Abstract

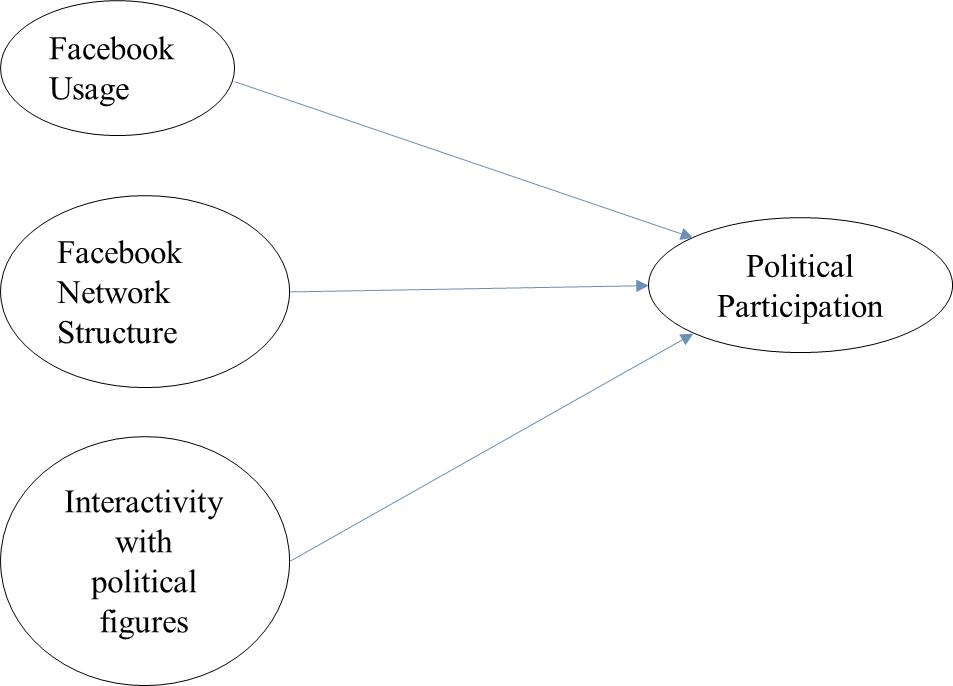

Youth political participation is indeed an engaging area of academic research that is increasingly evolving. However, some recent studies suggest that traditional form of political participation especially among youth has been declining in developed and developing countries which may likely create uncertain future for democracy. For instance, in many countries youth are not stimulated by the traditional media such as Radio, Television and Newspaper. Conversely, other findings illustrate the sudden and unprecedented increase in youth engagement in political activities through the use of Facebook. Youth now have access to political information and interact directly with political candidates. Nevertheless, researchers have not clearly examined why youth political participation suddenly changed and what it’s the driving force is. In posing these questions, scholars have suggested that certain features of Facebook such as usage pattern, diversity network of Facebook friends and interactivity with political figures should be examined. The paper therefore concludes that there exists a positive linkage between Facebook usage and youth political participation.

Keywords: Facebook usageyouth political participationNigeria

Introduction

Political participation includes political activities such as joining civic/political groups, interacting with politicians, voting, signing petition online, volunteering or participating in campaign (Tang & Lee, 2013) These types of political participation are the important components and foundations of successful democracy (McManimon, 2014). .However, researches have indicated that these types of political participation appear to be declining, particularly among the youth (Andolina, & Jenkins, 2002). Thus, scholars over the years have shown concern by investigating the reasons behind youth participation or not participating in political activities (Thun, 2014). These concerns are more apparent in countries characterized with youth declining to participate in political activities (Milner, 2008). Studies have revealed that youth are not interested in participating in political affairs and thus; do not engage in democratic process (Dahlgren, 2009). In addition, youth do not have trust in representative institutions as well as politicians (Blais & Loewen, 2009). In the light of this background, youth declining from political participation is now a serious concern to many democracies in both developed and developing countries (Skoric & Poor, 2013). For instance, young people are not stimulated by the traditional media such as radio, television and newspaper which invariably have limited influence on increasing their political interest (Dong, Toney, & Giblin, 2010). Before the coming of social media, space in newspaper and airtime on radio and television were limited and expensive; thus youth cannot express their opinion nor participate in politics through the old media

