Abstract

The present study aims to explore the attributes of interpersonal relationships, as a socio-psychological dimension, and their beneficial or detrimental effects on locally specific participatory processes in a Turkish context. Following this, an analysis of the effect of the relationship on locally specific participatory processes is presented, through a comparative assessment of processes in four local cases which were partners of the Local Government & NGO Cooperation in Participatory Democracy Project. This research, designed as an exploratory case study, determines some of the unexplained factors affecting participatory processes. Finally, the study reveals that, relationships, change in relationships, trust, rivalry, dominance, hidden agendas and jealousy are all perceived attributes of the interpersonal relationship dimension in the Turkish context. While the interpersonal relationship dimension enhanced the participatory process in two of the four cases (Odunpazarı and Seyrek), it hindered the participatory process in Gazi and Kaymaklı.

Keywords: participation, participatory process, interpersonal relationship, local government, Turkish context

Introduction

Interpersonal relationship is a basic socio-psychological dimension of participatory processes, since

participation is an interaction among participants and the participatory process is initiated by

individuals and their interaction with each other (Kulözü, 2016). Aside from the concept of trust, other

attributes of interpersonal relationships have not been focused on or explored as socio-psychological

attributes of participatory processes, except for an article written by Kulözü & Tekeli (2014), which

focused on the socio-psychological dimensions of participatory processes. Furthermore, neither the

effects of the relationship dimension nor the effects of its attributes on the processes have been

explored or examined.

This study generally aims to answer two questions, including, ‘what are the perceived interpersonal

relationship attributes and their beneficial or detrimental effects on participatory processes in a Turkish

context?’ and ‘how does the interpersonal relationship dimension affect contextually different

participatory processes? The study was designed to be exploratory in nature. Along the same line as

Kulözü (2016), the claim of this exploratory case study is the fact that the varying dimensions of

participatory processes should be determined. Only after all aspects are understood can steps be taken

to design and conduct the most beneficial participatory process.

Despite the absence of particularly relevant literature, this study intends to explore a number of

issues, which includes: the attributes of the interpersonal relationship dimension in a Turkish context,

the beneficial or detrimental effects of the explored attributes of the Local Government & NGO

Cooperation in Participatory Democracy Project process, the beneficial or detrimental effects of the

interpersonal relationship dimension on participatory processes in Gazi, Kaymaklı, Odunpazarı and

Seyrek, since they were partners in the participatory project case.

Accordingly, the study is presented in four main sections. First, the theoretical framework focuses

on the key concepts for the study, including participation, participatory processes, contextual

differences and interpersonal relationship dimension in both participation and social sciences

literatures. Second, the case project of the study and the case municipalities are introduced to allow an

understanding of their contextual characteristics. Following a presentation of the methodology, the

findings of the research are presented under two headings: the findings of the case project, and the

findings of contextually different participatory processes. Finally, the findings of this study are

interpreted in the conclusion.

Theoretical Framework

2.1.Participation and Participatory Processes

Participation refers to the direct involvement of the public in decision-making processes through a

range of formal and informal mechanisms. As proponents of participation and participatory practices,

Wondolleck & Yaffee (2000) argue that, participation leads to better decisions. Similarly, Fung &

Wright (2003) state that, participation can lead to effective and equitable solutions while increasing the

capacity of the public for self-governance. Participatory approaches are discussed as being more

democratically accountable than traditional, representative and instrumental approaches. Opposing the

instrumental approaches, as stated by Cooke & Kothari (2001), the professed aim of participatory

approaches is to make people more central to development, by encouraging the beneficiaries to become

involved in the decisions and processes that affect them, especially decisions and processes over which

they previously had only limited control or influence.

Global trends toward participation and participatory practices began to appear in both literature and

practice during the second half of the 20th century. The concept of participation has attracted

researchers from a broad range of academic disciplines. Because of this trend, focus shifted from

outputs, such as plans and/or policies, to participatory processes in the field, such as public

management, planning and political sciences.

The process is of particular importance in the participatory approach, as it not only takes into

account the specific content of issues, but also considers how issues are discussed, how problems are

defined and how problem-solving strategies are articulated (Kulözü & Tekeli, 2014). Unlike the

traditional approach, a participatory process aims to help communities invent their own participatory

processes rather than providing a set of procedures to be followed. Therefore, the result is that there are

locally specific processes that cause some locals to be more favourable to the management of

participatory processes than others (Healey, 1997; Kulözü, 2016). In short, every single participatory

process is locally specific and unique to the context where the process is conducted (Kulözü & Tekeli,

2014).

