Study about the Perception and Practice of Nordic Walking as a Component of Active Tourism in Romania

Abstract

The paper addresses some general issues related to Nordic walking, a leisure sports activity with many positive influences on the body and mind, but unfortunately almost unknown in our country. The study has started from the hypothesis that if Nordic walking is systematically practiced, it will have multiple beneficial effects on the individual’s health and social relations. But to prove it, we need theoretical arguments and concrete evidence coming to support this assumption. To this purpose, we used bibliographical documentation and we conducted a research in Campina, between 8 and 29 December 2013, on a group affiliated to the Association for Health and Performance, made up of practitioners of weekend tourism in Breaza-Nistoresti region. The participants in Nordic walking, 21 subjects aged 22 to 64 years, responded to an 18-item questionnaire designed to identify, among others, their perception about the natural conditions and those created for the practice of leisure sports activities, the dimension and use of their free time, about Nordic walking in general, they also being asked to give their reasons for practicing this sport. The collected data were processed and interpreted, our findings underlying some relevant aspects related to Nordic walking, which might be both necessary and interesting, as we have to do with a sports discipline at its beginning in our country.

Keywords: Nordic walking, free time, leisure sports activities, benefits

Introduction

Nordic walking dates back from 1966, when a woman gymnastics teacher from Finland started

using “walking with ski poles” in her physical education classes with students. But only in 1997, she

presented her ideas publicly for the first time, they being noticed by the Finnish Central Association for

Recreational Sports and Outdoor Activities, which decided to experiment the activity in order to

promote it. This new sport was surprisingly quickly adopted by many countries (people associating

perhaps the Nordic lands with the concepts of fresh air, pure nature and healthy lifestyle), which

justified the foundation, in 2000, of the International Nordic Walking Association - INWA. If, in 2004,

3.5 million Nordic walkers were estimated in Europe, in 2013, their number increased to 10 million

practitioners (Oulton, 2014).

Nordic walking, a non-competitive physical activity suitable for all, regardless of age, gender or

physical condition, mainly aims at the general physical and mental wellbeing, its practice relying on

many principles among which we mention: safe, healthy, bio-mechanically correct movements and

gait; correct body alignment and posture; natural and fluid movements that engage the muscles of

upper and lower body, and also the heart; symmetrical and complete training of the whole body;

effective aerobic conditioning, by activating both large and small muscle groups that provide rhythmic

and dynamic movements; increased blood circulation and metabolism; continuous alternation of

muscle activation and relaxation, promoting relief in tight muscles; the intensity and training goals can

easily be adapted to individual needs; the learned skills can be transferred to everyday life (INWA,

2015). At the same time, Nordic walking improves the state of mind, relieves anxiety and depression,

provides mental balance, decreases apprehension, discharges muscular stress that may cause physical

injuries etc. It is recommended to people suffering from heart diseases, osteoporosis, diabetes,

hypertension, obesity etc. Moreover, in Nordic walking, fats are consumed first and carbohydrates only

after, unlike the other sports where consumption is in the reverse order (Duțu, 2014).

All these arguments explain the expansion of Nordic walking, which is approached by an

increasingly larger number of followers aware of its benefits on the body and mind, but also of the fact

that it is enjoyable and even socialising, if performed as a component of active tourism. Due to this

continuously upward trend, Nordic walking is nowadays deemed “to represent the sport with the

highest growth rate in Western Europe, being ‘in fashion’ equally among healthy and disabled people”

(Mersul nordic, 2012).

In Romania, Nordic walking has been “imported” in recent years, being still a “young” sport

discipline: few are those who know about it and even fewer those who practice it, some of them trying

to lose weight, others to heal their spine-related problems, while others perform it as a jogging

exercise. It seems that neither the category of practitioners nor that of non-practitioners has sufficient

information or is fully aware that “Nordic walking is 50% more efficient than simple walking, being

considered the second sport, after swimming, which exerts most of the muscle groups (more than

90%)” (Mersul nordic îi cucerește pe români, 2010).

