Abstract

Relation with authority has been a relevant problem in times of change characteristic of the post-Soviet countries. A number of studies have stressed the importance of relation with authority in interpersonal relationships, psychosocial adjustment and well-being. The purpose of the current study is to explore the links between psychological well-being and relation with authority in three Lithuanian generations: young adults, who were born in independent Lithuania (aged 19-26); the middle generation, who have lived both under the Soviet occupation and in independent Lithuania (aged 27-49), and elderly persons, who have lived longer under the Soviet occupation (aged 50-70), 405 participants in total. The study used the Relation with Authority Scale (Grigutyte & Gudaite, 2015), the Well-Being Index (WHO, 1998) and the subjective ratings of how often the participants a) consumed alcohol, b) used antidepressants, c) had thoughts of suicide, d) turned to family members and friends or e) turned to mental health professionals for help. Results show that different aspects of internal and external relation with authority are important for higher psychological well-being in groups which vary in age and historical heritage. Psychological well-being is affected by self-esteem and is higher if: a) elderly persons, who have lived longer under the Soviet occupation, have more authorities; b) the middle generation, who have lived under the Soviet occupation and in independent Lithuania, have a less resistant relation with authority; c) young adults, who were born in independent Lithuania, rely more on transpersonal powers and have a less troubled relation with authority.

Keywords: Relation with authority, psychological well-being, independent Lithuania

Introduction

The history of Lithuania is rich and dates back to settlements founded many thousands of years ago, first mentioned in 1009 A.D. (Gudavičius, 1999). In the 13th century, the country was the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, later the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was created, following which up until the 20th century Lithuanians lived under the rule of the Russian Empire. In 1918, Lithuania was re-established as a democratic state. The country went through many dramatic political changes in the 20th century, including three occupations (the first Soviet occupation of 1940–1941, the Nazi occupation of 1941–1944 and the second Soviet occupation of 1944–1990). In 1990, Lithuania regained its independence and restored its sovereignty after 50 years of occupation.

The consequences of the authoritarian regimes had a fundamental impact on every person and every family; it is commonly viewed as a cultural trauma. People needed to survive the loss of family members and property, nationalisation and collectivisation, persecution and the destruction of church and religion (Kuodytė, 2005). Dangerous psychological strategies were employed in the face of the totalitarian system: deception of authorities and the system, secrecy, duplicity, passivity and change of identity were important survival strategies that could turn into destructive aggression and auto-aggression through self-deception (Gudaitė, 2014). Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and high prevalence of self-destructive behaviour, such as alcohol consumption and suicide, as well as the destruction of personal initiative, are also consequences of cultural trauma detrimental to the second and even third generations (Gailienė & Kazlauskas, 2005; Gailienė, 2015). Psychological research carried out ten and more years after the restoration of Lithuanian independence revealed that the consequences of the Soviet totalitarian regime, which lasted five decades, continue to be felt in the lives of both individuals and society as a whole to this day (Gailienė, 2015; Gudaitė, 2005).

Currently, Lithuania is undergoing a complicated transition from the authoritarian regime to democracy. The question of authority seems relevant at the time of any psychosocial transition when changing social structures require certain transformations of personality. The hypothesis that the Soviet system had a tremendous influence on the formation of personality with severe authority problems and a destroyed inner authority still needs to be explored. Despite the importance of the issue, there are not many studies on relation with authority and its manifestations in interpersonal relationships, psycho-social adjustment and psychological well-being.

Dieckmann (1977), a pioneer in the exploration of this theme in the post-soviet region, argues that the problem of authority lacks attention, though it is crucial in dealing with aggression and destruction. Authority rules not only the dimension of power, but those of reputation, prestige and wisdom as well. As authority always indicates a relation (Bochenski, 2004), the authority figure depends on those who acknowledge him or her. The relation with any authority figure is unique and changes as the person develops, yet there are general models of how a person reacts to authority: obeys or resists it, seeks authority; internalises it, projects it, idealises it, devalues it and searches for ways of authoring his or her own life. Relations with authority figures have a decisive influence on the development of inner authority. Inner authority is defined as the ability to value and validate one’s own thoughts, feelings, intuitions and perceptions leading to self-trust, confidence and the ability to become the author of one’s own life (Wertz, 2013), as well as the ability to influence and control the situation and react constructively to other authorities (Gudaitė, 2013).

