Abstract

The advantages of outreach have been widely documented, however little research has been done about educator’s profile in sex work setting. This paper has two major purposes: 1) to identify the characteristics of the outreach worker; 2) to understand the role of training and continuous education in this context. This study has adopted a descriptive and analytic qualitative methodology. Semi-structured interviewswere conducted with 6 members of an outreach team that provide services for street-based female prostitutes, in the city of Coimbra, Portugal. Data was analyzed regarding their level of experience. We concluded that outreach teams might be considered communities of practitioners; and the outreach worker is a reflective educator in streetbased sex work setting, with two types of skills: social and personal; theoretical and practical. Additionally, a profile and a professional identity definitions are required as well as more training and continuous education.

Keywords: Educator’s Skills;,Sex Work, Training

Introduction

Community-based outreach intervention models are associated with an epidemiological tradition, and focus mainly on blood borne infections. Outreach models were developed in the United States (USA) and Europe before the advent of AIDS, and introduced in the USA in the 60s as a response to heroin users (Needle et al., 2005). Outreach encountered successive changes and adaptations, and nowadays it is mostly associated with harm reduction among hard-to-reach populations, including intravenous drug users, homeless and sex workers.

Outreach has an educative and informative role (Rhodes, 1996). It tends to encourage behavior change, through provision of material, such as syringes, needles and condoms; and by dismantling barriers with health and social services. It helps people to gain access to services and treatment, promote voluntary and confidential HIV testing, and counseling (National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), 2002; Needle et al., 2005; Rhodes, 1996). In addition, outreach is also considered a tool for gathering information and knowledge about the population, ways of living, needs and perceptions, giving voice to its clients (Mikkonen, Kauppinen, Houvinen, & Aalto, 2007; Porter & Bonilla, 2010; Whowell, 2010).

Outreach in sex work context was first used in the 80s, focused on safe sex and HIV prevention, and today offers a variety of services in addition to those related with health care (Whowell, 2010). Outreach aims are the following: a) to establish contact with people involved in sex work, who might be an hidden population, due to stigma, criminalization and fear of judgmental attitudes; b) to establish relationships, which could ensure reference and access to formal services, c) to provide harm reduction, information, health and other services; and d) to identify potential sexual exploitation situations (UK Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP), 2008). Regarding to migrant population, Mikkonen et al. (2007) suggest that outreach should also provide information on legal issues, encourage and support the development of confidence and self-esteem; and inform politicians and legislators about the situation of migrants. To implement the outreach strategy, UK Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP, 2008) and TAMPEP (2009) recommend a professional competence-based approach (e.g. respect for human rights, opinions and options; non-interference; establishment of a trustful, empathic and non-judgmental relationship; confidentiality; adaptation to diversity and specificity, taking into account the needs of sex workers); cooperation and coordination with formal services; education and training of outreach staff, and supervision; safety instructions; guidelines to deal with complex situations (e.g. children and people in coerced prostitution, violence); insurance of an holistic intervention that aim to empower and encourage sex workers’ participation (Mikkonen et al., 2007; TAMPEP, 2009; UK Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP), 2008). In this sense, outreach is not only a method but also a personal attitude (Mikkonen et al., 2007). For that reason, according to Mikkonen et al. (2007), the outreach worker must have some personality qualities (e.g. tolerant, confidant, courageous, tough, sensitive, non-judgmental, open minded) to establish a relationship with others (Rogers, 1985), as well as should acquire competence, knowledge (analyses, understand, report), and know-how (practical and theoretical knowledge, communication and cooperation skills).

Competence can be understood as the ability to operationalize a set of knowledge, attitudes and skills in a complex and unique situation, in order to give an effective response (Perrenoud, 1996); or as a combination (not a sum) of resources that a professional mobilizes and takes place in action (Le Boterf, 2003). According to Le Boterf (2003), resources can be personal and environmental, including knowledge (theoretical, professional context, procedures); know-how (formal, empirical, relational, cognitive); skills or qualities; emotional and physiological resources. A competent professional is a person who knows how to manage a complex situation, so it is expected that he/she knows how to act and react with relevance; combine resources and mobilize them in a specific context; transposed to other situations; learn and learning to learn; and become emotionally involved.