Another important concept for our paper is that of “free time” or “leisure (time)”, which is so widely

spread nowadays that we shall not insist upon it, given the rich literature on this topic generated during

the last decades and largely focused on the formative-educational potential of this component -

sometimes a friend, other times an enemy of our daily life, depending on each individual’s ability to

take advantage of it or to waste it irreversibly.

“Rational use of free time has a tonic effect on both the human body and the personality

development, but most of all it contributes to maintain the individual’s physical freshness, a freshness

diminished by the informational and transformable life stress” (Balint, 2010: 10). And also the

individual’s mental freshness, we would add, because in the contemporary world the mental

component is more exerted than any other and more than ever, by virtue of the rather static work

activities, as part of the amazing technological progress.

Finally, the third concept used in this study is that of “leisure sports activities”, little researched in

Romania in the context of developmental psychology, but intensely explored in foreign literature,

particularly in the Anglo-Saxon one. Taking into account this imbalance, our paper tries to prove that

Nordic walking has multiple beneficial effects on its practitioners at the physiological, psychological

and social levels, which leads to an increase in their quality of life. This study aims to promote its

knowledge and recognition and implicitly to address psychologists the invitation of using leisure

activities in human development. All the more since modern society has been confronted for a while to

a constant, encouraging and probably one-way phenomenon, which is the growing interest of a large

mass of people in movement performing.

It is known that people who go to the gym, the stadium or do jogging are more emotionally stable,

more sociable and happier in their relations. This is actually the from which we have started

our research: Nordic walking is a physical activity that facilitates relaxation and good mood through

movement, promoting at the same time a lifestyle in harmony with nature.

The research states that if Nordic walking is systematically practiced, it will have

multiple beneficial effects on the individual’s health and social relations.

Materials and methods

Twenty-one subjects were included in the study, but the sample was not

considered representative, because the project allowed the presence of all those willing to perform a

given type of effort. Consequently, participants were aged between 22 and 64 years, most of them

being adult women (95.5%), graduates from higher education institutions (60%).

The research was conducted between 8 and 29 December 2013, in

Campina, on a group affiliated to the Association for Health and Performance, whose activities are

promoted on the internet and through the site Atlefitness (nature, health, beauty and physical vigour).

This association, directly interested in the employers’ professional performances, designed a very

flexible weekend programme called “A Healthy Weekend”. The group members, practitioners of

weekend tourism in Breaza-Nistoretiregion; were guided towardsan organiedphysical activity, a

sport easy to practice by any participant, namely Nordic walking.

Bibliographical documentation, an 18-item questionnaire (basically related to

Nordic walking, but also to other adjacent issues necessary for us to reach some findings and draw

some conclusions), statistical processing and interpretation, graphical representation.

Results

Among the 18 items of the questionnaire, we shall analyse only 8, thought to be the most relevant

for the topic addressed in this study.

Questions, responses and their interpretation

To, “Do you think that you have enough free time?”, 19 subjects respond in the affirmative and

2 in the negative (90.5% vs. 9.5%), which means that almost all of them admit that they have free time

available, obviously to a greater or lesser extent, but sufficiently. This indicates that the investigated

people have the opportunity to spend it in various ways, choosing the active or passive leisure activities

that fit best their need for physical and/or mental relaxation. Therefore most subjects, eager to break the

daily routine, try (and manage, in our case) to properly distribute the ordinary tasks so that they create a

balance between their free time and the work performed. The other 2, for whom the free time is not

enough, might have jobs requiring prolonged working hours, for instance, or might fail in well

organizing their daily schedule.

To,“Do you use to practice sports activities in your free time?”,20 subjects respond “yes” and 1

subject responds “no” (95.2% vs. 4.8%), which shows clearly that they prefer active leisure activities

(sports, in our case) in which they do get involved, as they have the habit to practice them, meaning

that their sports activity is consistent, not accidental. Sport, in general, is favoured by our respondents,

which might indicate that they are aware of its beneficial effects on the body and/or that they practice it

because it is entertaining, relaxing and has a socializing role, allowing communication and relations

with other participants. But whatever the reason may be, the most important thing is that the

interviewed subjects dedicate their free time to sports practice, which is encouraging for the promotion

of this activity field. The only subject who does not use to perform sports might be interested in other

types of leisure activities or might be one of those who has not enough free time to do sports

(according to).

