Mapping the Market Success for Family Micro and Small Food Producers in Palestine: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

The mapping market plan and analysis for food processing cooperatives, micro and small organizations in the West Bank is an essential homework for Palestinian institutions in the Palestine to develop the family firms’ performance. The main objective of this paper is to help the private sector development enterprises in contributing to the expansion of small-scale food processing organizations. The paper expectations are to provide the micro and small businesses (MS) with the necessary analysis in building their capacity in terms of organizational, product development promotion and market access. The targeted population was local family cooperatives and organizations that engage in food processing in the West Bank. (MS) represents 14% of all the Palestinian firms, while the targeted sample was seven organizations were investigated empirically using the qualitative research method. The finding show that there are shortages in terms of strategies inventions and implementations, marketing systems fit with procedures, policies, and adaptations with internal weaknesses and external threats that effects the firms abilities to survive, sustain and improving the performance.

Keywords: Market planFamily CooperativesMicro and small businessproductionstrategy

Introduction

Economic growth potential in Palestine lies with the Palestinian private sector. The micro and small (MS)-scale, single owners and family enterprises dominate businesses. Large enterprises are still very limited in number. Micro and Small business enterprises make up a large proportion of the business sector in the Palestinian economy of the West Bank and Gaza Strip (WBGS). Data from the Palestinian Bureau of Statistics show that more than two-thirds of these enterprises employ less than five workers and families (PCBS.2013, 2014) run many.

This sector has a special importance for the Palestinian economy as a source of employment opportunities for families and individuals in WBGS. The fact that small business enterprises are so prevalent is due to the Israeli occupation, which since 1967 employed measures to restrict the development of the Palestinian economy and compel the occupied territories to be dependent on the Israeli economy. For example, after 28 years of observation Benvenisti et al., (1986) has noted that Israel's economic policy aimed at freezing the economic development of the Palestinian sector. Along with encouragement of living, based on income from work in Israel; economic prosperity for individual residents alongside economic stagnation at the communal level; discouraging independent economic development that would enter into competition with the Israeli economy, and prevention of independent economic development that could enable Palestinian political forces to establish power bases, and eventually a Palestinian state (Benvenisti, Abu-Zayed, & Rubinstein, 1986). This strategy hampered the expansion of Palestinian small enterprises into larger businesses.

Despite these facts, the large number of small enterprises and the special importance to the Palestinian economy. The private sector industrialists have been accustomed to profiting under difficult circumstances during the occupation, using their size as a source of flexibility in favorable market conditions. According the Ministry of economics in Palestine (2014), the Food Processing sector is one of the most rapidly developing sectors in the Palestinian economy. The vitality of the sector’s basic products as well as the recent developments in quality to meet international standards and requirements are both enhancing the sector in the local market and increasing the export capacities of local producers. Local market share increased from 20- 30% in market share for local producers. The majority of family business working in industry are working mainly in food industry, while the rest are working in various types of industries (Sabri, Jaber, AL-Bitawi, & Awwad, 2015). This increase is an indicator of the development and growth of the industry. Market studies reveal that the average family spends 42% of its income on food (PCBS. 2015), where the total market for Palestinian food products is approximately $35 million per year. It is indicating the importance of this sector and the need for a competitive local industry to provide high quality food products. Where the marketing processing of these firms face allot of challenges related to pricing, promotion, producing, and placing (Smirat& Nasser 2015). This paper examined empirically how these businesses can be developed through the marketing planning, and mapping. Reasoning mapping is a qualitative technique designed to identify cause and effect as well as to explain causal links (Montibeller, Belton, Ackermann, & Ensslin, 2008). It is used to structure, analyze and make sense of problems (Silverman, 2013).

This market mapping report is presented in two main sections; Section one presents the findings on four levels. Level one explains the overall assessment for the small and micro cooperatives and organizations working in the food-processing sector. In level, two introduces market analysis covering business models, consumer feedback, and retailers’ feedback. In the level three, we highlight new product development potential based on the research findings. In the last level highlights the individual mapping of each organization selected for this project. In section, two presents the recommended approach on two levels: firstly are the organizational level interventions in terms of support and primary activities for the selected organizations. Secondly marketing support in terms of Product, Price, Promotion and place (distribution).