However, in recent years there has been a new development of political interest and participation among youth (Wyngarden, 2012) especially with the proliferation of social media such as Facebook; the pattern and options for political participation have tremendously changed. Facebook is now playing important role refer to as “migration process” wherein the youth are using the site to participate in political affairs (Waller, 2013). Furthermore, youth are now increasingly using Facebook to influence social and political change (Chan & Guo, 2013) and it is now facilitating new form of political participation among them (Dhaha & Igale, 2013) Thus, the question is why has youth political participation changed? What is it in Facebook that is influencing youth to participate in politics? In trying to answer these questions, some researchers have suggested examining certain features of Facebook such as usage pattern, the networks structure of friends on Facebook and interaction with political figures (Tang & Lee, 2013).

The coming of Facebook in the last few years has brought many changes in the political activities, for instance during American 2008/2012 Presidential Election, the Arab Spring in 2011, the Malaysian 2013 election(Gomez, 2014; Ternes, Mittelstadt, & Towers, 2014). The medium is open, participatory, interactive and cost effective than the outrageous political advertisement on the old media, thus it enables youth to engage with social and political issues using new participatory skills. But despite the fact that the advent of Facebook has now re-kindled youth political participation, little attention has been given to how Facebook usage and the nature of network of friends on Facebook influence the political participation among youth (Muntean, 2015). It is interesting to learn that literature has suggested interaction with Politian’s may likely influence political participation (Tang & Lee, 2013). Moreover, issues with regards to research methodology, such as context and sample population of some studies conducted on this issue were overwhelmingly conducted in Europe and United States using university or college students as samples (Zúñiga, Jung, & Valenzuela, 2012). Thus, this will not provide in-depth insight since political participation involves wider society. Therefore, a better sample that are diverse would be more appropriate to be a good representation (Conroy, Feezell, & Guerrero, 2012). So, by focusing on youth of voting age in the larger society that are more exposed and experienced in politics will be appropriate as it is important to expand research both in terms of the methodology used and samples population (Theocharis & Quintelier, 2014). According to UNESCO, youth is any person between the age of 18 and 35 years. This segment of population are the most active Facebook users around the world and research on this demographic and Facebook use is important as political behaviour formulated at a young age. This paper therefore seeks to provide a wider perspectives on why youth are using Facebook for political participation because concepts and practices need to be refined and better understood (Mohamad, 2013).

Literature

Political participation can be defined as the process of gathering and sharing of political information, interaction with politicians, participating in political campaign or taking part in voting exercise, (Dalton, 2008; Evans, 2003). Some literatures have categorised political participation into two types, conventional and unconventional political participation. Conventional participation refers to a behaviour of being a responsible citizen by attending and participating in a regular election exercise (Dimitrova, Shehata, Stromback, & Nord, 2011), while unconventional participation simply means any legal activity that sometime shows a sign of inappropriate manner such as signing petition, organising and supporting boycotts and staging demonstration or protests in public places. Additionally, political participation can be categorized into two offline and online political participation.

Traditional Political Participation

Traditional participation such as voting especially during election has been considered as important to a healthy democracy (Skoric & Kwan, 2011) and become an area of research to many scholars. This can be further supported by the definition of political participation as the activity that allows citizens to express their wishes and aspirations and also to some extents influence the selection of government or public officials that will create good policy (Norris, 2001). This development has created long discussions among scholars that even though youth engagement and electoral turnout appears to be low in different countries but some studies suggest that other forms of youth political participation such as online activities may likely indicate upward direction and tendency of their participation. Additionally, activities such as demonstrations and protests have now become apparent in youth (Dalton, 2011).Conversely, some scholars argue that declining political participation among youth is not an issue of much concern because they have shifted their interest from traditional political participation to what is now referred to as alternative type of participation such as joining online Facebook activities (Thun, 2014) .Thus, it may be accurate to say that youth have now prefer to participate in an interactive, accessible online medium which make more information available to many youth from different sources.

