Abstract

Considering the fact that the use of short measurement instruments is much more practical and cheaper, it is of utmost importance to create and validate them. Besides, within the limited time, researchers may need to apply a very brief measure. One of them is the very brief measure of the Big-Five personality dimensions, called Ten Item Personality Inventory. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the construct validity and reliability of the Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) applied on a Croatian adult sample. After the translation of the original TIPI, it was applied on a sample of 432 adults who voluntarily participated in the research. The exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses with Principal Axis Factoring and Oblimin rotation were run with the reliability level analysis. The exploratory FA demonstrated the four-factor solution, which has explained 66.54% of the total variance. The confirmatory FA showed that the five-factor-solution explained 74.38% of the total variance. However, the determined factor structure was not clear and the proposed theoretical model of the Big Five was only partially confirmed. Cronbach alpha coefficient was =.66. Since the major loadings in the first factor were mainly situated on positively oriented items, this research confirmed prior findings about negatively oriented items as strong obstacles in the analysed factor structures. Therefore, the main conclusion of this research is to adapt TIPI in the way to create all ten items as positively oriented.

Keywords: Ten Item Personality Inventoryadultsvalidation

1. Introduction

Methodological attempts to achieve the criterion of economy in creating and applying measures

such as self-questionnaires has had a long history (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2007). One of these

attempts is related to the need of shortening the administration time when exploring focus variables in a

particular research. This need has arisen from the fact that sometimes researchers do not have enough

time, or from the fact that participants do not have or do not want to or cannot spend a long time on

filling in a certain questionnaire. Therefore, all these reasons support the continued effort to create

economically and psychometrically adequate measures, especially in the field of personality

psychology (Rammstedt & John, 2007). However, even if it was more than practical to ask just one

question about individual personality, multiple-item scales showed a very dominant psychometrically

superiority in relation to brief measures. Still, some of them such as Ten-Item Personality Inventory

(Gosling, Rentfrow & Swann, 2003) have demonstrated satisfactory validity and reliability. This was

intriguing enough to check TIPI’s psychometric properties on an adult sample in Croatia.

1.1.Big-Five personality dimensions and their measurement

The Big-Five personality theoretical model has been the most empirically validated and the most

used personality framework worldwide (Tatalović Vorkapić, 2014). It has presented one of the most

significant personality theories in the 20th century (Mlačić, 2002). Its influence has been enormous

since it presented the best answer on scientific discourse about the number of personality dimensions.

On the other hand, although there are some arguments against its privileged status in personality

psychology (Block, 1995; Tatalović Vorkapić, 2014), this theoretical model has been able to found the

simplest way to be operationalized and measured. It presents the hierarchical model of personality

traits that are included as the best descriptors of five much broader dimensions or domains:

extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness to experience. This

theoretical framework is mostly descriptive with emphasized internal taxonomy (MacDonald, Bore, &

Munro, 2008). These descriptors are adequately reflected through the language and behaviour, so

1993, p. 91) and

p.75). An extraverted person could be described as talkative, active, assertive, energetic, enthusiastic

outgoing, warm, expressive, sociable, gregarious with positive emotionality. An individual with a high

agreeableness is described as kind, trusting, sympathetic, generous, appreciative, forgiving, non-

critical, compassionate and altruistic. A highly conscientiousness person is responsible, organized,

planful, reliable, responsible, thorough, productive, ethical, self-disciplined and competent. A highly

neurotic individual is anxious, tense, touchy, unstable, self-pitying, worrying, hostile, vulnerable and

moody. A person with high openness to experience is imaginative, original curious, artistic, insightful,

introspective and aesthetically reactive (John & Srivastava, 1999; McCrae & John, 1991).

