Abstract

Safety at work is one of the key issues in many organizations. This is because accidents and injuries in the workplace can cost the organization financially and non-financially. Although workplace safety has been widely investigated, less attention is given to the small and medium enterprises. Such neglect is unfortunate because many accidents and injuries around the world, including Malaysia, happen in this organizational milieu. This paper argues that despite having limited resources to install an integrated system of occupational safety and health (OSH), concern about workplace safety should not be ignored. Against this backdrop, this paper proposes a model that hypothesizes the role of safety management practices in promoting safety compliance.

Keywords: Safety Management PracticesSafety ComplianceSmall Medium Enterprises (SME)Malaysia

1. Introduction

There is no doubt that small and medium enterprises (SMEs) play a critical role in the economic development and progress of any nation (Kongolo, 2010). Like in other countries, SMEs contribute to the economy in various ways, such as by providing employment to the people (Salleh & Ndubisi, 2006). In Malaysia, the growth of SMEs is projected to increase by 5.5 percent and 6.5 percent in 2014 in comparison to 6.3 percent in 2013 (SME Annual Report, 2014). However, despite this positive outlook, this sector is plagued by many occupational accidents and injuries (Aziz, Baruji, Abdullah, Him, & Yusof, 2015; Surienty, Hong, & Hung, 2011). Aziz et al. (2015) reported that during 2010 and 2012, between 80 and 90 percent of occupational accidents were reported in SMEs in Malaysia. In this regard, Malaysia is not unique because SMEs in other countries, such as Europe, are 4.9 times likely to experience fatal industrial accidents (Arocena & Nunez, 2010).

When industrial or occupational accidents and injuries take place, the costs incurred by SMEs are enormous. Not only they have to bear financial costs in terms of compensation pay-out, work-days lost, and productivity (Barling, Kelloway, & Iverson, 2003), they also have to face the non-financial consequences (Hrymak & Pérezgonzález, 2007). For instance, employees who are injured may suffer psychological trauma of coming back to work after recovery. The family members are also affected as a result of accidents and injuries at work. Other employees have to pick up the slack as a result of employee absence due to injuries, and they may also become traumatic as a consequence of the accident that has taken place. Because of these consequences, safety research is a crucial scientific activity.

Literature indicates that occupational accidents and injuries can be avoided if employees comply with safety standards, procedures, and regulations at work (Mearns, Flin, Gordon, & Leming, 2001). In order to promote safety compliance behavior, one of the factors that have been widely studied is safety management practices. However, studies that have considered the effect of the practices on safety compliance behavior tended to be conducted in large organizations which are likely to have a formal and structured OSH system. Because SMEs have many resource limitations, they are less likely to devote their resources toward implementing such as system (Champoux & Brun, 2003; Legg, Olsen, Laird, & Hasle, 2015). But, it does not mean that SMEs do not have a system of OSH at all; at best, their system may be informal and unstructured (Legg et al., 2015). Thus, it is intriguing to examine the degree of safety practices they have and whether these practices are able to encourage safety compliance of the employees. By doing so, the present study aims at contributing to safety research, particularly in SMEs, as studies in safety in SMEs are far and few between.

2. Literature review

Safety compliance is defined as adhering to safety procedures and carrying out work in a safe manner (Neal, Griffin, & Hart, 2000). Previous researchers have demonstrated that when employees follow safety rules and procedures, they are less likely to be injured or hurt in a workplace accident (Clarke, 2006; Neal & Griffin, 2006). By putting on safety equipment or using proper safety gear, the employees can protect themselves while at work, for example, resulting in fewer occupational accidents as a whole in the organization.

According to the management perspective in safety, occupational accidents are primarily the result of human error (Bottani, Monica, & Vignali, 2009), which can be reduced when employers institute a proper safety system (Gordon, Flin, & Mearns, 2005). Consistently, this perspective is in line with the Occupational Safety and Health Act 1994 which explicitly mandates that employers are responsible for ensuring the safety of the employees at work. The 1994 Act does not make an exception for employers, which means that employers in the SMEs are also covered by this Act. One way how this can be achieved is by instituting safety management practices, which refer to the safety-related approaches, policies, strategies, procedures, and activities implemented in the organization with the aim of reducing accidents and injuries at work (Díaz-Cabrera, D., Hernández-Fernaud, E.& Isla-Díaz, 2007; Vinodkumar & Bhasi, 2010). Based on Vinodkumar and Bhasi's work (2010), safety management practices are composed of many safety-related components. They are management commitment, safety training, safety rules and procedures, workers’ involvement, safety promotion policies, and safety communication and feedback.