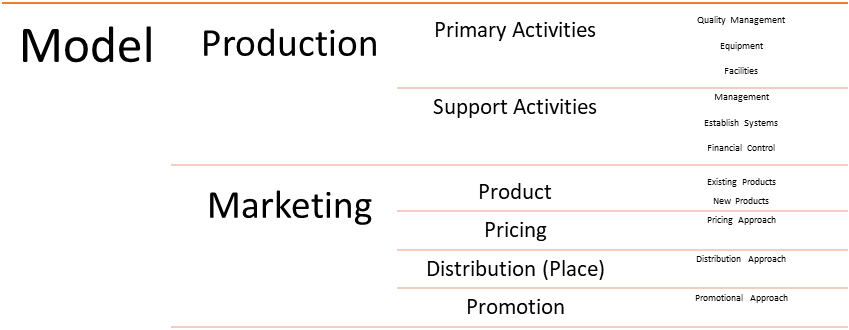

This mapping exercise and the recommended approach is based on two key concepts which are the Michael Porter value chain concept (Porter & Kramer, 2011), and the Jerome McCarthy four Ps of marketing (Perreault Jr, McCarthy, & Cannon, 2006). The recommended approach in this document focuses on the key success factors “KSF” that will produce the greatest return on investment for the targeted organizations.

Methodology

The research uses a qualitative mapping research approach (Maxwell, 2012) this approach has been used since it permits flexibility during data gathering, the choice and design of methods are constantly modified, based on ongoing analysis and findings. This allows investigation of important new issues and questions as they arise, and allows the investigators to drop unproductive areas of research from the original research plan.

The research used a purposive sampling method (Palys, 2008). Purposive sampling involves selection of organizations and individuals based on important characteristic under study, such as location, type of products produced, or marketing and sales (Guarte & Barrios, 2006). From our experience in ICP Bethlehem university of work with over 80 Palestinian cooperatives and organizations and therefore the selection process for the cooperatives was based on the extensive knowledge of producing cooperatives and organizations covering the west bank area with a focus on following districts (Hebron, Bethlehem, Ramallah, Nablus, Jenin, Toubas and Jericho). Unlike most quantitative studies, we interview organizations, cooperatives, retailers, distributors and other key stakeholders repeatedly in order to explore issues in-depth and identify the gaps and key success factors required for the success of empowering small producers in the food-processing sector.

In focus, the research identified subgroups or categories of people and organizations to be sampled. These include cooperatives and organizations that engage in food processing; consumers; and Retailers and wholesaler. The study has used different types of qualitative methods. Data gathering methods included key informant interviews (Sinkovics & Ghauri, 2008), direct observations (Gillenson & Sherrell, 2002), and narratives (Liu, 2006).

The variety of methods used ensures triangulations and increases the validity of the results. Interviewing precedes much like a dialogue between interviewee and interviewer. Questions are open-ended and the interviewer makes an active effort at building rapport with the interviewee. Usually, the interviewer explores relevant topics as the interviewee brings them up during the interview. In addition, the interviewer usually interviews the same informant several times to discuss certain issues in-depth (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009). Direct observation emphasizes observing and recording actual behavior. Observations may focus on customers, production sites, or production process. The observer records as much behavior as possible, including actions, conversations, and descriptions of the local and persons observed (Daymon & Holloway, 2010). A narrative records actual events around the process. The interview focuses on the sequence of events such as process of procurement, processing, packaging or marketing by the cooperative (N. Lee, Saunders, & Gummesson, 2005). The interviewer refers to a list of topics as a guide but remains flexible as to the order of discussion of topics listed.

Findings

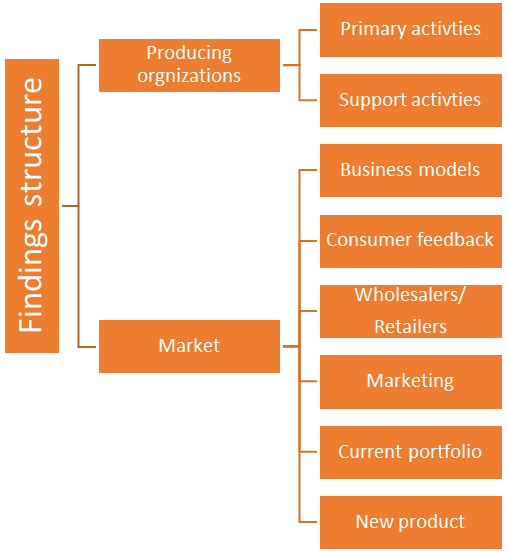

This findings section of the study covers the general finding and trends on two levels. First, it covers the producing organization from the procurement process to the products distribution and marketing. The second part of the findings section covers the wholesalers, retailers and consumers feedback. The following is the structure used to present the findings (Figure

