. There are two main approaches on poverty in the behavioural economics literature. The first one uses rigorous scientific experiments to demonstrate that the context of scarcity creates a cognitive tax and cognitive depletion, associated with decisions and behaviours that only end up in perpetuating poverty. The second one, also supported by certain scientific studies, shows that poverty creates a type of mental framing that negatively affects the individuals` capacity to aspire. Our study builds on this idea of poverty generated mind-set and aspiration deficit. Using data offered by the World Values Survey (2012) for Romania, we analyse the differences in perceptions and values, of both the most affluent and the least affluent. The particular focus is concentrated on perceived life satisfaction, control over life course, attitude towards work, social and communitarian involvement, openness towards novelty and risk taking.

Keywords: Povertybehavioural economicspsychology of povertyvaluesaspirations

Introduction

Samson (2015: 1) offered a comprehensive definition of Behavioural Economics (BE) as “the study

of cognitive, social, and emotional influences on people's observable economic behaviour”.

Behavioural economics aims to incorporate important empirical, experimental research results from

other scientific domains, mainly psychology, into the economic theory, in order to offer a more

adequate, realistic reflection of reality. The economic models, built upon the neoclassic principles, lack

psychological realism, mainly due to the fact that they intentionally simplify the functioning of the

human individual as an economic agent. This generates certain distortions on the results of its models

and predictions. The behavioural economics acts on correcting these distortions, offering information

on human characteristics that, once integrated into the economic models, would offer a better

understanding of economic realities.

“According to BE, people are not always self-interested, cost-benefit-calculating individuals with

stable preferences, and many of our choices are not the result of careful deliberation. Instead, our

thinking tends to be subject to insufficient knowledge, feedback, and processing capability, which often

involves uncertainty and is affected by the context in which we make decisions. We are unconsciously

influenced by readily available information in memory, automatically generated feelings, and salient

information in the environment, and we also live in the moment, in that we tend to resist change, be

poor predictors of future preferences, be subject to distorted memory, and be affected by physiological

and emotional states. Finally, we are social animals with social preferences, such as those expressed in

trust, altruism, reciprocity, and fairness, and we have a desire for self-consistency and a regard for

social norms.” (Samson, 2015: 1)

The inputs of behavioural economics offer a plus of information and scientific value mostly to

research on economic choice, taking into consideration the individual preferences, emotions, values

and their influences on decision making.

Most recently, the 2015 World Bank Report -

2015)synthesised “hundreds of empirical papers on human decision making”, concluding that there are

three main ideas about the human cognitive psychology that should be considered as a research starting

point for designing and implementing developmental policy. First, most of our judgments and choices

are automatically made, without conscious deliberation – this was called “thinking automatically.”

Second, people’s thinking depends on other people’s behaviours, attitudes, expressed ideas and values -

this was called “thinking socially.” Third, individuals in a community and, furthermore, in a society

share a common perspective on the functioning of the world around them - this was called “thinking

with mental models.” What happens around us, in our social environment, shapes our mind. “People’s

mental models shape their understanding of what is right, what is natural, and what is possible in life.”

(The World Bank, 2015)

These three characteristics of human cognition are also substantiating the behavioural economics

research on poverty.

Mullainathan and Shafir (2013) focused their extensive work on the behavioural approach of

poverty, talking about a cognitive tax/burden that poor people face, making it harder for them to think

deliberatively, and pushing them towards automatic decision making. This is the mechanism that

explains, according to the two authors, certain poverty perpetuating behaviours exhibited by the poor:

underinvestment in education, non-take-up of benefits, insufficient saving and excessive borrowing.

In the past, this type of behaviour was explained through the concept of “culture of poverty”, a

distinct culture with specific beliefs, attitudes, values and practices (Lewis, 1966). Yet, this approach

was strongly criticized, as it seemed to put the blame of poverty on the poor (Ryan, 1976).