In sex work scene, as in others real-world scenarios, situations are rarely straightforward and clear. Outreach workers face complex socio-educational issues, so they must be prepared to deal with situations of uncertainty, instability, uniqueness and value conflict. Since there are no magical formulas, in fact, to deal competently with those matters, improvisation, invention and strategies testing are required (Schön, 1983). Schön (1990) pointed out that beginner practitioners should be helped to acquire certain skills, which can be used in those kind of situations. He argued for a reflective practice that involves: knowing-in-action, reflection-in-action, and reflection-onreflection-in-action. The former refers to know-how, it is tacit, implicit in our patterns of action; the second is learning by doing, when we think about what we are doing and understand it while we do it; the last one occurs when the action is mentally reconstructed. This implies reflective thinking, defined as an active, persistent and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge, taking into account the rationale and the conclusions to which it leads. It is about evidence questioning, in order to introduce new information to confirm whether or not the hypotheses (Dewey, 1997). Reflective thinking in professional education is the way to prepare future professionals to take action in case where established theories do not apply. Schön (1990) believes that giving real situations to trainees can prepare them better to deal with emerging challenges and make decisions under uncertainty, unique and value conflict that characterized real life situations. Beginner practitioners must learn in action, guided by experienced practitioners (coaching), in a protect environment, with low risk of failure.

In this way, people learn from their experience. Forms of experience-based education have been widely accepted and used in the curriculum of undergraduate and professional programs (Kolb, 1984). Lave and Wenger (1999) add that learning is not an isolated act, it occurs in communities of practitioners. Learners are full participants in their communities, in a sociocultural practice. This social process includes the learning of knowledgeable skills.

Along with Schön (1983, 1990), many other authors (Alarcão, 2001; Barbier, 1996; Freire, 1972, 1996; Morin, 1999; Nóvoa, 1992; Parker, 1997; Zeichner, 1993) advocate the importance of reflective and critical thinking on training beginner practitioners to become reflective practitioners; and construct a professional identity. Further, others authors (Canário, 1999; Cornu, 2003; Kolb, 1984) stress practice and professional experience as a source of learning and knowledge; and production of competence and transformation of identity (Barbier, 1996).

Since outreach workers have an educator role in sex work context, we intend to apply this theoretical framework to design a profile definition of the outreach worker in street-based sex work setting.

Problem Statement

The advantages of outreach have been widely documented (Mikkonen et al., 2007; National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), 2002; Needle et al., 2005; Rhodes, 1996; UK Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP), 2008), however little research has been done about educator’s profile in sex work settings (exceptions are Marques, Queiroz, Santos, & Maia, 2013; Mikkonen et al., 2007; TAMPEP, 2009; UK Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP), 2008).

Research Questions

For this study, we designed the following research question: What are the social skills,

theoretical and practical knowledge, attitudes and beliefs that the outreach worker should have?

Purpose of the Study

The study discussed in this paper is embedded in an ongoing PhD action research project. This study has two major purposes: 1) to identify the characteristics of the outreach worker; 2) to understand the role of training and continuous education in this context. We aim to understand the outreach staff opinions, regarding their personal professional experience: beginner (less than one year), intermediate (3 years), advanced (more than 10 years).

Research Methods

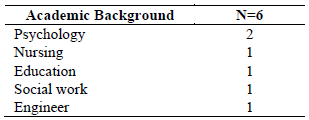

For this study, we interviewed 6 professionals (4 female and 2 male) of an outreach team that provide services for street-based female sex workers, in the city of Coimbra, Portugal. The respondents had between 22 and 44 years old, and less than one year up to 21 years of outreach experience with sex workers. They were from different areas of expertise, as shown in Table 1.

This study has adopted a descriptive and analytic qualitative methodology. Data were collected from July to October 2013, through semi-structured interviews. The interviews were recorded, with the permission of the professionals, and transcribed. We used content analysis to analyze the data, following the principles and procedures described in the specialist literature on this technique (Amado, Costa, & Crusoé, 2013; Bardin, 2004; Ghiglione & Matalon, 2005; Strauss & Corbin, 2007). We sorted the data into a range of categories, as reported below. We also took care to ensure that the respondents were not identified. We also used the WebQDA software.