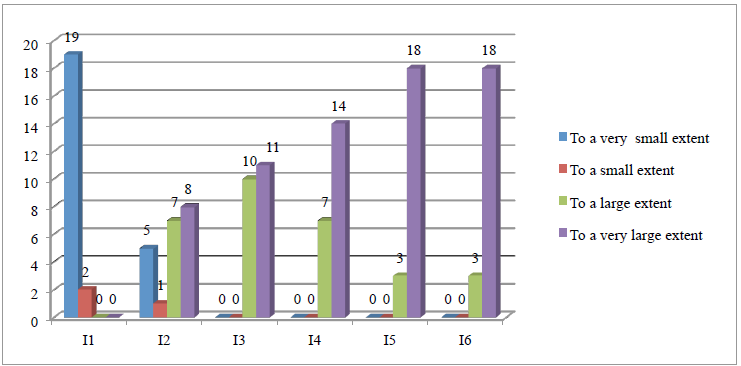

, “To what extent do you agree to the following statements?”, is made up of 6 items (I1-I6):

I1: “When I hear the word ‘sport’, I remain indifferent”; I2: “I like the competitive side of sports”;

I3: “The practice of Nordic walking gives me more energy”; I4: “The practice of Nordic walking gives

me pleasure”; I5: “The practice of Nordic walking is beneficial to physical health”; I6: “The practice of

Nordic walking is beneficial to mental health”. (Graph 1)

The collected data illustrate that the research subjects have recorded the highest scores to items 1, 5

and 6, which reveals the following aspects:

I1: the word “sport” arouses the respondents’ interest in movement performing (19 people), a characteristic of those individuals with an active lifestyle, who search for challenges and accept them,

unlike the 2 subjects who report that they remain somehow indifferent when hearing the word

aforesaid, maybe because the sports practice is not yet a habit for them or they are more sensitive to

words belonging to other spheres of life.

I5 and I6: for each item, an equal number of subjects (18) declare that the practice of Nordic walking is beneficial to both physical and mental health, an opinion highlighting their awareness of the

fact that human being, as a whole, can reach harmony only through the unity between body and mind;

moreover, the respondents seem to have found the sports activity able to achieve this goal, namely

Nordic walking. As to the remaining 3 people, who are not fully convinced of the assertions

aforementioned, they might be beginners in this activity, which would justify their reticence in giving

decisive “verdicts” before experiencing more deeply the positive effects of Nordic walking on their

own physical and mental health.

I2: in this case, responses are divergent, because the subjects have different opinions about the

competitive side of sports, namely 8 of them like this aspect to a very large extent, while 1 participant

is at the opposite pole, appreciating it to a very small extent, and the other 12 are in-between. We think

that this wide distribution of responses reflects each individual’s personality, according to which life is

regarded either as a competition inviting the protagonists to actively take part in or as a show inviting

the viewers to passively watch it.

I3: respondents agree to a very large extent (11) and to a large extent (10) that Nordic walking gives

them more energy, which can be explained by the fact that it engages most of the muscle groups,

toning them up, and this increases the practitioners’ vigour and fitness condition. But their energy level

also improves as a consequence of removing mental stress, whose accumulation and static presence

decrease the inner potential of the human body.

I4: responses indicate that the practice of Nordic walking is pleasant to a very large extent for one

third of the subjects (14) and to a large extent for 7 subjects. This means that the performed activity is

agreeable for all the investigated practitioners, a minor difference being given by the presence,

respectively the absence of the word “very”, which might actually be a way of perceiving the world

with more or less realism, enthusiasm or optimism.

