Abstract

Problem Statement: The child builds her own Depictions on the process of life and death with a background of life experiences. The connotations and feelings built by children about this process are determined by their developing state and naturally influenced by the education given by both parents and the society. Research Question: What is the predominant Depiction of death in children from 5 to 10 years old? Purpose of the Study: Analyse the Depiction that children have about death. Research Methods: The transversal and descriptive study was made on a sample of 175 children living in Portugal, 50.29% of the children were boys and 49.71% were girls with ages comprehended between 5 and 10 years old (M=7.69years). Findings: Most of the children pledges that after death people go to hell or heaven (49.7%); they distinguish the death of people from the animal one, 51.4% state that nothing happens after death; they think that they won't feel any pain on the moment of death 52.6%, a majority on the age group 7 to 8 years, when it comes to dolls 89.7% of the children say that they don't die; 64.8% never went to a funeral, 36% don't know which is the colour of the casket and 61.7% pledges not to know what it means to grief someone; the irreversibility parameter is a majority on the age group >=9 years. Conclusion: The children take influence from the culture in which they live and from death experiences that they live. The results showed that their perception changes according to their developing stage.

Keywords: Death, child, life experiences

Introduction

The child builds her own Depictions on the process of life and death with a background of life experiences. The connotations and feelings built by children about this process are determined by their developing state and naturally influenced by the education given by both parents and the society. Death is a matter viewed as “taboo” and as such, usually there are no opportunities to talk about the process of death in the family.

To understand the depiction of death in children implies consideration of the state of their development, listen to their stories about the experiences that they have lived through, get to know their own construction on events related with the process of life and death, the funeral and bereavement. It is also important to observe and to interpret their drawings, exploring their graphic depictions on death, their conceptions and experiences.

Problem statement

“…The death of someone, the death of anyone, being a natural event is not a trivial occurrence, it´s never trivial. The natural end to my life, my death is for me, like being conscious, the most important event in my life; by its being finite, by being limited in time, that the life of an individual has the enormous value which we all attribute to it. To live for a limited time is a great challenge, it guides our wishes and our choices, it makes us hurry towards a goal which we can´t see but which we know is certain to be true, that it is our point of no return from the invisible frontier, between being alive and being dead.” (Daniel Serrão, 1990 cit. in Cunha et al, 2003, p.33).

In spite of the universality of death, people in the west consider it to be a phenomenon which fits into a negative scenario of fear, to which are added feelings of loss, anguish and rejection (Parijs, 2011). A product of this image and the contact which children have with death is something which, in accordance with the predominant culture, should be avoided. The child frequently will have access prevented to people who are ill or dying which results in a brake on the understanding of these processes and the subsequent changes which are caused at the heart of the family (Aries, 1977 cit. in Almeida, 2005, p.150).

By omitting the reality surrounding death, adults feel that protecting the children, easing their pain in the meantime does not change the reality while producing a feeling of confusion and being unprotected. Discussing and demystifying the matter would be much more beneficial to the child (Kovács, 1992, p.49 cit. in Vendruscolo, 2005, p.27).

In the specific instance of children living through the process of grieving, contributions from psychoanalysis demonstrate that they live through this process although they are not always able to verbalize it. In the coverage of infant – young mourning, there are certain beliefs arising from common sense which make it difficult to distinguish between the myth and reality (Andrade & Barbosa, 2010 cit. in Cunha et al, 2015, p.18). It is therefore important that family are present and support the children while preventing the regular progress of the grieving process (Aberastury, 1984, cit. in Domingos & Maluf, 2003, p.577-578). In order to aid the healthy completion of the grieving process, when the death takes place and taking into account the development of the child, it should be explained what has happened, avoiding the hiding of anything and untruths, preventing the adverse effects which may result from the experience of a prolonged grieving process (Gauderer, 1987 cit. in Anton & Favero, 2011, p.103)

Speece and Brent (1984), cit. in Nunes, et al (1988), set out three parameters which are essential for an understanding of the depiction of death for the child which are: irreversibility, non-functionality and universality. Irreversibility refers to the understanding that when someone dies they cannot come back to life and is a permanent condition. Non-functionality is linked to the understanding that vital functions end on death and universality is the concept that all living beings die and that it is an inevitable situation.