Individual assessment and mapping results for selected organization

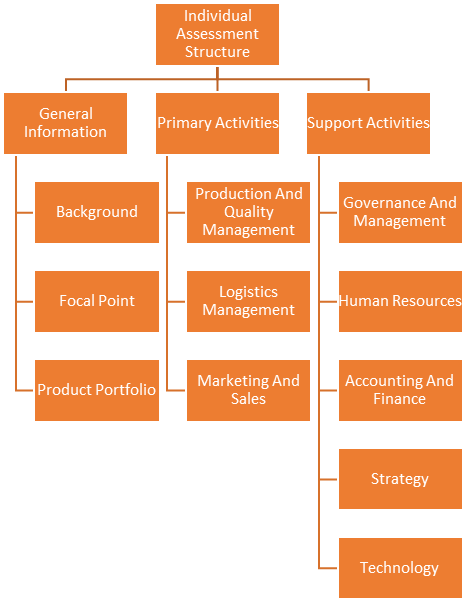

This individual assessment section of the study covers the capacity assessment finding for seven selected organizations that are considered a good fit for this project. The capacity assessment was conducted on mapping out the Porter Value Chain model as a tool to evaluate the key primary business functions and support business functions that are considered the key success factors and identify the gaps that need to be addressed according to this mapping exercise (Figure

The case of Turathuna Al Aseel

Turathuna Al Aseel was established in 2008 as women’s organization focusing on handcrafts production and food processing as means of economic empowerment for women. The general assembly of the cooperative is made up of 60 women members while the Board of directors is comprised of nine women members. The cooperative has the capacity and is currently engaged in Traditional Thyme Mix, Jams, Grape Molasis, Dried herbs, Traditional Palestinian hand stitched clothing and accessories, Olive oil soap (liquid and soap bars)

The Individual Capacity assessment takes into consideration the

Related to Human Resources; the organization does not have a clear recruitment system, or capacity building plans for its members and human resources. This is especially critical to the production workers that are responsible for product quality and hygiene. Whereas Accounting, Finance and Procurement; The cooperative does not have accounting software and all of the bookkeeping is conducted manually which makes financial analysis, financial reporting and costing a time consuming and challenging task. It was also observed that there is a need for a clear procurement policy with the appropriate forms and documentation to ensure that the cooperative attains its inputs at a competitive price in addition to ensuring transparency in its operation.

Related to Strategy; the organization’s management could not articulate the vision and mission of the organization although there is a strategic plan; this is attributed to the lack of management skills and understanding of the strategic plan importance by the management. It is also worth noting that the strategic plan should be conducted in a participatory manner with actionable, clear goals.

Technology; the organization use of technology in production is nonexistent and this is critically affecting the shelf life of products especially in two aspects; a) The dried products such as thyme and grains are not being vacuum sealed and there is no control for the product’s humidity before packaging which can result in product spoilage. b) As for the pickled products, jams and molasses the jars and bottles used are not being hygienically pasteurized to ensure protection against bacteria and mold. Moreover, the use of recycled cola bottles and reused jars is drastically affect the quality and appeal of the products. The cooperative can also benefit from a database for tracking customers and sales which will facilitate the process of contacting customers, tracking orders and generating reports.

Recommended Approach

The aim of this market mapping study is to identify the current market gaps, highlight the required key success factors for small producers in the food-processing sector and recommend an intervention that will contribute to increased production and sales by the targeted food processors.

After conducting a thorough market mapping analysis and meeting with producers, consumers, wholesalers, conducting individual organization assessment and interviewing key individuals, the key success factors were identified and can be grouped into two major points as follows;

References

- Bakar, H.A. & McCann, R.M. (2014).Matters of demographic similarity and dissimilarity in supervisor–subordinate relationships and workplace attitudes.International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 41, 1-16.

- Bulow, A.M. (2011). Culture and negotiation.International Negotiation, 16(3), 349-359.

- Cai, D.A., Wilson, S. & Drake, L. (2000). Culture in the context of intercultural negotiation, Human Communication Research, 26, 591–617.

- Carrell, M.R. &Heavrin, C. (2008).Negotiating essentials: Theory, skills and practices. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- De, C.K.W., Dreu, L.R., Weingart, L.R. & Kwon, S. (2000). Influence of social motives on integrative negotiation: A meta-analytic review and test of two theories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 889–905.

- Fisher, R. & Brown, S. (1991). Getting together: building relationships as we negotiate. New York: Penguin Books.

- Gahan, P.G. &Abeysekera, L. (2009). What shapes an individual's work values? An integrated model of the relationship between work values, national culture and self-construal. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(1), 126-147.

- Gelfand, M.J., Major, V.S., Rav, J.L., Nishii, L.H. & O'Brien, K. (2007).Negotiating relationally: The dynamics of the relational self in negotiations (CAHRS Working Paper #07-06). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cahrswp/463.

- Hames, D.S. (2012).Negotiation: Closing deals, settling disputes, and making team decision. United States: Sage Publications. Inc.

- Hendon, D.W., Hendon, R.A. &Herbig, P. (1998).Cross-cultural business negotiation. America: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.