The experimental research of Mullainathan and Shafir (Mullainathan & Shafir, 2013; Mullainathan

& Shafir, 2014) demonstrated that this type of behaviour is not necessarily a consequence of the culture

of poverty, but it is rather due to the demanding context of poverty, that consumes mental resources,

making it harder to focus the necessary attention on cognitively demanding tasks, even though they

might be crucial for the long term economic well-being of the individual (see also Mani, et. al., 2013).

The cognitive burden imposed by scarcity was underlined in experimental situations. In one of the

most interesting studies, the research subjects were put under observation both in a scarcity situation

and in a non-scarcity situation, discovering that, the scarcity setting was associated to worse results for

a series of cognitive tests compared to the non-scarcity setting. The experiment controlled other factors

that could have explained this gap (The World Bank, 2015).

Experiments show that even the exposure to hypothetical scenarios of scarcity captures the mental

resources and it is associated to weaker performances on later applied cognitive tests (Mani et. al.,

2013).

A study consisting in inducing “poverty” and “affluence” among relatively well-off subjects,

through their endowment with certain items, proved that middle class individuals, placed briefly in a

context of scarcity, exhibit decision-making patterns typically associated with poverty (excessive

borrowing) (The World Bank, 2015).

Consequently, Mullainathan (cited in The World Bank, 2015) thinks that the poor exhibit the same

basic weaknesses and biases as all people do, except that in poverty, with its narrow margins for error,

the same behaviours often manifest themselves in more pronounced ways and can lead to worse

outcomes.

The debate is still on-going, as other authors focused their research on the effects of poverty on

individual’s mental models and mental frames. Frames are the lens through which individuals

understand “how the world works” (The World Bank, 2015), focusing on certain elements of reality,

while unconsciously ignoring or minimising others. Frames are developed based on prior experiences

and observational learning and they give meaning to our life experiences. Here we must mention the

names of Appadurai (2004), Ray (2012) and Duflo (2012), their studies supporting the idea that

poverty induced mental framing might prevent the poor from taking advantage of economic

opportunities, through a deficit of aspirations (The World Bank, 2015).

Guyon and Huillery (The World Bank, 2015; Guyon & Huillery, 2014) experimentally

demonstrated that mental models shape our acting and people from disadvantaged groups tend to

underestimate their abilities and even underperform in group context, if they are reminded of their

vulnerable status. Their data show that poor students have lower academic and employment aspirations

than wealthier students at a comparable level of academic achievement.

The Case of Romania

Our study builds on the idea of poverty generated mindset and aspirations deficit. Using data offered

by the World Values Survey (2012) for Romania, we analyse the differences in perceptions and values,

of both the most affluent and the least affluent.

The particular focus is concentrated on perceived life satisfaction, control over life course, attitude

towards work, social and communitarian involvement, openness towards novelty and risk taking.

The Data

The data was collected during October – December 2012.

The sample size for the Romanian survey consists of 1503 respondents, with an estimated error of 2.6.

The sample was obtained through the selection of voting precincts within stratum. Selection type:

probability proportional to size, where size is the number of registered adults.

Survey procedure:Face-to-face, computer-assisted, respondent reading questionnaire.

For the aim of our study, we made a selection of respondents from the main survey sample, based on

their income level. We selected the lower income step group, consisting of 171 respondents. We also

selected the respondents from the three upper steps of income groups (eights step, ninth step and tenth

step). We chose to select the three upper steps in order to balance the dimensions of our two

comparison groups. Thus, the respondents of the three upper income steps of the Romanian World

Values Survey Sample make the upper income group of our research (see Table

The Results

If the responses to certain survey questions were distributed on scales with more than two steps, we

dichotomized them, in order to better emphasize the adherence of respondents to the two main

tendencies.

Rich and poor – the common ground

People of the two groups share the belief of being in control over their life and largely having

freedom of choice (see Fig.

significantly restraining people’s margins for error, people assume their control over life choices, thus

their responsibility of the outcome. This result is interesting considering the poverty induced mental

framing theory that builds on the idea of poor people’s lack of trust in their ability to change their

future and aspirations deficit.

The two groups share the belief that hard work is the instrument of achieving a better life, rather

than luck or other factors (see Fig.

group believe they can improve their quality of life through their own efforts, the survey answers

contradicting the idea of learned helplessness associated to poverty.

