Abstract

Resilience is understood as capability to recover from adverse events. However, it is not clear how resilience relates with anxiety, depression and energy in socially diverse European countries. Research question. How resilience relates with anxiety, depression, energy levels in European citizens? The purpose of study is to assess links between psychological resilience and anxiety, depression and energy in Western Europe, Scandinavia and Baltic States. Research methods. Experts-generated single-item questions from European Social Survey round 6 were used to assess psychological resilience, anxiety, depression, and energy levels. Countries were grouped according to the United Nations classification. Linear regression analysis was used to assess relationship between the psychological constructs. Findings. In Western Europe and Scandinavia higher levels of psychological resilience are predicted by lower levels of depression and anxiety, higher levels of energy, as well as male gender and younger age (in Western Europe) (all p<.042). In Baltic States higher levels of psychological resilience are predicted by lower levels of depression and higher levels of energy (all p<.023). Conclusions. Psychological resilience in most European countries is predicted by lower levels of depression and anxiety and higher levels of energy. More detailed research is needed to discover country differences in psychological resilience and its correlates.

Keywords: ResilienceanxietydepressionenergyEuropean countries

Introduction

Humans in their life usually encounter varieties of stressors, which range from simple everyday

challenges to major life decisions. It is common to think that greater amount of stress contributes to

worse physical and mental health (Jarašiūnaitė, Kavaliauskaitė-Keserauskienė, Perminas, 2012), and

scientists try to find answers why some individuals become overwhelmed with common everyday

challenges while others produce neutral or even positive reactions (and consequences) to most everyday challenges (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Bonnano, 2004). One of possible psychological

characteristic which may be able to explain why some individuals are able to stand, or even thrive in

the pressure of their everyday lives is psychological resilience (Fletcher & Sarkar, 2013). Psychological

resilience can be defined as “An individual’s stability or quick recovery (or even growth) under

significant adverse conditions” (Leipod & Greve, 2009, p. 41).

Higher psychological resilience relates with lower risk of various physical and mental disorders (e.g.

Davydov, Stewart, Ritchie, Chaudieu, 2010). Also higher psychological resilience relates with greater

amount of positive emotions which in turn also relates with better physical and mental health (e.g.

Tugade, Fredrickson, Barrett, 2004). So it may be assumed that psychological resilience can be

beneficial both for physical and mental health. However, a question how psychological resilience

relates with other psychological or social variables is not fully answered.

Studies show that women tend to lower psychological resilience than men (Bonnano, Galea,

Bucciarelli & Vlahov, 2007), but other studies did not find differences between gender and

psychological resilience (Pietrzak & Southwick, 2011). Older age also relates with higher

psychological resilience (Bonnano, Galea, Bucciarelli & Vlahov, 2007; Pietrzak & Cook, 2013).

Results with levels of education suggest that higher levels of education does not relate with higher

levels of psychological resilience (Bonnano, Galea, Bucciarelli & Vlahov, 2007), but other studies

show otherwise (Bonanno, Galea, Bucciarelli & Vlahov, 2006; Pietrzak & Southwick, 2011; Pietrzak &

Cook, 2013). Lower levels of psychological resilience are related with loss of income, lower perceived

social support and lower income (Bonanno, Galea, Bucciarelli & Vlahov, 2007; Pietrzak & Cook,

2013). Also respondents with lower psychological resilience more likely live alone, without a partner

(Pietrzak & Southwick, 2011; Pietrzak & Cook, 2013). Studies also demonstrate that higher

psychological resilience relates with higher extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional

stability and lower openness to experiences (Pietrzak & Cook, 2013), also with higher altruism,

religiosity and active lifestyle (Pietrzak & Cook, 2013). Psychologically resilient individuals tend to

show lower amount of depressive symptoms (Pietrzak, Johnson, Goldstein, Malley & Southwick, 2009;

Gooding, Hurst, Johson & Tarrier, 2012), they are more often optimistic, energetic, open to experience,

have high positive affectivity (Klohnen, 1996). M. M. Tugade and B. L. Fredrickson (2004) argue that

positive emotions are important for psychological resilience. So one may assume that psychological

resilience relates with some psychological constructs as well as with socio-demographic variables, but

these relationships are not unambiguous.

There is a possibility that psychological resilience depends on cultural and geographic differences.

R. Hassink (2009) argues that resilience can explain why some regions renew themselves and why

others declines in the face of the same adversities. There are also publications where resilience is

investigated in different enterprises (Sheffi, 2005) and different cities (Vale & Campanella, 2005), but

these studies were focused on economics, politics, but not psychology. Also there is a possibility that

psychological resilience have different predictors in different regions or countries in the same way as in

different cities or organizations.