Findings

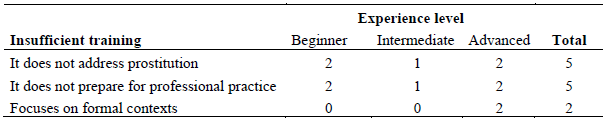

6.1.Academic background and professional experience

Most respondents have expertise on social and health field. They consider that their academic training is not enough to deal with their professionals’ challenges. Academic knowledge does not address the issue of prostitution, has not a practice dimension, focuses predominantly on formal contexts and does not include outreach (table 2).

Beginners’ practitioners even consider prostitution a taboo subject, as evidenced by the

following testimonials:

“We don´t have any subject that addresses prostitution or drugs addiction. Those are hard-to-reach population, the most difficult to work with and we needed to have more knowledge to deal competently. All that I know about prostitution, I only get to know now because I needed for my dissertation. I never talked about it and none of my colleagues, that take counseling classes, talked about these subjects. It seems like it is a taboo.” (Respondent 1).

“[…] we talk a lot, for instances, about AIDS, people with AIDS, but we never talked about prostitution […]” (Respondent 5).

Furthermore, they consider that there is a gap between what they learnt at college and practice;

and their knowledge is far away from reality.

“How to do was one of my main difficulties. I was afraid of doing something wrong, because I don´t know enough to understand different kinds of situations. I don´t know what to say in that moment, I don´t know how to deal with it.” (Respondent 1).

“We weren´t ready to work with this population (…) we have some competencies for design a project, educational projects, projects according with the population, with their needs, although, when I got into the field, after established relationships, I noticed difficulties. College does not prepare us for that.” (Respondent 5).

This feeling is shared by those who are more experienced. For them, college: “It is not enough. It is absolutely insufficient. College does not prepare future professionals to work on the street, or to work with these populations. Also, they prepare people to work in offices and the teachers do not understand or know nothing about field work. "(Respondent 6).

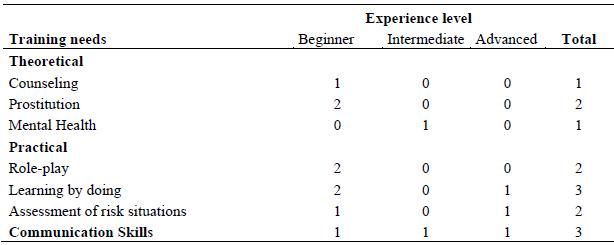

6.2.Training needs

Once they considered that there is a lack in academic training, we tried to understand which areas were identified as priority at this level. Table 3 shows three kinds of needs: theoretical, practical and communication skills. The latter refers to personal development as a way to establish a relationship with sex workers.

Respondents identify needs focus mainly on practical issues and communication skills. The theoretical and practical needs are most identified by the beginners’ practitioners. One respondent, from advanced category, believes that coaching is important, because not everything must be learned by trial and error:" (Respondent 4).

For beginners’ practitioners, sharing experiences, solving problems by using active techniques,

including role-playing, are considered good ways of learning by doing: "[is important] to have training. They [outreach workers] can give us, for example, case studies. Situations’ examples that happened to them, and says to us: 'In this situation we did that, in other we used other strategy'. They could give us options for us to become aware of different scenarios. Because we don´t know nothing, I don´t know what to do… as a trainee, I feel a bit panicky sometimes, in some situations ... "(Respondent 1).

For the respondents it is especially in non-formal education, continuous education in work context, that technical skills are further improved. Formative moments in team and professional experience are considered more important than academic training. This aspect is most valued by those in advanced category. These formative moments are reflection and action, in which we can identify a reflective practitioner.