With the aim of measuring the Big-Five dimensions, several measures have been developed. Costa

and McCrae (1992) have created the NEO Personality Inventory and its revised version (NEO-PI-R),

which has 240 items. It is very detailed since it measures the big five dimensions and their specific

facets. It takes about 45 minutes to fill in this self-questionnaire due to its length. Later on, the same

authors created a shorter measure, the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI), which consists of 60

items. Furthermore, the Big-Five Inventory has been developed so that it contains 44 items (Benet-

Martinez & John, 1998; John & Srivastava, 1999). Goldberg (1992) has developed a 100-item

personality measure named Trait Descriptive Adjectives (TDA) that was shortened later on by Saucier

(1994) from a 100- to a 40-item questionnaire. NEO-PI and BFI are adapted and validated in Croatia

(http://www.nakladaslap.com/testovi.aspx?cat=mguid_KPUpitniciIPostupciZaIspit). However, all of

these masures take time to be applied, which implies at the need for developing a shorter one.

1.2.Ten-Item Personality Inventory – TIPI

Having the possibility to measure psychological constructs with short instruments presents the

advantage not only for researchers who have a limited assessment time, but also for these one who

need to confirm or disconfirm theoretical models (Cloninger, 2009). Therefore, the benefits from

designing short measures are multiple, and these brief instruments could be applied in longitudinal

studies, large-scale surveys, clinical research, pre-screening packets and experience-sampling studies

(Robins, Hendin & Trzesniewski, 2001).

Due to the psychometrical superiority of multi-item scales, one must think that there is no big

number of short measures in psychology. However, this is not the case. Burisch (1997) has

demonstrated that the brief depression scale had satisfactory psychometric properties, same as the long

scales. Another example of a valid and reliable short scale is related to the field of self-esteem and it

was developed by Robins and colleagues (2001). Within the field of personality psychology, three brief

instruments have been developed: Big-Five Inventory-10 (Rammstedt & John, 2007); Ten-Item

Personality Inventory & Five-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI & FIPI; Gosling, Rentfrow & Swann,

2003).

In the first case, Rammstedt and John (2007) selected two basic items for each personality

dimension based on consensual expert judgment and the empirical item analyses for getting the

descriptors of the core traits. So, they have selected two BFI-items for each personality domain parallel

in two languages: English and German. In that procedure, they followed criteria such as choosing items

that represented: the high and low poles of each factor; core aspects but not redundant of each domain;

identical language versions; items that showed the highest correlations with the original BFI-scale; and

items that related only to one expected factor, and not other four factors (Rammstedt & John, 2007).

Discriminant and convergent validity and test-retest reliability were run on two students’ samples in

two time measurements: American sample (N1=726 and N2=726) and German sample (N1=457 and N2=376). Rammstedt and John (2007) determined that BFI-10 had satisfactory psychometric properties. However, they emphasized the psychometrical limitations of BFI-10, so it could only be

used as an additional measure of personality and not as substitute for standard personality measures.

Furthermore, Gosling and colleagues (2003) on the sample of N=1704 and N=1813 students, with

different sample groups in two time measurements, investigated the psychometric properties of the

Five- and Ten-Item Personality Inventories. Both FIPI and TIPI were examined by running convergent

and discriminant validity, and test-rest reliability. Unlike the selection criteria used by Rammstedt and

John (2007), Gosling and colleagues (2003) used the criteria based on optimizing the content validity

of FIPI and TIPI. Based on the suggestions of Goldberg (1992), Hazan and Shaver (1987) and John and

Srivastava (1999) selected core items using the following directions: striving for breadth of coverage;

identifying items that represented both poles of each domain; choosing those items that were not

evaluative extreme; avoiding those items that were simple negations; and avoiding redundancy in

selected items. Determined psychometric properties of FIPI were less satisfying than the psychometric

properties of TIPI. Besides, single-item scales are not able to control the acquiescence bias or to permit

the researcher to check for errors. Therefore, in that case, as the brief scale of two items per personality

domain, TIPI presented a better solution for measuring personality in a limited assessment time. Even

though the limitations of short personality scales are obvious, the main contributions of using TIPI in

personality research are: a) it is the best solution in studies where brevity is a very high priority

(Saucier, 1994); b) its use provides an accumulation of research findings (Gosling, Rentfrow & Swann,

2003); and c) its item non-redundancy reduces the subjects’ boredom, frustration and demotivation of

participating in personality studies (Burisch, 1984).