Also there are some studies which show that positive emotions, psychological resilience and life

satisfaction are related and that positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building on psychological

resilience (Cohn, Fredrickson, Brown, Mikels & Conway, 2009). So, it is possible that differences in

happiness may be explained by psychological resilience which in turn may be explained by positive

emotions (Tugade, Fredrickson, Barret, 2004). It is known that different countries differ by levels of

happiness (e.g. Diener, Suh, Smith, Shao, 1995) and there is a possibility that levels and predictors of

psychological resilience also differ in different countries and regions.

Our study aims to investigate psychological resilience predictors in different European regions –

Western European region, Scandinavian regions and Baltic States. These regions have been chosen

because two of them (Western and Scandinavian) have high levels of economic well-being and

happiness, and the third one shows lower levels of happiness (Eurostat, 2016). We hypothesize that in

different European regions predictors of psychological resilience will differ. The aim of our study is to

investigate relationships between psychological resilience and emotional states – depression, anxiety,

energy and demographic variables such as gender and age.

Research methods

The data from European Social Survey, ESS, (www.europeansocialsurvey.org) round 6 was used to

assess links between psychological resilience and depressive symptoms, anxiety, levels of energy,

gender and age. The European Social Survey (ESS) is an academically driven cross-national survey that

has been conducted every two years across Europe since 2001. ESS monitors social change in Europe

since 2002 .The data is freely available on the website and can be used for non-commercial purposes.

Survey questions have been created by experts, every module includes theoretical background as well

as the argumentation for the need of research. According to survey requirements sampling must be

representative for people aged 15 and over, strict random probability methods must be used at every

stage, substitution of non-respondents is not permitted at any stage.

The dataset of the present study is composed of single-item questions measuring psychological

resilience (“When things go wrong in my life it takes a long time to get back to normal”), where 1

means that a subject agrees strongly with that item and 5 - disagrees strongly, depressive symptoms

(“How much of the time during the past week you felt depressed?”), anxiety (“How much of the time

during the past week you felt anxious?”), energy level (“How much of the time during the past week

you had a lot of energy?”), where 1 means “none or almost none of the time” and 4 means “all or

almost all of the time”. Demographic variables included gender and age.

Resilience refers to “returning to, and speed of return to, a previous level of good functioning

following difficult times or severely disturbing experiences.” (European social survey, 2013, p. 12).

Energy levels refer to the “extent to which people feel like they have a lot of energy” (European social

survey, 2013, p. 18), anxiety refers to a “negative mood condition distinct from depression, and

characterised by fear and concern” (European social survey, 2013, p. 24).

A total number of respondents which were interviewed in 2012 was 17425 (48.4 per cent of males

and 51.6 per cent of females). Respondents’ age was from 15 to 101, but the majority of respondents

were aged 15 to 79 (95.5 per cent). Countries were grouped to Western region (Germany, Switzerland,

France, Belgium, Netherlands), Scandinavian region (Sweden, Denmark, Norway) and Baltic States

(Lithuania, Estonia). Unfotunately, Latvia did not provide data for ESS round 6, so Baltic States group

is not full. Countries to Western region were assigned according to the United Nations classification,

Scandinavian region and Baltic States were assigned according historical and cultural background.

2.1.Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis we used a linear regression model where psychological resilience is a

dependent variable, and depression, anxiety, levels of energy, subjective general health, age, gender are

independent (predictor) variables. The range of Skewness and Kurtosis in psychological resilience was

from -.521 to -.582 which are acceptable to prove the normal data distribution (George & Mallery,

2010).

Findings

Results of psychological resilience relationships to depression, anxiety, energy levels, age and

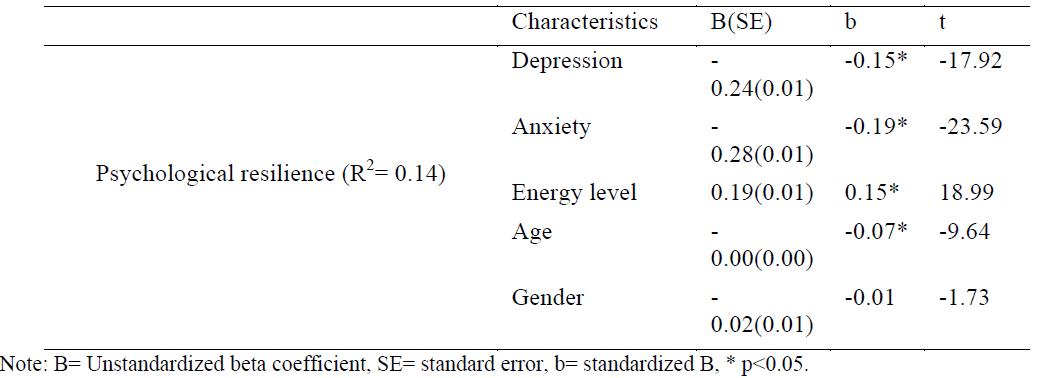

gender in Western Europe region are presented at Table 1.

