Abstract

Colleting the data through a survey in the Northern region of Malaysia; Kedah, Perlis, Penang and Perak, this study investigates intergenerational social mobility in Malaysia. We measure and analysed the factors that influence social-economic mobility in Malaysia. In estimating the factors that influence social-economic mobility, we employ a binary choice model based on the maximum likelihood method. The social mobility variable is measured using the difference between the educational achievement between a father and his son. If there is a change of at least of two educational levels between a father and his son, then this study will assign the value one (1) which means that social mobility has occurred. We found that besides father’s education, father’s attitude and the establishment of a university in the area have also contributed to social mobility of the rural communities.

Keywords: povertysocial mobilityMalaysia

Introduction

In Malaysia, it is crucial to measure the ‘equality’ of society more along the lines of economic social mobility rather than purely through the income or wealth measures. The idea is to have people begin at more or less the same starting point, then proceed in accordance to their own ability and willingness to work. Economic mobility in this sense means that whatever your personal circumstances, you can reach the top of the social and economic ladder. This kind of viewpoint tolerates high income and wealth inequality as the product of a system where everyone has a fair chance.

Intergenerational mobility reflects a host of factors, including inherited traits, investment on human capital (education), public policies and social norms that may influence the individual ability and to seize economic opportunities. If you start off disadvantaged, the odds are stacked against you. For the vast majority of the population, educational attainment and lifetime earnings are as much a product of your background as they are your innate abilities. In other words, where you start from actually matters and intergenerational transfer of wealth skews things considerably. Worse, even a completely equal and meritocratic society will degenerate into a fully unequal society unless there is social or public intervention.

The status of intergenerational social mobility can be measured in several ways, by income, education, occupation or social class. More often, economic research has focused on wages or income. Ideally, income should be measured by a household’s disposable income because it is most directly influences the standard of living (e.g Chadwick and Solon, 2002; Solon, 2004). In practice, accurate measurement of a household’s disposable income is difficult because of the structure of the household. Therefore, most existing studies use some measure of wages.

There are a variety of public and private development projects in the rural areas. Educational institutions such as primary schools, secondary schools, colleges, and universities sprouted conspicuously as well as infrastructure facilities such as roads, airports enlarged and upgraded as an international airport and so on. These things are the new engine of growth in the rural communities.

However, what is the position of the rural communities today compared to ten or fifteen years ago? Have their families escaped the cycle of poverty and backwardness?

As we all know, education is an important factor to bring change. Education is one of the highest dimensions of the Malays to experience mobility since colonial times until today. Educational achievement can determine whether a person will follow in their father’s footstep as farmers and labourers or secures high positions in public administration or private sector. Success factor in education is associated with the ability to mobilise from lower socio- economic strata to higher strata.

Nevertheless, according to some researchers, the culture of putting an emphasis on education among the rural communities is still low. One very important thing to consider is the awareness of parents to inspire and motivate their children to work hard is still low when compared with other community members who live in the cities.

Hence, this study decides to examine about what are the factors that contribute or otherwise hinder social mobility from occurring in the rural communities? Are the internal factors at the father’s and the family’s stage still not strong enough to encourage their children to change?

Literature Review

Educational opportunities for the whole family can transmit the motivation to succeed to children. Lillard & Kilburn (1995) showed that education regimes where access to education is unfavourable to lower income families adversely affect intergenerational mobility. Solon (1999) theoretical model reveals that a more progressive public investment in human capital tends to increase mobility. Another theoretical model by Davies, Zhang and Zeng (2004) affirms that “starting from the same inequality, mobility is higher under public than under private education”. However, an empirical study of Britain by Blanden, Gregg and Machin (2005) found that “the big expansion in university participation has tended to benefit children from affluent families more and thus reinforce immobility across generations”.

Louw, Berg and Yu (2006) investigated the role that parents’ education plays in children’s human capital accumulation. The study analyses patterns of educational attainment in South Africa during the period 1970-2001, asking whether intergenerational social mobility has improved. It tackles the issue in two ways, combining extensive descriptive analysis of progress in educational attainment with a more formal evaluation of intergenerational social mobility using indices constructed by Dahan and Gaviria (2001) and Behrman, Birdsall and Szekely (1998). Both types of analysis indicate that intergenerational social mobility within race groups improved over the period, with the indices suggesting that South African children are currently better able to take advantage of educational opportunities than the bulk of their peers in comparable countries. However, significant racial barriers remain in the quest to equalise educational opportunities across the board for South African children.

Causa, Dantan and Johansson (2009) examines the potential role of public policies and labour and product market institutions in explaining observed differences in intergenerational wage mobility across 14 European OECD countries. Their empirical results show that education is one important driver of intergenerational wage persistence across European countries. There is a positive cross-country correlation between intergenerational wage mobility and redistributive policies, as well as a positive correlation between wage-setting institutions that compress the wage distribution and mobility.

