Strategic Fit and Supply Chain Performance (SCP): The Effect of Supply Chain Management (SCM) as The Mediator

Abstract

Based on previous research, strategic fit among behavioural orientations can generate the behavioural planned to ensure the viability and performance of the firm. It is also mentioned before that behavioural orientation can also support company in increasing the supply chain performance. However, although behavioural orientation gives positive impact to SCP, companies are still challenged with issues such as, distortion of information, collaborative behaviours and many more that need to be managed well. To handle such issues, several authors recognized supply chain management (SCM) as a way that can mediate the relationship to improve performance. SCM enables seeks synchronization of intrafirm and interfirm operational and strategic capabilities into a unified, compelling marketplace force, and focuses supply chain partners on creating customer value. The importance of SCM as mediator should be considered as an important element to increase performance. Therefore, this study tries to theoretically investigate the potential benefits of SCM as a mediator to SCP. Also, it further explores the relationship of strategic fit between market orientation (MO) and supply chain orientation (SCO) to SCP. To investigate this relationship, this study proposes the covariance approach. The relationship and the covariance approach can be empirically tested for future research.

Keywords: Market OrientationSupply Chain OrientationSupply Chain ManagementSupply Chain PerformanceStrategic Alignment

Introduction

Competition in today’s business environment forces organizations to enhance their productivity and competitive advantage. In addition, companies must aware that competition today is not merely between organizations, but it involves the entire supply chain. How their supply chain performed will reflect their business performance. Therefore, SCP has been recognized as one of the critical factor that could help companies not only as a source of cost reduction but also as a source to gain competitive advantage (Deshpande 2012). This is potential to drive performance improvement in customer service, asset utilization, profit generation, and cost reduction.

Improving SCP needs a good understanding and commitment among all of the supply chain members. This is challenging since a supply chain, faces uncertainties from the market (customer) and the supply chain itself (Boon-Itt & Paul, 2008). The uncertainties then often lead to the distortion of the market information that will lead to phenomena termed bullwhip effect (Wisner, Tan & Leong, 2012). The Bullwhip Effect is defined as the “demand distortion” as it moves upstream in the supply chain due to the inconsistency of orders which may be bigger than that of sales (Lee, Kwon & Severance, 2007). The bullwhip effect will have adverse effects to the companies in the supply chain. For example, a manufacturer that only notices its immediate order will be misled by the bigger demand. Huge addition in cost will be incurred due to unplanned purchase of raw materials, improper capacity planning and utilization, inefficient over time, and additional transportation costs.

All of the above researches on behavioral impact on bullwhip effect in supply chain stimulate this study to understand further the impact of behavior. All of the above studies are being confined to lab experiments’ setting. A wider scope need to be observed. This study explores human behavior pattern that could explain the efficiency and effectiveness of a supply chain. Two behavioral aspects that gained researchers attention are the MO and SCO (Min et al., 2007; Matthyssens & Vandenbemp, 2008; Fewcett, Magnan & McCarter, 2008; Trkman et al., 2010; Whitten et al., 2012; Urde, Baumgarth & Merrilees, 2013). Understanding the effect of both on SCP could help to improve the bullwhip phenomena. The subsequent paragraphs will elaborate further the concepts of both market and supply chain orientations.

Mentzer (2001) defines SCO as a set of activities that need to be performed to realize the SCM philosophy. Companies that are supply chain oriented will manage the supply chain differently compared to those without SCO (Mentzer et al., 2001; Min & Mentzer, 2004; Min et al., 2007). This allows companies to disseminate information from the market throughout the supply chain.

However, besides SCO, companies need a specific capability that can be used to create superior customer value while gaining profits (Slater & Narver, 1994; Kohli & Jaworski 1990; Mentzer et al., 2001; Min et al., 2007). In the context of supply chain, MO has been observed to have the capability to improve the supply chain (Min et al., 2007).

In order to satisfy the customer, MO has been recommended by Kohli and Jaworski (1994) since it comprises “a set of company-wide implementing activities of the marketing concept so that market oriented firm, practices the three pillars of the marketing concept (customer focus, coordinated marketing, and profit orientation)”. Research shows that companies that are market oriented perform better than those that do not (Martin & Grbac, 2003; Lummus, Duclos & Vakurka, 2003). In addition, the model proposed by Juttner, Christopher, and Godsell (2010) shows that the components in MO influence SCP by decreasing supply chain cost, shorter lead time, and shorter end to end pipe line time.