Studies on cultural trauma in Lithuania reveal that individuals who lived under the authoritarian regime tend to view authority as a destructive and threatening power (Gudaitė, 2013). A troubled or hostile attitude toward authority is linked with traumatic experiences (Wirtz, 2014), causes negative experiences and may lead to various adjustment difficulties and a poorer psychological well-being. Well-being can be understood as how people feel and function, both on a personal and a social level, and how they evaluate their lives as a whole (Michaelson et al., 2012).

Purpose of the study

The purpose of the study is to explore the links between psychological well-being and relation with authority in three Lithuanian generations: young adults, who were born in independent Lithuania; the middle generation, who have lived both under the Soviet occupation and in independent Lithuania, and elderly persons, who have lived longer under the Soviet occupation.

Method

Participants

405 participants aged 19 to 70 were surveyed (24 % men and 76 % women). The participants represented three generations:

- 126 young adults born in independent Lithuania: 25 % men and 75 % women aged 19-26, with a mean age of 24;

- 213 representatives of the middle generation who have lived both under the Soviet occupation and in independent Lithuania: 24 % men and 76 % women aged 27-49, with a mean age of 35;

- 66 elderly persons who have lived longer under the Soviet occupation: 21 % men and 79 % women aged 50-70, with a mean age of 57.

Measures

Relation with Authority Scale (Grigutyte, Gudaite, 2015) was used to measure external and internal relation with authority. It is composed of 28 items rated on a five-point scale from to. The scale consists of five subscales which capture two broad dimensions of relation with authority, external and internal.

External relation with authority:

- Resistant Relation with Authority (e.g. “It is very important for me to prove my own truth” or “I tend to oppose others even if I do not benefit from it”); Cronbach α = .61.

- Troubled Relation with Authority (e.g. “I used to be afraid of my teacher’s sudden anger” or “I tend to pretend to be weaker so as not to take on responsibility”); Cronbach α = .73.

- Positive Relation with Authority (e.g. “I can relate with authority” or “My parents are (were) proud of me”); Cronbach α = .65.

Internal relation with authority:

- Self-Reliance (e.g. “I can influence other people” or “Many things in my life depend on me”); Cronbach α = .72.

- Reliance on Transpersonal Powers (e.g. “I feel that there are powers that protect me” or “Spiritual practices help me regain inner balance”); Cronbach α = .86.

A Principal Axis Factor (PAF) analysis with a Varimax rotation was conducted on the data. An examination of the Kaiser-Meyer Olkin measure of sampling adequacy suggested that the sample was factorable (KMO = .798) and Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant (p < .001). When loadings less than .30 were excluded, the analysis yielded a five-factor solution as indicated by the scale authors.

Psychological well-being was measured by:

- Well-Being Index (WHO, 1998), a five-item instrument which assesses the presence of aspects of well-being (e.g. mood, activity) over the last two weeks. Items are rated on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (at no time) to 5 (all of the time); Cronbach α = .85.

- Subjective ratings of everyday functioning evaluated on a five-point scale, from not at all to very often, which capture the following aspects: 1) how often one consumes alcohol as a means to suppress thoughts and feelings; 2) how often one uses antidepressants, sedatives or hypnotics; 3) how often in times of difficulty one thinks of suicide; 4) how often one turns to family members or friends when going through a hard time; 5) how often one turns to mental health professionals for help.

The study also used a demographic questionnaire on the participants’ gender, age, place of residence and education.

Results

4.1. Psychological Well-Being

Psychological well-being was assessed by the WHO-5 scale and subjective ratings of everyday functioning. The WHO-5 scale acts as a tool to measure how good the survey participants feel in everyday life. No statistically significant differences on WHO-5 scale ratings were found among the three groups (see Table 1).