3. Methodology

This study involves four states in the north Peninsular Malaysia which are Perlis, Kedah, Penang and Perak. All respondents are located in the rural areas. The sampling frame was obtained from the Statistics Department, Kuala Lumpur. Though the originally given sample was 400, after undergoing data refining process, the total number suitable for analysis was only 333. All these respondents met the study criteria which is a father who is 50 years old and above and have at the very least one son who is working.

In estimating the factors that influence social-economic mobility, we employ a binary choice model. Number 0 and 1 is used as a Dummy dependence variable. The value (1) is given if there is social mobility occurring between a father and his son. The social mobility variable is measured using the difference between the educational achievement between a father and his son. If there is a change of at least of two educational levels between a father and his son, then this study will assign the value one (1) which means that social mobility has occurred. For instance, if the father has a primary school education and the son has at least a higher secondary education (SPM), then it is declared that social mobility has occurred.

Meanwhile, the value zero (0) shows there has been no change in the educational level between a respondent and his son. For example, if a father is a SPM holder and his son is also a SPM holder, then it is said that social mobility does not exist. Nevertheless, if the father has a tertiary level education and the son also has the same level of education, then this study will assign the value one (1), meaning social mobility exists.

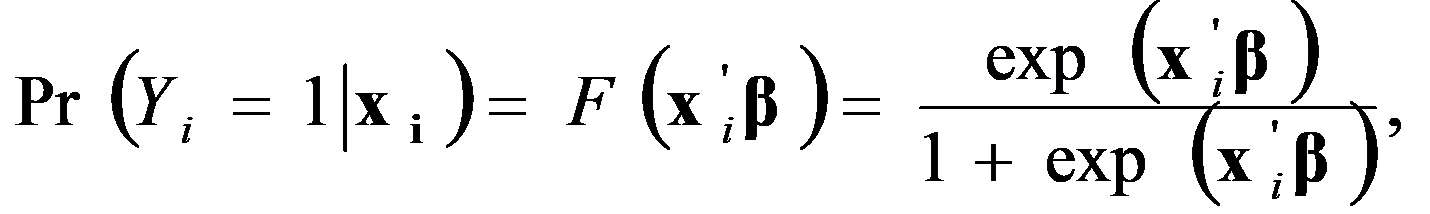

The logit model used in this study:

where:

Yi = 1 (mobility) if Yi* > 0

Yi = 0 (no-mobility) if Yi* ≤ 0

Xi = vector of independent variables

The error term,

where

xi’= [Edu_Fatheri Att_Fatheri Inv_Communityi Asseti Avaiable_Unii Near_Towni Near_highwayi Near Bus Stationi Near_Tourism Loci]

Equation (2) is used to estimate the probability of occurrence of social mobility. Whether the independent variable has a positive or negative impact on the dependent variable is refer to the sign of the estimated parameter (Wooldridge, 2002). In addition, the odds ratio is to examined the impact of the independent variables on the dependent variable. With the independent variables value, the estimated value for the dependent variable could be interpreted as the probability of the respondent gaining mobility (Greene 2000; Long dan Freese 2006; Maddala 1983).

Finding

The following discussion presents the details of the factors that have influenced the position and the changing patterns of social mobility of the rural population. The analysis was based on five factors: the father’s level of education, the father’s attitude, the father's involvement in the community, ownership of assets, and the provision of space and opportunity by the government.

In this analysis, the social mobility variable is measured by using the difference of the level of educational attainment between the respondent and his son. In using the logit model analysis, a dichotomous dependent variable or a variable that has only two decision values has been set, whether one (1), that is the existence of social mobility and zero (0) there is no social mobility. As described in the methodology section of the study, in the event of at least the are two changes in the level of education between the respondents and his son, then this study will give the value one (1) and vice versa.

The logit regression analysis uses nine independent variables which are Education level of father (Edu_Father); Attitude of the father (Att_Father ); Father’s involvement in the community (Inv_Community); Ownership of assets in the family (Asset); Existence of a university in the immediate vicinity of the repondent’s house (Available_Uni); Distance of respondent’s house to the town centre (Near_Town); Distance of respondent’s house to the highway (Near_highway); Distance of respondent’s house to the bus stop (Near Bus Station) and Position of the respondent’s house with tourism centre ( Near_Tourism_Loc).

This study uses the value of the odds ratio to illustrate the likelihood of a change in social mobility. The odds ratio value is a figure that reflects the value of the choice of whether there is a change in the level of social mobility or not.

The factor of father's education level (Edu_Father) shows significant value at the 1 percent significance level in determining the existence of social mobility. The positive correlation means that the higher the father’s education level, there is a higher probability for the occurrence of social mobility. This situation is the same as what was anticipated at the beginning of the study. This situation may arise because when a father who is also a leader in the family has high education, then he (the father) would feel more responsible for ensuring that his children also acquire an education level that is equally high or higher than himself. The estimation results also show that the effect of a change in the father’s level of education (Edu_Father) as indicated by the odds ratio in the father's education level is 1.9530. This means that one educational level increase in the father’s education will cause the odds value of the occurrence of social mobility to increase by a factor of 1.95, ceteris paribus.