Taking into account the three above-mentioned concepts, Nagy, 1959, cit. in Torres, 1980, cit. in Nunes, et al (1988), describe three developmental stages in the evolutionary construction of the concept of death. The first being up to 5 years, where there is no concept of final death, it is understood as a separation, a dream or something temporary. In the second stage between the ages of 5 and 9 there is a tendency for personification and death is conceived as “someone” who comes to collect people, at this stage understood as irreversible but also inevitable. In the third stage, from 9 to10 years, the three parameters have already been internalized by the child who recognizes death as being irreversible and the cessation of the activities of the body and comes to accept it as inevitable. However, only during the adolescence period, the meaning of life and the understanding of death is fully conceptualised.

In some research carried out in this field, and taking the infant drawing as a basis, it was possible to find graphic depictions of the various states and the three stages of understanding of death. Speece and Brent, (1984), cit. in Nunes, et al (1988), carried out a study with 6 children aged from 6 to 7 years on their understanding of death. In the results it was found that the older children had a more developed conception of death. The authors also saw that what was brought to them by television or close family members also drives a more detailed conception of death, regardless of the cognitive age. The research also raised important questions such as how the development of this conception may be linked not only to the cognitive age but also to close experiences of death.

Research questions

What is the predominant depiction of death in children from 5 to 10 years old?

Purpose of the study

Analyse the depiction that children have of death.

Research methods

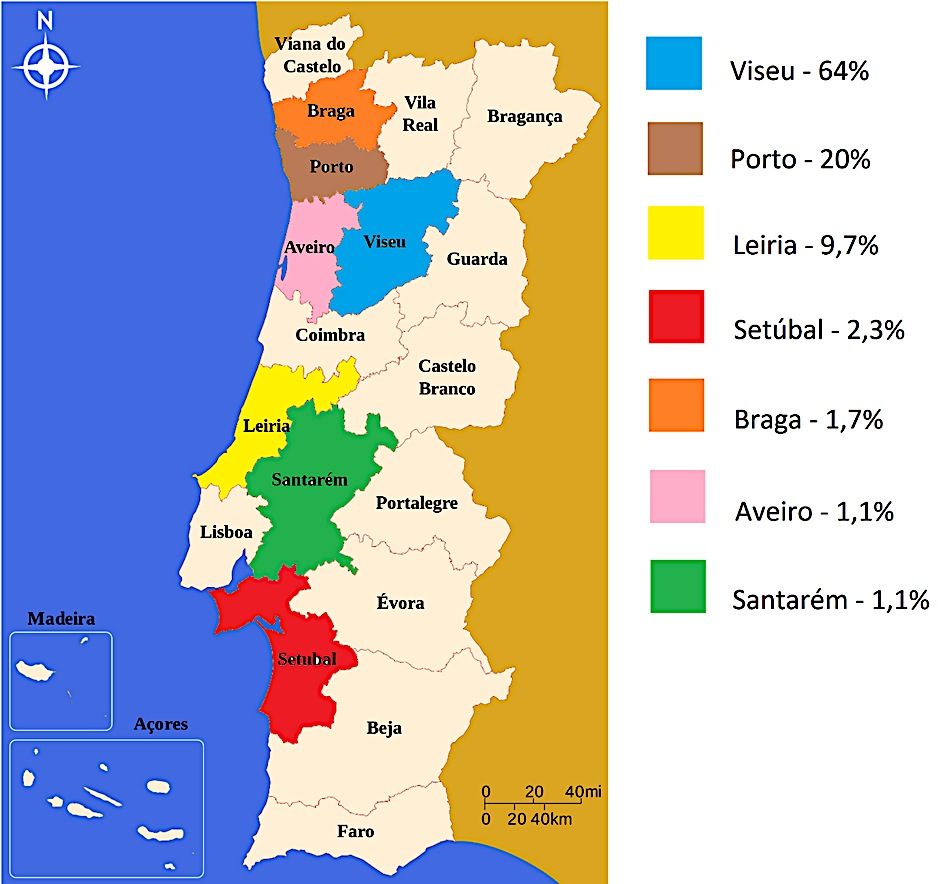

This transversal and descriptive study was made on a sample of 175 children living in Portugal, 50.29% of the children were boys and 49.71% were girls with ages ranged between 5 and 10 years (M=7.69 years). Area of residence: Urban (65.14%); Religion/Doctrine: Catholic (89.72%).