As discussed by Kulözü (2016) and Kulözü & Tekeli (2014), the uniqueness of participatory

processes comes not only from contextual differences, but also from the different social actors and their

interaction during the process. Various social actors, which have assorted connections with each other,

take part in participatory processes. As a result, participants, their participation patterns and the pattern

of interactions among them illustrate the differences for each participatory process. These differences

lead to unique experiences in a participatory process. Generally, the individuality of a participatory

process could be explained based on three components: the individual/society, the context, and the

process itself (Kulözü & Tekeli, 2014; Kulözü, 2016). Interaction between these components in a

participatory process stimulates the social influence process. Social influence is an intrinsic element of

participatory processes, in terms of its transformative power to invoke changes in an individual’s

feelings, thoughts, attitudes, behaviours and interactions during the process. Through social influence

resulting from changes within a context, socio-psychological dynamics become effective in

participatory processes (Kulözü, 2016). However, since social influence is a chief research area in

social psychology (Dunn, 2008), the type of social influence that occurs in the participatory process

could be explored with the knowledge already gained in the area of social psychology and other social

sciences. Socio-psychological dynamics constitute a part of the subtle reality behind participatory

processes and are of paramount importance (Kulözü & Tekeli, 2014; Kulözü, 2016). As one of the key

aspects of the socio-psychological dimension, interpersonal relationships will be examined in the

following section.

2.2.The Interpersonal Relationship Dimension and Its Attributes

Although the common aim of every participatory process is to reach a consensus, with or without

consensus however, each participatory process is unique (Kulözü & Tekeli, 2014). Participatory

processes are galvanised by the participants and their interactions, because individuals come together to

reach a consensus on decisions or policies during the process. Each participatory process is conducted

in a unique socio-cultural context and has its own pattern of interaction that is created by the

participants. Therefore, participatory processes are subject to socio-psychological phenomena, such as

interpersonal relationships. Each participatory process and its achievements are determined by the

effect of its individual socio-psychological dimensions (Kulözü, 2014; Kulözü & Tekeli, 2014).

Participation is the interaction between participants. During the participatory process, interactions

among individuals, whether they previously know each other or not, create an interpersonal

relationship. Interpersonal relationship is a product of two parties who participate in an interaction

(Bateson, 1972; Kulözü & Tekeli, 2014). During participatory processes, social actors learn about each

other through interactions that result in new interpersonal relationships. In addition to a new

interpersonal relationship, an established interpersonal relationship could be changed during the

process as a side effect of the process, as well as other dimensions of the process and process

participants. However, the relationship dimension and participatory process flows is not always one-

way, but mutual. Because the interpersonal relationship dimension affects the participatory process and

its outcomes by playing a role in people’s efforts to persuade others or effect changes in their attitudes

during the participatory process (Kulözü & Tekeli, 2014). In other words, it affects both the

participatory process and other socio-psychological dimensions, including communication, power and

conflict. However, the present study is only focused on the interpersonal relationship dimension of

participatory processes alone.

Interpersonal relationship is one of the basic socio-psychological dimensions of participatory

processes, as it forms the basis of other interactional dimensions (Kulözü & Tekeli, 2014). Although

there are relatively few studies that focus on this issue, interpersonal relationship has a special role

within participatory processes. In this section, the issues related to interpersonal relationships that have

already been covered both in the participation literature, and also in the review of findings, as well as

the social sciences literature are presented, to determine the pre-defined interpersonal relationship

attributes. These pre-defined attributes are used to explore the attributes of interpersonal relationship

dimensions from the perspective of the participants.

A review of participation literature revealed that, although the concept has not been discussed as an

attribute of interpersonal relationship, ‘trust’ (Carnes et al. 1998; Bentrup, 2001; Webler, et al. 2001;

Schulz, et al. 2003; Bickerstaff, 2004; Dowling, et al. 2004; Tippett, et al. 2005; Pascaru & Buţiu,

2010) is one of the most discussed socio-psychological phenomena, not just as an attribute of

interpersonal relationship. In addition to trust, Hagmann et al. (1999) highlight the concept of ‘entering

the community’ (participants from out of the selected location); McCool & Guthrie (2001) discuss the

idea of ‘relationship building’; Cooper (2002) demonstrates the notion of a ‘hidden agenda’, all of

which could be evaluated under the interpersonal relationship dimension (Kulözü & Tekeli, 2014). In

short, the review of participation literature shows trust, relationship building and hidden agenda to be

attributes of the interpersonal relationship dimension. However, before examining the enhancing and/or

limiting effects of these attributes on participatory processes, social sciences literature should be

reviewed to understand how these concepts are engaged with, and then determine interpersonal

relationship attributes, by applying knowledge from both areas of study.

A review of social sciences literature showed that there are two basic types of interpersonal

relationships: symmetrical and complementary relationships (Bateson, 1972). If the behaviours of two

individuals are regarded as similar, there is a symmetrical relationship between them, and such a

relationship can be demonstrated through friendship. However, a complementary relationship is where

the behaviour of the two individuals are dissimilar, they mutually complement each other, such as in a

dominance-submission and nurturance-dependence situation. Within participatory processes, the

effects of symmetrical and complementary relationships on friendships as a symmetrical relationship,

and dominance-submission as complementary relationship and their effects on participatory processes

could be examined. Therefore, the ‘type of relationship’ could be determined as a pre-defined

relationship attribute.

In addition to the types of interpersonal relationships, the change in interpersonal relationship

pattern clarification is also important for the present study. Since the participatory process is accepted

as a socially influential process, the influence of the process and the interactions during the process on

interpersonal relationships can be explored by examining the changes in interpersonal relationships.

Although interpersonal relationships change over time, as it can be seen within our own everyday

experiences, they are sometimes extremely resistant to change. In terms of the propensity of

interpersonal relationships to change and resist, relationships are categorised as habitual, self-

amplifying and self-validating. Interpersonal relationships have habit-forming effects on the

individual’s behaviour and create a propensity to act towards another person in a certain way, while

self-amplifying is used to explain mutual reinforcement in the context of an interpersonal relationship.