Nevertheless, the SCO and MO could not directly affect the SCP. There must be a medium to mediate the relationship between the fit and SCP. Besides the uncertainties in demand and supplier relationship, performance will also be affected by the inefficiencies in SCM (Karami et al., 2015). SCM is important in term of the support from top management, information sharing, cooperation between department and other aspect of leadership (Hult, Ketchen, & Slater, 2004; Min et al., 2007; Karami et al., 2015). Therefore, SCM is no longer merely regarded as routine proses of delivering products but is more towards managing it in the right way so it could benefit the manufactures, stakeholders, and customers (Trkman, McCormack, Oliveira & Ladeira 2010; Stank et al., 2011; Wong, Boon-Itt & Wong, 2011). As a result, this study finds that it is important to affiliate SCM as the mediator to supply chain performance, which is also supported by Min et al. (2007), Deshpande (2012), and Karami et al. (2015).

SCM has been increasingly apparent with market globalization. According to Childerhouse and Towill, (2003), SCM is the management of material and information flows both in and between facilities, such as vendor, manufacturer, assembly plants, and distribution center. Based on this justification, this study finds that SCM is able to reach external information and accommodate the entire supply chain with sufficient information. This valuable information will then be useful to enhance SCP. Accordingly, some researchers find that SCM is a competitive element in the marketplace. It helps companies by reducing inventories and other costs and at the same time, more effectively meeting their customer demand.

The discussions in the previous paragraphs stimulate this study to enhance further on the impact strategic fit (MO & SCO) and SCM as a mediator to SCP. Although there are many researches in SCM, there are always different streams of research regarding the way that SCM is perceived. On top of that, there are still inconsistencies in how SCM is perceived especially between research and practice. Therefore a wider scope needs to be observed.

Problem Statement

The Mediation Effect

The existence of SCM (agreed on supply vision, shared information, shared risk, cooperation, integrating process, supply chain leadership, and long term relationship) as a mediator has been proven by Min et al. (2007). However, there are still inadequate discussions on how strong SCP is when it is mediated by SCM. This includes how SCP performs with and without SCM in the relationship. Providing answers to this ensures that practitioners will experience better management strategy in their supply chain process and could also reduce the risk of stock-out and backorder, while increasing customer satisfaction. This is supported by Green Jr. et al. (2013), Wong et al. (2012), Juttner et al. (2010), and Green and Patterson (2009).

Strategic fit between MO and SCO

In conjunction to the bullwhipped effect, as discussed in the introduction section, the uncertainty and bullwhip effect in turn results on poor control in the costing, on-time delivery, product quality, and customer satisfaction (Whitten et al., 2010; Stank et al., 2011; Deshpande, 2012). This phenomenon supports this study contention that MO must be supported by the SCO. The MO is an external orientation that is needed to improve the market understanding, while the SCO is an internal orientation that will improve supply chain relationship. SCO encourages companies to give special attention to the functional areas such as procurement, logistics, marketing, production, sale and distribution, which in return would also benefit the SCP (Green, McGaughey & Casey, 2006; Min et al., 2007; Tokman, Richey, Marino, & Weaver 2007; Juttner et al., 2010).

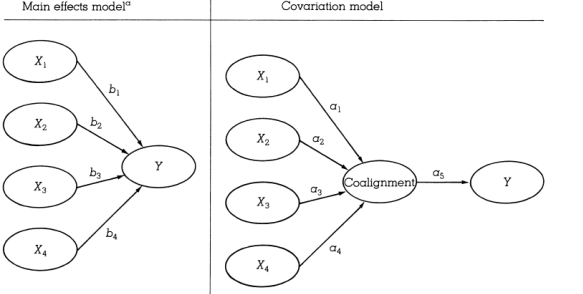

Therefore, this study proposes the alignment of MO and SCO. Studies regarding strategic fit especially on the alignment between MO and SCO is still lacking in the area of SCP (Sheperd & Gunter, 2011; Min et al., 2007). Different than Min et al. (2007) that views the relationship of SCO as a mediator between MO and SCM, this study contends that the two is better viewed as a synergistically to each other. In the statistical term they are covariance. Therefore this study chooses covariance between MO and SCO, in which the covariant is believed to lead to superior performance (Yu, Cadeaux, Song, 2012). The needs to study different approaches to analyze multiple strategic orientations are also suggested by Salavou, (2005) and Hakala, (2010).