Online Political Participation

Online participation are the political activities such as sending messages to the politicians’ Facebook page, seeking donation for a political party or sharing political information on Facebook (Jung et al., 2011) and this has provides youth more ways to be active in political affairs that was not possible in the past generations. Apparently, studies have demonstrated that youth are disengaging from traditional political activities because their interest in politics is not acknowledged and represented. Nevertheless, this paper strongly advocates that Facebook usage may likely increase both online and offline political participation among youth, considering the fact that youth participation in political affairs is central to democracy and its absence may affect the upcoming generation. Thus, understanding what motivates youth to participate in political activities is now a major area of interest for researchers and students of social media and political communication (Jung et al., 2011) which was ignited by the assumption from scholars that youth political participation have been decreased for more than two decades now (Kann, Berry, Gant, & Zager, 2007). The role of Facebook towards influencing youth non-participatory behaviour has now become a serious growing interest especially with the increasing popularity of online political activities on Facebook among youth (Bakker & Vreese, 2011).

Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses

Facebook Usage

Facebook is the most popular social media site in the world with over 1 billion registered accounts (Amazing Facebook statistics, 2015). Facebook was first founded by Mark Zuckerberg in 2004 as a platform for college students in America and later in 2006 the service was opened to any interested user with an e-mail address. Facebook usage in this paper means the frequency and intensity of youth using the site which includes time spent hourly or daily (Lampe, Ellison, & Steinfield, 2007). Evidently, the use of Facebook recently for political participation, worldwide has greatly increased especially among youth (Skoric & Poor, 2013) and they are particularly using the site to influence social and political change. Studies have suggested that youth are now using Facebook to seek for political information, mobilize like minds, create user-generated content and share political views (Thun, 2014). Aside from this, there is little research addressing the pattern of Facebook use among youth (Chan & Guo, 2013).

Studies have indicated that Facebook is more powerful than traditional media because it provides a similar and advanced feature in terms of exposure to information but has the additional benefits and advantages of global reach, better quality and greater speed and also an interactive medium of political discussion. With these features, Facebook plays a significant role in the formation of political knowledge. Youth today get their political information from Facebook rather than the legacy traditional media such as radio, television and newspapers. The information given is more interactive, user friendly, concise and easier to comprehend. In light of the above evidence, it becomes clear that Facebook usage may likely increase political participation among youth (Vissers, Hooghe, Stolle, & Maheo, 2012) and lead to traditional participation. Additionally, studies have found a positive relationship between the intensity of Facebook usage and civic and political participation (Zúñiga et al., 2012) Two deferent researches have clearly examined the link between Facebook usage and political participation and suggested that Facebook usage is relevant to both online and offline participation (Conroy et al., 2012; Vitak et al., 2011).

Facebook foster exposure to political mobilization and make political information more available, the medium is a potential means of recruiting people that were not politically motivated before into a new political activity. Thus, the accessibility and interactivity nature Facebook can effectively function as what is now referred as ‘gateway participation’ (Vissers et al., 2012). Thus, we propose the first hypothesis on the Facebook usage and political participation among youth.

Hypothesis 1. Level of Facebook usage positively influences the level of political participation among youth.

Facebook Network Structure

Facebook network structure in this paper refers to the diverse and network of friend online that cut across different geopolitical and ethnic backgrounds. Study have indicated that online social network size considerably may likely increase political participation (Muntean, 2015) and this may means that if a person connect and relate with many people that are from different culture and environment politically, the amount of political information that person may get is likely to be higher and influence him to participate Thus, Facebook as one of the social network site has evolve from being a network of document to now a network of people, it has exhibit a high level of online penetration with over 1.49 billion monthly users (Zephoria Internet Marketing Solution, 2015) Nevertheless, a study found that online network structure that is number of friends significantly hypothesises political participation Obviously, the size and number of friends in youth’s network determines the volume of information they may get and also the people located in that type of networks may likely be exposed and introduced to a substantive variety of information. Similarly, Young and Haase (2009) argued that personal online network size is positively related to the large amount of information an individual receive. Thus, we hereby propose a second hypothesis on Facebook network structure and political participation among youth.

