Abstract

The practical value of English used in business engineering relates to the mastery of language resources that can be achieved by professionals (and students) in business administration, management, economics, PR, advertising and marketing, since language is produced by thought and produces it, thus, creating and modifying reality. Communication strategies are universal, transferable and, sometimes, inter-changeable, therefore all participants in the global dialogue can benefit from the communication competence of specialists and entrepreneurs, consequently increasing the efficiency of exchanging business ideas. On the other hand, we all are consumers of goods and services (produced and provided by business), and many people are also either stakeholders or investors; therefore, knowing the specifics of language and communication in business will help everyone understand the deeper inner meaning implied in socio-economic, corporate and advertising discourses, so as to identify the manipulative mechanisms and techniques influencing public opinion. Argumentative and persuasive linguistic potentials create a positive corporate image and improve company and product positioning in the public consciousness, with potentially increased numbers of customers and shareholders.

Keywords: Universal strategiesentrepreneur communicationEnglish in business engineering

Introduction

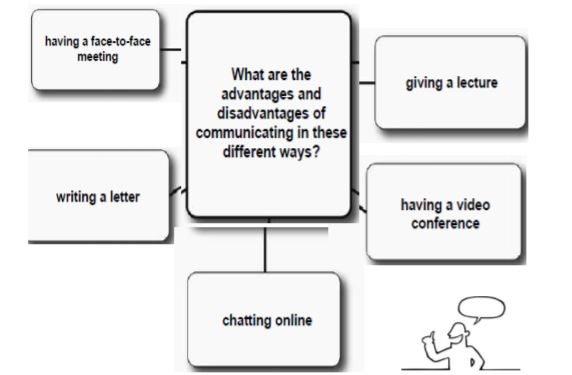

Various aspects of intercultural business discourse and business communication in the national

tongues are analyzed nowadays so as to: design the theoretical model of intercultural business

communication; compare countries in point of business communication; suggest discursive strategies

for multicultural business meetings; propose dialogue models for multicultural workplaces with tips for

communicating with representatives of European, Asian and other cultures; explore intercultural

communication worldwide (Amernic & Craig, 2006, p. 182).

Language is a vital factor in multinational management (Bargiela-Chiappini, 1997, p. 157) and

complex ranges of business discourse issues need to be acquired. Business communication is studied

by combining descriptive and prescriptive targets so as to better understand its mechanisms, and

provide students and business people with the means of effective communication (including skills in

foreign languages).

In studying the specific business engineering language in tertiary education, learners need a shift

from simulated data to naturally-occurring corporate idioms (Bargiela-Chiappini & Nickerson, 2007, p.

165). Acquisition of business lexis, functional pragmatics of intercultural business communication,

cognitive models of business discourse, and analysis of customary economic discourse in intercultural

teams and corporations constitute the focus in current teaching by professors at academic levels of

education.

New literacies

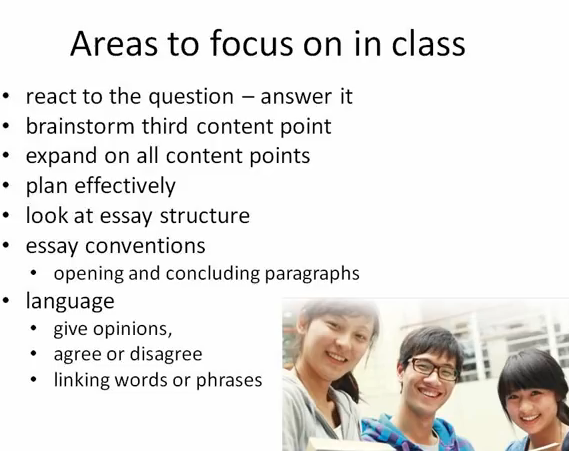

The advent of IT has presented professors of all languages and subjects with both challenges and

opportunities relating to new forms of information, graphic, visual and media literacies, and how to

integrate these with more traditional forms of literacy teaching activities.

Similarly, the invading internet communication (particularly the social media) has triggered (Cismas

et al, 2015a, p.78) an explosion of new and different interactive text-types as well as written genres.