The factor of father’s self-identity or attitude (Att_father) is also significant at the 5 percent level of significance in determining the occurrence of social mobility. There are four elements of identity measured using a Likert scale considered in the analysis which are the motivation to work hard, willingness to learn new things, willingness to take risks and not easily demotivated.

The study found that there is a positive relationship between these factors with social mobility and it is in line with the expectations at the beginning of the study. This means that the higher the value or amount of a father’s self-identity, the higher the probability of the occurrence of a change in the level of the son’s education and vice versa.

This situation may arise because when a father who is also a leader in the family has a positive self-esteem, then this father’s attitude will lead to the formation of positive behaviour of his children as well. The study found that the effect of changes in the father’s self-esteem father (Att_father) shown by the odds ratio of self-identity is 8.3846. This means that a one per cent increase in a father’s self-esteem will cause the odds of the occurrence of social mobility to be increased by a factor of 8.38, ceteris paribus.

The establishment of a college or university that is close to the respondent’s residence is found to have a statistically significant relationship at the 1 percent level of significance, to the probability of the existence of social mobility. The establishment of an institution of higher learning indirectly affect parents' awareness of the importance of education. Activities or education and community service programmes carried out by universities and their students in the local community provide exposure to parents and their children about higher education. For example, universities often carry out motivational programmes to SPM and STPM students to foster their interest to continue learning and succeeding in their studies.

5. Conclusion

The study was based on a theoretical stance that no one single factor can explain social mobility. In contrast, changes in the mobility form should be seen within the framework of a multi-causal or multi–factoral analysis. For social mobility to occur, the person needs a combination of the driving factors, in particular, the factors of education, occupation, attitude, asset ownership and the role of government simultaneously. In examining the factors that influence socio-economic mobility, we used logit model with nine independent variables. The odds ratio value is used to analyse the probability of changes that occurs in the factor that leads to social mobility. Out of the nine variables, only three are significant (father's education, father's attitude, the existence of a university in the near vicinity).

Those that are in the high mobility position are fathers who have strong spirits and internal ability compared with fathers who experienced decreased mobility. Strong internal ability is seen through high self-regard to change. The importance of development projects implemented by the government is perceived as one of the main factors that influence social mobility where 99.28% of the respondents agree that the existence of higher learning institutes helps to stimulate social mobility.

References

- Behrman, J., Alejandro Gaviria and Miguel Székely, (2001). Intergenerational Mobility in Latin America, Inter-American Development Bank, Research Department, WP #452,

- Behrman, Birdsall and Székely, (1998). Intergenerational Schooling Mobility and Macro Conditions and Schooling Policies in Latin America, IDB Publications (Working Papers) 6446, Inter-American Development Bank.

- Blanden, J.. Essays on intergenerational mobility and its variation over time, place and family structure, PhD Thesis, University of London (2005)

- Causa, O., Dantan, S., and Johansson, A. (2009). Intergenerational social mobility in European OECD countries. OECD Economics Department Working Paper No. 709. OECD

- Chadwick, L., and Solon, G. (2002).Intergenerational income mobility among daughters. The American Economic Review, 92(1), 335-344.

- Dahan, M. and Gaviria, A. (1999). Sibling correlations and social mobility in Latin America. Inter- American Development Bank, Office of the Chief Economist, WP# 395,

- Davies, J. B., Zhang, J. & Zeng, J. (2004). Intergenerational mobility under private vs public Education”. Manuscript.

- Greene, W. H. (2000). Econometric Analysis. New Jersey:Prentice-Hall International, Inc.

- Lillard, L. A. and Kilburn, R. M. (1995). Intergenerational earnings links: sons and daughters. RAND Working Paper Series 95-17

- Louw, M., Van der Berg, S. and Yu, Derek.. (2006). Educational attainment and intergenerational social mobility in SA, Conference Paper of the Economic Society of South Africa, Department of Economics, University of Stellenbosch, Durban.

- Long, J. Scott & Jeremy Freese. (2006). Regression model for categorical dependent variables using stata. Texas: Stata Press Publication Stata, Corp LP College Station.

- Maddala, G.S. (1983). Limited-Dependent and Qualitative variables in Econometrics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Solon, G. (1999). Intergenerational Mobility in the Labor Market. In Handbook of

- Labor Economics, Vol 3A. Ashenfelter, O. C., and Card, D. (eds). Amsterdam: North-

- Holland, pp. 1761-800.

- Solon, G. (2004). A model of intergenerational mobility variation over time and place. In Generational income mobility in North America and Europe, M. Corak (eds.), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England.

- Wooldridge, J.M. (2002). Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

22 August 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-013-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

14

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-883

Subjects

Sociology, work, labour, organizational theory, organizational behaviour, social impact, environmental issues

Cite this article as:

Mat, S. H. C., Zainal, Z., & Harun, M. (2016). Factors that Influence Social-Economic Mobility in the Northern Region of Malaysia. In B. Mohamad (Ed.), Challenge of Ensuring Research Rigor in Soft Sciences, vol 14. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 877-883). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.08.123