Hypothesis 2: The structure of Facebook network positively influences the level of political participation among youth.

The Concept of Interactivity with Political Figure

Interactivity is one of the important features of online participation which encourage users to interact with both content and sender of the message. In this paper, interactivity with political figures is the process of two way flow of information and becoming a ‘friend’ through Facebook account or rather ‘Wall’ with a public elected politicians, (Zheng, 2015). Facebook provides a great opportunity to political figures to reach out to their constituents and voters. The technology also link and facilitates interaction between community and elected political representatives by providing a public online ‘Wall’ a space where community members can easily write comments in favour or against their political leaders (Lahabou & Wok, 2011).

Recent literature shows that social interaction contributes positively to event participation, for instance people especially youth are more willing to honour invitation sent by someone they have already established relationship and interacted with (Leung & Lee, 2014). Thus, information that is distributed through multiplex networks and with existing established relationship and interaction via Facebook for example in which people are already connected online may likely trigger participation (Huang, Wang, & Yuan, 2014). While social media in general and Facebook in particular provides important opportunities for youth to interact with politicians and various stockholders, youth can become friends and initiate other linkages with political figures through Facebook. Consequently, youth ‘friendship’ and interaction with those important political figures are likely to be vital source of political information and viewpoint. Thus, interactions with these political figures may increase political participation because political interactivity and discussions may likely stimulate interest to participate in political activities due to the fact that the process of interaction itself influences opinion formation (Valenzuela, Arriagada, & Scherman, 2014). Based on the above evidences, we wish to propose the third hypothesis on interactivity with political figures and political participation among youth.

Hypothesis 3. Level of interaction with political figures positively influences political participation among youth.

Conclusion

From the foregoing, it is imperative to state that political participation amongst youth is largely dependent on the use of Facebook and more youth are showing stronger reliance on the Facebook as their platform for securing political information they need to make their informed political decisions.

References

- Bakker, T. P., & Vreese, C. H. (2011). Good News for the Future? Young People, Internet Use, and Political Participation. Communication Research, 38(4), 451–470.

- Bang, H. P. (2005). Among everyday makers and expert citizens. In Remaking governance: Peoples, Politics and the Public sphere (pp. 159–178).

- Blais, A., & Loewen, P. (2009). Youth Electoral Engagement in Canada. Vasa, (January), 1–26. Retrieved from http://medcontent.metapress.com/index/A65RM03P4874243N

- Chan, M., & Guo, J. (2013). The Role of Political Efficacy on the Relationship Between Facebook Use and Participatory Behaviors: A Comparative Study of Young American and Chinese Adults. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(6), 460–463.

- Conroy, M., Feezell, J. T., & Guerrero, M. (2012). Facebook and political engagement: A study of online political group membership and offline political engagement. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(5), 1535–1546.

- Curran, J., Fenton, N., & Freedman, D. (2012). Misunderstanding the internet. Routledge.

- Dahlgren, P. (2009). Media and political engagement, (1995). Retrieved from http://www.langtoninfo.co.uk/web_content/9780521527897_frontmatter.pdf

- Dalton, R. J. (2008). Citizenship Norms and the Expansion of Political Participation. Political Studies, 56(1), 76–98.

- Dalton, R. J. (2011). Introduction: The Debates over Youth Participation. Engaging Youth in Politics: Debating Democracy’s Future, New York and Amsterdam: International Debate Education Association, 1–15.

- Damon, W. (2001). To not fade away: Restoring civil identity among the young. Making Good Citizens: Education and Civil Society, 122–141.

- Dhaha, I. S. Y., & Igale, A. B. (2013). Facebook Usage among Somali Youth: A Test of Uses and Gratificaitons Approach. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 3(3), 299–313.