Several subjective indices of everyday functioning vary among groups. Though participants of all the three generations turn to mental health professionals for help equally rarely, elderly persons use antidepressants, sedatives or hypnotics more often in comparison with the middle generation and turn to family members or friends when are going through hard times significantly less in comparison with the youngest group. It could be that young adults are still undergoing transition, are more attached to their families and have more friends than older ones. However, they use antidepressants or other medicines slightly more than the middle generation and think they could attempt suicide in times of difficulty significantly more often than both the middle generation and elderly persons.

4.2. Relations with Authority

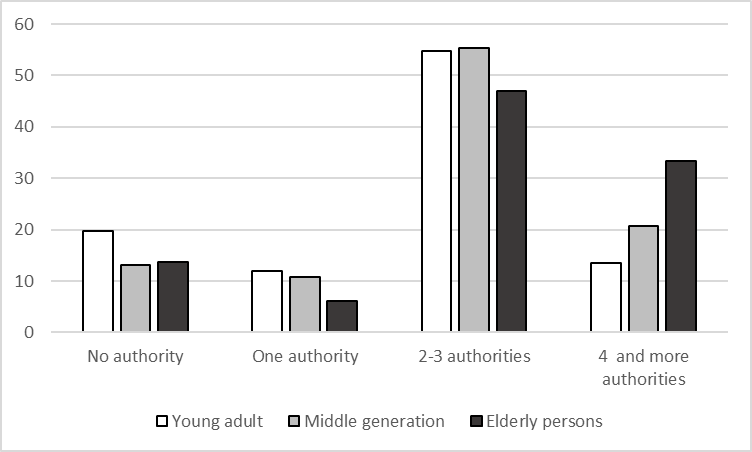

Most participants reported having two or three authorities (see Figure 1). The youngest group tended to have no authorities and the elderly tended to have four or more persons they could identify as their authorities. A weak correlation was found between the number of authorities and age (= .155, .01) and between the number of authorities and education (= .164,.01). It means that the older or the more educated an individual is, the more authorities he or she has.

The ratings of relation with authority were much the same in all the three groups, except for reliance on transpersonal powers. In regard to this aspect, statistically significant differences ( = 10.626; = 2; = .00) were found among all the three groups: young adults rely on transpersonal powers the least ( = 2.81; = 1.02), the middle generation – more ( = 3.22; = 0.98) and the elderly – the most ( = 3.4; = .81). Thus, the older the person gets, the more he or she relies on transpersonal powers (= .24,< .01).

Ratings of the external relation with authority show (see Figure 2) that most common among the participants is a positive relation and least common is a troubled relation with authority. Furthermore, there were no differences in ratings of self-reliance and reliance on transpersonal powers. But there were some gender differences found: men reported having a more resistant ( = 2.1; = 403; = .037) and a less positive ( = 2.91; = 403; = .004) relation with authority than women. Men are also more self-reliant ( = 2.67 = 403; = .008), but women rely on transpersonal powers more ( = 4.59; = 403; = .00).

4.3. Links Between Psychological Well-Being and Relation with Authority

The results show the link between psychological well-being and relation with authority. The more authorities participants have, the better they feel ( = .278, < .01), the more they turn to family members or friends in hard times ( = .164, < .01) and the less they think about suicide in times of difficulty ( = -.11, < 0.05). Correlations between psychological well-being and internal as well as external relation with authority within groups are shown in Table 2.

A resistant relation with authority is linked with consumption of alcohol as a means to suppress thoughts and feelings, but only in the middle generation. A troubled relation with authority is linked with all the indicators of psychological well-being, yet these associations differ within groups. The more troubled the relation with authority, a) the lower the index of well-being in all the three groups; b) the more often participants consume alcohol as a means to suppress thoughts and feelings, except for the young adults; c) the more often participants use antidepressants, sedatives or hypnotics, except for the young adults; d) the more common the thoughts of suicide in times of difficulty, except for the elderly persons; e) the more often the middle generation turn to mental health professionals for help; and f) the more often the oldest participants turn to family members or friends in hard times.

