Abstract

Eating disorders affect 5-10 million females, triple the rates of people living with AIDS or schizophrenia. Traditional research acknowledged interconnecting factors in developing anorexia nervosa, yet few studies attempted to examine the meaning of gender and embodiment from the anorexic woman's unique perspective. Thus, this study attempts to describe and illuminate this rift in the literature regarding intertwining regions of gender, embodiment, and the presence of anorexia nervosa. Data were obtained from a mixed-methods approach, with interview reports of subjects' life experiences and the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI). Female participants (N = 6) between 19 and 29 years old were interviewed in conformity with commonly accepted phenomenological data collection procedures. Results show the meaning of gender and embodiment in the experience of being a woman with anorexia is characterized by events that cause a downward spiral into hopelessness, depression, and negative self-esteem. The study identified no correlation between BSRI and the presence of anorexia, but revealed seven themes:

Keywords: Eating disorders, anorexia nervosa, gender role, gender, embodiment

Introduction

The death of singer Karen Carpenter in 1983 focused attention on eating disorders, particularly anorexia nervosa. The dissonance between her stardom and death from anorexia convinced people of the profound seriousness of this disorder. Many theories were discussed about development of her eating disorder, and medical and health care professionals soon began recognizing, regularly diagnosing, and treating eating disorders.

As a cultural phenomenon, an examination of anorexia nervosa must connect with an analysis of the categories of gender and embodiment. Most people diagnosed and hospitalized for anorexia nervosa are female (Brumberg, 1982, 1988; Faludi, 1991; Hoek, 1993), and an important descriptive criterion for the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa is the presence of disturbances in an individual's body perception (DSM-IV, 1994). Thus, examining the interconnecting aspects of gender and embodiment is essential in light of the current incidence of cases of anorexia nervosa.

Almost half the women in the United States are on a diet in any given day, and 80% of women are dissatisfied with their appearance (Smolack & Levine, 1996; Wolf, 1992). By the age of 10 years, 80% of children are afraid of being fat, and almost half of U.S. elementary students between the first and third grades reported wanting to be thinner (Eating Disorder Awareness and Prevention (EDAP), 1999). Eating disorders affect approximately 5 million to 10 million adolescent girls and women (Crowther, Wolf, & Sherwood, 1992), triple the rate of people living with AIDS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1998) or schizophrenia (EDAP, 1999). Women's bodies do indeed, "emit signs" (Foucault, 1979).

The literature in the respective areas of gender, embodiment, and anorexia nervosa includes hundreds of psychological analyses, experimental studies, meta-studies, treatment recommendations, and theoretical formulations. Much clinical literature attempted to link eating disorders with a specific pathogenic condition, such as the psychoanalytic (Breuer & Freud, 1982), depressive (Bliss & Branch, 1960), or perceptual geneses (Bronfen, 1992).

Psychologists, analysts, therapists, physicians, and medical providers historically provided a plethora of rationales for the origin, development, and treatment of anorexia nervosa (Albutt, 1901; Bemporad, 1996; Ferenczi, 1919; Glucksman, 1989; Groddeck, 1929; Ritvo, 1984). Yet, both anorexia and bulimia appear in ever-increasingly diverse populations of women, reducing the possibility of describing a distinctive profile or pinpointing a specific pathogenic condition (Bordo, 1993; Crowther et al., 1992; Snyder & Hasbrouck, 1996).

No quantitative studies have connected the body to the consideration of both gender analysis 23

and anorexia nervosa, and no qualitative studies on anorexia nervosa regarded the bond between the meaning of gender and the body. The focus of this study was therefore to describe and illuminate this rift in the literature regarding the intertwining regions of embodiment, gender, and the presence of anorexia nervosa.

1.1 Definition of Anorexia Nervosa

In this study, the terms and are defined per the American Psychiatric Association (DSM-V, 2013). The descriptive criteria for anorexia nervosa comprises a refusal to maintain a minimally normal body weight, intense fear of gaining weight, and significant disturbance in the perception of the body's shape or size. Anorectics can also be amenorrheaic due to abnormally low estrogen levels that are, in turn, due to diminished pituitary secretion of folliclestimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone.

Anorectics can be of the restricting type, characterized by food intake restriction through fasting, dieting, or excessive exercise, or of the binge-eating/purging type, exemplified by regular binge eating, then purging through self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas (DSM-V, 2013). This study made no participant restriction between restricting- and binge/purge- types of anorexia.

1.2 Definitions of Gender and Embodiment

The term is used to broadly outline an analytic category traditionally referring to the study of sex, sex roles, gender, gender roles, gender bias, gender role identity, gender expectations, gender role attitudes, sexism, femininity, masculinity, androcentrism, and language use (Gergen & Davis, 1997). The term is used to refer to body image, body image expectations, biological sex, one's experience of being in one's body, and one's relationship to one's body (Allen, 1982; de Beauvoir, 1974; Bordo, 1993; Irigaray, 1985a, 1985b; Merleau-Ponty, 1962, 1968).

1.3 Qualitative Methodology

A qualitative methodology was chosen due to the zones upon which this study is primarily focused: meaning exploration and human life-theme analysis. Whereas quantitative methodology best serves to measure and quantify phenomenon, this study sought to illuminate and uncover meanings and themes in psychological exploration (Giorgi, 1985). Further, the traditional empirical approach to psychological research could disrupt the contextualized nature of subjects' lives (Bordo, 1993).