More experienced practitioners supervise and coach beginner practitioners, encouraging reflexive thinking: "[...] When I came to [institution], first, the [outreach worker] took care of giving me a lot of information and said what was important for me to know. Then, realizing that I haven´t a clear idea about the subject, I asked to attend the [institution] training sessions that take place in high school. I wanted to learn more, to be with people who really know better, because I think that sometimes read is not enough hmmm obviously I got something very basic, but at least I clarified some ideas. I can ask anytime to anyone of them [the staff team] if I have any doubts."(Respondent 1).

On other hand, respondents from advanced category also consider coaching a way of self-

questioning and improvement. Coaching lead to an interactive reflective thinking, in which practitioner question about that (s)he is doing, and develops ability to transmit to other know-how.

In this sense, coaching is considered a way of learning as well: “The volunteers and trainees that came after me have helped me thinking and learning. New people leads me to think about the work. Maybe it [coaching] also turns out to be a way for me of learning… it helps myself thinking differently or to question other issues [...] "( Respondent 4).

However, it is practice experience that gives expertise: knowledge is achieved by doing, as

attested two of the most experienced respondents:

"[...] Much of that I learned - although it is also important common sense and one or another concept learned during the degree - was in day-to-day with people (...) characteristics of good sense and wellbeing with them." (Respondent 6).

“[…] I think that theoretical questions can be framed later in practice, but the practical knowledge is more important, I think, for this kind of work.” (Respondent 6).

"[...] When I began working in this area I had no academic training, I fell from the sky [...] No, I do not know about academic knowledge. In my opinion personal experience is the most important, not academics. My training is more experience than academic."(Respondent 2).

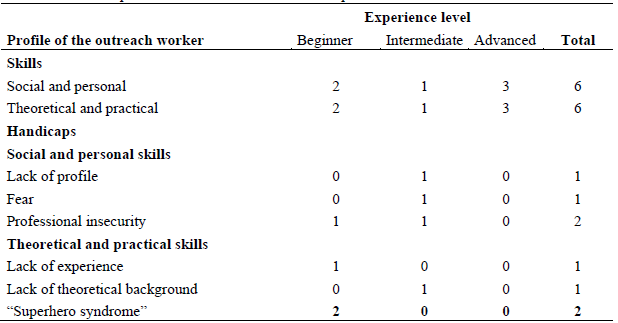

6.3.The ideal profile and outreach worker handicaps

At this point we discuss the characteristics that respondents identified as ideal for outreach workers. We grouped into two categories: social and personal; theoretical and practical skills. The handicaps identified by respondents are also located in these two categories, as shown in Table 4.

The respondents stress the following characteristics: empathy, non-judgmental, strength, authenticity and spontaneity, not prejudiced, believing in what you do, self-confident, willingness to learn, patient, communicative, ability to improvise, etc. In the theoretical and practical skills are included technical skills that allow know-how and expertise in various areas including health - mental, sexual and reproductive - legal or psychosocial, as the following example illustrates:" (Respondent 3).

However, some respondents recognize their limitations, especially the less experienced, who consider that they do not have the profile required for this work. They feel afraid and insecurity about their own capacities. According to respondent 3:

But I always also said, that when I find the right person, I will resign and give my place for that person.” (Respondent 3).

In addition, respondents point out lack of practical experience and theoretical background as handicaps. Moreover, we add “superhero syndrome” item to designate statements that excessively value the academic degree, in detriment of clients’ knowledge. It seems a paradox, since it appears among trainees, but, on the other hand, seems to refer to enhancement of their knowledge and a desire to be helpful. Probably, trainees are not aware of the dangerousness of this believe in relational terms. In opinion of trainees, professionals are fundamental because they have the answers that people need, without which clients would not be able to get autonomy: (Respondent 1).

“If it we were not here, who would help them? […] we, as professionals, help sex workers to access formal services they need. […] sometimes they have difficulties, they do not have studies that allow them to manage themselves and to reach services. In that sense, professionals are important.” (Respondent 5).