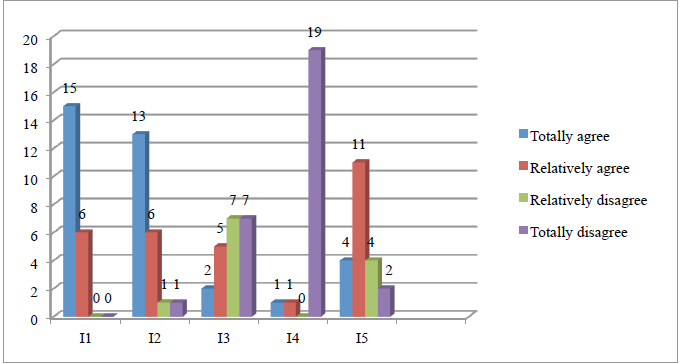

,“To what extent do you agree to the following statements about physical and sports activities?”,

includes 5 items (I1-I5):

I1: The region where I live offers me many opportunities to practice physical and sports activities;

I2: Local sports clubs and other centres in my region offer many opportunities for the practice of

physical and sports activities; I3: There are opportunities for the practice of physical and sports

activities in my region, but I have no time to benefit from them; I4: I am not interested in the practice

of physical and sports activities - I prefer doing something else in my free time; I5: Local authorities do

not do enough for the citizens in the field of physical and sports activities. (Graph 2)

The collected data illustrate the following aspects:

I1: most subjects (15) totally agree that the region where they live offers them opportunities to

practice physical and sports activities, while 6 relatively agree to this assertion, which means that there

exist natural conditions allowing people to exercise, but the decision to do it is a personal matter,

belonging to each individual.

I2: respondents have diverse opinions about the opportunities offered by local sports clubs and other

centres in the region to practice physical and sports activities. Thus, 13 totally agree to the expressed

idea, 5 are relatively content with the situation, 1 is not convinced that things are good enough and 1

definitely denies the existence of such opportunities. All these are difficult to interpret, because the

results might be influenced by the economic development in the area where they live, by the number of

inhabitants, their age and gender, their preference for the movement practice, but also, in our opinion,

by the “claims” or exigencies of each individual.

I3: the opportunities for practicing physical and sports activities in their region are valued by an

equal number of subjects, who respond that they totally disagree (7) and relatively disagree (7) to the

assertion that they would not have free time available to benefit from them. Consequently, this

category of people proves that “where there is a will, there is a way” and that man is the master of time,

and not conversely. Five subjects tend to accept that their free time is limited, which hinders them to

get involved in leisure activities, and 1 single declares that he/she has no free time. Overall, the

situation is promising, as one third of the subjects succeed in having a time of their own and using it for

their mental and physical relaxation.

I4: responses clearly demonstrate that most subjects (19) are interested in the practice of physical

and sports activities, instead of doing something else in their free time. However, 1 subject relatively

agrees to this statement, which might indicate a hesitation or a momentary indecision in responding

more accurately, and 1 subject totally agrees that he/she dedicates his/her free time to other kinds of

activities, obviously not related to movement performing. These 2 subjects, but especially the latter, are

the “exceptions that prove the rule”, in our case the preference for physical and sports activities, as a

source of wellbeing.

I5: subjects’ opinions about the fact that local authorities do not do enough for the citizens in the

field of physical and sports activities are again diversified, but, as we said before, this keeps to the

individual’s perception and exigencies related to the public services provided to a community and

implicitly to each of its members. So, according to 15 subjects (4 totally agree and 11 relatively agree),

more should be done in this regard, which might express a dissatisfaction with the current state of

things and a desire for better involvement of the local authorities in solving the issues related to the

practice of physical and sports activities. Their requests might be about facilities, equipment,

schedules, management or many others. However, 6 subjects are more tolerant, as 4 relatively disagree

and 2 totally disagree with the statement above-said, which might mean that they are almost,

respectively fully content with what the decision-makers do at the local level. This is a good

perspective and indicates a possible upward trend in people’s perception about the satisfaction of their

needs, which are not ignored any longer, but taken into consideration and fulfilled.

