Abstract

In this study, we used the method of differentiated instruction. By using the differentiated instruction in physical education lessons for pupils with visual impairments, we intend to determine if progress can be made in terms of speed development. The study addresses to subjects with visual impairments enrolled in special schools, among which we find both blind and visually impaired pupils. The grades to which we refer are part of lower secondary school, one fifth grade and two sixth grades. An initial testing was conducted, which targeted the assessment of reaction speed, arm repetition speed and running speed. For speed, we used the Stopwatch test, for repetition speed, we used Plate Tapping from Eurofit Test Battery, and for running speed, we used 5x5 Shuttle Run from the National School Assessment System for Physical Education and Sports. After applying the tests, the value I and II groups were established for each grade involved in the experiment. After completing the instruction program, the pupils were assessed again using the tests from the initial testing. The analysis of the results showed an improvement in terms of speed for the visually impaired pupils due to the use of differentiated instruction.

Keywords: Physical education lessons, visually impaired, blind, differentiated instruction, speed

Introduction

School physical education, through the variety of practical means and the complexity of theoretical

aspects required, offers a vast field of research for the specialists. There is an increase in their interest

in training people with disabilities. But the issue related to the motor development of visually impaired

people is nowadays considered insufficiently addressed, if we look at to the figures that show an

increase in the number of national and worldwide visually impaired people during the last decades.

Including individuals with visual impairments, physical activity not only provides the benefits of

increased physical stamina and fitness, but also improves self-esteem, perception of one’s own

competence, one’s sense of autonomy, and relationship skills (Lieberman, Ponchillia, & Ponchillia, 2013: 5).

The achievement process of a high quality educational system for people with visual impairments

covers all the components of training and education: structure, content, forms of organization, methods,

means and evaluation. In order to accomplish this objective, it is necessary to improve the educational

activities, and a main condition of continuous improvement is represented by the adoption, but also

adaptation of the elements already mentioned to the individual particularities of the pupils. Our interest

in this direction can be explained by the fact that, only through a better knowledge of the subjects’

particularities, it is possible to have a proper development of the motor skills. In this regard, three

variables found to affect the physical fitness performance of visually impaired youngsters are the

severity of visual impairment, gender and age (Winnick, 1985: 292).

After knowing these particularities, a means that can be successfully applied during the entire

educational practice is the differentiated instruction. In physical education, one of the virtues of

differentiated instruction involves conducting the instruction and education process according to the

biomotor potential of the pupils. For the visually impaired pupils, this requires knowing the ophthalmic

deficiency, but also being aware of how these problems affect each person individually, functionally,

physically or morphologically.

Subsequent to this knowledge, the efficiency of the method can be known through direct use in the

physical education lesson, at the level of all components of the motor ability. In differentiated

classrooms, teachers provide specific ways for each individual to learn as deeply as possible and as

quickly as possible, without assuming one pupil’s road map for learning is identical to anyone else’s

(Tomlinson, 1999: 2). In order to achieve the objectives, even if there is a lack of biomotor

homogeneity (in our case) in the groups, the physical education teacher appeals to conduct the activity

with differentiated groups according to each pupil’s biomotor potential criterion (Șerbănoiu & Tudor,

2007: 109).

There are many strategies that invite teachers to look at the needs of small groups and individuals,

as opposed to strategies that encourage teachers to teach as though all learners share the same readiness

level, interests and modes of learning (Tomlinson, 1999: 75), and also practice in our field.

Through this research, we aimed at the progress recorded in the case of three manifestation forms of

speed. Speed is the ability to perform acts or actions with full body or only certain parts of the body in

the shortest time possible, so with maximum potential, depending on the circumstances (Cârstea, 1993:

46). We consider that the developing of any motor quality also improves the autonomous life of the

subjects, and therefore speed development has positive effects in this direction.

Materials and methods

This experimental research regarding speed development in pupils with ophthalmic deficiency using differentiated instruction was conducted during 2014-2015 school year and targeted the following

stages: applying the initial assessment, establishing the experimental groups, dividing the pupils from the experimental groups into value groups, conducting the differentiated activity depending on the

value groups and applying the final testing to assess speed.

Purpose of the research

The aim of this study is to streamline the physical education lessons addressed to manifestation

forms of speed, as reaction speed, repetition speed or running speed, for the 5th grade and 6th grade, containing visually impaired pupils.

Hypothesis

In physical education lessons, the use of differentiated instruction according to the motor potential

and ophthalmic deficiency of the pupils suffering from visual impairment and blindness, in the 5th and 6th grades, will determine an improvement of their performances as regards the three manifestation

forms of speed.