The situation today is radically different from the one few decades ago, with people constantly com-

municating in writing through a whole range of interactive platforms. This writing revolution can be

exploited by professors in seminars in order to raise awareness on critical aspects such as register,

appropriacy, dialogic achievement, conveying messages, informational and communicative context &

content, differences in formats and organisation, and discrepancies between the spoken and the written

language (Cismas et al, 2015b, p.134).

It’s not just new literacies that represent and opportunity and challenge – it’s new text-types/genres

too:

E-mail

Texting

Blogging

Tweeting

Posting

Instant messaging

etc. …

A veritable Writing revolution: all purposeful text-types/ audiences/ contexts teens will engage with

in real life.

Communication strategies are employed by learners when their own linguistic competence in the target idiom is insufficient. It includes making themselves understood in the foreign language and

having others help them understand if necessary. Students use communication strategies (Cismas et al,

2015c) to offset any inadequacies they have in grammatical ability and, particularly, in vocabulary.

Communication strategies aid learners with participating in and maintaining the flow of ideas and in

improving the quality of communication.

This, in turn, enables them to have increased exposure and opportunities to use the target idiom,

leading to more chances to test their assumptions about it and to receive feedback. Without such

strategies, learners will avoid foreign language risk-taking as well as specific topics or situations.

Universal strategies for foreign language communication in writing

Language strategies are defined as particular actions, behaviours and thought processes that learners

consciously use to enhance their own communicative competence and language learning outcomes

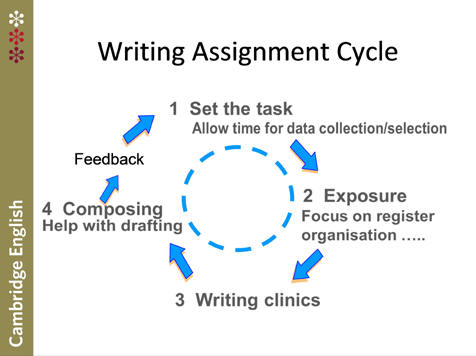

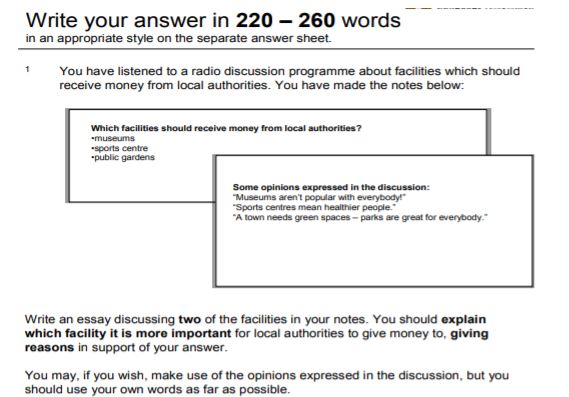

(Cismas et al, 2015d). Seminar work for better writing skills in business engineering focuses on outlining

processes leading to the assembly of adequate documents in the corporate formats required today.

Students manage document drafting according to the cycle in the figure below, improving their skills in

relation to the broad criteria achievement categories of content, communicative achievement, organisation

and language (Campbell, 2006, p. 101).

When writing, L2 learners need guidance with every step of the process:

Data collection

Selecting

Planning

Draftin

Crafting

Editing

Rewriting

Proof-reading.

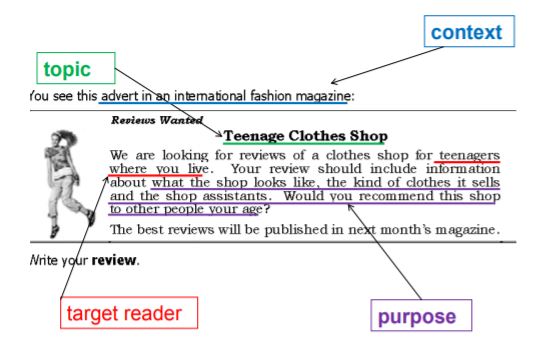

Any assignment cycle needs to begin with the clear setting of and exploring the dimensions of the

task (Firth, 1995, p. 326). There are numerous aspects to consider: learners’ level of familiarity with

the communicative context of the task and their awareness of typical functional content implied by it.