In a self-validating relationship pattern, even if one party attempts to change the relationship by

adopting a different style of interaction, the other party might perceive incorrectly by believing that the

new behaviour is simply a continuation of a previously established pattern (Bateson, 1972).

Discussions on the building of new interpersonal relationships and changing patterns of interaction

reveal that, the habit forming effect of a relationship, competitive relationships, resistance to change,

and their effects on the participatory processes could be defined as interpersonal relationship attributes.

A review of the participation literature portrays trust as a special type of interpersonal relationship,

because it is the only attribute of the interpersonal relationship dimension to be discussed and

examined. In fact, trust is one of the most discussed socio-psychological attributes in the participation

literature. However, there are different definitions of trust. One approach of defining trust as the

outcome of subjective probability calculation of risk involves evaluating the other party in terms of

his/her trustworthiness (Zucker, 1987); another approach conceives trust as socially embedded, and

argues that trust emerges as symmetrical pattern of interaction (Anheier & Kendall, 2000: 8). Trust

plays an important role in determining the types of influence they are able to exert over one another

and the type of relationship that already exists among the participants. A participatory process without

trust could create suspicion, such as a ‘hidden agenda’. A hidden agenda, related to the power

dimension, could be defined as keeping certain items off the agenda so that a chance for others to exert

their influence never arises. A hidden agenda is one of the most important issues related to trust and

interpersonal relationship in the participatory processes. Therefore, as a socio-psychological attribute,

trust could help explain many other socio-psychological attributes of participatory processes. In the

context of participatory processes, trust between actors of the process that have different interests have

critical importance.

The issues that are discussed in the field of social psychology and participation related to

interpersonal relationships are determined in this study. While trust, hidden agenda, and relationship

building attributes have been discussed within the context of the participation literature, the others have

not been previously discussed. Based on these sub-issues, such themes including friendships,

dominance and submission, competitive relationship, the habit forming effects of the relationship

developed within the participatory process, resistance to change, trust and hidden agenda are

determined as the attributes of the relationship dimension. Through these evaluations, issues related to

the interpersonal relationship dimension are presented by clarifying their roles within the participatory

process.

This study intends to explore the perceived attributes of interpersonal relationships and their

beneficial and/or detrimental effects on locally specific participatory processes. Therefore, in the

following section, the case project and the case sites where the project was conducted, as well as the

method of the study are presented.

Case Study

3.1.The Local Government & NGO Cooperation in Participatory Democracy Project

In Turkey, a law that allows local administrations to create city councils, which also allows NGOs

to participate actively in local decision-making mechanisms, was passed with the enactment of the

Local Administrations Code [TBMM (the Grand National Assembly), no: 5355, ratified on 26 May

2005]. Based on this law, citizens are allowed to participate in the administration of the city, Civil

Society Development Center (CSDC) designed the Local Government & NGO Cooperation in

Participatory Democracy Project. CSDC (2005) launched the project that would serve as a guide in

participatory administration given the lack of experience in the Turkish context. The purpose of the

project is defined as “enabling local administrations to create participatory administration structures in

cooperation with the NGOs in their area” (Kulözü, 2014; Kulözü, 2016).

The project was conducted by CSDC with the financial support of the European Commission

(CSDC, 2005). The project was launched with the participation of local municipalities in Turkey

including Gazi, Kaymaklı, Odunpazarı and Seyrek, in cooperation with NGOs between 2005 and 2007.

During the project process, CSDC organised meetings to provide a platform for the partners to come

together to share their experiences within each of their participatory processes. In the interim periods

between these meetings, each municipality worked with the support of the CSDC in order to create

participatory administration structures that shifted from management to participatory decision-making

processes (Kulözü, 2014; Kulözü, 2016). To reach their goals, the CSDC provided technical and

educational support for each municipality geared towards their own individual situation. Although the

objective of each locality was the same for the partner in each of the case projects, due to their

contextual differences each partner locally designed their own participatory process.