Conceptual Framework

SCP is commonly understood as part of “an improved SCM” or “an effective SCM”. Deshpande (2012) defines it as the “multiple measures of performance developed by the organization to gauge the ability of a supply chain to meet an organization’s long-term and short-term objectives”. Others address that SCP is “the affective management among suppliers, materials, and customer in a supply chain (Johnson & Templer, 2011; Ou et al., 2010; Banomyong & Supatn, 2011; Beamon, 1999). The definitions even though are not exactly similar, support each other. Hence, with reference to those definitions, this study views SCP as a measuring tool to ensure that the process of delivering products is effective and efficient.

However, there are always difficulties in achieving performance. This study also finds that the difficulties in achieving SCP are also rooted from the internal SCP. The internal SCP measures and evaluates the effectiveness and efficiency of a function in producing its outputs and services. The results from this will reflect on cost, lead time, and reliability (Banomyong & Supatn, 2011; Mohamed Udin et al., 2006; Chan & Qi, 2003). It can even reflect certain external performance such as response rate on customer orders (Banomyong & Supatn, 2010; Mohamed Udin, 2006; Chan & Qi, 2003; Cooper et al., 1997; Lambert et al., 1998).

Accordingly, this study concludes that difficulties in improving SCP are also related to internal practices that relates to the behavioral orientation in the organization. Therefore, in order to improve performance, scholars believe that there is a need for strategic orientation in the organization. Strategic orientation improves SCP by establishing and embedding the behavioral values among the supply chain members. As a response to this, scholars suggested the injection of “fit”, which roots from the concept of “matching” and “aligning” into the system to improve the SCP results (Venkatraman, 1984; Schendel & Hofer, 1979). Fit requires practitioners to find the best strategic combination that is suitable to the situation.

The two behavioral orientation variables under analysis are the MO and SCO. It is hypothesized that the two needs to be aligned and any missing one or lacking in one will yield detrimental effects to a supply chain. The inclusion of the two variables is important since they provide the medium and environment that influence the relationship.

Researchers like Narver and Slater, (1990), Slater and Narver (1994), and Hunt and Morgan (1995) agree that MO provides a solid fundamental for sustainable competitive advantage for a company, which in turn will speed up the company performance. This is also explained by Hakala (2010), where a superior MO leads to a superior performance. Not only company performance, market-oriented companies will also experience efficient delivery, good inventory level, and efficient in demand planning (Boon-Itt & Paul, 2008).

This phenomenon supports this study contention that MO must be supported by SCO. The MO is an external orientation that is needed to improve the market understanding, while the SCO is an internal orientation that will improve supply chain relationship. SCO encourages companies to give special attention to the functional areas such as procurement, logistics, marketing, production, sale and distribution, which in return would also benefit the SCP (Min et al., 2007).

Therefore, this study proposes the alignment of MO and SCO. Studies regarding strategic fit especially on the alignment between MO and SCO is still lacking in the area of SCP (Sheperd & Gunter, 2011; Min et al., 2007). Different than Min et al. (2007) that views the relationship of SCO as a mediator between MO and SCM, this study contends that the two (MO and SCO) is better viewed as a synergy to each other. In the statistical term they are covariance. Therefore this study chooses covariance between MO and SCO, in which the covariant is believed to lead to a superior performance (Yu, Cadeaux & Song, 2012). The needs to study different approaches to analyze multiple strategic orientations are also suggested by Salavou (2005) and Hakala (2010).

Referring to the objective of this study, the SCO and MO could not directly affect the SCP. There must be a medium to mediate the relationship between the fit and SCP. As a result, this study finds that it is important to affiliate SCM as the mediator to SCP, which is also supported by Min et al. (2007) and Deshpande (2012). Again, based on the definition by Thomas and Griffin (1996), SCM manages to handle the information flows both in and between vendors, manufacturers, assembly plants, and distribution center. Also, SCM enables the integration of their operational activities with decisions and activities of their external business partners (Li & Wang, 2007). Therefore, the existence of SCM as the mediator between MO and SCO is crucially important for future research.

