Abstract

With growing geo-economic globalization, there is constant rise in the volume of international business contacts, and English for specific purposes, namely for business engineering, must be able to deal with these new challenges. Theories and practical methods of teaching and learning ‘foreign languages for career purposes’ have focused on business English as the lingua franca of international affairs. Business linguistics centres on idiom functioning in economy, and on the linguistic component of business communication. The methodology involves both traditional and modern teaching-testing methods for the discourse and for the emerging text, discourse analysis, conversation analysis, empirical, descriptive, comparative techniques, cognitive, pragmatic, and genrestyle analyses. All types of linguistic data are used as study materials – real or experimental, authentic or simulated, as well as their combinations. The current article reviews international English idiom testing strategies and their impact upon students’ learning approaches and their subsequent proficiency levels.

Keywords: Academic English testsstudents’ study stylesentrepreneur levelstradition and modernity in foreign language teaching

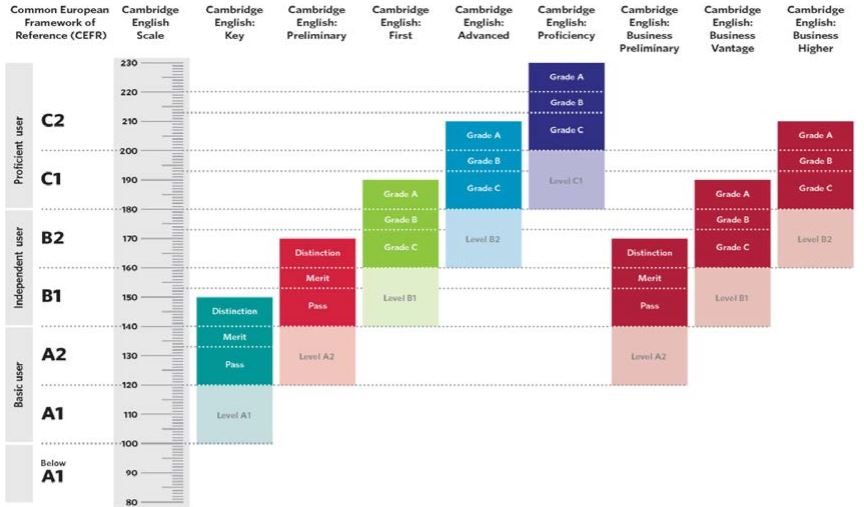

EU CEFR levels and Cambridge English Scale scores

The Cambridge English Scale is a range of scores used to report results for Cambridge English

exams. Such scores replace the candidate profile and the standardised scores. Grades and Common

European Framework of Reference for Languages – CEFR levels are retained. Scale scores make clear

exams alignment with each other, and with the CEFR.

Cambridge English First, First for Schools, Advanced and Proficiency have reported on the scale

since January 2015. Cambridge English Key, Key for Schools, Preliminary, Preliminary for Schools,

and the Business Certificates were added in February 2016. Candidates receive a Statement of Results

and a certificate containing the candidate’s score on the Cambridge English Scale for each of the four

skills (Reading, Writing, Listening and Speaking) and Use of English where tested, together with the

score on the Cambridge English Scale and the grade as well, in accordance with the CEFR level for the

global exam.

In addition, the certificate contains the level for the UK National Qualifications Framework – NQF.

The overall score is calculated by averaging the individual scores a candidate receives.