Findings

6.1 Depiction of death by children

It was found that 49.7% of the children are of the opinion that after death people go to either heaven or hell, the largest percentage being males (25.1%) and aged between 7 and 8 years (20%). It was also found that 51.4% of the children are of the opinion that after the death of animals, the same does not happen to them as to humans, being 54.7% female and 48.3% male and in the age group >=9 years (19.7%). This result is in line with the findings of Mendes (2009) cit. in Pedro et al (2011, p.7), where it is stated that the concept of death is intimately linked to the culture and its rituals.

On the other hand, 89.7% of the children are of the opinion that dolls don´t die, being 90.9% of males and 88.4% females in the 7 to 8 years age group (34.5%). Domingues, (1996) cit. in Almeida, (2005, p.150), stating that the prospect of death is not always influenced by the loss of a pet animal or a broken toy.

The majority (52.6%) of the children stated that people do not feel pain on their death, with the largest percentage in the 7 to 8 years age group (24.9%). The chi-square test showed significant differences for variation compared to the children´s age groups (Chi-square=5.899; p=0.052), the adjusted residuals also indicate a significant difference in the age group between 7 and 8 years in comparison with other groups or, in other words, it is the children in the 7 to 8 age group who have a more unanimous and relevant opinion about what happens after death compared with the remainder.

6.2 Graphic Depiction / Drawings of death

An overall analysis of the drawings showed that:

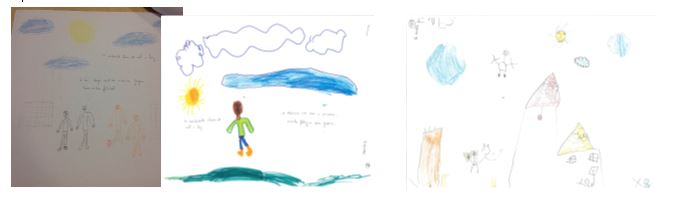

6.2.1 Groups from 5 - 6 years

In the children´s drawings there are hardly any depictions of dead people. There are children who are in hell because they behaved badly; or in heaven strolling, or because they behaved well. In this age group the children use bright colours; they draw people in hospital; depiction of a coffin with arms and legs; churches are depicted; people who have become stars in the sky. There are numerous drawings with symbols linked to religion including

The children in this age group clearly have not acquired certain cognitive conceptions of death.

The question of irreversibility does not appear, while on the contrary, the people are not dead or are in hospital as they also appear as having been transformed into stars playing in the sky or in hell being punished.

Depiction of death – Age group from 5 - 6 years

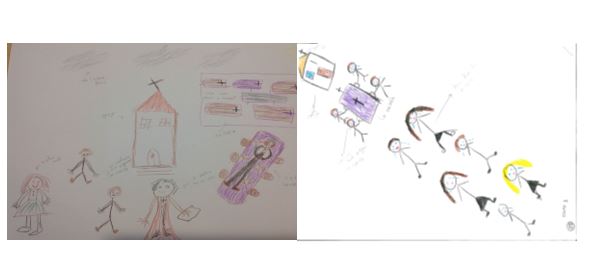

7 - 8 years age group

Overall, all of the drawings are closely linked to religious symbolism, including: depictions ofalthough they are not always present, fulfilling the three parameters of irreversibility, non-functionality and universality. In many of the drawings there are people shown to be in hospital, people who have been transformed into angels, living among the clouds (heaven), in a coffin but laughing. In some drawings there is no depiction of people, there appearing to be a denial of the potential for people to die: aspects of the social rituals of the funeral are also shown including the flowers, people weeping and crosses.

There is an evolution in relation to the drawings of the previous group. People are depicted inside coffins, under the ground and lying still.

9 - 10 years age group

The drawings are still closely linked to religious concepts with a notable evolution in relation to the previous group. Various forms of causing death are depicted including pistols, the guillotine, disease, depictions of forms of death which do not feature in any of the other groups. Some of the signs of non-functionality of death are also featured, the depiction of a dead person in a cemetery without any features being shown. Sadness is also shown much more with people weeping, wearing dark clothing, with sad expressions on their faces.

Analysis of the drawings shows that the children which are in pre-operational states of cognitive development (2 – 7 years) and the concrete – operational state (7 – 11 years old), do not produce drawings which translate the irreversibility of death, while from the age of 7 those irreversibility begins to feature.