2.Research aim, problems and hypothesis

The main aim of this study was to adapt and validate the Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI;

Gosling, Rentfrow & Swann, 2003) on a Croatian adult sample. Regarding this aim, the following

research problems related to TIPI were explored: a) its validity using the factor analysis; b) its

reliability in calculating Cronbach alpha; and c) its descriptive parameters on an adult sample. It was

expected to determine five-factor structure with a lower level of reliability since a very brief measure is

applied. In addition, similar descriptive parameters as in prior studies have been expected to be

determined.

3.Method

3.1.Subjects

In this pilot study, a total sample of N=432 teachers (4 males) self-estimated their personality on

TIPI. This sample consisted of three subsamples (N=220; N=202; N=10) from the studies that were run

for the purposes of three students’ master theses. All teachers within these three subsamples

participated at the same time from randomly chosen 24 kindergartens and 11 primary schools in

Croatia (N=117 primary school teachers and N=315 preschool teachers). Since these subsamples were

similar regarding all relevant variables (such as age, working experience, participation time, culture,

(pre)school curricula), the following analyses were run on the total sample. The average age is

M=39.11 years (SD=10.41) and it ranged from 22 to 64 years. The average working experience is

M=16.12 years (SD=11.36), which ranged from 0 to 43 years. Teachers are working in these cities:

Crikvenica (N=17), Grobnik (N=10), Kastav (N=52), Krk (N=23), Matulji (N=33), Opatija (N=56),

Rab (N=24), Rijeka (N=195), Tribalj (N=6) and Viškovo (N=16).

3.2.Measure

The Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI; Gosling, Rentfrow & Swann, 2003) was applied in this

study. Due to its adaptation into Croatian language, back-translation was done in cooperation with

psychologists and experts of Croatian and English languages. The Croatian version of TIPI, the

instruction for using and scoring, can be seen in Appendix A. It consists of ten items that measure five

personality dimensions: Extraversion (E), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness (C), Emotional

Stability (ES) and Openness to Experience (O). Each dimension is measured by two descriptors, one of

each pair is reverse-scored, as it is observable in Table 1. The common stem was used:

reliability levels are previously determined as Cronbach alphas: E=.68; A=.40; C=.50; ES=.73 and

O=.45 (Gosling, Rentfrow & Swann, 2003).

3.3.Procedure

This research presents a set of three independent but coordinated studies within three students’

master theses. All of them were run at the same time (between February and June 2015) in 24

kindergartens and 11 primary schools in Croatia. The Faculty of Teacher Education approved data

collecting in collaboration with participating kindergartens and primary schools. All kindergarten and

primary school principals agreed to participate in this study. Data anonymity and confidentiality were

guaranteed, and teachers participated voluntarily. It took about one minute to complete TIPI.

4.Results and discussion

4.1.Content validity

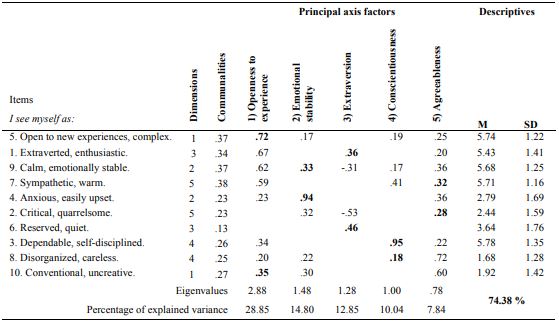

To explore the validity of the applied TIPI on the Croatian adult sample, two factor analyses were

run and the final structure matrix of principal axis factors with Oblimin rotation, communalities and

descriptives for each item are presented in the Table 1.