Participants and place

The subjects involved in this study are pupils with visual impairments from lower secondary

education, namely in the 5th and 6th grades at the Special Secondary School in Bucharest. For the 5th A grade, 6th A grade and 6th D grade, the compared results are represented by the performances in the

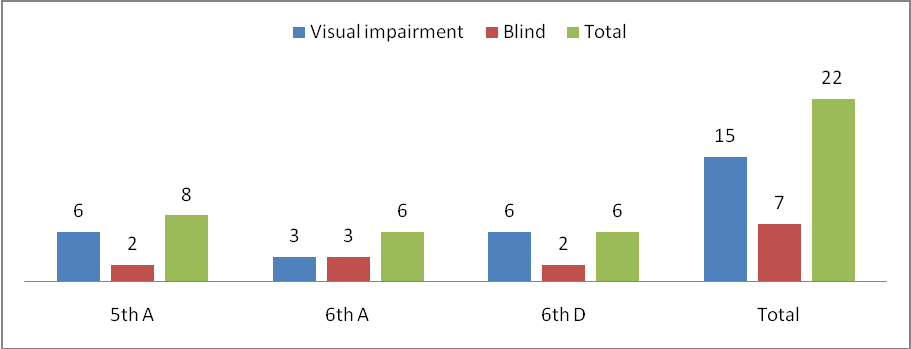

initial and final testing. The classrooms are mixed, in terms of ophthalmic deficiency, as well as from the point of view of the gender. Thus, within the same classrooms, one can find together pupils with visual impairment and blindness. The study was made on 22 pupils, 7 suffering from blindness and 15 suffering from visual impairment (Fig. 1).

In terms of associated disorders, we mention that there are subjects with different diagnostics, but

also subjects without associated disorders, as follows: •5th A: 2 pupils show no associated disorder, while the others present different pathologies – carential anaemia, enuresis, systolic murmur grade 3, congenital pulmonary stenosis, spasmophilia,

atresia and stenosis ureteropelvic junction, unilateral weakness weight; 2 subjects are not allowed to participate in physical education lessons, because of their diagnostics - spastic tetraparesis; •6th A: 4 pupils show no associated disorder, but there are cases of epilepsy and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in the classroom; •6th D: 4 subjects show no associated disorder, while other 4 subjects in the classroom present attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), spastic left hemiparesis, depressive disorder, chronic

vocal tic, mild mental retardation.

Research methods

During this research, we used as methods: directed observation, experiment and statistical indicators – mean, standard deviation and coefficient of variance.

Tests used in the research

The initial and final tests used in this study are represented by Plate Tapping, Stopwatch, and 5x5

Shuttle Run. We mention that these tests were applied to all three experimental classrooms.

Plate Tapping was applied in accordance with the original test from Eurofit Battery, but with certain

requirements related to the particularities of visually impaired pupils, meaning that for pupils suffering

from amblyopia, the plates had stronger colour allowing faster identification, and the pupils suffering

from blindness were allowed a longer period of practice before performing the test, for having a better

representation of the distance between the plates.

The Stopwatch test involves starting and stopping as fast as possible the stopwatch using the thumb,

for both hands. The assessment does not require adaptation for visually impaired pupils.

The 5x5 Shuttle Run test (National School Assessment System for Physical Education and Sports

from Romania) will be adapted, in terms of a strict delimitation of the distance with more bulky and

colourful objects, or pupils with bell rings, for a better spatial orientation of the subjects with blindness.

Blind pupils will benefit from assistance from the teacher or other colleagues with remnants of light,

meaning that they will be lead in advance each time in order to improve their topographical

representation.

Content of the research

During the lesson, the experimental classrooms worked by value groups resulted from the initial

assessment, in accordance with the motor potential and ophthalmic deficiency of the pupils. Value

groups had a closed character, which did not allow the pupils to migrate from one group to another

while running the instruction program. The division into value groups was made according to the

obtained performances and to the assessment scale shown in Table 1.

According to the scale, the performances were converted into points, which determined the value

group in which each pupil of the experimental group was distributed. The split was possible after

calculating the mean of the points obtained for speed: value group I (40-21) and value group II (20-0).

Within the physical education lessons, different measures were taken regarding the instruction and

education process. In this regard, we refer to the two parameters of effort: size and orientation.

According to them, the tasks that the pupils had to perform were different from one value group to

another:

•Value group I – characterized by an increase in the intensity of effort, by conducting various exercises structures by decreasing the volume of effort;

•Value group II – characterized by a decrease in the intensity of effort, by conducting standard exercises by decomposition of some movements.

These different tasks that the subjects had to perform did not represent anything else but the result

of analysis of the differences between individual particularities of each pupil included in this research.