Finally, we transcribe an excerpt that seems to more clearly illustrate this paradox “superhero

syndrome”. Here is present a need for work recognition of the work by the clients: "I think the professional is not going to be there forever. The professional is important. I do not know if I'm explaining well. We have to be there for them, but also have to enable them to have autonomy, do things by their own and follow their own path. We will not be with those people forever. In few years, I would like they remember that we helped them, developed their skills. Because an outreach worker is like this, not only solve others’ problems but also empower people to solve their own problems. We are not doing things for them, we help them achieve something.” (Respondent 5).

Conclusions

A good agreement is generally found between respondents, regarding the definition of skills required. Respondents identify two types of skills that an outreach worker should have: 1) social and personal (attitudes and beliefs). In this category, we find communication skills that streamline interpersonal relationship. These skills appear to drawn on work of Carl Rogers (1985); 2) theoretical and practical knowledge. In order words, know-how or expertise in various fields of knowledge. The less experienced reveals a lack of practical and theoretical background as handicaps, which seems to interfere with self-confidence and outreach perception.The lack of professional self-confidence was already brought to discussion by Schön (1983). In his words: The crisis of confidence in the professions, and perhaps also the decline in professional self-image, seems to be rooted in a growing skepticism about professional effectiveness in the larger sense, a skeptical reassessment of the professions’ actual contribution to society ‘s well-being through the delivery of competent services based on special knowledge. (Schön, 1983, p. 13).

Therefore, we believe that this allows us to conclude that a profile definition, as well as a professional identity definition are required, not only to give more confidence to outreach workers, but also to improve the service delivered.

Regarding the role of training and continuous education, the respondents argue for a competence-based education which is associated with experience-based (Kolb, 1984). According to Kolb (1984, p. 41), “learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of the experience. Knowledge results from the combination of grasping experience and transforming it”. In this sense, outreach teams might be considered communities of practitioners (Lave & Wenger, 1999), once the beginner practitioners learn in action, guided by experienced ones. One the other hand, more experienced practitioners learn from the beginners, which reveals an horizontal and democratic relationship between them, as stressed by Freire (1972).

The findings are consistent with the literature that argues for reflective and critical practice (Barbier, 1996; Freire, 1996; Nóvoa, 1992; Parker, 1997; Schön, 1983; Zeichner, 1993);, professional experience as a source of learning and knowledge; and production of competence and transformation of identity (Barbier, 1996; Canário, 1999; Cornu, 2003; Kolb, 1984; Lave & Wenger, 1999; Schön, 1990). Moreover, these findings are consistent with the guidelines provided by Mikkonen et al. (2007); TAMPEP (2009); or UK Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP) (2008).

On the basis of the findings generated by this study, it is concluded that outreach worker is a reflective educator in street-based sex work setting. Academic knowledge is defined as important, but not enough, because it is not always applied in situations of uncertainty, instability, uniqueness and value conflict, namely, real life situations. A reflexive attitude might allow bridging the gap between academic knowledge and professional practices, since reflecting in and on action brings together numerous dimensions of knowledge, as well as helps to develop interpersonal skills to deal with situations of complexity. The street is a place of learning and teaching, in a dynamic and reciprocal interaction, and the outreach worker is an interpersonal relationship professional.

The main contribution of this research is to map an outreach worker’ profile as educator at the street level, however non-formal education in this context remains little studied. Therefore we suggest further research in order to improve the discussion about the need and possible modalities of teaching-learning programs, as well as to help the construction of professional identity of the outreach worker in sex work settings.

Acknowledgements

This research paper is financed by FEDER Funds through the Competitiveness Factors Operational Program- COMPETE and by National Funds through FCT – Foundation for Science and Technology within the project PEst-C/CED/UI0194/2013 - Research Centre “Didactics and Technology in Education of Trainers” (CIDTFF).The present report is part of doctoral thesis also sponsored by FCT - Portuguese national funding agency for science, research and technology (SFRH/BD/78139/2011). The authors also thank Associação Existências.

References

Alarcão, I. (Ed.). (2001). Escola reflexiva e nova racionalidade. Porto Alegre: Artmed Editora. Amado, J., Costa, A. P., & Crusoé, N. (2013). A técnica da análise de conteúdo. In J. Amado (Ed.), Manual de investigação qualitativa em educação (pp. 301–351). Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra.