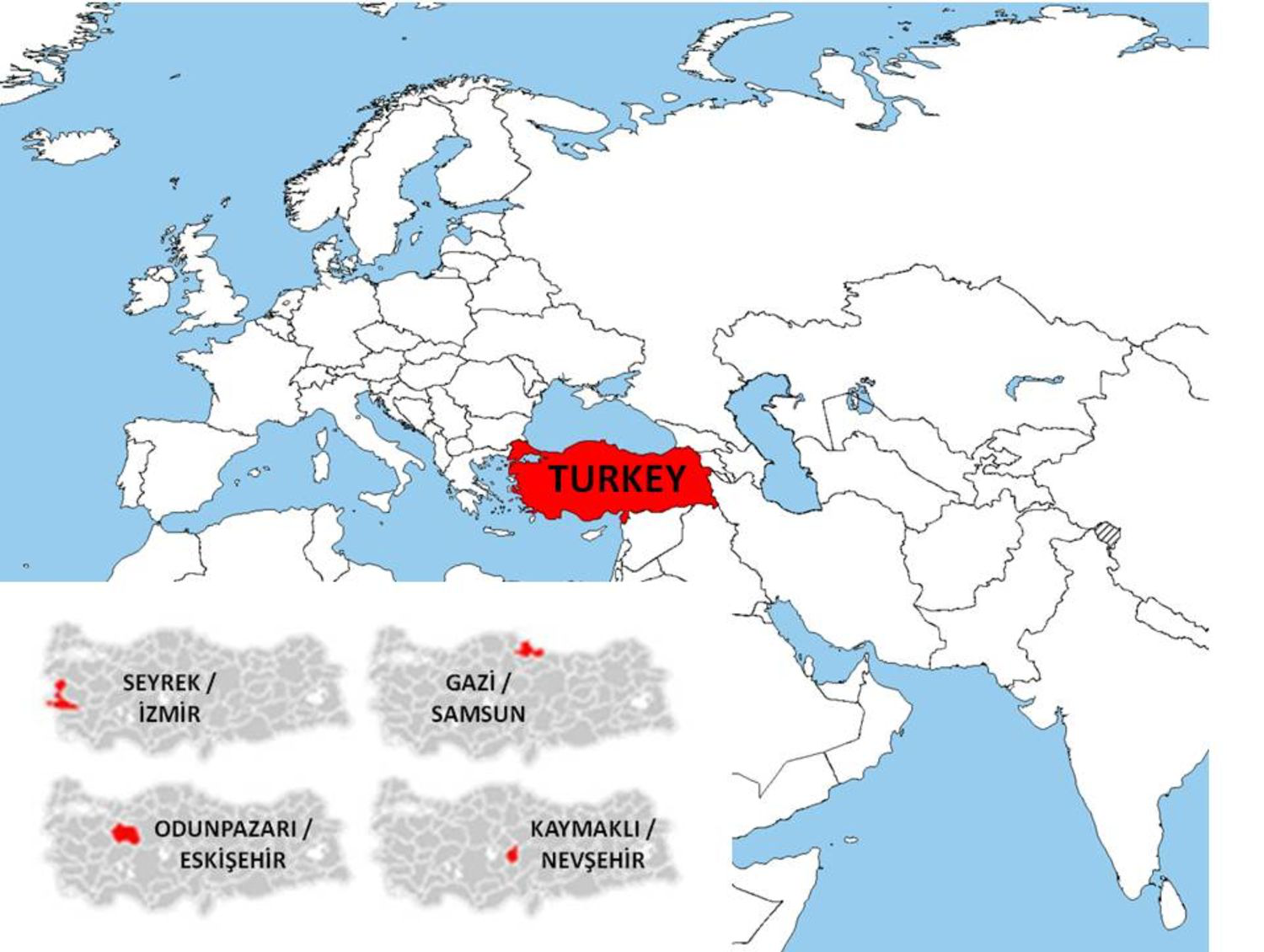

3.2.Contextual Differences of the Case Areas: Gazi, Kaymaklı, Odunpazarı and Seyrek

Each municipality case reveals geographical differences parallel to their individual social, cultural,

economic, political contexts within Turkey (Kulözü, 2016) (Fig. 1). Kaymaklı and Seyrek are town

municipalities. Seyrek, with a population of 3,865, is a district of İzmir that is located in the Aegean

Region. Kaymaklı, with a population of 5,811, is located in the Central Anatolian Region. Gazi, with a

population of 139,962, is located in the Black Sea Region, and Odunpazarı, with a population of

274,038, is located in the Central Anatolian Region. Gazi as well as Odunpazarı are considerably larger

municipalities in terms of population, compared to Seyrek and Kaymaklı. In terms of their socio-

economic development levels, according to a report by the State Planning Organisation (2004),

Odunpazarı, a central-metropolitan district of Eskişehir, was ranked seventh in terms of development,

of the 872 districts across Turkey. Gazi, a central-metropolitan district of Samsun, was ranked 25th.

Kaymaklı, as one of the central districts of Nevşehir, was ranked 89, while Seyrek, a sub-district

municipality of Menemen/İzmir, was ranked 142 out of the 872 districts (State Planning Organisation,

2004; Kulözü, 2014; Kulözü, 2016). Parallel to their socio-economic development level, the

development of civil society in each of the locations were also different. That resulted in differences in

terms local participants in the project meetings. In Odunpazarı and Gazi, NGO representatives

participated. In Seyrek and Kaymaklı, only individual local stakeholders participated, meaning there

were no NGOs at the start of the project in 2005 (Kulözü, 2016).

Research method

This research was designed as an exploratory case study, and the field study was conducted in Gazi

(Samsun), Kaymaklı (Nevşehir), Odunpazarı (Eskişehir) and Seyrek (İzmir) between August 2011 and

January 2012. During the field study, 45 participants from the case project from all four locations were

interviewed. The interviews were conducted in an in-depth manner. The respondents were selected

from among the participants of the project process and attended at least one of the key meetings

organised by the CSDC. Since the participant numbers varied in each case, the number of respondents

interviewed also varied. The limitation of the present study was addressed by presenting the

quantitative results of analyses for each case as an average per person. As a result, the 45 interviews

conducted during the field study were distributed among the locally specific participatory processes as

follows: 14 from Kaymaklı, 13 from Seyrek, 11 from Odunpazarı and 7 from Gazi.