- House, R., Javidan, H., Ruiz-Quintanilla, A., Dorfman, P.M. &Javidan, M. (1999).Culture influences on leadership and organizations: Project GLOBE.

- Hurn, B.J. (2007). The influence of culture on international business negotiations.Industrial and Commercial Training, 39(7), 354-360.

- Javidan, M. & House, R.J. (2001). Cultural acumen for the global manager: Lessons from project GLOBE. Organizational Dynamics, 29, 289-305.

- Javidan, M., House, R.J., Dorfman, P.W., Hanges, P.J. &Luque, D.M.S. (2006). Conceptualizing and measuring cultures and their consequences: a comparative review of GLOBE's and Hofstede's approaches. Journal of International Business Studies, 37.

- Jiang, Y. (2013). Business negotiation culture in China: A game theoretic approach. International Business Research, 6, 109-116.

- Ke, G. (2011). Cultural difference effects on business holding up Sino-US. Business negotiation as a model.Cross-cultural Communication, 7(2), 101-104.

- Kennedy, J.C. (2002). Leadership in Malaysia: Traditional values, international outlook. The Academy of Management Executive, 16(3), 15-26.

- Kumar, R. & Worm, V. (2003).Social capital and the dynamics of business negotiations between the northern Europeans and the Chinese. International Marketing Review, 20, 262-285.

- Kumar, R. &Patriott, G. (2011). Culture and International Alliance Negotiations: A Sensemaking Perspective. International Negotiation, 16, 511-533.

- Lee, K., Yang, G. & Graham, J.L. (2006). Tension and trust in international business negotiations: American executives negotiating with Chinese executives. Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 623-641.

- Lewicki, R.J., Barry, B. &Sauders, D.M. (2010).Negotiation (6th Ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

- Liu, M. & Wilson, S.R. (2011). The effects of interaction goals on negotiation tactics and outcomes: A dyad-level analysis across two cultures. Communication Research, 38, 248–277.

- Martin, J.N. & Nakayama, T.K. (2013).Intercultural communication in contexts (6th Ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

- Neuliep, J.W. (2012). Intercultural communication: A contextual approach. United States of America.

- Oetzel, J.G. (2001). Self-construals, communication processes, and group outcomes in homogeneous and heterogeneous groups. Small Group Research, 32(1): 19-54.

- Oetzel, J.G., Ting-Toomey, S., Masumoto, T., Yokochi, Y., Pan, X., Takai, J. & Wilcox, R. (2001). Face and facework in conflict: A cross-cultural comparison of China, Germany, Japan, and the United States. Communication Monographs, 68(3), 235-258.

- Okoro, E. (2001). Cross-Cultural etiquette and communication in global business: Toward a strategic framework for managing corporate expansion. International Journal of Business and Management, 7(16), 130-138.

- Phillipsen, S. &Littrell, R.F. (2011).Manufacturing quality and cultural values in China.Asia Pacific Journal of Business and Management, 2(2), 26 – 44.

- Sarkar, A.N. (2010). Navigating the rough seas of global business negotiation: reflection on cross-cultural issues and some corporate experiences.International Journal of Business Insights and Transformation, 3(2), 3-24.

- Schloesser, O., Frese, M., Heintze, A-M.et al. (2013). Humane Orientation as a New Cultural Dimension of the GLOBE Project: A Validation Study of the GLOBE Scale and Out-Group Humane Orientation in 25 Countries. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, 44, 535-551.

- Shi, X. & Wang, J. (2011).Cultural distance between China and US across GLOBE Model and Hofstede Model.International Business and Management, 2(1), 11-17.

- Tung, R.L. &Verbeke, A.V. (2010). Beyond Hofstede and GLOBE: Improving the quality of cross-cultural research. Journal of International Business Studies, 41, 1259–1274.

- Wilson, S. & Putnam, L. L. (1990).Interaction goals in negotiation.In J. Anderson (Ed.), Communication yearbook 13 (pp. 374–406). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Venaik, S. & Brewer, P. (2010).Avoiding uncertainty in Hofstede and GLOBE.Journal of International Business Studies, 41, 1294–1315.

- Zhao, J.J. (2000). The Chinese approach to international business negotiation. The Journal of Business Communication, 37(3), 209-237.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

22 August 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-013-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

14

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-883

Subjects

Sociology, work, labour, organizational theory, organizational behaviour, social impact, environmental issues

Cite this article as:

Smirat, I. M. H., & Shariff, M. N. M. (2016). Mapping the Market Success for Family Micro and Small Food Producers in Palestine: A Qualitative Study. In B. Mohamad (Ed.), Challenge of Ensuring Research Rigor in Soft Sciences, vol 14. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 212-219). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.08.31