A positive relation with authority is linked with well-being index and turning to family members or friends in hard times, except for the elderly persons. What is more, positive relation with authority is associated with lower alcohol consumption for the oldest participants, lower use of antidepressants or other medicines for the middle generation and fewer suicidal thoughts for the young adults.

Self-reliance is linked with well-being index in all the three groups. Overall, higher self-reliance is associated with lower use of antidepressants and other medicines, fewer thoughts of suicide and a lower likelihood of turning to mental health professionals.

Lastly, the links between reliance on transpersonal powers and psychological well-being also vary among the three groups. The more the young adults rely on transpersonal powers, the better they feel and the fewer suicidal thoughts they have in times of difficulty. The more the middle generation rely on transpersonal powers, the more often they turn to family members or friends and mental health professionals for help. The more the elderly persons rely on transpersonal powers, the less alcohol they consume as a means to suppress thoughts and feelings.

4.4. Prediction of Psychological Well-Being

Since different correlations between psychological well-being and relations with authority were established for the three groups, a regression analysis was used to test if relations with authority significantly predicted participants’ psychological well-being within all the groups (see Table 3).

Three different regression models, one for each age group, were constructed. It was found that a troubled relation with authority and an internal relation with authority (self-reliance and reliance on transpersonal powers) significantly predicted well-being; these predictors explained about 35 percent of the variance in the youngest group. Regression analysis results for the middle generation group showed that three predictors explained 20 percent of well-being: the more self-reliant a person is, the more authorities he has and the less resistant his relation with authority is, the better his or her well-being will be. Self-reliance was the only aspect of relation with authority that together with the number of authorities explained more than 43 percent of the well-being data variance in the elderly group.

To sum up, self-reliance was the only aspect of relation with authority which predicted good well-being in all the three groups. A positive relation with authority was not a significant predictor in any group. A troubled relation with authority predicted poorer well-being only in the youngest group and a resistant relation with authority predicted poorer well-being only in the middle group. More relation with authorities in life may mean a better well-being for those people who were born and lived in the Soviet Union.

Discussion

The analysis of relation with authority has revealed that different aspects of internal and external relation with authority are important for the psychological well-being of people who differ in age and historical heritage. The results show that psychological well-being is influenced by the number of outside authorities and the quality of one’s relation with authority. The more relations with authority participants have, the better they feel, the more they turn to family members or friends in hard times and the less they think about suicide in times of difficulty. It appears that the number of relations with authorities is associated with social support, which is considered one of the most important factors for psychological well-being (Siedlecki et al., 2014).

An internal relation with authority, particularly self-esteem, also determines a person’s psychological well-being. A stable self-esteem appears to be a main determinant of psychological health. Psychotherapists note that an individual’s psychological growth is a gradual transition from reliance on the outside resources and support to the development of an inner support system (Perls, 1992). That is why an internalised constructive relationship with authority helps to form a stable self-esteem and, consequently, well-being of an individual. It was discovered (Gudaitė, 2016) that one criterion of the formation of inner authority is an individual’s ability to acknowledge and have respectful relationships with external authorities. We assume that it could be related to developmental factors such as development of identity. Unlike younger participants, elderly participants have developed the sense of identity; hence they accept their possibilities and limitations. Consequently, elderly people do not need to separate themselves from others by resisting or confronting them, which is typical for younger people. This well-developed sense of identity allows for acknowledgment of external authorities.

Research shows that people who have suffered from the Soviet regime tend to perceive authorities as dangerous and destructive (Gudaitė, 2013). Therefore, it could be beneficial for them to experience other relationships with authority which can instil in them feelings of safety, trust and hope that are paramount for an individual’s psychological well–being. As elderly people often encounter helplessness and external restrictions, they find themselves in an existential situation which makes them seek other sources of strength, such as connections with the transpersonal dimension. Numerous earlier studies found negative links between psychological well-being and age (Dhara & Jogsan, 2013; Steptoe et al., 2015); the results of the present study show that well-being is also associated with relation with authority: the more troubled the relation with authority is, the worse the elderly feel psychologically, the more antidepressants or other medicines they use and the less they turn to family members or friends for help.