Generally, traditional experimental approaches in the human sciences do not capture life as it is lived, but idealistically take the subjects out of their lives to control or manipulate significant variables. However, the inherently contextual approach is the very essence of various qualitative methods, such as the phenomenological, feminist, intersubjective, and grounded theoretical approaches (Daly, 1978, 1984; Denzin & Lincoln, 1998; Eichenbaum & Orbach, 1983; Guba, 1981, 1990; Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Luepnitz, 1988; Strauss & Corbin, 1990).

Accordingly, I chose a phenomenological research methodology for the interview and analysis of verbatim transcripts. Phenomenology has a long and respected tradition within the discipline of philosophy and other social sciences, but has been largely ignored by mainstream psychology. I followed phenomenological research methodology as elucidated by Giorgi (1970,

1971a, 1971b, 1975, 1983, 1985, 1994, 2000), philosophically originated by Husserl (1931, 1960, 1982), and psychologically informed by Merleau-Ponty (1962, 1968).

I chose this methodology because it honors the phenomenological tradition of Husserl and is especially focused in the Merleau-Ponty tradition concerned with the interwoven, inherently contextual, language-oriented, and embodied nature of human meanings. Giorgi's phenomenological psychology research method was chosen for its ability to scrutinize psychological data through his rigorous analytic method.

1.4 Summary Remarks

The broad intention of the study was to illuminate, expose, and fill the literature gap especially pertinent to anorectics' self-understanding of the factors contributing to the development of their eating disorder. It was my intent to elucidate the framework of the life meaning of these three important intertwining aspects for women—anorexia nervosa, gender, and embodiment—rather than focus on effective therapies or new clinical treatments for anorexia. The concentration, therefore, is examination of the lived meaning of gender and embodiment, to illuminate the experience of women with anorexia nervosa. It was also hoped the results would assist clinicians to identify the unique themes and meanings anorexic women face within their lives, the diagnostic arena, and the medical and psychotherapeutic treatment realms.

Methodology

To understand the lived meaning of gender and embodiment in women with anorexia nervosa, I conducted interviews with six female volunteer participants using generally accepted phenomenological psychotherapeutic interview and phenomenological psychology research methods, a semistructured interview format, a simple demographic questionnaire, and standardized administration of the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI). This approach would generally be considered a mixed-methods approach.

The open data collection phase was completed October 2001. All participants were screened volunteers who responded to an advertisement, previously diagnosed by mental health professionals as anorexic, and formerly or currently in treatment for their anorexia nervosa. The presence of anorexia nervosa was assumed; the focus of the study questions was instead on gender and embodiment's contributions to anorexia nervosa.

2.1 Phenomenological Psychotherapeutic Interview Method

Within this orientation, I adopted Smith's (1979) phenomenological psychotherapeutic

framework for interviewing:

- Bracketing or suspending the natural attitude, including any previous hypothesis.

- Attending closely to how I co-constituted the interview session.

- Attending to my own cultural values and assumptions, and how they shape the

- interview session.

- Instead of testing hypotheses through measurement and laboratory situations, I based

- my interpretations on interview session descriptions and reflections.

As such, the interviews were open ended and incorporated questions emerging from the

interview discussion as well as the interview protocol. Audiotapes of interview sessions were

transcribed verbatim, including my questions and participants' responses, with the interview protocol questions numbered accordingly, and the transcripts analyzed using phenomenological psychology research methodology.

2.2 Phenomenological Psychology Research Method Rationale

Radically breaking with philosophical tradition, Husserl (1931, 1960, 1982) defined phenomenology as the study of "the manifest," or "that which shows itself." Within this framework, the perceiver has unmediated and direct access to the phenomenon. Husserl held that the problem with philosophy and the science of psychology was their epistemological attempts to ground the general and universal laws of logic based on an empirical psychological investigation of "thinking." For Husserl, one cannot think without or presupposing that which our senses tell us is really real. For example, I cannot take a step without assuming that the floor is really present. I presuppose that because I perceive the floor's presence, I can safely take that step. refers to the phenomenological process by which I assume the phenomenon perceived has a reality separate from my perception of it.

This process is termed the, whereby phenomenological suspension leads to phenomenological reduction and bracketing or suspension. Husserl defined the investigation of the underlying condition or cause of thinking as the or and called the entire process. Husserl (1931, 1960, 1982) saw the process of thinking as inseparable from fact and defined the subject as "being in the world" and the constitutive source for all worldly meaning ().

Essential in an exploration of phenomenological psychological research from Merleau-Ponty's (1962, 1968) theoretical framework is a discussion of the intertwining of perception, language, and the body. Merleau-Ponty saw language as "sedimented" within the body, and any attempts to discuss language as leading to perception and the body. Merleau-Ponty, Bordo (1993), and Butler (1990, 1993) and considered the body as always already in the world; therefore, there is no dualism or body-in-itself that could be objectified or given universal status.

Perception, then, is always an embodied perception; and it exists only within a specific context or situation. Perception-in-itself does not exist. The phenomenological researcher's task, therefore, is to foster and embrace the rebirth from a connected or intertwined perspective, similar this framework, the to intersubjective and feminist theoretical approaches. Within phenomenological researcher must be open to others' lived experiences or risk what Merleau-Ponty (1968) called thethat which seeks to hold and capture, rather than allowing being the space to truly, wholly. The bad dialectic seeks to ignore significations that surround a term, and wishes only to hold the term to its "proper" definition.