Barbier, J.-M. (Ed.). (1996). Savoirs théoriques et savoirs d’action. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Bardin, L. (2004). Análise do conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70 .

Canário, R. (1999). Educação de adultos: um campo e uma problemática. Lisboa: Educa. Cornu, R. (2003). Educação, saber e produção. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget.

Dewey, J. (1997). How we think. New York: Dover Publications.

Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogia do oprimido. Porto: Afrontamento.

Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogia da autonomia: saberes necessários à prática educativa. São Paulo: Paz e Terra.

Ghiglione, R., & Matalon, B. (2005). O inquérito: teoria e prática (4a ed reim.). Oeiras: Celta

editora.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. New

Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1999). Situated learning�: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Le Boterf, G. (2003). Desenvolvendo a competência dos profissionais (3a ed.). Porto Alegre:

Artmed.

Marques, J., Queiroz, J., Santos, A., & Maia, S. (2013). European professional profile of the outreach worker in harm reduction. Agência Piaget para o Desenvolvimento - APDES.

Retrieved April 13, 3013, from http://comum.rcaap.pt/handle/123456789/4689 Mikkonen, M., Kauppinen, J., Houvinen, M., & Aalto, E. (2007). Outreach work among marginalised populations in Europe. Guidelines on providing integrated outreach services.

Amsterdam. Retrieved from http://www.correlationnet.org/doccenter/pdf_document_centre/book_outreach_fin.pdf Morin, E. (1999). Os sete saberes para a educação do futuro. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2002). Principles of HIV prevention in drug-using populations. Retrieved from http://www.nhts.net/media/Principles of HIV Prevention (17).pdf Needle, R. H., Burrows, D., Friedman, S. R., Dorabjee, J., Touz, G., Badrieva, L., … Latkin, C.

(2005). Effectiveness of community-based outreach in preventing HIV / AIDS among injecting drug users. International Journal of Drug Policy, 16, 45–57.

doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.02.009

Nóvoa, A. (Ed.). (1992). Os professores e a sua formação. Lisboa: Publicações Dom Quixote.

Parker, S. (1997). Reflective teaching in the postmodern world – a manifesto for education in postmodernity. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Perrenoud, P. (1996). Formation continue et développement de compétences professionnelles. Éducateur, (9), 28–33.

Porter, J., & Bonilla, L. (2010). The ecology of street prostitution. In R. Weitzer (Ed.), Sex for sale.

Prostitution, pornograhy, and the sex industry (2nd ed., pp. 163–185). New York and London: Routledge.

Rhodes, T. (1996). Outreach work with drug users: principles and practice. Strasbourg.

Rogers, C. R. (1985). Tornar-se pessoa (7.a ed.). Lisboa: Moraes Editores.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner. How professionals think in action. [S.l.]: Basic Books.

Schön, D. A. (1990). Educating the reflective practitioner. Oxford: Jossey-bass publishers.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (2007). Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing Grounded Theory (3rd ed.). London: SAGE Publications.

TAMPEP. (2009). Work Safe in Sex Work. A European Manual on Good Practices in Work with and for Sex Workers. Amsterdam: TAMPEP International Foundation.

UK Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP). (2008). Working with Sex Workers: Outreach. UK.

Retrieved April 17, 2013, from http://www.uknswp.org/wp-content/uploads/GPG2.pdf Whowell, M. (2010). Walking the beat: doing outreach with male sex workers. In K. Hardy, S.

Kingston, & T. Sanders (Eds.), New sociologies of sex work (pp. 75–90). Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Zeichner, K. M. (1993). A formação reflexiva de professores: ideias e práticas. Lisboa: Educa.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

06 January 2015

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-001-3

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

2

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-218

Subjects

Educational psychology, education, psychology, social psychology, group psychology, collective psychology

Cite this article as:

Graça, M., & Gonçalves, M. (2015). Towards a profile definition of the educator in street-based sex work setting. In Z. Bekirogullari, & M. Y. Minas (Eds.), Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences – icCSBs 2015 January, vol 2. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 63-73). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2015.01.8