Results show that in Western Europe region lower levels of depression, anxiety, lower age, higher

levels of energy predicted higher psychological resilience (R2= .14).

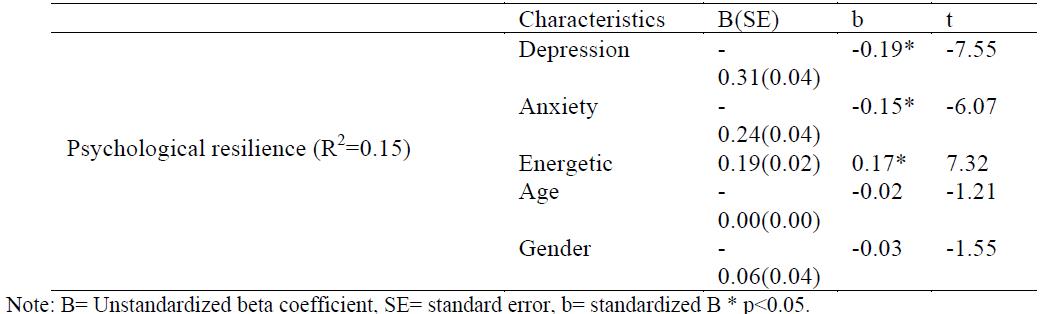

Results of psychological resilience relationships to depression, anxiety, energy level, age and gender

in Scandinavia region are presented at Table 2.

Results from Table 2 demonstrate that in Scandinavian countries lower levels of depression, anxiety,

higher levels of energy predicted higher psychological resilience (R2=0.15).

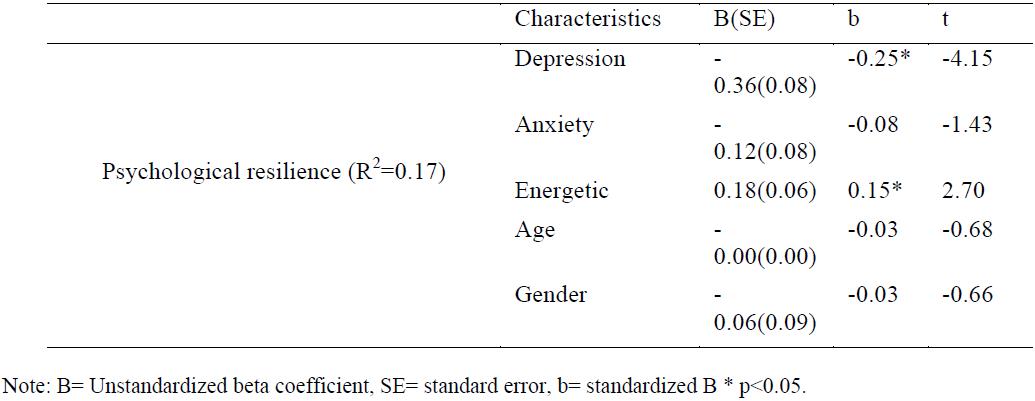

Results of psychological resilience relationships to depression, anxiety, energy level, age and

gender in Baltic region are presented at Table 3.

The results from Table 3 demonstrate that in the Baltic region lower levels of depression and higher

levels of energy predicted higher psychological resilience (R2=0.17).

Conclusions

In the present study we examined links between emotional states (depression, anxiety) and energy

levels), socio-demographic variable (gender, age) and psychological resilience in 3 different European

regions (Western Europe, Scandinavia and Baltic states).

Results demonstrate that predictors of psychological resilience slightly differ in different regions. In

Western Europe only gender does not predict psychological resilience. In Scandinavia gender and age

does not predict psychological resilience. In Baltic States gender, age and anxiety does not predict

psychological resilience. Also in Western Europe anxiety was the strongest predictor of psychological

resilience but in Scandinavia and Baltic States depression was the strongest predictor.

These differences can be explained by different past experiences. Baltic States (Lithuania, Estonia)

as Post-Soviet countries had different cultural experiences in the past than Scandinavian (Sweden,

Denmark, Norway) or Western European (Germany, Switzerland, France, Belgium, Netherlands)

countries. Political and social distrust, lack of freedom and equality, different political system,

mandatory job – it is only a couple aspects of life in the former Soviet Union and these experiences can

possibly affect the current state (Hyyppä, 2010). These long-term and negative experiences can affect

psychological resilience and other psychological constructs as well. It is suggested that politics is

important for recovery of serious disasters (like wars, strong earthquakes) which destroy cities, and

how cities recover from disasters depend on politics as well as culture (Vale & Campanella, 2005). We

assume that politics and culture can affect personal levels of resilience as well. Studies also show that

higher levels of community resilience is related with higher levels of political activity (Poortinga,

2012). In Post-Soviet countries political activity is lower than that of Scandinavian or Western

European countries (Letki, 2003) and this can be one possible explanation why citizens of Baltic States

differ from Scandinavians or Western Europeans by their level of psychological resilience and its’

predictors. However there is a need for further investigations at country levels for understanding how

political activity, as well and political system can affect psychological resilience and, probably, other

psychological constructs.