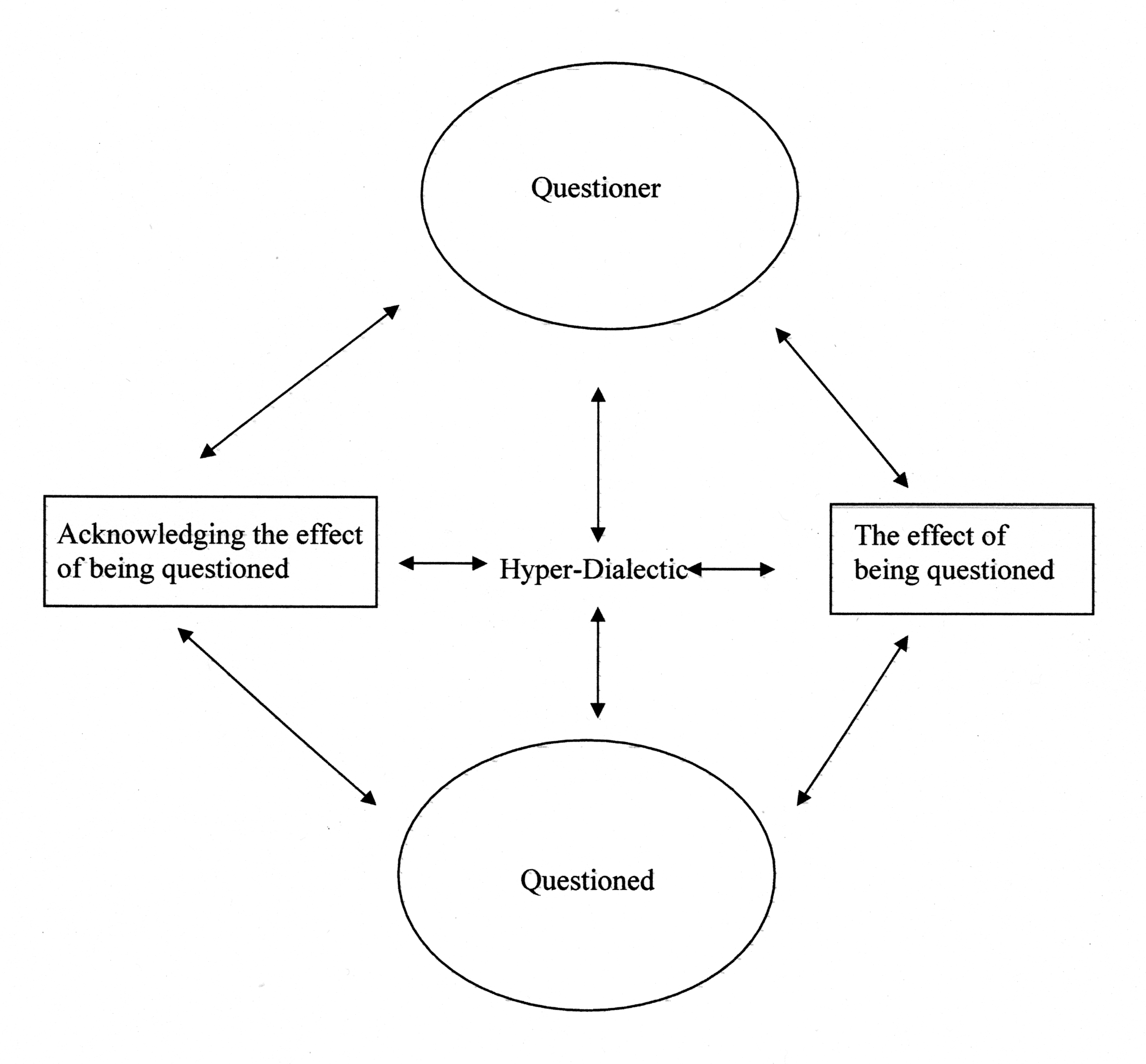

Phenomenological researchers must acknowledge and weigh their words, perceptions, and bodily expressions carefully to not dominate the research interview. Tension between asserting the self and recognizing the other is compatible with Merleau-Ponty's (1968) notion of the good or. The hyperdialectic takes into account its own effect on the language being spoken, the questions being asked, the very desire to ask particular questions, and the effect that questioning has on the questioned. The reality of the research framework from a phenomenological perspective is one within which the researcher and the participant co-create their experience, and are mutually interactive (Figure 1).

To ignore the tension of asserting the self and recognizing the other—and therefore to dominate the interview session—employs the bad dialectic with far-reaching implications. Researchers who dominate interviews by asserting the absolute correctness of their own perceptions are employing the bad dialectic. They effectively rules out the participants' experiences (Benjamin, 1990). For Merleau-Ponty, our true being in language is in dialogue, and the hyperdialectic is essential to the full openness of being. A wholly open research encounter is open to dialogue and a challenging of ideas.

2.3 Use of Researcher as Instrument

Inherent in the above approach is the researcher's perceptions as an essential facet of the research study (Harding, 1986, 1987a, 1987b, 1991). An intricate balance must be maintained between the context of the participant's and the researcher's perceptions to maintain the hyperdialectical space to accurately report and analyze research results. Researchers must be open to a challenging of ideas and aware of their own perceptions, use these perceptions as essential

data, and analyze them as part of the study.