Therefore, this study sees the potential of foreseeing positive outcome when companies manage to overcome these difficulties by establishing SCM. SCM improves SCP by establishing a good information sharing and cooperation. On top of that, based on those issues, SCM enables companies or manufacturers to coordinate their decisions and activities to optimize their performance (Li & Wang, 2006).

Scholars (Mentzer et al., 2001; Chen, Paulraj & Lado, 2004) realize that SCM is not just a process but involves activities such as value creation, quality, and knowledge on the relationships within the supply chain. In addition, Green et al. (2006) also believe that SCM evolves into a body of knowledge focusing primarily on integration, customer satisfaction, and business results. Despite of many concepts in SCM, the similarity in SCM perspective has been clearly explained by Esper et al. (2010), that each concept highlights on coordination and collaboration with suppliers and customers. It also highlights the value of demand and supplies matching, and embraces a flow perspective.

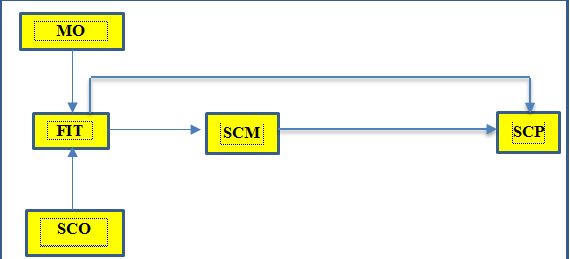

SCM is also important in terms of the support from top management, information sharing, cooperation between department and other aspects of leadership (Hult, Ketchen, & Slater, 2004; Min et al., 2007). Therefore, SCM is no longer merely regarded as a routine proses of delivering products but is more towards managing it in the right way so it could benefit the manufactures, stakeholders, and customers (Trkman, et al., 2010 and Wong et al., 2012). Therefore, this study concludes the discussion by establishing a conceptual framework that explains the above discussion.

Methodology

This study proposed that the data collected from the surveys, will be analyzed using SEM. SEM is an attempt to model the causal relationship between variables by including all the variables that are known to have some involvement in a study. SEM is a powerful multivariate analysis technique. When most multivariate analysis is for descriptive or exploratory research, SEM takes on a confirmatory approach that involves hypotheses testing. In the context of this research, SEM provides the researcher with the ability to model multiple mediating variables simultaneously.

SEM Terminology – when using SEM, the variables involved are termed differently. In such manner, the independent variables are referred to as exogenous, whereas the mediating variables are known as endogenous variables.

Fit as covariance

Constructing fit as a covariant is based on the basic principles of factor analysis. This explains that covariant among a set of indicators in terms of a smaller set of factors (first-order factors) and explaining the covariant among the first-order factors in terms of second-order factor. More specifically, fit as a covariant is specified as a higher order construct. The first and second-order factors signify the dimensions to be aligned. The whole network or path of relationships that has been discussed this far are schematically illustrated in Figure

Following Venkatraman (1989) alignment is specified as a second- order factor, where the first- order factors are the two dimensions that are to be aligned. The strategic alignment is an unobserved (latent) variable that cannot directly be measured and must be concluded from the observed variables (the two first order variables). MO and supply chain orientation SCO are measured by the indicator variables which are represented by the letter ‘Y’. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) together can be engaged to test the various hypothesized relationships collectively and simultaneously, and establish the goodness of fit of the model.

Conclusion

The main objective of this paper is to develop a conceptual model that could help future researchers to empirically discover the question of the effect of SCM as a mediator and the effect of strategic fit between MO and SCO to SCP. The paper first establishes the basis of the model by reviewing the important and fundamental issues in strategic fit. This includes the contents of the strategy and its basic structure. Through the application of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) the model is then established. The analytical framework could further help future research to explore or to venture in depth into the subject matter. Hence, it is suggested that an empirical study is conducted to validate the good fit of the theoretical model.

References

- Banomyong, R. & Supatn, N. (2011). Developing A Supply Chain Performance Tool For SMEs in Thailand. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 16(1), 20–31.

- Beamon, B.M. (1999). Measuring Supply Chain Performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 19 (3), 275-9.