Even though the OSH Act 1994 does not make an exception to any employers, SMEs may face significant challenges in instituting a comprehensive and structured OSH system. It is generally understood that SMEs tend to have a number of constraints, such as resources. Hence, their so-called safety system or practices are likely to be informal and unstructured (Champoux & Brun, 2003; Legg et al., 2015). It is against this backdrop that the role of safety management practices in promoting safety compliance behavior should be understood. Past studies on the role of safety management practices in fostering safety compliance in the context of SMEs are rather limited. Hence, we draw our argument from safety research conducted in different organizational contexts and milieus to help us with the hypotheses development.

2.1. Management commitment and safety compliance

There seems to be a general consensus that management commitment is critical to reducing occupational accidents at work (Vinodkumar & Bhasi, 2010). This is because management commitment reflects the seriousness of the management of safety-related issues, reflected in the attention and support given to the implementation of safety-related programs and projects in the organization (Hsu, Lee, Wu, & Takano, 2008). When management is committed toward safety, management is likely to be proactive in identifying, managing, and controlling hazards that are likely to result in accidents. When employees perceive that the management is committed to their safety, to their safety, they tend to take safety matters seriously, thus leading to an overall reduction in accident and injury rates (Yule, Flin, & Murdy, 2007). In the context of SMEs where lack of resources is likely to hinder them from putting in place a more formal and structured OSH system, management commitment towards safety is, therefore, a critical component of accident prevention and reduction. Some of the activities that SME employers can implement without incurring many costs include prioritizing safety over production, safety by walking around, putting and safety as an important agenda in the organization, etc. are. Hence, we propose the following:

H1: Management commitment is positively associated with safety compliance.

2.2. Safety training

The role of safety training in promoting safety behaviors among employees has been widely documented (Hare, Cameron, & Duff, 2006; Vinodkumar & Bhasi, 2010). When effective, safety training improves safety behavior, skills, and knowledge of employees. They are likely to be aware of potential hazards and risks at work and the likely consequences if the dangers are not heeded. While formal safety programs tend to have structured syllabus and activities for employees to engage in, carrying them out may eat up the SMEs’ budget. It has been argued that SME employers prefer to dedicate their resources to other things that have more productive value (Legg et al., 2015). In the context of SMEs, while sending employees to formal safety programs or carrying out internal and structured safety programs may not be the most feasible option given the resource constraints, informal and less structured training can be implemented on a daily basis. For instance, SME employers can dedicate some time for informal training sessions before the start of working day about safety issues. This, however, assumes that SME employers themselves have undergone some formal safety programs. Hence, we propose the following:

H2: Safety training is positively associated with safety compliance.

2.3. Worker involvement

In safety literature, worker involvement is defined as a behaviour-based technique which involves individuals or groups in an upward communication flow and decision-making process within an organization (Vredenburgh, 2002). In SMEs, worker involvement can be used as an essential tool for promoting safety compliance among employees. According to (Vredenburgh, 2002), since the employees are the ones who perform work tasks and activities, they are the best source of information for safety improvements at work. Due to the size of the organization, the employer-employee relationship tends to be less formal and more personal (Gooding & Wagner, 1985), which allows the employees to communicate directly their opinion and suggestions on matters related to safety to the management. It has been demonstrated that employee involvement in a decision-making process on issues that directly concern them tend to be more committed and receptive of the decision, leading to better job performance (Saks, 2006). It has been argued that when employees are involved in matters related to safety, they will have ownership of the solution, leading to reduced accidents and injury rates (Goetsch, 2008). However, for such practice to be effective in promoting safety behavior and compliance of employees, SME employers should value employee empowerment. Hence, we propose the following:

H3: Worker involvement is positively associated with safety compliance.

2.4. Safety communication and feedback

Safety communication and feedback has been recognized as an effective way of improving safety performance in organizations (Kines et al., 2010). Dissemination of information through various communication media, such as safety meetings, regular personal contacts, and sign posts, etc. on safety rules and regulations can serve as a reminder to employees of the need to be safety conscious and work safely (Comcare, 2004; Hopkins, 2002). But, to be effective, safety communication and feedback should be a two-way process rather than simply a top-bottom approach (Vinodkumar & Bhasi, 2010). Employees should also be encouraged to give their feedback on safety-related matters to the management and suggest ways of improving the work processes and activities that can be made safer. Safety feedback, whether it comes from the employer or employee, serves as a reinforcement tool for appropriate behavior modification (Prue & Fairbank, 1981). Hence, we propose:

H4: Safety communication and feedback is positively associated with safety compliance.