2.4 Participant Selection

Participants were obtained by through advertisements in various northwestern United states urban university newspapers, the State Psychologist Newsletter, faxes to area psychologists working with eating disordered women, and by email to area treatment providers specializing in eating disorders;

Participants were screened volunteers who were European American (White/Caucasian), female, at least 18 years of age; English speaking, and had previously completed or were currently in treatment for anorexia. All participants had previously been formally diagnosed with anorexia nervosa by mental health professionals.

2.5 Data Collection

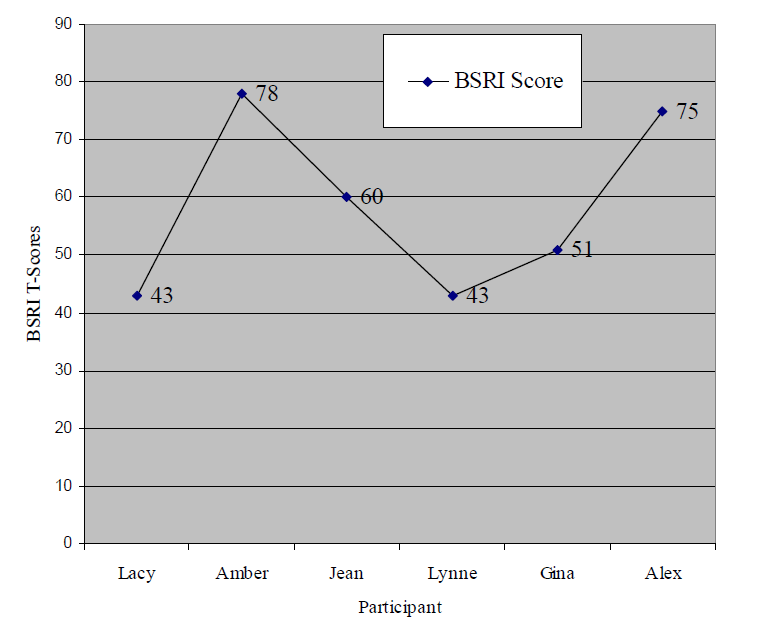

Participants completed the BSRI (Bem, 1974, 1981), which was scored in standard procedure

and tabulated in comparison with other participants' scores and with the participant's self-identified gender role (Figure 2). The BSRI, which consists of 60 self-descriptive, personality-characteristic adjectives, was chosen because it is designed to measure psychological masculinity and femininity as two independent variables, and has held up to studies examining validity (Gadreau, 1977; Holt, 1998).

femininity and masculinity scales (Bem, 1981).

All adjectives are designed to be positively toned or socially desirable. Twenty items each assess masculinity, femininity, or neutral. Each adjective is ranked on a scale of 1 to 7, where 1 = and 7 =. Individuals can be classified

based on median splits as masculine (high masculinity, low femininity), feminine (high femininity, low masculinity), androgynous (high masculinity, high femininity), or undifferentiated (low masculinity, low femininity).

Audiotaping was used to record the interviews, which followed a semistructured interview protocol with additional open-ended prompting questions to encourage rapport and disclosure. Two questions were added: an initial request to explain the history of the participant's anorexia and a closing question asking if there were anything the participant would like to add.

2.6 Data Analysis

Within the phenomenological psychology research methodology, the following general

phenomenological strictures were followed:

Description. The phenomena to be studied must be described precisely as they present

themselves.

Reduction. Because the description takes place within the attitude of the phenomenological reduction, the researcher (a) brackets or disengages from all past theories or knowledge about the phenomenon, and (b) withholds existential assent of the phenomenon.

Search for Essences. After the description is obtained within reduction, the researcher begins free imaginative variation, whereby aspects of the concrete phenomenon are varied until its essential characteristics show themselves. The researcher then describes the invariant characteristics and their relationship to each other, which become the structure of the phenomenon (Husserl, 1931, 1960).

Thus, I read each participant's interview transcript as many times as necessary to obtain a sense of the whole and continued this phase until saturation with the information contained within the individual transcript. Once I grasped the sense of the whole, I read the text several times again to obtain natural meaning units from a psychological perspective and focus on the phenomena researched, especially the most revelatory units.

Finally, I synthesized all transformed meaning units into a consistent statement regarding the participant's experience: the structure of the experience, which generated answers and identified emergent themes, patterns, and future research questions.

2.7 Data Validation

To deal with major threats to the study—specifically, my own and participants' historical and cultural hypotheses and biases, qualitative methodology bias, and participant self-selection and selfreport biases, the findings were validated through coded case-by-case analysis, enabling more accurate data analysis. Cross-case analysis and analysis of negative evidence were used to discover intersections and divergences in participants' transcripts. Another validity check used an additional coder for approximately 16% of randomly selected transcripts (Guba, 1981; Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Disagreements were resolved by discussion, with reference to the phenomenological methodology and participant's words.

The BSRI was administered in standard fashion to quantitatively categorize the gender roles to which each participant ascribed, and was triangulated with the interview responses (Bem, 1974, 1981). The analyzed data was provided to the participants for an additional verification (Streigel-Moore, 1994).

Results

The following descriptions show the resultant natural meaning units as the transfers took place within the individual descriptions of experience (Giorgi, 1970, 1971a, 1971b, 1975, 1983, 1985, 1994, 2000). Table 1 displays participant demographics.