- Dimitrova, D. V., Shehata, a., Stromback, J., & Nord, L. W. (2011). The Effects of Digital Media on Political Knowledge and Participation in Election Campaigns: Evidence From Panel Data. Communication Research, 41(1), 95–118.

- Dong, Q., Toney, J., & Giblin, P. (2010). Social network dependency and intended political participation. Human Communication, 13, 13–27.

- EACEA. (2013). Youth in Action: Beneficiaries space 2013. Retrieved from http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/youth/beneficiaries/2013/index_en.php

- Evans, J. H. (2003). Have Americans’ attitudes become more polarized? - An update. Social Science Quarterly, 84(1), 71–90.

- Farson, H. (2013). What matters ? Exploring Youth Political Participation in Western Democracies. Simon Fraser University.

- Feezell, J. T., Conroy, M., & Guerrero, M. (2009). Facebook is... fostering political engagement: A study of online social networking groups and offline participation. Fostering Political Engagement: A Study of Online Social Networking Groups and Offline Participation.

- Gomez, J. (2014). Malaysia’s 13th General Election: Social Media and its Political Impact. Asia Pacific Media Educator, 24(1), 95–105.

- Harris, A., Wyn, J., & Younes, S. (2010). Beyond apathetic or activist youth. Young, 18(1), 9 –32.

- Henn, M., Weinstein, M., & Wring, D. (2002). A generation apart? Youth and political participation in Britain. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 4(2), 167–192.

- Himelboim, I., Mccreery, S., & Smith, M. (2013). Birds of a Feather Tweet Together: Integrating Network and Content Analyses to Examine Cross-Ideology Exposure on Twitter. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18, 40–60.

- Howard, P. N., & Hussain, M. M. (2011). The Role of Digital Media. Journal of Democracy, 22(3), 35–48.

- Huang, A.-J., Wang, H.-C., & Yuan, C. W. (2014). De-virtualizing social events: understanding the gap between online and offline participation for event invitations. Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing - CSCW ’14, 436–448

- Jung, N., Kim, Y., & de Zúñiga, H. G. (2011). The Mediating Role of Knowledge and Efficacy in the Effects of Communication on Political Participation. Mass Communication and Society, 14(4), 407–430.

- Kann, M. E., Berry, J., Gant, C., & Zager, P. (2007). The internet and youth political participation. First Monday, 12, 1.

- Keeter, S., Zukin, C., Andolina, M., & Jenkins, K. (2002). Improving the Measurement of Political Participation. Paper Presented at The Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association.

- Lahabou and Wok. (2011). Relationship between Facebook Usage and Youth Political Participation: A Sub-Saharan African Context. Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, 1–10.

- Lampe, C., Ellison, N., & Steinfield, C. (2007). A Familiar Face ( book ): Profile Elements as Signals in an Online Social Network. Technology, 435–444.

- Leung, D. K. K., & Lee, F. L. F. (2014). Cultivating an Active Online Counterpublic: Examining Usage and Political Impact of Internet Alternative Media. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 19(3), 340–359.

- Lusoli, W., Ward, S., & Gibson, R. (2006). (Re)connecting politics? Parliament, the public and the Internet. Parliamentary Affairs, 59(1), 24–42

- Marlowe, A. D. (2009). Online Social Networking Effect on political Participation,and The Digital divide, (December).

- McManimon, S. J. (2014). Political Engagement and the Shifting Paradigm from Traditional to Social Media. Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

- Micheletti, M., & Stolle, D. (2011). The market as an arena for transnational politics. Engaging Youth in Politics: Debating Democracy’s Future. IDEBATE Press.

- Miller, P. R., Bobkowski, P. S., Maliniak, D., & Rapoport, R. B. (2015). Talking Politics on Facebook: Network Centrality and Political Discussion Practices in Social Media. Political Research Quarterly, 68(2), 377–391.

- Milner, H. (2008). The Informed Political Participation of Young Canadians and Americans.

- Mohamad, B. (2013). The Structural Relationships between Corporate Culture, ICT Diffusion Innovation, Corporate Leadership, Corporate Communication Management (CCM) Activities and Organisational Performance, (CCM). Unpublished PhD Thesis. Brunel University London

- Muntean, A. (2015). The Impact of Social Media Use of Political Participation. Aarhus University.