Before running the factor analysis, the negatively oriented items (2, 4, 6, 8, 10) were reversely

scored. In the first step, the exploratory factor analyses with Principal Axis Factoring and Oblimin

rotation with Kaiser Normalization was run. It was decided that this type of factor analyses would be

applied since correlations between factors were expected. In addition, it was decided to present a

structure and not a pattern matrix, because a pattern matrix is less stable from sample to sample and it

requires a well-designed study with a sufficient sample size. This study is the first validation study of

TIPI in Croatia, and its sample is relatively big. So, it may be considered a pilot study. Therefore, a

structure matrix presents a better solution for this study and it shows zero-order correlations between

factors and variables, and not regression coefficients (Kline, 2000; Sapp, 2006). The exploratory FA

resulted with the four-factor solution, which has explained 66.54% of the total variance. Its structure

matrix has shown highest loadings of all positively oriented items (1, 3, 5, 7, 9) on the first factor.

Other three factors had loadings of separate negatively oriented factors (second factor: items 2 & 4;

third factor: item 6; and forth factor: items 8 & 10).

However, due to the Big-five theoretical model that was in the background of this brief measure,

the confirmatory factor analyses with Principal Axis Factoring and Oblimin rotation with Kaiser

Normalization was run. Within this second step, it was specified to extract five factors. The determined

five-factor solution has explained 74.38% of the total variance. Overall results of the confirmatory

factor analyses can be observed in Table 1. Very similar to what was determined in exploratory factor

analyses, the highest loadings were on the first factor. Items that were gathered around this factor are

again positively oriented items. As ti can be observed, generally items’ communalities and loadings are

not so high, and they are not structured as it was expected. On the other hand, even though the

determined structure is not so clear, the bolded loadings showed that the expected five-factor groupings

could be recognized at the latent level. Based on these bolded loadings, even though some of them are

very low and with caution, the big-five structure could be defined. However, this was also expected

based on Gosling and colleagues’ observations (2003), since they warned about the questionable

validity of this brief measure as explored by factor analysis. Therefore, the main conclusion regarding

the first problem of this study was that the determined factor structure was not clear and the proposed

theoretical model of the Big Five was only partially confirmed. Since the major loadings in the first

factor were mainly situated on positively oriented items, this research confirmed prior findings about

negatively oriented items as strong obstacles in the analysed factor structures. Therefore, the main

conclusion of this research is to adapt TIPI in such a way so as to create all ten items as positively

oriented. Besides this conclusion, additional guidelines for future research should be related with the

same guideline stated from Gosling and colleagues (2003), the one within which the discriminant and

convergent validity should be run, due to inferior content validity and internal consistency reliability of

brief personality measures.

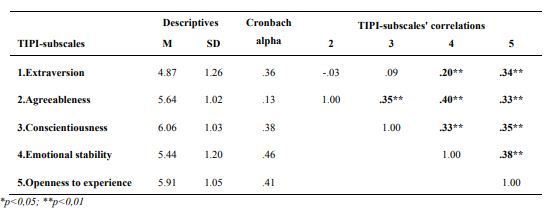

4.2.Internal consistency reliability

With the aim of analysing the internal consistency reliability, Cronbach alphas for all five TIPI-

subscales and for the overall inventory were calculated. Negatively oriented items were also reversely

scored. As it was expected, low reliability levels were determined for each TIPI-subscale, as it can be

seen in Table 2. Especially low reliability was found for the Agreeableness subscale, which is

interesting. This finding could be explained by the possibility of poor translation, which should be

taken into account in future research. The overall internal consistency reliability level calculated as

Cronbach alpha coefficient was =.66, which was relatively satisfying. In comparison to previously

presented Cronbach alphas of the original TIPI (Gosling, Rentfrow & Swann, 2003), it can be observed

that the reliability levels in this research are lower in relation to the original ones. The greatest

difference is between reliabilities of Agreeableness, and the greatest similarity is between reliabilities

of Openness to experience. This again implies at the fact that the adaptation of the two Agreeableness

items should be revised. Besides this implication, the other one derived from Gosling and colleagues

(2003) should be taken into account too. Due to a small number of items it is logical to expect low

levels of internal consistency reliability to be determined in a validation study. Therefore, they propose

to run a test-retest reliability check, which should be done in the future validation research of TIPI in

Croatia.