To make the "essential psychological significance explicit" (Barrell, Aanstoos, Richards, & Arons, 1987), a single general structure of the integrated essential insights found in the individual descriptions is presented. This general structure shows the essential meaning of the phenomena of gender and embodiment in women with anorexia and describes the recurring themes and categories of this experience (Table 2).

Experiencing the development of anorexia takes the form of feeling "not good enough" because of direct comments from authoritative others about the participant's body or need to lose weight, and feeling depressed about a situation that the participant felt was hopeless. Comments from authoritative others were powerful messages for the participants that lead to negative thoughts about self. Participants expressed feelings of being "less than…" Their development of a female body at puberty were difficult transitions, marked first by awareness of their own body and then painful awareness of other's negative perceptions of their changing body.

Participants strived for a perfect, ideal female body; their self-image depended on their perceptions of their external appearance and how closely it matched the ideal portrayed in their own minds, as derived from the media or from the perceived male ideal. The body was experienced as a separate, controllable thing that might be peeled off to provide a different, better life if it were changed or traded in for a new one.

Although the study did not find anorexic behavior to directly correlate with feminine gender-role orientation, participants experienced traditional feminine gender-role characteristics as negative, limiting, and devalued in society. Being a woman carried little positive connotation, and the anorexic's concern with appearance was described as a negative feminine gender-role characteristic. However, participants experienced characteristics described as masculine—such as strength and control—as neutral or positive, and desirable.

Participants experienced the role of anorexia as a powerful part of their lives. Establishing control over eating was sometimes the only control they felt they could exercise. Each tended to feel inability to change her behavior, and then despair and hopelessness when she recognized that she had lost control.

Experiencing loss of control was the precipitating factor in the participants' acknowledgment that there was a problem and seeking help. Although participants experienced long-term physical health problems because of anorexia, maintaining anorexic behavior was all encompassing—becoming more important than anything else in their lives. They dropped all other social activities that interfered with the anorexic behavior. They equated good external physical appearance with good self-esteem, and their thoughts of having a new body represented thoughts of having a new self.

The experience of initiating intervention (inpatient or outpatient) was characterized by acknowledging loss of control, parents and others expressing concerns or ultimatums, and eventually by gaining information about the importance of nutrition, healthy eating, and exercise.

Participants changed their perceptions and hopes for a new life following by gaining information about anorexia and realizing that anorexic behavior was only one of many possible coping devices. Participants experienced a changed, more positive perception of their own bodies, the female body, and the feminine gender role, and more positive eating, thinking, and behaving patterns.

Table 3 presents quotations from participant interviews that exemplify the emerging themes.

Discussion

The meaning of gender and embodiment in the experience of being a woman with anorexia is characterized by a number of events that cause a downward spiral into hopelessness, depression, and negative self-esteem. For example, five of six (83%) participants reported a significant exchange with someone important in their lives.

4.1 Theme 1: Importance of Others' Perceptions

The initial thematic finding of the importance of others' perceptions—specifically, that a comment from a person in authority may provoke anorexic-type behavior—was consistent across the literature (Bliss & Branch, 1960; Bordo, 1993; Bruch, 1973, 1979; Hoek, 1993; Hsu, 1990), in part because of the authoritative person's attitude toward the age and gender of the person being addressed, perceptions of the ideal feminine body, age, and gender (Brier & Lanktree, 1983; Bem & Bem, 1973; Cronin & Jreisat, 1995; Edwards, 1998; MacKay, 1980).

Additionally, each participant experienced confusing, contradictory messages from important others regarding dieting and weight loss. Coupled with the participant's observations of others' perceptions of their own body, they experienced the mixed messages as contributing to negative self-esteem.

4.2 Theme 2: Negative Self-Esteem

The double standard produced by confusing messages from others, coupled with the comment from the authoritative person about the need to lose weight, set up production of negative selfesteem. All participants expressed feeling negative self-esteem and directly related this to developing their eating disorder—consistent with the literature (Luepnitz, 1988; Rutherford & Russell, 1990; Wolf, 1992). Further, all experienced a difficult transition into womanhood, initially characterized by unself-consciousness and lack of awareness of their own bodies. At prepubescence, the participants did not experience their bodies as a separate thing.

4.3 Theme 3: Perceptions of the Feminine Body

Each participant experienced awareness of her body negatively, and attributed the body as the site and condition of all negative events that transpired (Wolf, 1992). This changed awareness of the developing feminine body was especially difficult because of the message recipient's age. For example, Lacy was 13 years old when her coach told her to lose weight, and she experienced the situation as very damaging to her self-esteem. She perceived the other's negative comments and perceived negative perceptions of her developing feminine body as total rejection and, in turn, experienced negative self-esteem and negative, limited perspectives of the feminine body.

Each participant experienced the influence of the media—television, advertising, and fashion magazines—as directly influencing perceptions of the feminine body, consistent with the literature (Luepnitz, 1988; Murnen & Smolak, 1997; Snyder & Hasbrouck, 1996; Streigel-Moore, 1994; Wolf, 1992). All participants emphasized external appearance and equated a good external appearance with feeling good about self. Amber (p. 1) related, "I didn't care about wanting to get better, only…to be better, look better." Because others' attention focused on the external feminine body, participants were also drawn

to the external body. They subjugated concern about other characteristics of the woman to an overwhelming focus on appearance. For example, Gina experienced increased self-esteem when she felt her body looked good and approached her internalized ideal body weight.