- Boon-Itt, S., & Paul, H. (2008). Moderating Effects of Environmental Uncertainty on Supply Chain Integration and Product Quality: An Empirical Study of Thai Automotive Industry. Management Research News, 29(4), 200-209.

- Chen, I. J., Paulraj, A., & Lado, A. A. (2004). Strategic Purchasing, Supply Management, and Firm Performance. Journal of Operations Management, 22(5), 505–523.

- Chan, F.T.S. & Qi, H.J., (2003a). An Innovative Performance Measurement Method for Supply Chain Management. Supply Chain Management. International Journal, 8, 209–223.

- Childerhouse, P., & Towill, D. R. (2003). Simplified Material Flow Holds The Key To Supply Chain Integration. Omega, 31(1), 17-27.

- Deshpande, A. R. (2012). Supply Chain Management Dimensions, Supply Chain Performance and Organizational Performance: An integrated framework. International Journal of Business and Management, 7(8), 2.

- Esper, T. L., Clifford Defee, C., & Mentzer, J. T. (2010). A Framework of Supply Chain Orientation. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 21(2), 161-179.

- Fawcett, S. E., Magnan, G. M., & McCarter, M. W. (2008). Benefits, Barriers, and Bridges to Effective Supply Chain Management. An International Journal, 13(1), 35-48.

- Graca, S. S., Barry, J. M., & Doney, P. M. (2015). Performance Outcomes of Behavioral Attributes in Buyer-Supplier Relationships. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 30(7), 805-816.

- Green, K. W., McGaughey, R., & Casey, M. (2006). Does Supply Chain Management Strategy Mediate the Association Between Market Orientation and Organizational Performance? Supply Chain Management Journal, 11(5), 407-414.

- Gunasekaran, A., and Kobu, B. (2007), Performance Measures and Metrics in Logistics And Supply Chain Management: A Review Of Recent Literature (1995–2004) For Research And Applications. International Journal of Production Research, 45(12), 2819–2840

- Hakala, H. (2011), Strategic Orientations in Management Literature: Three Approaches To Understanding the Interaction Between Market, Technology, Entrepreneurial And Learning Orientations, International Journal Of Management Reviews, 13 (2), 199-217.

- Hult, G. T. M., Ketchen, D. J., & Slater, S. F. (2004). Information Processing, Knowledge Development, and Strategic Supply Chain Performance. Academy Of Management Journal, 47(2), 241-253.

- Hunt, S.D. And Morgan, R.M. (1995). The Comparative Advantage Theory of Competition. Journal of Marketing, 1–15.

- Ireland, R. D., & Webb, J. W. (2007). A Multi-Theoretic Perspective on Trust and Power In Strategic Supply Chains. Journal of Operations Management, 25(2), 482-497.

- Johnson,M., And Templar, S. (2011): The Relationship Between Supply Chain And Firm Performance. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistic Management, 41(2), 88-103.

- Ju¨Ttner, U., Christopher, M. & Godsell, J. (2010). A Strategic Framework for Integrating Marketing And Supply Chain Strategies. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 21(1), 104-12.

- Karami, M., Malekifar, S., Nasiri, A. B., Nasiri, M. B., Feili, H., & Khan, S. U. R. (2015). A Conceptual Model of The Relationship Between Market Orientation And Supply Chain Performance. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 34(2), 75-85.

- Kohli, A. K., & Jaworski, B. J. (1990). Market Orientation: The Construct, Research Propositions, and Managerial Implications. Journal of Marketing, 1, 1–18.

- Lambert, D.M. And Cooper, M.C., (2000). Issues in Supply Chain Management. Industrial Market Management, 29, 65–84.

- Lee, C.W., Kwon, I.W.G., And Severance, D. (2007). Relationship between Supply Chain Performance and Degree of Linkage Among Supplier, Internal Integration, And Customer. An International Journal, 12(6), 444-452

- Li, X., & Wang, Q. (2007). Coordination Mechanisms of Supply Chain Systems. European Journal of Operational Research, 179(1), 1-16.

- Lummus, R. R., Duclos, L. K., & Vokurka, R. J. (2003). Supply Chain Flexibility: Building a New Model. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 4(4), 1-13.

- Martin, J.H., Grbac, B., ( 2003). Using Supply Chain Management to Leverage A Firm’s Market Orientation. Industrial Marketing Management 32 (1), 25-38.