Test writing tasks request a clear text-type: letter, e-mail, review, essay, story, article, and a clear

communication context.

Learners need to be kept focused on the task. Many students, even tertiary-level ones, at any

proficiency level, do not seem to have individual viewpoints or questioning minds when interacting in

the target idiom. Generally, they do not appear to be inquisitive, but, instead, they are rather passive,

lacking enthusiasm, so they rarely ask (Gotti, 2005, p. 397) for clarification or confirmation in artificial

teaching settings.

However, this aspect may be explained by the fact that academic language teaching and learning

will always encourage individual competition, so competitive students who want to reach their goals

effectively may prefer the types of communication strategies that allow them to think and work alone

rather than collaborate with others, especially in cultures (Hagen, 1993, p. 124) where team-work is

unfair or less productive.

context

The use of accuracy-oriented strategies for writing activities means that students focus on correct use of English, seeking to improve grammar accuracy by self-correcting the mistakes. A comparison among the number of words students produce, the number of grammar mistakes, and the number of attempts at self-correction in learners’ responses to the problem-solving written tasks reveals that the high-ability students employ this type of strategy more than their low-ability counterparts.

Grammar mistakes are rare for high-ability learners (less than one per 100 words). All mistakes they make in their drafts are corrected as soon as they are noticed. In contrast, low-ability students do not sense their own errors. High-ability students self-correct more than those at a low ability level.

All in all, a high use of accuracy-oriented strategies reflects the ability to notice and correct language mistakes, positive attitudes towards mistakes, and the ability to monitor the production of language.

Universal strategies for foreign language oral communication

Practical advice and speaking language tasks should be provided in seminars for business engineering professionals and entrepreneurs. When students face communicative problems, they will use nonverbal language to express themselves, implementing gestures, facial expressions, and eye contact to give hints. As nonverbal strategies are behaviour aids to the verbal output, content analysis cannot be used.

Less competent speakers rely heavily on paralinguistic knowledge.

Cultural values influence the choice of communication strategies as certain cultures consider too many gestures as impolite. In other cultures, younger people are considered rude if they wave hands to signal denial or refusal: such things are supposed to be expressed verbally, by yes/no. Help-seeking strategies occur in situations where speakers try to solve communicative problems by asking for assistance directly or indirectly. Not only may they ask for repetition, clarification, and confirmation,

but they may also use rising intonation or pauses to signal a need for help form their partners

The speech may not be perfect, the interlocutors may not know every single word or concept used in

communication, but strategies to compensate for such difficulties need to be acquired, and speakers

must be armed with a plan for what they are going to say to help in this situation.

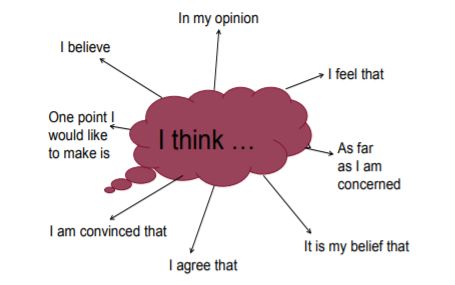

A brief list of universal strategies (Koester, 2004, p. 76) used in foreign language communication

includes:

When the exact word does not come to mind use general lexis or examples of items in that concept category.

Build relative sentences to provide a description of the object (a person who ... / thing that ... / place where...).

Describe the purpose or function the object has (It’s used to + infinitive / for + -ing).

Use synonyms or antonyms. This strategy works well with adjectives.

Employ approximations (It’s a kind of ... / It’s a sort of ...).

Use expressions to give your opinion and ask for your interlocutor’s opinion.

Agreeing, disagreeing and partly agreeing. It is a good idea to justify your opinions (explain your

reasons).

Show that you are interested in what your partner is saying and ask for clarification if necessary.