4.3.Descriptive parameters of the Big-five dimensions measured by TIPI

With the aim of answering the third study problem, basic descriptive and correlation research was

run. Therefore, besides reliability levels, Table 2 also demonstrates the results from descriptive

analyses of the applied TIPI. It can be seen that the determined means and standard deviations are

similar to those determined in the original research (Gosling, Rentfrow & Swann, 2003). Based on the

theoretical model of the Big-Five (John & Srivastava, 1999; McCrae & Costa, 1990, 2011), it was

expected to determine high and statistically significant correlations between all five-personality

dimensions. However, in this study, extraversion and agreeableness showed very small and statistically

non-significant intercorrelations (Table 2). Different subscale intercorrelations imply a different

structure of both: specific personality dimensions and the whole measure that tends to measure all

personality domains. This finding again implies at the fact that both the validity and reliability of TIPI

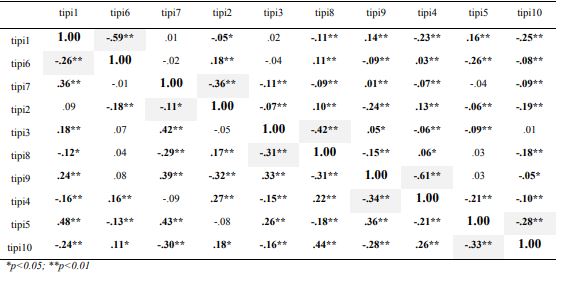

used in this study could be improved. Furthermore, detailed intercorrelations between all TIPI-items

could be thoroughly observed in Table 3, especially those between two items that belong to a certain

personality dimension. Under the diagonal, the intercorrelations of TIPI-items from this research were

presented, and above the diagonal the intercorrelations of TIPI-items from original research (Gosling,

Rentfrow & Swenn, 2003) were presented. Intercorrelations between the items of the same personality

dimension are shown in the grey cells. So, comparing these correlation coefficients, it is noticeable that

they are all negative and statistically significant, which was expected. However, most of them are much

bigger in the findings determined in the study of Gosling and colleagues (2003) than in the results

found in this research. This comparison could be concluded with the statement that future research is

definitely needed with specific modifications that should be implemented in the study design.

5.Conclusion

Even though this is a very well known fact, this study has confirmed that the brief personality measure

has some serious limitations. Firstly, both factor analyses failed to determine the expected Big-Five

structure of the Ten-Item Personality Inventory. Put very cautiously, that Big-Five theoretical model

operationalized and measured by TIPI on Croatian adult sample was only partially confirmed. Even

though two items of each personality dimension could be recognized within the same factor, the greater

loadings are at the first factor and they are situated on the most positively oriented items. Similar to this

finding is the next one related to the second research problem – TIPI-reliability. Even though, there

was no expectation of determining high levels of internal consistency reliabilities, those determined in

this study are significantly low, especially the one related to the dimension agreeableness. Again, the

determined descriptive parameters demonstrated different relationship of extraversion and

agreeableness with other personality dimensions. In addition, the lowest negative correlation between

two descriptors is the one determined at agreeableness dimension. Therefore, several limitations should

be taken into account when designing a future validation study of TIPI in Croatia.

Firstly, it was clearly demonstrated that the idea about having two descriptors for each personality

dimensions, of which one is negatively oriented, is not sustainable in the psychometrically point of

view. Therefore, the TIPI-adaptation should be done with all items positively oriented.

Secondly, maybe there are flaws in translation that was done, so maybe the right approach to

searching two main descriptors of five personality dimensions should be more empirically based and

not only translation-based.

Thirdly, as Gosling and colleagues (2003) have proposed, psychometric properties of the brief

personality measures should be tested using measures of convergent and discriminant validity and

measures of test-retest reliability instead of using measures in this particular study.

Forthly, this study was run on a sample of adults but all teachers, mostly women. Therefore, a much

more heterogeneous sample by variables should be used such as gender, age, education level and

vocation.