During the interview, open-ended questions were posed to the respondents, and the interviews were

reported and recorded. The questions included: ‘what was your experience regarding interpersonal

relationships during the participatory process?’ and ‘how did the interpersonal relationship affect the

participatory process?’ In order to analyse the collected qualitative data, a content analysis method was

used. Through content analysis, the perceived interpersonal relationship attributes were explored based

on the subjective descriptions of the respondents. The collected qualitative data is then translated into a

quantitative form, through the use of multivariate statistical analysis techniques in classifying the data.

In addition to quantifying the specific issues, a content analysis was used to explore whether the

respondents considered their effects to be detrimental or beneficial for both the case project and the

locally specific case processes, along the same lines of Kulözü (2016). Therefore, when assigning the

replies of the respondents into content categories, not only was the frequency of mention of each

perception recorded, but also whether respondents mentioned the issues and their effects on the process

in a positive or negative way. As a result, through content analysis, the attributes of the relationships

and their detrimental or beneficial effects on the participatory process were also determined by

comparing the differences between the frequency of negative and positive comments.

Findings

5.1. Attributes of interpersonal relationship dimension and their effects on the case project process

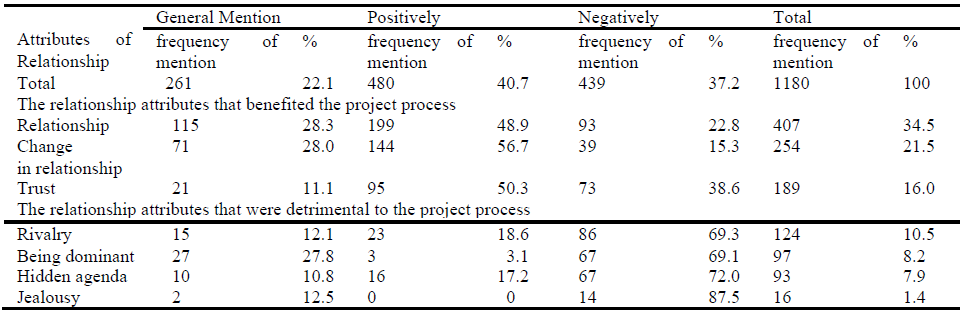

The research determined seven perceived relationship attributes from both participation and social

sciences literature, including friendships, dominance and submission, competitive relationships, habit

forming effects of the relationship developed within the participatory process, resistance to change,

trust and hidden agenda. The empirical study included interpersonal relationships, change in

interpersonal relationships, trust, rivalry, dominance, hidden agenda and jealously. These were

explored as the perceived attributes within the interpersonal relationship dimension. Table 1 reveals

how often each perceived attribute was mentioned for the total sample, and shows whether it was

mentioned in a general, positive or negative way. According to the findings, the interpersonal

relationship dimension was mentioned 22.1% of the time with a general connotation, 40.7% of the time

with a positive connotation, and 37.2% of the time negatively. It means that the interpersonal

relationship dimension was referred to in more beneficial terms (40.7%) than detrimental (37.2%) in

the case of the Local Government & NGO Cooperation in the Participatory Democracy Project.

Table 1 puts the relationship attributes into two groups. First, the attributes that enhanced rather

than hinder the process; and second, the attributes that hindered rather than enhance the process. The

research revealed that the three relationship attributes which enhanced the project process were, change

in relationships, relationships, and trust, while the other four relationship attributes that hindered the

process were rivalry, being dominant, hidden agenda and jealousy.

5.1.1. Relationship

The analysis showed that interpersonal relationship, being the most cited attribute, is an effective

attribute of the participatory process. The interpersonal relationship attribute was cited almost one-third

of the time (34.5%). Symmetrical relationship, importance and unimportance of the relationship in the

participatory process, the effects of individuals on the relationship, how a relationship should be, the

effort and time that were used to develop relationships, what was necessary to develop relationships,

the effects of the relationship on the process (both positive and negative), the continuity and

discontinuity of relationships, the effects of politics on the interpersonal relationship and the effects of

the process on the interpersonal relationship, and the effects of all of these issues on the participatory

process, were all categorised as an interpersonal relationship attribute of the analysis process. For the

total sample, interpersonal relationship was mentioned 28.3% of the time in general, 48.9% of the time

positively, and 22.8% of the time negatively. Since, the interpersonal relationship attribute was cited

frequently in positive terms, the attribute was considered to be beneficial to the process rather than a

hindrance. The following quotation exemplified relationship attributes and their positive effects on the

case project process:

“The process was affected more by the relationship. For instance, the most important asset of our initiative was the high number of participant NGOs, whose participation was based on their relationship with other participants. For the individual participants, our initiative, the CSDC or the municipality were not important. What was important for the future participants was the person who called them to the meetings or organisations. The people at the centre built an atmosphere of trust in their social environment and used their social networks… after participating one time, a person would continue to participate, it became a habit; but the first step was very important, and it was based on forming a relationship” (a respondent (Odunpazarı), 07.08.2011).