- Matthyssens, P., & Vandenbempt, K. (2008). Moving From Basic Offerings to Value-Added Solutions: Strategies, Barriers And Alignment. Industrial Marketing Management, 37(3), 316-328.

- Mentzer, J. T., Dewitt, W., Keebler, J. S., Min, S., Nix, N. W., Smith, C. D., & Zacharia, Z. G. (2001). Defining Supply Chain Management. Journal Of Business Logistics, 22(2), 1-25.

- Min,S., Mentzer,J.T., And Ladd,R.T., (2007). A Market Orientation in Supply Chain Management. Journal of Academic Marketing And Science, 35,507-522.

- Mohamed Udin, Z., Khan, M. K., & Zairi, M. (2006). A Collaborative Supply Chain Management Framework: Part 1-Planning Stage. Business Process Management Journal, 12(3), 361-376.

- Narver, J. C., & Slater, S. F. (1996), Competitive Strategy in Market-Focused Business. Journal of Market Focused Management, 1(2), 159-74

- Ou, C.S., Liu, F.C., Hung, Y.C., & Yen, D.C. (2010). A Structural of Supply Chain Management On Firm Performance. International Journal of Operation & Production Management. 30(5), 526-545.

- Salavou, H. (2005), Do Customer And Technology Orientations Influence Product Innovativeness In Smes? Some New Evidence From Greece, Journal Of Marketing Management, 21 (3/4), 307-338.

- Schendel, D. & C. Hofer (1979). Strategic Management: A New View of Business Policy and Planning. Boston: Little, Brown & Company.

- Shepherd, C., & Günter, H. (2011). Measuring Supply Chain Performance: Current Research and Future Directions. In Behavioral Operations In Planning And Scheduling (105-121). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Slater, S. F., & Narver, J. C. (1994). Does Competitive Environment Moderate The Market Orientation-Performance Relationship? Journal of Marketing, 58(January), 46–55.

- Stank, T. P., Paul Dittmann, J., & Autry, C. W. (2011). The New Supply Chain Agenda: A Synopsis And Directions For Future Research. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 41(10), 940-955.

- Thomas, D. J., & Griffin, P. M. (1996). Coordinated Supply Chain Management. European Journal of Operational Research, 94(1), 1-15.

- Trkman, P., Mccormack, K., De Oliveira, M. P. V., & Ladeira, M. B. (2010). The Impact of Business Analytics on Supply Chain Performance. Decision Support Systems, 49(3), 318-327.

- Urde, M., Baumgarth, C., & Merrilees, B. (2013). Brand Orientation and Market Orientation—From Alternatives To Synergy. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 13-20.

- Venkatraman, N. (1989). The Concept of Fit in Strategy Research: Toward Verbal and Statistical Correspondence. Academy Of Management Review, 14(3), 423-444.

- Vereecke, A.,& Muylle, S. (2006). Performance Improvement Through Supply Chain Collaboration In Europe. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 26(11), 1176–1198.

- Whitten, G.D., Green, K.W.J. And Zelbst, P.J. (2012). “Triple-A Supply Chain Performance”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 32 (1),28-48.

- Wisner, J. D. (2003). A Structural Equation Model of Supply Chain Management Strategies and Firm Performance', Journal Of Business Logistics, 24(1), 1-26.

- Wong, C. Y., Boon-Itt, S., & Wong, C. W. (2011). The Contingency Effects of Environmental Uncertainty On The Relationship Between Supply Chain Integration and Operational Performance. Journal of Operations Management, 29(6), 604-615

- Yu, K., Cadeaux, J., & Song, H. (2012). Alternative Forms of Fit In Distribution Flexibility Strategies. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 32(10), 1199-1227.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

22 August 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-013-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

14

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-883

Subjects

Sociology, work, labour, organizational theory, organizational behaviour, social impact, environmental issues

Cite this article as:

Yusoff, Y. B. M., Bin Ashari, H., & Bin Salleh, M. N. (2016). Strategic Fit and Supply Chain Performance (SCP): The Effect of Supply Chain Management (SCM) as The Mediator. In B. Mohamad (Ed.), Challenge of Ensuring Research Rigor in Soft Sciences, vol 14. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 584-592). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.08.83