Our findings also show that a resistant relation with authority is linked with poorer psychological well-being in the middle generation. These individuals have lived in two different regimes and are able to compare them. During the transition from the old to the new values and structures, people of this generation had to change the most. One previous study found that this generation evaluates changes mostly by how well they have managed to adapt (Bieliauskaite et al., 2015). In the Soviet regime, a formal relation with authority was more one-sided and defined through obedience, weakness and restrictions on freedom (Gudaitė, 2013). Personal initiatives and creative ideas were frowned upon and people could not be decisive and resist social norms (Lindy, Lifton, 2001; Lindy, 2001). Afterwards, the political and social situation has changed. It appears that the psychological well-being of people who have lived under the Soviet occupation and in independent Lithuania is better when they have a less resistant relation with authority and a stronger self-reliance. Perhaps they have fewer inner conflicts and a better adaptation without conflict projection. Conversely, individuals with an expressed resistant relation with authority could be more fixated on the stage of transition when confrontation with previous authorities was required to develop a new identity.

The young adults born in the independent state have to find new sources of spirituality, as for many of them the old forms are no longer relevant. Previous research also shows that the youngest generation give the most positive evaluation of the social and political changes that took place in Lithuania and have a much more negative view of the Soviet times (Bieliauskaite et al., 2015). On the basis of the developmental perspective it could be assumed that the youngest adults would have a resistant relation with authority. But it seems that a stable situation without any social upheavals in the country may be the reason for a less troubled relation with authority and a better psychological well-being. This could be confirmed by studies on psychological trauma indicating the relationship between a traumatising experience and a complicated relation with authority (Wirtz, 2014; Gudaitė, 2014).

The youngest generation stands out from the other two groups by the higher frequency of suicidal thoughts and their link with relation with authority. The more positive the young adults’ relation with external authority and the stronger their internal authority, the less they think about suicide in times of difficulty. These findings may be very important because the rate of suicide in Lithuania is very high, almost three times higher than the EU average: in 2010, the rate in Lithuania was 32.9 suicides per 100,000 people, whereas in the EU it was 11.8 (Lithuanian Department of Statistics, 2014). It could be argued that the level of suicidality is related to political situations and turning points in the country’s history (Gailienė, 2015), but this level continues to be high and it cannot be explained only by the impact of the earlier Soviet occupation. Probably many individuals of this generation still suffer from consequences of emotional and even physical abandonment as their parents had to struggle hard to survive during economic changes; besides, emigration opened a whole new spectrum of psychological problems for their children.

In summary, relation with authority is important for an individual’s personal development and for the society at large in times of transition from an authoritarian regime to democracy. At any stage of development, one’s relation with authority includes connections with important people, social structures and transcendental forces that are also shaped by culture, history and an individual himself. Inasmuch as in the post-Soviet space authority is associated with the authoritarian regime and the repressive influence on an individual, he has a task to liberate himself from a suppressing authority image and to develop the feeling of inner authority. Our findings show that an individual’s relation with authority affects his self-esteem, destructive or constructive coping behaviours and psychological well-being.

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by a grant (No. MIP-080/2014/LSS-250000-488) from the Research Council of Lithuania.

References

Bieliauskaitė, R., Grigienė, D., Eimontas, J., & Grigutytė, N. (2015). Evaluation of Changes Brought About by Independence on Three Generations in Lithuania. In D. Gailienė (Ed.) Lithuanian Faces After Transition: Psychological Consequences of Cultural Trauma. Vilnius: Eugrimas, 48-85.

Bochenski J.M. (2004). Kas yra autoritetas? Įvadas į autoriteto logiką. Vilnius: Mintis.

Dhara, R. D., & Jogsan, Y. A. (2013). Depression and Psychological Well-being in Old Age. Journal of psychology and psychotherapy, 3:117.

Dieckmann, H. (1977). Some aspects of the development of authority. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 22(3), 230-242.

Gailienė, D. (2015). Trauma and Culture. In D. Gailienė (Ed.) Lithuanian Faces After Transition: Psychological Consequences of Cultural Trauma. Vilnius: Eugrimas, 9-23.