Irreversibility is shown mostly in the drawings of male children (36%) and the age group > = 9 years (25.7%). Non-functionality is present in the majority of the 7 to 8 years age group, being more prevalent in males (29.1%). Universality became patent in the drawings of 34.9% of male children and in the >= 9 years age group.

There are statistically significant differences in children in the >= 9 years of age group in relation to the children in other age groups for the irreversibility parameter which implies that the children in this age group are more cognitively developed in comparison with the others.

Drawings by the 9 to 10 years age group express the three parameters described by Speece and Brent, translating a greater cognitive development. These results are in agreement with those of Nunes et al (1988) where the older children have a more developed conception of death which itself may be affected by a range of educational and social factors.

In children’s drawings there is a tendency towards personification, where death is perceived as being who comes to find people, which show that children believe that death is able to be avoided. This perception occurs in children between 5 and 9 years of age. Children between 9 and 10 years of age are aware of the ceasing of activity in human body and see death as being an inevitable event. These results are in line with the suppositions of Nagy (1959) and Torres, (1980) cit. in Nunes, et al (1988).

Conclusions

The majority of children stated that they had never visited a cemetery, had never taken part in a wake or a funeral and showed themselves to be unaware of the rituals associated with death. However, the majority have aof death where they believe that there are mythical figures responsible for the deceased after their death.

It is therefore inferred that the children receive influence from the culture in which they live and from death experiences that they live through. The results showing also, that their perception changes according to their stage of development.

Acknowledgements

CI&DETS, Superior School of Health of the Polytechnic Institute of Viseu.

References

Almeida, F. A. (2005). Lidando com a morte e o luto por meio do brincar: A criança com cancer no hospital. Boletim de Psicologia de São Paulo, 55(123), 149-167. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/bolpsi/v55n123/v55n123a03.pdf

Anton, M. C., & Favero, E. (2011). Morte repentina de genitores e luto infantil: Uma revisão da literatura em periódicos científicos brasileiros. Interação Psicológica, 15(1), 101-110. Doi: DOI:

Cunha, M., Dias, A. & Nelas, P. (2003). Cuidados pós-mortem. Sinais Vitais, 46, 33-39.

Cunha, M., Teixeira, A. R., Gomes, A., Oliveira, E., Martina, J., Sequeira, J., … Bica, I. (2015). Mitos sobre o luto em crianças e adolescentes. In I Jornadas de Investigação (pp. 18). Castelo Branco: Associação Portuguesa de Cuidados Paliativos.

Domingos, B., & Maluf, M. R. (2003). Experiências de perda e de luto em escolares de 13 a 18 anos. Psicologia: Reflexão e Critica, 16(3), 577-589. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.br/pdf/prc/v16n3/v16n3a16.pdf

Nunes, D. C., Carraro, L., Jou, G. I., & Speeb, T. M. (1998). As crianças e o conceito da morte. Psicologia, Reflexão e Crítica, 11 (3), 579-590. Doi: DOI:

Parijs, Z. (2011, Abril 9). Como explicar a morte às crianças. Jornal de Notícias. Retrieved from http://www.jn.pt/blogs/emletramiuda/archive/2011/04/09/como-explicar-a-morte-224-s-crian-231-as.aspx

Pedro, A., Catarina, A., Ventura, D., Ferreira, F. & Salsinha, H. (2011). A vivência da morte na criança e o luto na infância (Trabalho realizado na disciplina de Psicologia Clínica e da Saúde do 3º ano de Licenciatura em Psicologia, Universidade Lusófona de Humanidade e Tecnologia de Lisboa). Retrieved from http://www.psicologia.pt/artigos/textos/TL0226.pdf

Vendruscolo, J. (2005). Visão da criança sobre a morte. Medicina, 38 (1), 26-33. Retrieved from http://revista.fmrp.usp.br/2005/vol38n1/3_visao_crianca_sobre_morte.pdf

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 July 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-012-9

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

13

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-462

Subjects

Health psychology, psychology, health systems, health services, ocial issues, teenager, children's health, teenager health

Cite this article as:

Cunha, M., Costa, C., Silva, F. J. D., Barbosa, F., Aparício, G., & Campos, S. (2016). Representation of death in children. In S. Cruz (Ed.), Health & Health Psychology - icH&Hpsy 2016, vol 13. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 171-178). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.07.02.15