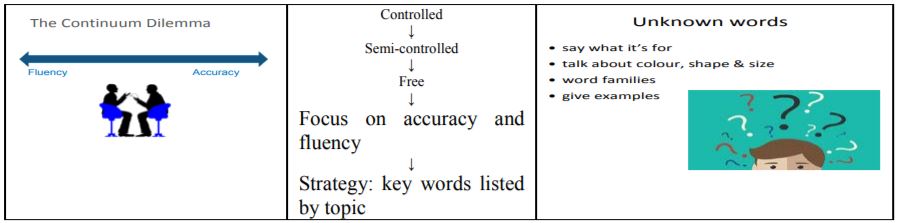

Many students appear to have problems communicating in English, especially the low ability ones. This may be caused by lack of basic grammar and vocabulary (Adler, 1983, p. 45) and by deficiency in using adequate communication strategies. Learners experience difficulty in selecting the most appropriate & effective strategies for business engineering communication tasks. The dialogic tactics they implement can form an inventory of elicited answers related to academic levels and job communication strategies in use. Low-ability students resort to risk-avoidance means, especially time-gaining strategies, and need assistance in developing risk-taking techniques: social-affective, fluency-oriented, help-seeking, or circumlocution.

Relating scores between exams

The Cambridge English Scale represents performance across a wider range of language ability than any single exam. Each exam is mapped to a section of the scale; despite exams being targeted at specific levels, there is a degree of overlap between tests at adjacent levels, and the new Cambridge English Scale shows where the exams overlap and how performance on one exam relates to performance on another.

Candidates who achieve the same Cambridge English Scale score in different exams show comparable levels of ability. For instance, a test taker with 182 in Cambridge English First gets a similar score in Cambridge English Advanced. Exam alignment is an integral part of test construction procedures as well as of the rating scales used to assess performance.

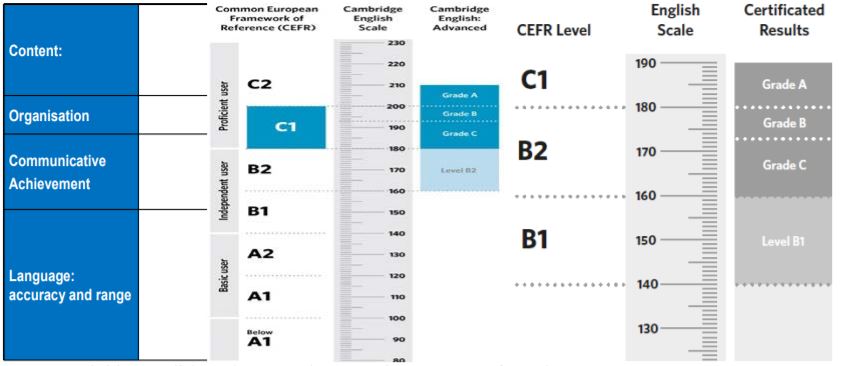

The example below shows the link between CEFR levels, the Cambridge English Scale and the grades in Cambridge English Advanced: a candidate with 200-210 gets grade A and a Cambridge English Advanced Certificate stating Level C2. The maximum achievable score in Cambridge English Advanced is 210. The ones with 193-199 get grade B. Those with 180-192 obtain grade C. All these candidates get Level C1 Cambridge English Advance Certificate. The ones with 160-179 get Level B2 and those with 142-159 do not get certificates but are given a Cambridge English Scale score shown on the Statement of Results, as illustrated in Fig.

The Business English Certificate Vantage (BEC Vantage) assesses the English used in business context at CEFR B2. Grade A candidates achieving 180-190 receive BEC Vantage stating their Level C1 skills.

Grade B or Grade C ones (160-179) get Level B2.

Those below Level B2, but within 140-159, get Level B1. BEC Vantage candidates with 122-139 do

not get a result, CEFR level or certificate, as scores under 122 are not reported in BEC Vantage.

Speaking skills in tests and in daily business engineering communication

The interest in communication strategies has grown over the last decades. Initially, this subject was

introduced as a new area of applied linguistics, and the papers published on inter-language first

mentioned the concept of communication strategies in English. Such strategies are systematic

communication-enhancing de-vices used to handle difficulties in message exchanges, thus preventing

communication from breaking down or turning vague. The range of dialogue strategies focus on the

interaction process, and on the problem-solving acts arising from the gaps in the speakers’ linguistic

assets.