2.5. Safety rules and procedures

Safety rules and procedures refer to the degree to which an organization creates a clear mission, responsibilities, and goals, sets up standards of behavior for employees, and establishes safety system to correct workers’ safety behaviors (Lu & Yang, 2011). Even though employers have the legal duty to fulfill their duty of care (Hopkins, 2002), the OSH Act 1994 is silent on how employers should enforce it. Despite the absence of explicit legal provision, enforcing of safety rules and procedures reflect the management commitment toward safety at work (Fernandez-muniz, Mantes-peon, & Vazquez-ordas, 2007; Lu & Yang, 2011). In order to help employees understand the safety rules and procedures, and, hence, comply with them, the management has to make an effort in communicating the rules and procedures in a language that the employees can easily understand. Hence, we propose the following:

H5: Safety rules and regulations are positively associated with safety compliance.

2.6. Safety promotion policies

Safety promotion policies are policies that aim to ensure the presence and maintenance of conditions that are necessary to reach and sustain an optimal level of safety (Welander, Svanström, & Ekman, 2004). In order to promote and encourage employees to work safely and in a manner that does not endanger other people's wellbeing, the management can devise a number of strategies for the said purpose. Linking reward with safety performance is one approach that SMEs can use. Organizing programs to mark safety week and encouraging employees to report unsafe conditions are some of the ways SMEs can implement without significantly eating their financial coffers. Studies indicate that safety reporting by employees plays a crucial role in accident prevention at work (Barach & Small, 2000; Chen & Lai, 2014). In SMEs where employer-employee relationship tends to be personal and informal, employee reporting should be encouraged as long as it does not threaten the esprit de corps of the organization. The implementation of safety promotion policies reflects not only the management commitment toward safety, but it also signifies the proactive attitude toward safety. Indeed, studies have demonstrated the positive contribution of safety promotion and policies toward reducing workplace accidents and injuries (Ali, Abdullah, & Subramaniam, 2009; Vinodkumar & Bhasi, 2010). Hence, we propose the following:

H6: Safety promotion policies are positively associated with safety compliance.

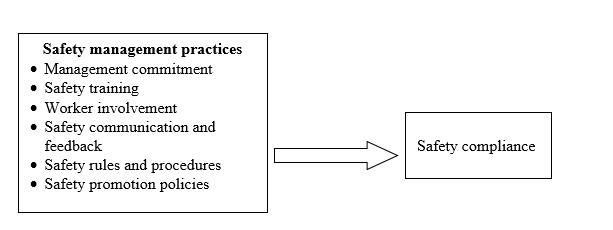

2.7. Proposed model

Figure

3. Conclusion

There is no doubt that safety at work is one of the major concerns of organizations, regardless of their size. However, ensuring safety at work among employees is one of the key challenges for small and medium enterprises. As that these organizations typically are argued to have a lack of resources, instituting a comprehensive and integrated OSH system is quite a daunting project. If such claim is valid, it should not mean that SMEs should not pay attention to aspects of safety at work. In this paper, we propose ways and means of how SMEs can address the safety concern without having to institute a formal and structured system. An examination on the safety management practices, composed of various elements, when implemented as a whole, are likely to help SMES to reduce occupational accidents at work. However, our propositions and speculations need to be empirically investigated as studies in safety in SMEs are quite limited. As such this proposed study would be one of the few studies that examine safety behaviour in the SME sector.

Acknowledgement

This paper has been supported by the Research Acculturation Grant Scheme under the Ministry of Higher Education of Malaysia

References

- Ali, H., Abdullah, N. A. C., & Subramaniam, C. (2009). Management practice in safety culture and its influence on workplace injury: An industrial study in Malaysia. Disaster Prevention and Management, 18(5), 470–477.

- Arocena, P., & Nunez, I. (2010). An empirical analysis of the effectiveness of occupational health and safety management systems in SMEs. International Small Business Journal, 28(4), 398–419.

- Aziz, A., Baruji, M., Abdullah, M., Him, N., & Yusof, N. (2015). An Initial Study on Accident Rate in the Workplace through Occupational Safety and Health Management in Sewerage Services. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 6(2), 249–255.

- Barach, P., & Small, S. D. (2000). Reporting and preventing medical mishaps: lessons from non-medical near miss reporting systems. British Medical Journal, 320(7237), 759–763.

- Barling, J., Kelloway, E. K., & Iverson, R. D. (2003). High-quality work, job satisfaction, and occupational injuries. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(2), 276–283.

- Bottani, E., Monica, L., & Vignali, G. (2009). Safety Management systems: Performance diferences between adopters and non-adopters. Safety Science, 47(2), 155–162.

- Champoux, D., & Brun, J.-P. (2003). Occupational health and safety management in small size enterprises: An overview of the situation and avenues for intervention and research. Safety Science, 41, 301–318.

- Chen, C., & Lai, C. (2014). To Blow or Not to Blow the Whistle: The Effects of Potential Harm, Social Pressure and Organisational Commitment on Whistleblowing Intention and Behaviour. Business Ethics: A European Review, 23(3), 327–342.

- Clarke, S. (2006). The relationship between safety climate and safety performance: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(4), 315–327.