- Norris, P. (2001). Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty, and the Internet Worldwide. Communication Society and Politics.

- Phelps, E. (2004). Young citizens and changing electoral turnout, 1964–2001. The Political Quarterly, 75(3), 238–248.

- Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling Alone:The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Politologija.

- Scheufele, D. a., Nisbet, M. C., & Brossard, D. (2003). Pathways to Political Participation? Religion, Communication Contexts, and Mass Media. Int J Public Opin Res, 15(3), 300–324.

- Skoric, M. M., & Kwan, G. (2011). Do Facebook and video games promote political participation among youth? Evidence from Singapore. eJournal of eDemocracy and Open Government, 3(1), 70–79.

- Skoric, M. M., & Poor, N. (2013). Youth Engagement in Singapore: The Interplay of Social and Traditional Media. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 57(2), 187–204.

- Smith, Schlozman, Verba, & Brady. (2009). The Internet and Civic Engagement. Pew Internet. Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/15--The-Internet-and-Civic-Engagement/1--Summary-of-Findings.aspx

- Tang, G., & Lee, F. L. F. (2013). Facebook Use and Political Participation: The Impact of Exposure to Shared Political Information, Connections With Public Political Actors, and Network Structural Heterogeneity. Social Science Computer Review, 31(6), 763–773.

- Ternes, A., Mittelstadt, A., & Towers, I. (2014). Arabian Journal of Business and Using Facebook for Political Action ? Social Networking Sites and Political Participation of Young Adults, 3(9).

- Theocharis, Y., & Quintelier, E. (2014). Stimulating citizenship or expanding entertainment? The effect of Facebook on adolescent participation. New Media & Society, 1461444814549006–.

- Thun, V. (2014). Youth political participation in Cambodia: Role of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs). Northern Illinois University.

- Valenzuela, S., Arriagada, A., & Scherman, A. (2014). Facebook, Twitter, and Youth Engagement: A Quasi-experimental Study of Social Media Use and Protest Behavior Using Propensity Score Matching. International Journal of Communication, 8, 25. Retrieved from

- Vissers, S., Hooghe, M., Stolle, D., & Maheo, V. -a. (2012). The Impact of Mobilization Media on Off-Line and Online Participation: Are Mobilization Effects Medium-Specific? Social Science Computer Review, 30(2), 152–169.

- Vitak, J., Zube, P., Smock, A., Carr, C. T., Ellison, N., & Lampe, C. (2011). It’s complicated: Facebook users' political participation in the 2008 election. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 14(3), 107–114.

- Waller, L. G. (2013). Enhancing Political Participation in Jamaica: The Use of Facebook to “Cure” the Problem of Political Talk Among the Jamaican Youth. SAGE Open, 3(2).

- Wyngarden, V. (2012).New participation, new perspectives ? Young adults political engagement using Facebook Submitted by Katharine E . Colorado State University.

- Xenos, M., & Lance Bennett, W. (2007). The Disconnection In Online Politics: the youth political web sphere and US election sites, 2002–2004. Information, Communication & Society, 10(4), 443–464.

- Zheng, Y. (2015). Explaining Citizens’ E-Participation Usage: Functionality of E-Participation Applications. Administration & Society, in press, 1–20.

- Zúñiga, H. G. de, Jung, N., & Valenzuela, S. (2012). Social Media Use for News and Individuals’ Social Capital, Civic Engagement and Political Participation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 17(3), 319–336.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

22 August 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-013-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

14

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-883

Subjects

Sociology, work, labour, organizational theory, organizational behaviour, social impact, environmental issues

Cite this article as:

Abdu, S. D., Mohamad, B., & Muda, S. (2016). New Perspectives to Political Participation among Youth: The Impact of Facebook Usage. In B. Mohamad (Ed.), Challenge of Ensuring Research Rigor in Soft Sciences, vol 14. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 127-134). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.08.19