All the graphs in this material respect the same legend as presented in Fig.

The two groups adhere to the positive value of competition, considering that it motivates people to

work harder and develop new productive ideas (see Fig.

belief in personal effort to escape poverty, rather than fatalism.

Personal contribution to the social and communitarian benefit is greatly valued both by the members

of the affluent group and by the people of the lower income group (see Fig.

of the poor as passive recipients of social aid, assigning themselves in passive roles, yet they seem to

endorse the principle of personal contribution and participation.

Both groups positively value creativity and creation of novelty. Considering the limitations and

difficult trade-offs that poor people face in their everyday lives, it is possible that finding creative

answers to their problems might be an important survival tool. Yet, this response cannot be generalised

as an indicator to their openness to novelty, as answers to other questions seem to suggest less

openness to scientific novelties and less acceptance for the positive role of scientific discoveries in the

economy and society.

Rich and poor – the main differences:

The analysed data is in line to a vast volume of research results, demonstrating the negative

correlation between poverty and happiness (see Fig.

positive affect, rather than a general evaluation of the quality of life, better reflected in the concept of

life satisfaction. In fact, the most significant difference between the two groups stands in their self-

perceived happiness and general life evaluation.

As expected, most individuals of the affluent group are rather satisfied with their life, while more

than half of the lower income group are dissatisfied with their life. Yet, we should mention that almost

half of those in the low income group evaluate their life on a positive note (see Fig.

happiness has found that income is a better correlate of life evaluation (satisfaction) than emotional

wellbeing (Kahneman & Deaton, 2010). Yet, in this survey, the people of the lower income group are

more inclined to assess themselves as unhappy, while life dissatisfaction comprises a more nuanced evaluation.

The role of the state is assessed differently by the two groups – the lower income group considers

that the state must be a “provider” for its citizens, taking care of the poor, a view that is supported by a

much smaller fraction of the affluent group (Fig. 8). Another interesting observation is that the lower

income group is more inclined to respecting authority (the rulers), even in the form of obedience.

People of the affluent group are opened to the novelties of science to a greater extent. This is

relevant from the perspective of people’s openness to new opportunities, new tools for improving the

quality of life and for economic success. On the contrary, the lower income group manifests reticence

for the novelties of science, perceiving science more as a threat than as an economic development tool

(Fig. 9). This is also correlated with a stronger adherence to traditional values and less tolerance for

differences, whether religious, ethnical, etc.

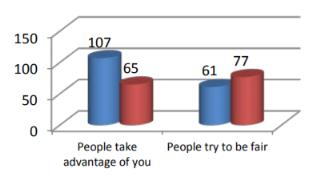

Samson & Kostyszyn (2015) focused their research on the trusting behaviour and their experimental data supported the idea of cognitive overload negative effect on trust. This approach offers one possible explanation for our results, correlated to the Mullainathan and Shafir’s (2013; 2014) theory of the cognitively demanding context of poverty. As Fig.

to believe that others would take advantage of them, if given the chance.

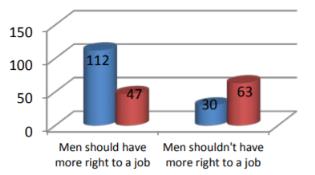

The scientific literature (Duflo, 2012) clearly shows that women empowerment and economic development are closely related, and economic development alone can play a major role in reducing inequality between men and women, women’s empowerment usually following naturally when people don’t face the difficult trade-offs imposed by poverty (The World Bank, 2011). The data of this survey validates the idea that poverty fosters gender inequality (see Fig.