- Comcare. (2004). Safe and sound: a discussion paper on safety leadership in government workplaces. Canberra, Australia.

- Díaz-Cabrera, D., Hernández-Fernaud, E.& Isla-Díaz, R. (2007). An evaluation of a new instrument to measure organisational safety culture values and practices. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 39, 1202–1211.

- Fernandez-muniz, B., Mantes-peon, J. M., & Vazquez-ordas, C. J. (2007). Safety Culture: Analysis of the causal relationship between its key dimensions. Journal of Safety Research, 38, 627–641.

- Goetsch, D. L. (2008). Occupational Safety and Health for Technologists,Engineers and Managers (6th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Education Inc.

- Gooding, R. Z., & Wagner, J. A. I. (1985). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between size and performance: The productivity and efficiency of organizations and their subunits. Administrative Science Quarterly, 30, 462–481.

- Gordon, R., Flin, R., & Mearns, K. (2005). Designing and evaluating a human factors investigation tool (HFIT) for accident analysis. Safety Science, 43, 147–171.

- Hare, B., Cameron, I., & Duff, A. R. (2006). Exploring the integration of health and safety with pre-construction planning. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 13(5), 438–450.

- Hopkins, A. (2002). Safety culture, mindfulness and safe behaviour: converging ideas?

- Hrymak, V., & Pérezgonzález, J. D. (2007). The costs and effects of workplace accidents Twenty case studies from Ireland. A report for Health and Safety Authority.

- Hsu, S. H., Lee, C. C., Wu, M. C., & Takano, K. (2008). A cross-cultural study of organizational factors on safety: Japanese vs. Taiwanese oil refinery plants. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 40(1), 24–34.

- Kines, P., Andersen, L. P. S., Spangenberg, S., Mikkelsen, K. L., Dyreborg, J., & Zohar, D. (2010). Improving construction site safety through leader-based verbal safety communication. Journal of Safety Research, 41(5), 399–406.

- Kongolo, M. (2010). Job creation versus job shedding and the role of SMEs in economic development. Journal of Business, 4(11), 2288–2295.

- Legg, S. J., Olsen, K. B., Laird, I. S., & Hasle, P. (2015). Managing safety in small and medium enterprises. Safety Science, 71, 189–196.

- Lu, C. S., & Yang, C. S. (2011). Safety climate and safety behavior in the passenger ferry context. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 43(1), 329–341.

- Mearns, K., Flin, R., Gordon, R., & Leming, M. (2001). Human and organizational factor in offshore safety. Work & Stress, 15(2), 144–160.

- Neal, A., & Griffin, M. A. (2006). A study of the lagged relationships among safety climate, Safety motivation, safety behavior, and accidents at the individual and group levels. Journal of Applied Psychology, 19(4), 946–953.

- Neal, A., Griffin, M. A., & Hart, P. M. (2000). The impact of organisational climate on safety climate and individual behaviour. Safety Science, 34, 99–109.

- Prue, D. M., & Fairbank, J. A. (1981). Performance feedback in organizational behavior management: A review. Performance Feedback in Organizational Behavior Management: A Review. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 3, 1–16.

- Saks, A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(7), 600–619.

- Salleh, A. S., & Ndubisi, N. O. (2006). An Evaluation of SME Development in Malaysia. International Reviewof Business Research Papers, 2(1), 1–14.

- SME Annual Report. (2014). SME Annual Report. (2013/2014).

- Surienty, L., Hong, K. T., & Hung, D. K. M. (2011). Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) in SMEs in Malaysia: A Preliminary Investigation. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 65–75.

- Vinodkumar, M. N., & Bhasi, M. (2010). Safety management practices and safety behavior: Assessing the mediating role of safety knowledge and motivation. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 42, 2082–2093.

- Vredenburgh, A. G. (2002). Organizational safety: Which management practices are most effective in reducing employee injury rates. Journal of Safety Research, 33, 259– 276.

- Welander, G., Svanström, L., & Ekman, R. (2004). Safety Promotion – an Introduction. Injury Prevention (2nd ed.). Stockholm,: Karolinska Institutet Department of Public Health Sciences.

- Yule, S., Flin, R., & Murdy, A. (2007). The role of management and safety climate in preventing risk-taking at work. International of Risk Assessment and Management, 7(2), 137–151.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

22 August 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-013-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

14

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-883

Subjects

Sociology, work, labour, organizational theory, organizational behaviour, social impact, environmental issues

Cite this article as:

Subramaniam, C., Shamsudin, F. M., Mohd. Zin, M. L., Ramalu, S. S., & Hassan, Z. (2016). Safety Management Practices and Safety Compliance: A Model for SMEs in Malaysia. In B. Mohamad (Ed.), Challenge of Ensuring Research Rigor in Soft Sciences, vol 14. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 856-862). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.08.120