Gailiene, D., & Kazlauskas, E. (2005). Fifty Years on: The Long-Term Psychological Effects of Soviet Repression in Lithuania. In D. Gailiene (ed.), The Psychology of Extreme Traumatization. The Aftermath of Political Repression. Vilnius: Genocide and Resistence Research Centre of Lithuania, 67-107.

Grigutytė, N., & Gudaitė, G. (2015). Construction and Development of the Questionnaire Assessing the Relation with Authority. Poster presented at the 14th European Congress of Psychology, Milan, Italy.

Gudaitė, G. (2016). Santykis su autoritetu ir asmeninės galios pajauta. Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla.

Gudaitė, G. (2014). Restoration of Continuity: Desperation or Hope in Facing the Consequences of Cultural Trauma. In G. Gudaitė & M. Stein (Eds.), Confronting Cultural Trauma: Jungian Approaches to Understanding and Healing. New Orleans [La.]: Spring Journal Books, 227-242.

Gudaitė, G. (2013). The dynamic of authority images in the context of consequences of collective trauma. In E. Kiehl (Ed.), Copenhagen 2013: 100 Years on: Origins, Innovations and Controversies: Proceedings of the 19th Congress of the International Association for Analytical Psychology. Daimon Verlag, 340-349.

Gudaitė, G. (2005). Psychological Afterefects of the Soviet trauma and the Analytical Process. In D. Gailiene (ed.), The Psychology of Extreme Traumatization. The Aftermath of Political Repression. Vilnius: Genocide and Resistence Research Centre of Lithuania, 108-126.

Gudavičius, E. (1999). Nuo seniausių laikų iki 1569 metų. Lietuvos istorija. T. 1. Vilnius.

Kuodyte, V. (2005). Traumatising History. In D. Gailiene (ed.), The Psychology of Extreme Traumatisation. The Aftermath of Political Repression. Vilnius: Genocide and Resistence Research Centre of Lithuania, 13-25.

Lindy, J. D. (2001). Legacy of Trauma and Loss. In J. D. Lindy, R. J. Lifton (eds.), Beyond Invisible Walls: The Psychological Legacy of Soviet Trauma. New York: Brunner-Routledge, 13-35.

Lindy, J. D., & Lifton, R. J. (2001). Introduction. In J. D. Lindy, R. J. Lifton (eds.), Beyond Invisible Walls: The Psychological Legacy of Soviet Trauma. New York: Brunner-Routledge, 1-12.

Lithuanian Department of Statistics (2014). Source: http://www.stat.gov.lt/en/

Michaelson, J., Mahony, S., & Schiffers, J. (2012). Measuring Well-being. A guide for practitions. The New Economics Foundation. Source: http://b.3cdn.net/nefoundation/8d92cf44e70b3d16e6_rgm6bpd3i.pdf.

Perls, F. S. (1992). Gestalt Therapy Verbatim. Gestalt Journal Press.

Siedlecki, K. L., Salthouse, T. A., Oishi, S., & Jeswani, S. (2014) The Relationship Between Social Support and Subjective Well-Being Across Age. Social Indicators Research, 117(2), 561-576.

Steptoe, A., Deaton, A., & Stone, A. (2015). Psychological wellbeing, health and ageing. Lancet, 385(9968): 640-648.

Wertz, K. (2013). Inner Authority and Jung‟s Model of Individuation. Source: http://jungiantrainingboulder.org/365/

Wirtz, U. (2014). Trauma and Beyond: The Mystery of Transformation. Spring Journal.

World Health Organization info package: Mastering depression in primary care. (1998) Frederiksborg: World Health Organization, regional Office for Europe Psychiatric Research Unit. Source: http://www.psy-world.com/who-5.htm.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 July 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-012-9

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

13

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-462

Subjects

Health psychology, psychology, health systems, health services, ocial issues, teenager, children's health, teenager health

Cite this article as:

Grigutytė, N., & Rukšaitė, G. (2016). Lithuanian Historical Heritage: Relation with Authority and Psychological Well-being. In S. Cruz (Ed.), Health & Health Psychology - icH&Hpsy 2016, vol 13. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 274-284). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.07.02.27