Make suggestions and/or respond to them: why don’t we ... (+ verb without ‘to’)? Shall we ... (+

verb without ‘to’)? Would you like to ... (+ verb)? Let’s ... (+ verb without ‘to’) What/How about ... (+ -ing)?

Take turns with your interlocutors because you all need to participate in the discussion.

Use example to illustrate your ideas and get your message across.

Avoid silence and play for time to get some moments for putting your ideas together. In English-

speaking cultures long silences or pauses are avoided. By looking at the interlocutor(s) one shows

that s/he is listening and indicates the wish to speak or use expressions to keep their turn.

Use gestures and body language that can assist the communication (mime, nod, keep eye contact).

Combine communication strategies and lexical developmentto overcome limits of idiom

reception/production.

Activities to combine strategy practice with vocabulary development.

In many spoken encounters, like workplace activities or everyday situations, English language

learners often face unfamiliar words and phrases that inhibit comprehension. Some other times they

experience situations where their English language limits prevent them from expressing messages

effectively or accurately. Electronic dictionaries, with their ubiquity, ease and speed of use, have

become an easy remedy to this problem. However, by relying on such tools speakers do not really

improve their communicative competence, but rather deny themselves the opportunities to put their

language to use.

Conclusion

Teaching communication strategies is an effective way to improve students' dialogic competence. It

is also a practical way of preventing them from over-relying on exterior means during communicative

activities. Strategy practice can readily be combined with activities to aid the development of students’

lexis. Learners are then provided not only with tools to communicate effectively, but also with

opportunities to expand their vocabulary; at the same they will become proficient in using dialogue

strategies for business engineering goals.

References

- Amernic, J., & Craig, R. (2006). CEO-speech: the language of corporate leadership. Montréal, McGill: Queen’s University Press.

- Bargiela-Chiappini, F. (1997). The languages of business: An international perspective. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Bargiela-Chiappini, F., Nickerson, C. (2007). Business Discourse. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Cismaş, S.C., Dona, I., Andreiasu, G.I. (2015a). CLIL Supporting Academic Education in Business Engineering Management. 11th WSEAS International Conference on Engineering Education EDU15 University of Salerno, Italy, June 27-29 2015, Re-cent Research in Engineering Education pp. 78-88 WSEAS – World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society www.wseas.org

- Cismaş, S.C., Dona, I., Andreiasu. G.I. (2015b). Tertiary Education via CLIL in Engineering and Management, 11th WSEAS International Conference on Engineering Education EDU15 Recent Research in Engineering Education Salerno University, Italy, June 27-29 2015 pp.134-142 WSEAS (World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society) www.wseas.org

- Cismaş, S.C., Dona, I., Andreiasu, G.I. (2015c). Teaching and Learning via CLIL in the Knowledge Society. 2nd International Conference on Communication and Education in Knowledge Society CESC2015 West University and the Institute for Social and Political Research, Timisoara, November 5-7 2015, Trivent Publishing House Budapest http://cesc2015.org http://trivent-publishing.eu

- Cismaş, S.C., Dona, I., Andreiasu, G.I. (2015d). Responsible leadership. SIM 2015: 13th International Symposium: Management During & After the Economic Crisis the Polytechnic University and West University of Timisoara, Romania, October 9-10 2015, Elsevier http://sim2015.org/ www.trivent.eu

- Campbell, K. (2006). Thinking and Interacting like a Leader. Chicago: Parlay Press.

- Firth, A. (1995). Studies of language in the workplace. Oxford, Pergamon.

- Gotti, M., Gillaerts, P. (eds.). (2005). Genre variation in business letters. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Hagen, S. (1993). Languages in European business: A regional survey of small and medium-sized companies. London: City Technology Colleges Trust Ltd.

- Koester, A. (2004). The language of work. London/New York, Routledge.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

04 October 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-014-3

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

15

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1115

Subjects

Communication, communication studies, social interaction, moral purpose of education, social purpose of education

Cite this article as:

Cismas, S. C. (2016). Universal Strategies in Foreign Language Communication. In A. Sandu, T. Ciulei, & A. Frunza (Eds.), Logos Universality Mentality Education Novelty, vol 15. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 215-222). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.09.28