To,“How did you find about Nordic walking?”,16 subjects (76.2%) mention their friends, 2

(9.5%) indicate Google, 2 (9.5%) report other sources and 1 (4.8%) says that as a response to an

invitation. The obtained percentages lead to the conclusion that friends have a major role in influencing

their group to practice Nordic walking, as an alternative to a sedentary lifestyle, in the case of non-

athletes, or as a challenge to attempt something new, in the case of those who already practice one or

many sports. This method seems to work best, because friends have the greatest power of persuasion,

they are trusted and sometimes are examples to follow.

To, “Do you use to practice Nordic walking in your free time?”, 20 subjects respond in the

affirmative and 1 subject in the negative (95.2% vs. 4.8%). The high percentage of practitioners can be

explained by the fact that they act in a team spirit, within a group formed a few months before

participating in the investigation. Therefore, it seems normal for them to spend their free time together,

joined by a common passion called Nordic walking. The subject whose response is “no” is a retired

woman at her first contact with this sport, but she does not exclude the possibility to perform it in the

future.

To,“If you respond ‘yes’, give the main reason for which you use to practice Nordic walking”,

out of the remaining 20 subjects (1 said “no”, according to), 9 (45%) declare that for socialization,

5 (25%) for keeping their physical fitness, 3 (15%) for improving their health state and 3 (15%) for

meeting their friends. This statistic is somehow contrary to expectations, because we thought that the

health-related reasons would be on the first place. Instead, the participants’ need for socializing is

stronger than any other reason, reaching almost half of their options. It is true that socialization

contributes to identity building, social self-assertion, creation of (sometimes) long-lasting relations etc.,

but besides these benefits, modern man seems to feel a strong desire to be with humans in a world of

machineries and devices, in an alienating virtual universe. Maintaining their physical fitness is also

important to our subjects, who certainly know that the complete movements of Nordic walking tone up

all the body muscles and allow the full strengthening of muscle and joint chains. Besides, the weight

loss comes as a consequence of high energy expenditure: the Nordic walker consumes around 400

calories per hour compared to the 280 calories consumed during traditional walking (Duțu, 2014). And,

finally, the subjects’ interest in their health state registers the same percentage as meeting their friends

for practicing Nordic walking. This seems somehow bizarre to us, because to practice a sport just to

meet one’s friends is not a serious approach to movement performing. Logically, the health-related

reasons should have enjoyed a better position, since Nordic walking is known to improve body

functions, for example, breathing: the body posture allows a full opening of the thoracic cage ensuring

greater pulmonary amplitude, therefore extra oxygenation and better irrigation, consequently an

increase in both cardiovascular capacity and heart rate.

For, “How often do you use to practice Nordic walking?”, responses given by the 20 subjects

(1 does not practice this sport, see) are unevenly distributed, as follows: every day - 4 (20%), 3 to 5

times per week - 8 (40%), once or twice per week - 4 (20%), once or twice per month - 3 (15%), very

rarely - 1 (5%). These statistical data show that only 4 people perform Nordic walking every day,

therefore on a regular basis, which proves that they have acquired this habit, probably because they

appreciate and are confident in its effects on multiple levels. Such a result confirms that people need to

do something different from their usual work, so that they escape from banality and “recharge their

batteries” for a new day. Unfortunately, the number of those who pay attention to the necessities of

their own body, who carefully listen to it and try to fulfil its silent claims is still low; but “there is a

beginning to everything”, therefore a hope that things might change for the better in the case of Nordic

walking too, with the full understanding of its benefits and with the help of a more “aggressive”

popularization, if required by the poor health status of a category of people or even of a whole nation

(it is not an exaggeration, because sedentariness tends to affect people from the most tender to the

oldest age). Eight of the investigated subjects practice this sport 3 to 5 times per week, which is not bad

at all and demonstrates that they treat Nordic walking seriously and rigorously, while enjoying its

benefits as often as possible. Four people get involved in this activity once or twice per week, which is

still good and shows that they are willing to continue performing this activity according to their

schedule. The 3 participants in Nordic walking with a frequency of once or twice per month can be

considered occasional practitioners, able to leave it and return to it anytime, maybe on the basis of

some momentary moods or influences. For 1 subject, Nordic walking is a sporadic activity, which

might indicate that he/she is not fond of it and remembers it when other variants are not available for

various reasons.