5.1.2. Change in Relationship

The analysis revealed that a change in interpersonal relationship, as the second most cited attribute,

is an effective attribute in the participatory process. For the total sample, the attribute was cited nearly

one-fifth of the time (21.5%). During the analysis process, a change in the interpersonal relationship

was realised and was not realised, change should be realised, resistance to change, change in the

interpersonal relationship of men-women and the effects of the change in the interpersonal relationship

on the process were all categorised under the change in relationship attribute. For the total sample,

change in relationship was mentioned 28% of the time in general terms, 56.7% of the time positively,

and 15.3% of the time in negative terms. It is revealed that, a change in the interpersonal relationship

was considered to be beneficial to the process. The following citation exemplified change in

relationship attribute with its positive effects on the case project process:

“Relationship changed very much. For instance, I became a good friend with a participant who was a member of a religious group. If we had met before the participatory process, I would be unlikely to talk with him, and [at first] I even did not want to sit with him. The changes in relationship provided for the sustainability of the process” (a respondent (Odunpazarı), 07.08.2011).

5.1.3. Trust

The findings revealed that trust, as the third most cited attribute, is an effective attribute in the

participatory process. Within the total sample, trust was cited almost one-sixth (16%) of the time.

During the analysis process, the way of building trust, the importance of trust, the importance of trust

to central persons, there was trust and was no trust, trust increased and decreased during the process

and the effects of trust on the process were all categorised under the trust attribute. Within the entire

sample, trust was mentioned 11.1% of the time in general terms, 50.3% of the time in positive terms,

and 38.6% of the time in negative terms. Therefore, trust was considered to be beneficial to the process

rather than a hindrance. The following remark exemplified trust attribute and its’ negative effect on the

participatory process:

“If trust could have been created among the people in the women’s cooperative, and if we could have worked to a successful outcome, the workshop could have been continued. There was neither trust nor success … I did not trust anybody during the process. In particular, I did not trust any of the central people” (a respondent (Kaymaklı),13.10.2011).

5.1.4. Rivalry

The analyses showed that rivalry is an active interpersonal relationship attribute in participatory

processes. The attribute was cited almost one-sixth (10.5%) of the time within the total sample. Rivalry

was in the process and was not, the effect of rivalry on the process in positive and negative terms were

all categorised under the rivalry attribute in the analysis process. Within the entire sample, rivalry was

mentioned 12.1% of the time in general terms, 18.6% of the time in positive terms, and 69.3% of the

time negatively. This reveals that the rivalry attribute was typically cited in terms of its detrimental

effects on the participatory project process. The following interview exemplified a rivalry attribute and

its negative effect on the participatory process:

“There was too much rivalry. The conflict of interest was at such a level that some of the participants became like enemies. As a result, the participants separated into groups, which were detrimental to the continuity of the process” (a respondent (Kaymaklı), 13.10.2011).

5.1.5. Being Dominant

The findings showed that dominance is an interpersonal relationship attribute in participatory

processes. The attribute was cited 8.2% of the time within the total sample. During the analysis, there

was being dominant and there was none, the reaction to the dominant participants and the effects of

being dominant on the process were all categorised under the dominant attribute. Within the entire

sample, this attribute was mentioned 27.8% of the time in general terms, 3.1% of the time positively,

and 69.1% of the time in negative terms. This shows that dominant attributes were commonly

mentioned in terms of its detrimental effects on the participatory project process. The following citation

exemplified dominant attribute and its negative effect on the participatory process:

“There was a secretary of the mayor who took over the mayor’s responsibilities in his absence. He was very dominant. He said ‘They don’t know anything, I don’t care about them’. There were unwritten rules based on the whim of the mayor’s secretary. If he did not approve of something, it would not be realized” (a respondent (Gazi), 25.10.2011).

5.1.6. Hidden Agenda

The findings revealed that hidden agenda, cited 7.9% of the time in the total sample, is an

interpersonal relationship attribute in the participatory process. The importance of a hidden agenda,

there were hidden agendas and there were none, and the effects of hidden agenda on the participatory

processes were all categorised under the continuity of interpersonal relationship attribute in the

analysis. Within the entire sample, the attribute was mentioned 10.8% of the time in general terms,

17.2% of the time positively, and 72% of the time negatively. Meaning that the hidden agenda attribute

was primarily cited in terms of its detrimental effects on the project process. The following citation

exemplified hidden agenda attribute and its negative effect on the participatory process:

“Some participants came to meetings with hidden agendas. I think they used the participatory process to boost their political identities. This led some participants to discontinue their involvement in the process” (a respondent (Odunpazarı), 09.08.2011).

5.1.7. Jealousy

The analysis showed that jealousy, which was cited 1.4% of the time in the total sample, is an

interpersonal relationship attribute of the participatory processes. During the analysis, there was no

jealousy and there was jealousy, and the effects of jealousy on the process were all categorised under

the jealousy attribute. In the entire sample, jealousy was mentioned 12.5% of the time in general terms

and 87.5% in negative terms. This results show that the jealousy attribute was primarily mentioned in

terms of its detrimental effects on the participatory project. The following citation exemplified jealousy

attribute and its negative effect on the participatory process:

“The fact that our participatory process was unsuccessful was not related to management, as it was rather attributable to jealousy among individuals. There was little cooperation among the women, as they were jealous. For this reason we could not create an atmosphere of togetherness” (a respondent (Kaymaklı), 12.10.2011).