Conclusions

As the World Bank Report of 2015 (The World Bank, 2015) demonstrates, policy makers,

development experts, researchers and other stakeholders have their own mental models that filter the

reality of poverty. Common views highlight the differences between the poor and the non-poor,

supporting the idea of a specific “culture of poverty”. But are the poor “… a different kind of people”

that “...think and feel differently” (Krishna, 2011). Could we agree that „poverty, insecurity, and

ignorance do not produce as ‘decent’ people as do wealth, security, and knowledge”? (Krishna, 2011)

Recent research rejects these ideas, explaining the poverty perpetuating behaviour sometimes

exhibited by the poor as a consequence of the cognitive taxation imposed by scarcity. Other researchers

do, however, emphasize the fact that poverty is associated to specific mental models and frames

through which people give meaning to their life experiences, developed as a result of social learning

and past events.

Using data offered by the World Values Survey (2012) for Romania, we explored (in a comparative

manner) the beliefs and values expressed by the most affluent and the least affluent individuals of this

nationally representative sample.

Some of the results are supported by the scientific literature. The poor are more inclined to assess

themselves as unhappy and to be less satisfied with life (a large body of literature validates the negative

correlation between income and happiness). They manifest beliefs that support a less trusting behaviour

and less tolerance for differences, whether religious or ethnical, etc. Their beliefs rather support gender

inequalities. They are less opened to the novelties of science and they perceive science more as a threat

than as an economic development tool.

On the other hand, although poverty imposes a multitude of limitations and barriers, the poor

assume control over life choices. They believe that hard work is the instrument of achieving a better

life, rather than luck or other factors, thus believing in their empowerment through their own efforts.

Doing good for the society is also greatly valued by the people of the less affluent group, suggesting

their desire to communitarian and social activism. This is a rather surprising result, considering the

theories of learned helplessness associated to the poor, perceived as passive recipients of social aid.

This was an exploratory exercise, focusing on the trends that were easily identifiable in the data, but

further analysis based on a more complex statistical approach is necessary, as it might obtain more

nuanced results.

References

- Samson, A. (2015). The Behavioural Economics Guide 2015, pp. 1 available at: https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/the-behavioral-economics-guide-2015/

- The World Bank (2015). Mind, Society and Behavior, World Development Report, available at: http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/Publications/WDR/WDR%202015/WDR-2015-Full-Report.pdf

- Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2013). Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much. New York, NY: Time Books, Henry Holt & Company LLC.

- Lewis, O. (1966). The Culture of Poverty. Scientific American, 215(4).

- Ryan, W. (1976). Blaming the Victim Revised Edition. New York: Random House Inc.

- Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2014). Scarcity: The New Science of Having Less and How It Defines Our Lives. London: Picador.

- Mani, A., et al, (2013). Poverty Impedes Cognitive Function. Science, 341(976).

- Guyon, N., & Huillery, E. (2014). The Aspiration-Poverty Trap: Why do Students from Low Social Background Limit their Ambition? Evidence from France, available at: https://www.unamur.be/en/eco/eeco/paper_autocensure_feb2014.pdf

- Appadurai, A. (2004). The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the Terms of Recognition. In Rao, V. and Walton, M., (eds.) Culture and Public Action, Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, California, pp. 59-84.

- Ray, D. (2002). Aspirations, Poverty and Economic Change, available at: https://www.nyu.edu/econ/user/debraj/Courses/Readings/povasp01.pdf

- Duflo, E. (2012). Women Empowerment and Economic Development. Journal of Economic Literature, 50(4), 1051–1079.

- Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 107(38), 16489-93.

- Samson, K., & Kostyszyn, P. (2015). Effects of Cognitive Load on Trusting Behavior – An Experiment Using the Trust Game. PLoS ONE 10(5): e0127680.

- The World Bank (2011). Conflict, Security and Development, World Development Report, available at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWDRS/Resources/WDR2011_Full_Text.pdf

- Krishna, A. (2011). One Illness Away: Why People Become Poor and How They Escape Poverty. UK: Oxford University Press.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

04 October 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-014-3

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

15

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1115

Subjects

Communication, communication studies, social interaction, moral purpose of education, social purpose of education

Cite this article as:

Cojanu, S., Stroe, C., & Militaru, E. (2016). A Behavioural Economics Approach to Poverty - the Case of Romania. In A. Sandu, T. Ciulei, & A. Frunza (Eds.), Logos Universality Mentality Education Novelty, vol 15. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 223-230). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.09.29