Discussions and conclusions

Through this study, we wanted to identify the perceptions and experiences of the investigated

sample regarding the conditions available to them for the practice of leisure sports activities, the

dimension and use of their free time, their involvement in movement performing - with special

emphasis on Nordic walking, their reasons for practicing this sport, and many others. The aim was to

see whether this new and almost unknown activity in our country would be able to capture in the future

the attention and interest of an increasingly number of people, so that it becomes as popular as in many

Western countries, where lots of practitioners fully enjoy it.

The activity proposed in our research took into account that our modern technological society

allows people much more free time to be used on each one’s choice, but they must be provided

alternatives and must be permanently stimulated to cope with new challenges, in our case Nordic

walking, as a component of active tourism or a leisure sports experience able to bring a “fresh breath”

and a “welcome break” in the daily routine.

The fact that preponderantly the graduate adult women (95.5%) enrolled in our project is somehow

surprising, because usually they are busier than men, having not only professional, but also everlasting

domestic tasks. However, they were able to “reconcile” between their inner need for a personal life and

the external constraints, and to “find” the free time for taking part in the research. They also have

enough free time available, as shown by the questionnaire, to practice Nordic walking either to

socialise or to be in shape, or to be healthier, or maybe all of them. Their higher instruction level might

have had an important contribution to opening new perspectives on approaching and better managing

the life issues.

Synthesising and regrouping the collected responses, we can draw some conclusions based on the

“peak” trends revealed by the study: subjects have enough free time available during which they

practice active leisure activities, sports (in our case), and particularly Nordic walking, on a relatively

regular basis (3 to 5 times per week); they do it for socialization, while being aware of its beneficial

effects on the physical and mental health; they found about it mainly from their friends; they are

content with the opportunities for the practice of physical and sports activities existing in their region.

The obtained results seem to be encouraging for a leisure sports activity at its beginning in our

country, but, in our opinion, an increased popularization of this sport, through media and within

educational and professional environments, would be possible to bring throughout the years more and

more followers willing to really practice or at least to try this sport and feel “live” its impact on their

existence.

To conclude, the research hypothesis, stating that “if Nordic walking is systematically practiced, it

will have multiple beneficial effects on the individual’s health and social relations”, has been validated

by the theoretical arguments and the data provided by the investigated subjects.

References

Atlefitness (nature, health, beauty and physical vigour). (2015). Retrieved from http://nicu-

pvl.wix.com/atlefitness

Balint, Gh. (2007). Activități sportiv-recreative și de timp liber: paintball, mountain bike și escaladă. Iași:

PIM.

Duțu, O. (2014). Nordic walking: sport plăcut, relaxant, eficient. Retrieved fromhttps://www.slabsaugras.ro/

nordic-walking-sport-placut-relaxant-eficient-art-4728.html

INWA. (2015). What is Nordic walking. Retrieved from http://inwa-nordicwalking.com/about-us/what-is-

nordic-walking/

Mersul nordic - Un sport la modă pentru întreținerea sănătății. (2012). Retrieved from

http://stiri.tvr.ro/mersul-nordic-un-sport-la-moda-pentru-intretinerea-sanatatii_18720.html

Mersul nordic îi cucerește pe români. (2010). Retrieved from http://www.gandul.info/magazin/mersul-nordic-

ii-cucereste-si-pe-romani-arde-caloriile-si-poate-fi-practicat-pe-orice-vreme-6189872

Oulton, R. (2014). A brief history of Nordic walking. Retrieved from http://www.nordicwalkingfan.com/a-

brief-history-of-nordic-walking/

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

10 June 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-010-5

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

11

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-509

Subjects

Sports, sport science, physical education

Cite this article as:

Ivan, ., & Popescu, L. (2016). Study about the Perception and Practice of Nordic Walking as a Component of Active Tourism in Romania. In V. Grigore, M. Stanescu, & M. Paunescu (Eds.), Physical Education, Sport and Kinetotherapy - ICPESK 2015, vol 11. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 13-21). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.06.3