Fifthly, even though this was a pilot study that used a relatively small sample of 432 teachers, in the

future validation study, a bigger sample than this one should be used.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Samuel D. Gosling for giving the approval of adapting and applying TIPI on a Croatian sample.

References

- Benet-Martínez, V.John, O. (1998). Los Cinco Grandes across cultures and ethnic groups: Multitrait-multimethod analyses of the Big Five in Spanish and English. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 729-750

- Block, J. (1995). A contrarian view of the five-factor approach to personality description. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 187-215

- Burisch, M. (1984). Approaches to personality inventory comparison of merits. American Psychologist, 39, 214-227, construction. A

- Burisch, M. (1997). Test length and validity revisited. Cloninger, Conceptual issues in personality psychology. In: P. J. Corr & G. Matthews (Eds.) The Cambridge Handbook of Personality Psychology (pp. 3-26). The Cambridge University Press, USA. Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K. (2007). Metode istraživanja u obrazovanju (The research methods in education. In Croatian).. European Journal of Personality. Naklada Slap: Jastrebarsko. , 11, 303-315, S. (2009)

- Costa, P. T.McCrae, R. R. (1992). NEO-PI-R Professional, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. , manual. Odessa

- Goldberg, L. R. (1992). The development of markers for the Big Five factor structure. Psychological Assessment, 4, 26-42

- Gosling, S. D.Rentfrow, P. J.Swann, W. B. Jr. (2003). A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 504-528

- Hazan, C.Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524

- Kardum, I.Smojver, I. (1993). Peterofaktorski model stukture ličnosti: Izbor deskriptora u hrvatskom jeziku [Big Five model of personality: Selection of descriptors in Croa-tian Croatian]. Godišnjak Zavoda za psihologiju Rijeka, 2, 91-100, language. In

- Kline, P. (2000). Handbook of psychological testing (2nd ed.). & Francis Group. , Routledge. Taylor

- Sapp, M. (2006). Basic Psychological measurement, research designs, and statistics without math. Charles C Thomas, Publisher. Ltd

- John, O. P.Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical L. A. Pervin, & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research. , 102-138, perspectives. In

- MacDonald, C.Bore, M.Munro, D. (2008). Values in action scale and the Big 5: An empirical indication of structure. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 787-799

- McCrae, R. R.Costa, P. T. Jr. (1990). Personality in adulthood. TheGuilford Press

- McCrae, R. R.Costa, P. T. Jr. (2011). The Fife-Factor theory of L. A. Pervin, R. W. Robins & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed. , 159-181, personality. In

- McCrae, R. R.John, O. P. (1991). An introduction to the Five-Factor model and its applications. Personality: Critical Concepts in Psychology, 60, 175-215

- Mlačić, B. (2002). Leksički pristup u psihologiji ličnosti: Pregled taksonomija opisivača osobina ličnosti [The lexical approach in personality psychology: A review of personality descriptive Croatian]. Društvena istraživanja, 4-5 , 553-576, 60-61, taxonomies. In

- Rammstedt, B.John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. Journal of Reaserch in Personality, 41, 203-212

- Robins, R. W.Hendin, H. M.Trzesniewski, K. H. (2001). Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 151-161

- Saucier, G. (1994). Mini-markers: A brief version of Goldberg’s unipolar Big-Five markers. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63, 506-516

- Tatalović Vorkapić, S. (2014). Je li privilegirani status modela osobina ličnosti u psihologiji ličnosti opravdan? – Prikaz modela identiteta (Is privileged status of personality traits’ models in personality psychology justified? –Description of identity Croatian). Suvremena psihologija, 17(2), 181-198, models. In

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

14 May 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-007-5

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

8

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-252

Subjects

Psychology, social psychology, group psychology, collective psychology, teaching, teaching skills, teaching techniques

Cite this article as:

Tatalović Vorkapić, S. (2016). Ten Item Personality Inventory: A Validation Study on a Croatian Adult Sample. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences - icCSBs 2016, May, vol 8. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 192-202). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.05.20