In essence, through becoming aware of others actively objectifying their developing feminine bodies, participants began to objectify their own bodies, internalizing cultural expectations for the feminine body.

Media present the ideal woman as flawless (Bordo, 1982; Butler, 1990, 1993; Daly, 1978, 1984; Wolf, 1992). Women on television and in print have no physical flaws. The participants, like all women, had been exposed to these societal demands and succumbed to these ideals. They measured success and self-esteem by externally comparing their bodies with their internalized image.

In adopting cultural expectations—taking a critical perspective and treating the feminine body as an object—the anorexic woman can be "caught up in a power situation of which they are themselves the bearers" (Foucault, 1979) and actively produce the feminine body as an object to herself (Allen, 1982; Benjamin, 1990; Bordo, 1993; Bronfen, 1992; Faludi, 1991; Irigaray, 1985b; Wolf, 1992).

4.4 Theme 4: Perceptions of the Feminine Role

The anorexic woman's perceptions of the feminine body intertwine with perceptions of the feminine role. Though only half the participants evidenced a feminine gender-role orientation (three oriented toward the masculine gender role, with one of them approaching androgyny), all participants experienced the traditional feminine gender role as negative, limiting, and devalued in society. (Figure 2 shows participants' proportion of femininity/masculinity.)

obtained by calculating individual responses to provide a raw score (RS), and translating the RS

into a standard score (SS) based on a standardized sample (Bem, 1981)

This finding was both consistent and contrary to the literature (Crowther et al., 1992; Flannery-Schroeder & Chrisler, 1996; Hsu, 1990; Smolak & Levine, 1996; Snyder & Hasbrouck, 1996), depending upon the study. For example, Alex (feminine gender-role orientation) experienced negative role perceptions and drastic limitations in what she wanted to do because of her concern with meeting the feminine role.

Not attending to feminine role characteristics was experienced as hazarding the loss of those characteristics. Lynne (masculine gender-role orientation) connected her negative perceptions of the limitations and the devaluing of the feminine role to her experiences of her mother.

With cultural and historical devaluation of the feminine gender role, all participants elevated and prioritized masculine characteristics as desirable (Allen, 1982; Benjamin, 1990; Bordo, 1993; Bronfen, 1992; Faludi, 1991; Irigaray, 1985b; Wolf, 1992). For example, Gina (masculine gender role orientation approaching androgyny) experienced the feminine gender role as limiting, and it made her angry. In Gina's concern with "proving them wrong," she experienced the need to prioritize characteristics considered masculine and to de-emphasize characteristics considered feminine. All the women in the study elevated masculine gender role characteristics, such as being strong and in control.

4.5 Theme5: Role of Anorexia in Woman's Life

Participants characterized the role of anorexia in their lives in a variety of important facets: control, loss of control, comfort, something of one's own, obsession, compulsion, a companion, a cause of physical problems. For the participants, the role of anorexia functioned similar to that related in the literature (Bliss & Branch, 1960; Bordo, 1993; Bronfen, 1992; Bruch, 1979; Brumberg, 1988; Butler, 1993; Faludi, 1991; Flannery-Schroeder & Chrisler, 1996; Hoek, 1993; Hsu, 1990).

Alex, for example, characterized her anorexia as an occupation she had control over. Her description of her disease sounded like a friend who helped her fill free time. Control played a major role in all participants' experiences of anorexia, consistent with the literature (Bliss & Branch, 1960; Bordo, 1993; Bronfen, 1992). As Lacy stated, "I just did what I could…it was so important to me then, it was the most important thing in my life" (Lacy, p. 3).

Given the all-important role anorexia played in the participants' lives, intervention and obtaining treatment were difficult prospects, but each participant shared this study criterion.

4.6 Theme 6: Importance of Intervention and Gaining Information about Anorexia

Whether the participants' parents or significant other initiated the intervention, all participants' turning point was realizing they had lost control of the disease. An involvement initiated by significant others was required to convince all participants of the importance of intervention and gaining information about anorexia.

All participants related that gaining information about anorexia was very important in their initial intervention and continued recovery. As they internalized information gained in treatment and applied it in their lives, they began to change their perceptions and hopes for a new life.

4.7 Theme 7: Changed Perceptions and Hopes for a New Life

Changed perceptions and hopes for a new life were characterized by the realization that anorexic behavior was only one of many available coping devices. With this awareness, participants experienced changed perceptions of the feminine role and the female body, consistent with the literature (Allen, 1982; Benjamin, 1990; Bronfen, 1992; Bordo, 1993; Faludi, 1991; Irigaray, 1985b; Wolf, 1992). Further, this revaluing allowed all participants to experience changed eating, thinking, and behaving patterns that resulted in hopes for a new life.

4.8 Researcher's Experiential Data

Throughout this study, I reciprocally used my own perceptions and impressions to provide invaluable data within the feminist and phenomenological research methodologies. The struggle in contextual studies is acknowledging the tension between solipsism and the scholarly presentation of a relevant study. The difficulty also is in the dearth of scholarly, mainstream models for presenting research results that take into account researchers' experiential data (Merrick, 1999; Porter, 1999).