Results

Data recorded in the initial and final assessments allowed us to perform an analysis of the number of

subjects, in accordance of the value group in which they were included, as follows (Table 2):

Table 3 shows the results obtained by visually impaired pupils at the initial and final assessments.

The Stopwatch test was assessed in hundredths of a second. For the Plate Tapping and 5x5 Shuttle

Run, the time was recorded in seconds. Comparing the initial and final assessments, we concluded the

following: •5th A: the average performance decreased by 3 points from the initial assessment to the final assessment at Stopwatch test on right thumb, by 3.2 points at Stopwatch test on left thumb, by 3.9

seconds at Plate Tapping, and 1.4 seconds at 5x5 Shuttle Run test. The value of the significance test is

0.004 for Stopwatch test on right thumb, 0.005 for Stopwatch test on left thumb, 0.01 for Plate

Tapping, and 0.01 for 5x5 Shuttle Run test. We can observe that all values are smaller than the

significance threshold at p< 0.05.

•6th A: the average performance decreased by 1.8 points from the initial assessment to the final assessment at Stopwatch test on right thumb, by 6.6 points at Stopwatch test on left thumb, by 2.3

seconds at Plate Tapping, and 2 seconds at 5x5 Shuttle Run test. The value of the significance test is

0.01 for Stopwatch test on right thumb, 0.04 for Stopwatch test on left thumb, 0.008 for Plate Tapping

and 0.003 for 5x5 Shuttle Run test. We can observe that all values are smaller than the significance

threshold at p< 0.05.

•6th D: the average performance decreased by 4.8 points from the initial assessment to the final assessment at Stopwatch test on right thumb, by 6.6 points at Stopwatch test on left thumb, by 1.5

seconds at Plate Tapping, and 1 second at 5x5 Shuttle Run test. The value of the significance test is

0.02 for Stopwatch test on right thumb, 0.01 for Stopwatch test on left thumb, 0.001 for Plate Tapping

and 0.008 for 5x5 Shuttle Run test. We can observe that all values are smaller than the significance

threshold at p< 0.05.

The rather small progress in speed from the initial to the final assessment is due to the specificity of

this motor quality. The results are not spectacular because of the increased heritability coefficient.

Discussions and conclusions

The physical education lessons would be preferable to be conducted using value groups with close

motor potential, which would lead to a positive correlation between pupils.

While recording the results, we found that differentiated instruction could be done based on the

ophthalmic deficiency, but it was not possible based on the associated disorders because of the large

number of different diagnostics existing in the classrooms of this study.

Using differentiated instruction in the physical education lesson at the secondary school level, we

have noticed an improvement of speed-related performances in visually impaired pupils. The initial

assessments applied to visually impaired pupils showed that some subjects were unable to perform the proposed tasks because of their associated disorders. Differentiated instruction involves the teacher’s

experience, meaning knowledge of the pupils’ motor, functional, somatic and psychological

particularities.

Instruction and education of visually impaired pupils requires the physical education teacher to have

extensive knowledge of physical education theory, didactics, methodology, physiology, psychology.

Acknowledgements

This paper is made and published under the aegis of the National University of Physical Education and Sports from Bucharest, as partner of a program co-funded by the European Social Fund within the Sectoral Operational Programme for Human Resources Development 2007-2013 through the project Pluri- and interdisciplinarity in doctoral and post-doctoral programmes, Project Code: POSDRU/159/1.5/S/141086, its main beneficiary being the Research Institute for Quality of Life, Romanian Academy.

References

Cârstea, Gh. (1993). Teoria și metodica educației fizice și sportului. București: Universul.

Lieberman, L., Ponchillia, P., & Ponchillia, S. (2013). Physical Education for Visual Impairments and Deafblindness: Foundation of Instruction.USA: AFB Press - American Fondation for the Blind.

Șerbănoiu, S., & Tudor, V. (2007). Teoria și metodica educației fizice și sportului. București: ANEFS.

Tomlinson, C. A. (1999). The Differentiated Classroom. Responding to the Needs of all Learners. USA: Association for Supervisor and Curriculum Development.

Winnick, J. (1985). The performance of visually impaired youngsters in physical education activities: Implication for mainstreaming. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 2(4), 292-299.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

10 June 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-010-5

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

11

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-509

Subjects

Sports, sport science, physical education

Cite this article as:

Marinescu, G., Cazan, C. I., Linca, N., Ianculescu, G., & Mujea, A. (2016). Study Regarding Speed Development in Visually Impaired Pupils Using Differentiated Instruction . In V. Grigore, M. Stanescu, & M. Paunescu (Eds.), Physical Education, Sport and Kinetotherapy - ICPESK 2015, vol 11. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 462-468). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.06.64