In general, the study showed that Western European, Scandinavian and Baltic States differ by

predictors of psychological resilience. In all three regions only lower levels of depression and higher

levels of energy predicted higher psychological resilience.

References

- Bonanno, G. A., Galea, S., Bucciarelli, A., & Vlahov, D. (2007). What predicts psychological resilience after

- disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 75(5), 671-682.

- Jarašiūnaitė, G., Kavaliauskaite-Keserauskienė, R., & Perminas, A. (2012). Reaction to an audiovisual stressor and health risk behavior in individuals having a type behavior pattern. Journal of young scientists. 2(35), 42-48. Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer publishing company.

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events?. American psychologist, 59(1), 20-28.

- Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2013). Psychological Resilience. European Psychologist, 18(1), 12-23.

- Leipold, B., & Greve, W. (2009). Resilience: A conceptual bridge between coping and development. European Psychologist, 14(1), 40-50.

- Davydov, D. M., Stewart, R., Ritchie, K., & Chaudieu, I. (2010). Resilience and mental health. Clinical psychology review, 30(5), 479-495.

- Tugade, M. M., Fredrickson, B. L., & Barrett, F. L. (2004). Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. Journal of personality, 72(6), 1161-1190.

- Bonanno, G. A., Galea, S., Bucciarelli, A., & Vlahov, D. (2006). Psychological resilience after disaster New York city in the aftermath of the September 11th Terrorist Attack. Psychological Science, 17(3), 181-186.

- Pietrzak, R. H., & Southwick, S. M. (2011). Psychological resilience in OEF–OIF Veterans: Application of a novel classification approach and examination of demographic and psychosocial correlates. Journal of affective disorders, 133(3), 560-568.

- Pietrzak, R. H., & Cook, J. M. (2013). Psychological resilience in older US veterans: results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. Depression and anxiety, 30(5), 432-443.

- Pietrzak, R. H., Johnson, D. C., Goldstein, M. B., Malley, J. C., & Southwick, S. M. (2009). Psychological resilience and postdeployment social support protect against traumatic stress and depressive symptoms in soldiers returning from Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Depression and anxiety, 26(8), 745-751.

- Gooding, P. A., Hurst, A., Johnson, J., & Tarrier, N. (2012). Psychological resilience in young and older adults. International journal of geriatric psychiatry, 27(3), 262-270.

- Klohnen, E. C. (1996). Conceptual analysis and measurement of the construct of ego-resiliency. Journal of personality and social psychology, 70(5), 1067-1079.

- Tugade, M. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of personality and social psychology, 86(2), 320-333.

- Hassink, R. (2009). Regional resilience: a promising concept to explain differences in regional economic adaptability?. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 45-58.

- Sheffi, Y. (2005). The resilient enterprise: overcoming vulnerability for competitive advantage. MIT Press Books, 1. Vale, L. J., & Campanella, T. J. (2005). The resilient city: How modern cities recover from disaster. Oxford University Press.

- Cohn, M. A., Fredrickson, B. L., Brown, S. L., Mikels, J. A., & Conway, A. M. (2009). Happiness unpacked: positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion, 9(3), 361-368.

- George, D., & Mallery, M. (2010). SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 17.0 update (10a ed.) Boston: Pearson.

- ESS Round 6: European Social Survey Round 6 Data (2012). Data file edition 2.2. Norwegian Social Science Data Services, Norway – Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC.

- European Social Survey (2013) Round 6 Module on Personal and Social Wellbeing – Final Module in Template. London: Centre for Comparative Social Surveys, City University London.

- Eurostat. Quality of life in Europe - facts and views - overall life satisfaction. Retrieved April 04, 2016, from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Quality_of_life_in_Europe_-_facts_and_views_-_overall_life_satisfaction Hyyppä, M. T. (2010). Healthy ties: Social capital, population health and survival. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Poortinga, W. (2012). Community resilience and health: The role of bonding, bridging, and linking aspects of social capital. Health & place, 18(2), 286-295.

- Letki, N. (2003). Explaining political participation in East-Central Europe: social capital, democracy and the communist past (No. 381). Centre for the Study of Public Policy, University of Strathclyde.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

14 May 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-007-5

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

8

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-252

Subjects

Psychology, social psychology, group psychology, collective psychology, teaching, teaching skills, teaching techniques

Cite this article as:

Smitas, A., & Gustainienė, L. (2016). Is resilience related to depression, anxiety and energy? European Social Survey results. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences - icCSBs 2016, May, vol 8. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 125-130). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.05.12