Communication strategies in business engineering are, in fact, particular problem-solving skills

(Argenti, 2008, p. 213). The act of merely uttering expressions in an attempt to communicate in

English for professional purposes is not strategy. However, if students have problems in using a

particular word in the target idiom, the notion of strategy emerges. Hence, they use description or

circumlocution instead of the problematic word, or even resort to gestures so as to reach the

communication goal.

In this way, a strategy is a possible means of problem-solving that the users select because it works

effectively and they are comfortable with it. Such strategies envisage awareness and problem-

orientedness. They target message achievement or compensation (used by good language learners) and

reduction or avoidance (low ability ones). Apart from these, risk-taking or risk-avoidance strategies are

adopted, taking into account tolerance of risk as one of the influences that makes individual students

vary. Under certain circumstances, they are encouraged not to ‘lose face’ as a result of making

mistakes, so they are likely to employ risk-avoidance strategies to maintain the conversation. In

contrast, other students might have been raised in an environment where people communicate naturally

without seriously worrying about correctness, and they are more likely to take risks for expanding their

resources in order to solve communication breakdowns.

Considering the communication strategies implemented, business engineering university students

most frequently use approximation (Cismas et al, 2015a, p. 78), paraphrasing and circumlocution.

Taxonomies of communication strategies have generally been based on criteria such as whether the

target group chooses to achieve or reduce the goal, or whether they consult sources of information in

their native tongue or in the target idiom.

The risk-taking strategies expand linguistic resources and meet the dialogue goals. They include:

social-affective strategies for dealing with emotions or attitudes; fluency-oriented strategies, for speech

clarity and pronunciation; accuracy-oriented strategies, for paying attention to forms of speech; non-

verbal strategies, such as giving hints by using gestures and facial expression; help-seeking strategies,

such as asking for repetition, clarification or confirmation; and circumlocution strategies, for

paraphrasing or describing objects properties.

The risk-avoidance strategies are what speakers use to adjust the message to their linguistic

resources: message abandonment strategies, for leaving a message unfinished; message reduction or

alteration strategies, to allow the substitution of familiar words; time-gaining strategies (gambits or

fillers) to keep the communication channel open and maintain discourse flow in difficult moments

(Cismas et al, 2015b, p. 142).

In the relationship between the means and the ends of communication, the ideal context assumes

that speakers’ linguistic resources and the message are in balance, i.e. speakers have sufficient

linguistic skills to express the message. However, some speakers wish to convey a message beyond

their capabilities, so they have two options: either attempt to increase their resources to reach the

communicative goals, although it is risky to do so (the risk-taking strategies), or to tailor the message to

the available resources (the risk-avoidance strategies, defined as such because there is no risk to take,

since the speakers may simply leave the message un-finished). Oral communication is more successful

if the interlocutors are homogeneous in point of nationality, knowledge background, age and similar

cultural and educational backgrounds (Cismas et al, 2015c).

There are few studies investigating mixed-ability idiom learners and their employment. The focus is

on the link between communication strategies and adjacent variables, like interaction with native

speakers or frequency of using the communication strategies. This basic feature of interacting and

responding appropriately is often overlooked in teaching materials, and dialogue facilitators must be

used in business engineering tasks.

Certain speakers of English as a foreign idiom communicate well by uttering few words while

others have difficulty in getting the same results. The former may use communication strategies

(gestures, imitating sounds/movements, paraphrasing, and deriving new words). Poor selection of

strategies for accomplishing the language tasks will lead to unsuccessful communication, mainly in

lower-ability students who lack basic lexis or grammar. They will expand short answers, continue

stories, or show that they understood the idea so far.

In both international and national contexts, students with low language abilities employ

communication strategies, but they still are not successful in conveying their message; hence analysing

dialogue skills is worth-while. Thus, language professors potentially see how high-ability students

differ from low-ability ones in using such approaches and in taking roles in conversation. Practically,

professors apply the strategies in the speaking tasks inventory to elicit students’ responses. It might be

effective if the didactic staff members realized which types of skills students tend to use before

planning lessons, selecting materials, and opting for teaching methods.