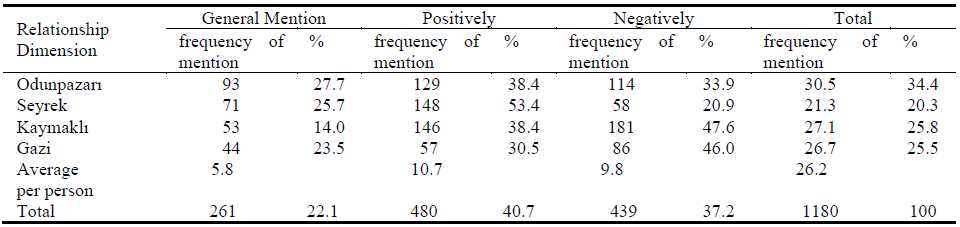

5.2. Comparing the Effects of Interpersonal Relationship Dimension on the Locally Specific Participatory Processes

Table 2 presents the interpersonal relationship dimension in three groups: based on their neutral,

beneficial and detrimental effects for the participatory processes conducted in Gazi, Kaymaklı,

Odunpazarı and Seyrek. An analysis that focuses on the difference in the ratio of positive and negative

references of the four case processes individually revealed that, while the relationship dimension is

considered to have enhanced the participatory processes of Odunpazarı (38.4–33.9%) and Seyrek

(53.4–20.9%), it hindered the participatory processes of Gazi (30.5–46%) and Kaymaklı (38.4–47.6%)

from the perspective of participants.

Evaluating the hindering and enhancing effects of the interpersonal relationship dimension in

association with the development levels of the cases did not yield any significant result. Findings based

on the respondents’ subjective descriptions reveal that the interpersonal relationship dimension affected

the participatory process in the most and least developed cases positively, and it affected the other two

cases negatively. This reveals that, there is no correlation between the hindering and/or enhancing

effects of the interpersonal relationship dimension and the socio-economic development levels of the

cited cases. Despite not being a focus of this study, there could be a correlation between the

interpersonal relationship dimension and other dimensions at the micro level, such as psychological

dimensions, and with dimensions at the macro level, including other socio-psychological and cultural-

contextual dimensions.

Conclusions

The present case study aimed to explore some of the unexplained factors affecting participatory

processes, by focusing on the interpersonal relationship dimension. The study was designed with the

purpose of exploring the factors affecting the participatory processes, which are of critical importance

in our increasingly democratised world. In our contemporary society, communities need to collaborate

when making decisions on behalf of the individual, society and the environment. By exploring

unexplained factors affecting participatory processes, a path may be discovered for more successful

participatory practices.

This exploratory research revealed that, while the only discussed interpersonal relationship

attributes in the participation literature had been trust (along with some relationship building and

hidden agenda), interpersonal relationship, a change in interpersonal relationships, trust, rivalry,

dominance, hidden agenda and jealousy are also perceived to be attributes of the interpersonal

relationship dimension. The study, in terms of the effects of the contextual differences, determined that

while the interpersonal relationship dimension is perceived to have enhanced the participatory

processes in two cases (Odunpazarı and Seyrek), it is perceived to have hindered the processes in Gazi

and Kaymaklı. Alternatively, the extent to which the interpersonal relationship dimension enhanced the

contextually different participatory processes was different for the two enhanced case processes,

indicating the importance of context on participatory practices.

As a result of these findings, the present study established a framework of the interpersonal

relationship dimension and its attributes in a Turkish context. Such a framework clears a path for the

exploration of their enhancing or limiting effects by considering that, the attributes and interpersonal

relationship dimension could be altered before and during a participatory process. The interpersonal

relationship attributes could be categorised based on, whether or not they could be subject to alteration,

have enough time that is required to make an intercession and achieve the desired results. While some

interpersonal relationship attributes, including hidden agenda, rivalry, and jealousy, cannot be

subjected to change (or may take too long to change), trust, dominance and change in relationship may

be altered within a relatively short period of time in the context of a participatory process.

The determination of the interpersonal relationship attributes and the means of intervention are of

critical importance, as it may open a pathway to establish the frame in which the required actions can

take place before or during the participatory process. However, due to the contextual differences and

uniqueness of each participatory process, it is not possible to determine a single accurate answer with

regard to how and when to intervene. It should be considered that the relationship dimension and its

attributes affect each participatory process in its own way, and is dependent on the uniqueness of each

participatory process and its context, as is explored in this study. Therefore, intervention should be set

in motion based on the need of each context by enhancing the beneficial effects of the interpersonal

relationship and its attributes, and more importantly by decreasing the hindrances. Efforts to determine

which of the areas and which actions can be initiated against the obstacles of the participatory

processes would increase the likelihood of a more democratic and successful participatory experience.