Taking the student rather than "objective researcher" stance in my questioning appeared to resolve some of the "subject problem." I was aware that my also being a woman inevitably influenced the results and my experience of the study. In analyzing the first transcripts, I struggled with letting the participant's words speak, rather than clinically interpreting the data. As I continued to meet with participants, I realized I had interpreted their behavior through my own perception, although participants described their experiences differently. I was reminded of the importance of being mindful of the perils of solipsistic definition.

Remaining within the hyperdialectic zone (Figure 1) in this study was a process of remaining aware of the tension between solipsism and complete objectification, as well the effect my presence had on the study data and the data's effect on me. For example, with a few of the study participants, I experienced a very powerful urge to eat following the interviews. Having an anorexic friend, I recognized this feeling as a helpless, misplaced nurturing desire in response to my friend's food restriction—but only when my friend was having particular difficulties.

In light of the study participants, I used this "subjective" feeling to gage the distress level being experienced by the participants—essential data in light of the study topic. Had I not had this previous experience, been exposed to the same cultural influences as the participants were, or paid attention to this feeling, I would have missed rich contextual data.

4.9 Study Limitations

Data on late-onset anorexia characteristics might have yielded a different perspective in comparing challenges women face at different ages. Also, all participants in this study were European American; women from different ethnic groups may have experienced the meaning of embodiment and gender differently because of cultural differences.

4.10 Suggestions for Further Research

Future research could aid understanding by comparing gender role and embodiment study results with characteristics of women who are not anorexic, of different education levels, of homosexuals, or of a male population.

Comparing personality characteristics evidenced by anorexic women who successfully recover with women who do not recover would be essential in light of anorexia's mortality rate.

Understanding different levels of effective coping and what characteristics account for variability would help define resiliency factors for women with anorexia and in general.

References

Albutt, T. C. (1901). Chlorosis. In T. C. Albutt, A system of medicine by many authors (pp. 481- 518). New York, NY: Macmillan.

Allen, J. (1982). Through the wild region: An essay in phenomenological feminism. Review of Existential Psychology and Psychiatry, 18(1-3), 241-256.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Barrell, J., Aanstoos, C., Richards, A., & Arons, M. (1987). Human science research method. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 27, 424-457.

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 155-162.

Bem, S. L. (1981). Bem sex role inventory: Professional manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Bem, S. L., & Bem, D. J. (1973). Does sex biased job advertising "aid and abet" sex discrimination? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 3(1), 6-18.

Bemporad, J. R. (1996). Self starvation through the ages. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 19, 217-237.

Benjamin, J. (1990). The bonds of love: Psychoanalysis, feminism, and the problem of domination. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Bliss, E. L., & Branch, C. H. (1960). Anorexia nervosa: Its history, psychology and biology. New York, NY: Hoeber.

Bordo, S. (1993). Unbearable weight. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Breuer, J., & Freud, S. (1982). Studies on hysteria. New York, NY: Penguin. (Original work published 1893-1895).

Brier, J., & Lanktree, C. (1983). Sex role related effects of sex-bias in language. Sex Roles, 9(5), 625-632.

Bronfen, E. (1992). Over her dead body: Death, femininity and the aesthetic. Manchester, MA: Manchester University Press.

Bruch, H. (1973). Eating disorders: Obesity, anorexia nervosa, and the person within. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Bruch, H. (1979). The golden cage: The enigma of anorexia nervosa. New York, NY: Vintage.

Brumberg, J. (1982). Chlorotic girls: 1870-1920: A historical perspective on female adolescence. Child Development, 53. 1468-1477.

Brumberg, J. (1988). Fasting girls: The emergence of anorexia nervosa as a modern disease. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Burke, J. P., & van der Veken, J. (Eds.). (1993). Merleau-Ponty in contemporary perspective.Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York, NY: Routledge.

Butler, J. (1993). Bodies that matter: On the discursive limits of "sex." New York, NY: Routledge. Cronin, C., & Jreisat, S. (1995). Effects of modeling on the use of nonsexist language among high school freshpersons and seniors. Sex Roles, 33, 819-830.

Crowther, J. H., Wolf, E. M., & Sherwood, N. E. (1992). Epidemiology of bulimia nervosa. In J. H.

Crowther & D. L. Tennenbaum (Eds.), The etiology of bulimia nervosa: The individual and familial context. Washington, DC: Hemisphere Publishing Corporation.

Daly, M. (1978). Gyn/Ecology: The metaethics of radical feminism. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Daly, M. (1984). Pure lust: Elemental feminist philosophy. London, United Kingdom: Women's Press.

de Beauvoir, S. (1974). The second sex. New York, NY: Vintage.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (1998). The landscape of qualitative research: Theories and issues. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Eating Disorders Awareness and Prevention (EDAP). (1999). Statistics in context. Retrieved from http://www.edap.org/edinfo/stats.html Eichenbaum, L., & Orbach, S. (1983). Understanding women: A feminist psychoanalytic approach.New York, NY: Basic Books.

Edwards, R. (1998). The effects of gender, gender role, and values on the interpretation of messages. In Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 7(1), 52-71.

Eschholz, P., Rosa, A., & Clark, V. (1986). Language awareness. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press.

Faludi, S. (1991). Backlash: The undeclared war against American women. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Ferenczi, S. (1919). The phenomenon of hysterical materialization. Thoughts on the conception of hysterical conversion and symbolism. In Further contributions to the theory and technique of psycho-analysis. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Flannery-Schroeder, E. C., & Chrisler, J. C. (1996). Body esteem, eating attitudes, and gender-role orientation in three age groups of children. Current Psychology: Developmental, Learning, Personality, Social, 15(3), 35-248.

Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. (A. M. Sheridan, Trans.). New York, NY: Vintage/Random House.

Gaudreau, P. (1977). Factor analysis of the Bem sex-role inventory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 45. 299-302.

Gergen, M., & Davis, S. (Eds.). (1997). Towards a new psychology of gender. New York, NY: Routledge.

Giorgi, A. (1970). Psychology as a human science: A phenomenologically based approach. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Giorgi, A. (1971a). A phenomenological approach to the problem of meaning and serial learning.

In A. Giorgi, W. F. Fischer, & R. von Eckartsberg (Eds.), Duquesne studies in phenomenological psychology, Vol. I. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Giorgi, A. (1971b). Phenomenology and experimental psychology: In A. Giorgi, W. F. Fischer, & R. von Eckartsberg (Eds.), Duquesne studies in phenomenological psychology, Vols. I-II. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Giorgi, A. (1975). An application of phenomenological method in psychology. In A. Giorgi, C. Fischer, & E. Murray (Eds.), Duquesne studies in phenomenological psychology, Vol. II. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Giorgi, A. (1983). Concerning the possibility of phenomenological psychological research. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 14(2), 129-169.

Giorgi, A. (1985). Phenomenology and psychological research. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Giorgi, A. (1994). A phenomenological perspective on certain qualitative research methods. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 25(2), 190-220.

Giorgi, A. (2000). The status of Husserlian phenomenology in caring research. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 14, 3-10.

Glucksman, M. (1989). Obesity: A psychoanalytic challenge. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, 17, 151-171.

Groddeck, G. (1929). The unknown self: A new psychological approach to the problems of life with special reference to disease. New York, NY: C.W. Daniel.

Guba, E. G. (1981). Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiry. Educational and Technology Journal, 29, 75-92.

Guba, E. G. (1990). The paradigm dialog. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Harding, S. (1986). The science question in feminism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Harding, S. (Ed.). (1987a). Feminism and methodology: Social sciences issues. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Harding, S. (1987b). Is there a feminist method? Hypatia, 2, 17-32.

Harding, S. (1991). Whose science? Whose knowledge? Thinking from women's lives. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Hoek, H. W. (1993). Review of the epidemiological studies of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 5(1), 61-74.

Holt, C. (1998) Assessing the current validity of the Bem sex-role inventory. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 39, 929-941.

Hsu, G. L. K. (1990). Eating disorders. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Husserl, E. (1931). Ideas: General introduction to pure phenomenology. New York, NY: McMillan.

Husserl, E. (1960). Cartesian meditations: An introduction to phenomenology. The Hague, Netherlands: Nijhoff.

Husserl, E. (1982). Ideas pertaining to a pure phenomenology and to phenomenological philosophy. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Irigaray, L. (1985a). Speculum of the other woman. (G. C. Gill, Trans.). New York, NY: Cornell University Press.

Irigaray, L. (1985b). This sex which is not one. (C. Porter, Trans.). New York, NY: Cornell University Press.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G., (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. Luepnitz, D. (1988). The family interpreted: Feminist theory in clinical practice. New York, NY: Basic Books.

MacKay, D. G. (1980). Psychology, prescriptive grammar, and the pronoun problem. American Psychologist,35(5), 444-449.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception. (C. Smith, Trans.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968). The visible and the invisible. (A. Lingis, Trans.). Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Merrick, E. (1999). Like chewing gravel: On the experience of analyzing qualitative research findings using a feminist epistemology. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23, 47-57.

Murnen, S. K & Smolak, L. (1997). Femininity, masculinity, and disordered eating: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 22(3), 231-242.

Porter, N. (1999). Reconstructing mountains from gravel: Remembering context in feminist research. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23, 59-64.

Ritvo, S. (1984). The image and uses of the body in psychic conflict: With special reference to eating disorders in adolescence. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 39, 449-469.

Rutherford, J., & Russell, G. F. M. (1990). Anorexia and baby gazing. British Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 898-901.

Savage, G. (1884). Insanity and allied neurosis. Philadelphia, PA: Henry C. Lea.

Smith, D. L. (1979). Phenomenological psychotherapy: A why and a how. In A. Giorgi, R.

Knowles, & D. L. Smith (Eds.), Duquesne studies in phenomenological psychology, Vol. III. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Smolak, L., & Levine, M. P. (Eds.). (1996). The developmental psychopathology of eating disorders: Implications for research, prevention, and treatment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Snyder, R., & Hasbrouck, L. (1996). Feminist identity, gender traits, and symptoms of disturbed eating among college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20(4), 593-598.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Streigel-Moore, R. H. (1994). A feminist agenda for psychological research on eating disorders. In P. Fallon, M. A. Katzman, & S. C. Wolley, Feminist perspectives on eating disorders. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (1998). HIV/AIDS surveillance report.

Wolf, N. (1992) The beauty myth. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

09 July 2015

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-004-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

5

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-88

Subjects

Health, psychology, health psychology,health systems, health services, social issues, teenager, children's health, teenager health

Cite this article as:

Clay, D. L. (2015). The Phenomenology of Anorexia Nervosa: The Intertwining Meaning of Gender and Embodiment. In Z. Bekirogullari, & M. Y. Minas (Eds.), Health and Health Psychology - icH&Hpsy 2015, vol 5. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 22-41). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2015.07.4