Conclusions

High-ability students prefer risk-taking strategies, such as social-affective, fluency-oriented, help-

seeking, and circumlocution, whereas the low-ability ones tend to employ more risk-avoidance

strategies, like time-gaining. The reason may be that high-ability students implement most of the risk-

taking strategies as a result of their proficiency in English. Additionally, with their higher degree of

cognitive flexibility, they are likely to apply social-affective strategies to manage their feelings during

communication.

In contrast, the low-ability students’ limited English proficiency may lead them to use risk-

avoidance strategies, and play for time. Less competent speakers rely more on their lexical acquisitions

than on linguistic knowledge (Cismas et al, 2015d). The communication strategies employed by the

high-ability students make them more successful in oral communication. Their risk-taking is more

effective in conveying meaning or concepts since all information is provided in a clear and direct way (Cismas et al, 2015e).

Communication strategies should be taught for business engineering in academic environments

because students benefit not only from the linguistic knowledge but also from the communication

strategies which they will use to promote effective language learning (Gouveia, 2004, p. 68). Often

poor learners cannot understand how the good ones obtain their solutions and feel unable to perform

like the good ones. After revealing the process, the myth fades.

In addition, if students do not select strategies in the service of their intended tasks, skills, and goals,

they might not easily find the most appropriate means and be successful. Hence, enhanced

effectiveness is obtained if both process and product are integrated in the teaching methods.

Consequently (Nelson, 2006), strategic competence and language-skills development will be supported

by a learning system in which students can foster their ability to select appropriate strategies.

References

- Adler, R. (1983). Communicating at work: principles and practices for business. New York: Random House.

- Argenti, P.A. (2008). Corporate communication. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Cismaş, S.C., Dona, I. & Andreiasu, G. (2015a). CLIL Supporting Academic Education in Business Engineering Management. 11th WSEAS International Conference on Engineering Education EDU15 University of Salerno, Italy, June 27-29 2015, Re-cent Research in Engineering Education pp. 78-88 WSEAS-World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society www.wseas.org

- Cismaş, S.C., Dona, I., Andreiasu, G. (2015b). Tertiary Education via CLIL in Engineering and Management. 11th WSEAS Inter-national Conference on Engineering Education p.134-142 www.wseas.org

- Cismaş, S.C., Dona, I., Andreiasu, G. (2015c). Teaching & Learning via CLIL in the Knowledge Society. 2nd International Conference on Communication and Education in Knowledge Society CESC2015 West University of Timişoara, Institute for Social Political Research, Timisoara, November 5-7 2015, Trivent Publishing http://cesc2015.org http://trivent-publishing.eu

- Cismaş, S.C, Dona, I., Andreiasu, G. (2015d). E-learning for Cultivating Entrepreneur Skills in Business Engineering. 2nd International Conference on Communication & Education in Knowledge Society CESC2015, Trivent Publishing http://cesc2015.org http://trivent-publishing.eu

- Cismaş, S.C., Dona, I., Andreiasu, G. (2015e). Responsible leadership. SIM 2015-13th International Symposium: Management During and After the Economic Crisis, Polytechnic & West Universities Timisoara, October 9 2015, Elsevier http://sim2015.org

- Gouveia, C. (2004). Discourse, communication & enterprise. Lisbon: CEAUL, Lisbon University.

- Nelson, M. (2006). Semantic associations in Business English. ESP Journal, 25(2), 217-234.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

04 October 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-014-3

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

15

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1115

Subjects

Communication, communication studies, social interaction, moral purpose of education, social purpose of education

Cite this article as:

Cismas, S. C. (2016). Novelties in Academic English Testing. In A. Sandu, T. Ciulei, & A. Frunza (Eds.), Logos Universality Mentality Education Novelty, vol 15. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 208-214). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.09.27