In sum, by exploring the attributes of interpersonal relationship in the participatory processes, along

with their detrimental and beneficial effects on participatory process in a Turkish context, and changing

the effects of the interpersonal relationship dimension on locally specific participatory processes, this

research has presented a framework for researchers, managers of local governments, and participatory

process designers and facilitators, in line with the sample set forth by Kulözü (2016). Subsequently,

other socio-psychological dimensions and their attributes may be studied to develop our understanding

about the socio-psychological dimensions of participatory processes in different contextual settings,

and their changing effects on locally specific participatory processes.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a revised and updated part of the author’s PhD thesis ‘Socio-Psychological

Dimensions of Participatory Processes: In the Case of Local Government and NGO Cooperation in

Participatory Democracy Project’ that was awarded the ‘Best Thesis of the Year’ in 2011-2012 at the

METU. The thesis was supported by the State Planning Organization (DPT) Grant No: BAP-08-11-

DPT.2011K121010.

References

Anheier, H. K. & Kendall, J. (2000). Trust and voluntary organizations: Three theoretical approaches. Civil Society Working Paper 5. Retrieved from http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/29035/1/CSWP5web-version.pdf.

Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind. New York: Ballantine Books.

Bickerstaff, K. (2004). Risk perception research: socio-cultural perspectives on the public experience of air pollution. Environment International, 30, 827-840.

Bentrup, G. (2001). Evaluation of a Collaborative Model: A Case Study Analysis of Watershed Planning in the Intermountain West. Environmental Management, 27 (5), 739-748.

Carnes, S. A., Schweitzer, M., Peelle, E. B., Wolfe, A. K. & Munro, J.F. (1998). Measuring the success of public participation on environmental restoration and waste management activities in the U.S. Department of Energy. Technology in Society, 20, 385–406.

Civil Society Development Center (CSDC). (2005). First Meeting Report: Local Government and NGOs Cooperation in Participatory Democracy Project. Ankara: CSDC.

Cooke, B. & Kothari, U. (2001). The Case for Participation as Tyranny. In B. Cook & U. Kothari (Eds.), Participation: a New Tyranny? (pp.1-15). London, Newyork: Zed Books.

Cooper, J. (2002). Evaluating Public Participation in the Environmental Assessment of Trade Negotiations. Report for Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade.

Dowling, B., Powell, M. & Glendinning, C. (2004). Conceptualizing successful partnerships. Health and Social Care in the Community, 12(4), 309-317.

Dunn, D. S. (2008). Research Methods for Social Psychology. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publication.

Fung, A. & Wright, E.O. (2003). Thinking about Empowered Participatory Governance. In A. Fung & Wright, E.O. (Eds.), Deepening Democracy (pp.3-42). Newyork, NY: Verso.

Hagmann, J., Chuma, E., Murwira, K. & Connolly, M. (1999). Putting Process into Practice: Operationalizing Participatory Extension, Agren, 94, 1-18.

Healey, P. (1997). Collaborative planning: shaping places in fragmented societies.

Basingstoke, Hampshire, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kulözü, N. (2014). Different Participant Groups, Different Success Definitions: An Exploratory Study in the Case of “Local Government and NGO Cooperation in Participatory Democracy Project”. Boğaziçi Journal, Review of Social, Economic and Administrative Studies 28 (1): 47–67.

Kulözü, N. & Tekeli, İ. (2014). Socio-Psychological Factors Affecting the Participatory Planning Processes At Interactional Level. MEGARON/Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi, Mimarlık Fakültesi E-Dergisi 9: 1–13.

Kulözü, N. (2016). Communication as a Socio-psychological dimension of participatory planning processes: the Cases of the Participatory Processes of Gazi, Kaymaklı, Odunpazarı & Seyrek from Turkey. International Planning Studies, 21(2), 207-223.

McCool, S. F. & Guthrie, K. (2001). Mapping the Dimensions of Successful Public Participation in Messy Natural Resources Management Situations. Society and Natural Resources, 14 (4), 309-323.

Pascaru, M. & Buţiu, C. A. (2010). Psycho-Sociological Barriers to Citizen Participation in Local Governance: The Case of Some Rural Communities in Romania. Local Government Studies, 36 (4), 493-509.

Schulz, A. J., Barbara, A. I. & Lantz, P. (2003). Instrument for evaluating dimensions of social dynamics within community-based participatory research partnerships. Evaluation and Program Planning, 26, 249-262.

State Planning Organization (2004). İlçelerin Sosyo-Ekonomik Gelişmişlik Sıralaması Araştırması. Ankara: Bölgesel Gelişme Ve Yapısal Uyum Genel Müdürlüğü.

Tippett, J., Searle, B., Pahl-Wostl, C. & Rees Y. (2005). Social learning in public participation in river basin management—early findings from HarmoniCOP European case studies. Environmental Science and Policy, 8, 287-299.

Tuler, S. & Krueger, R. (2001). What is Good Public Participation Process? Five Perspectives from the Public. Environmental Management, 27 (3), 435-450.

Wondolleck, J. M. & Yaffee, S.L. (2000). Making Collaboration Work: Lessons from Innovation in Natural Resource Management. Covelo CA: Island Press.

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publishing.

Zucker, L. G. (1987). Institutional Theories of Organization. Annual Review of Sociology, 13, 443-464.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 May 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-009-9

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

10

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-57

Subjects

Politics, government, European Union, European institutions

Cite this article as:

Kulözü, N. (2016). Effects of Interpersonal Relationship Dimension on Locally Specific Participatory Processes. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), Political Science, International Relations and Sociology - ic-PSIRS 2016, vol 10. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 36-49). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.05.03.5