Abstract

This study examined the relationship between moral intelligence, adjustment and identity styles. Participants in study were high school students (250 males) and these students were selected by cluster-randomization. Then moral intelligence scale (Lennick and Kiel), Identity style inventory (ISI-6G) andAdjustment Inventory for School Students -AISS (Sinha & singh) were completed by each member of the sample. The analysis of this research was performed by using Pearson correlation and regression analysis. The finding showed that there is a significant and positive relationship between moral intelligence, adjustment, informational and normative identity style. But, there was no significant relationship between moral intelligence and diffused- avoidant identity style. Also there is no relationship diffused-avoidant identity style and adjustment. The regression analysis showed that there was multiple correlation coefficient between adjustment and informational and normative identity style, with the criterion variable moral intelligence (RS=0/60, p<0/001). The normative identity styles, adjustment, informational identity styles predictor variables, respectively, as a powerful predictor for moral intelligence variable. The Diffuse- avoidant identity style is not a predictive variable for the moral intelligence.

Keywords: Moral intelligence, Identity style, Adjustment

Introduction

Moral intelligence is newer and less studied than the more established cognitive, emotional and social intelligences, but has great potential to improve our understanding of learning and behavior (Clarken, 2009). Moral intelligence is “the mental capacity to determine how universal human principles should be applied to our values, goals, and actions” (Lennick, D. & Keil, 2005). Moral intelligence is not just important to effective leadership- it is the “central intelligence” for all humans. It’s because moral intelligence directs our other forms of intelligence to do something worthwhile. Moral intelligence gives our life purpose. Without moral intelligence, we would be able to do things and experience events, but they would lack meaning. Without moral intelligence, we would not know why we do what we do-or even what difference our existence makes in the great cosmic scheme of things (Lennick, D. & Keil, 2005). Besides, moral intelligence could include recognizing problems, setting goals, deciding on what is the right thing to do, taking action and persevering (Clarken, 2009).

Doug Lennick and Fred Kiel (2011) defined moral intelligence as, the mental capacity to determine how universal human principles should be applied to our values, goals, and action. Borba (2001) defined moral intelligence as the capacity to understand right from wrong, to have strong ethical convictions and to act on them to behave in the right and honorable way. Moral intelligence has different dimension. Lennick and kiel believed that moral intelligence consists the four major dimensions of integrity, responsibility, compassion, and forgiveness and 10 sub- categories (competence), including, integrity, honesty, courage, confidentiality, commitment, personal responsibility, accountability against decisions self-restraint and self-limiting, helping others( responsibility of service to others), caring for others( compassion), understanding the feelings of others (altruism and OCB) and understand their emotional needs(faith, belief and humility). Borba, summarily connects the question of moral intelligence of education to seven major values: empathy, conscience, and self –control, respect, kindness, tolerance, and fairness. The first three- empathy, conscience and self- control- represent the moral core of moral intelligence.

Adolescent is the period in which the foundation for future education, major life roles, relationship, and working toward long-term productive goals are established. Similarly, Adolescence is an important period for the development of preventive interventions which are designed to lead to the development of more serious psychopathology in adulthood. Adolescence as a formative stage plays a significant role in the study of developmental psychopathology because after this maturational interval, it is difficult to change some behavioral and emotional patterns (Moffitt et al., 2001).

Identity formation is one of the key tasks in adolescence. To effectively regulate and govern their lives, individuals need to develop a stable and meaningful identity structure. Most research on individuals̛ approach to the identity formation process has focused on how individuals explore and define their identity (Berzonsky et al., 2011). According to Erikson (1968), a sense of identity 85

emerges as the adolescent copes with social demands and developmental challenges, and attempts to give meaning to his choices and commitments of his life. Marcia̛ s (1966) conceptualization of Erikson̛ s process of identity formation in terms of whether an individual has experienced a crisis (i.e. gone through self-exploration and consideration of alternatives) and whether the individual has become committed to stable sense of identity resulted in the description of four unique identity statues: achievement, foreclosure, moratorium, and diffusion.

Berzonsky (1990) proposed a process model of identity formation that focused on differences in the social-cognitive processes and strategies individuals use to engage or avoid the tasks of constructing, maintaining, and/ or reconstructing a sense of identity: three different social-cognitive identity processing styles are postulated within this model: informational, normative, and diffuseavoidant. Adolescents with an informational identity style are self-reflective and they actively seek out and evaluated self- relevant information before resolving identity conflicts and forming commitments. This style is associated with self-insight, open-mindedness, problem-focused coping strategies, vigilant decision making, cognitive complexity, emotional autonomy, empathy, adaptive self-regulation, high commitment levels, and an achieved identity status (Berzonsky, in press). Individuals with high informational scores tend to define themselves in terms of personal attributes such as personal values, goals, and standards (Berzonsky, 1994; Berzonsky, Macek, & Nurmi, 2003; Lutwak,Ferrari, & Cheek, 1998).

Adolescents with a normative style more automatically adopt and internalize the goals and standards of significant others and referent groups. A normative style is associated with high commitment levels, self-control, and a sense of purpose but also a need for structure and cognitive closure, authoritarianism, inflexibility, a foreclosed identity status and low tolerance for ambiguity (Duriez & Soenens, 2006; Soenens, Duriez, & Goossens, 2005). Adolescents with a diffuseavoidant style procrastinate and attempt to defer facing identity conflicts and problems as long as possible. When they have to act or make choices, their behavior is driven primarily by immediate external demands and consequences. Such situational accommodations, however, tend to be shortterm acts of compliance rather than long-term modifications in their sense of self-identity (Berzonsky & Ferrari, 2009). According to Berzonsky’s model, diffuse-avoidance is more than a fragmented or confused self; it involves strategic attempts to evade or obscure potentially negative self-relevant feedback. A diffuse-avoidant style is associated with weak commitments, an external locus of control, impulsiveness, self-handicapping, and a diffusion identity status (Berzonsky, in press; Berzonsky & Ferrari, 2009). Individuals with a diffuse-avoidant style tend to define themselves in terms of social attributes such as reputation and popularity (Berzonsky, 1994; Berzonsky et al., 2003).

Development of moral intelligence seems to accompany the development of identity. Individuals high in identity (identity achievement) tend to be functioning at high levels of moral reasoning, while subjects lower in identity (identity diffusion) are found to tie at low levels (Podd, 1972). Social adjustment ensuing learning social behavior, is in harmony with social and personal needs. It would be thought through socialization process and by social interactions. (Rayan, Shim, 2005). Adjustment is a major concern in all developmental stages, but is of great relevance during adolescent. Adapting to the changes within themselves and to the changed expectations of the society is a major developmental task of the adolescent stage. Their happiness, aspirations, motivation levels, emotional wellbeing and subsequent achievements are linked to their adjustments with the ever changing internal and external environment. Good adjustments make the adolescents proud and self-satisfied, motivate them for future success, encourage them to be an independent thinking person and build their confidence and in turn improve the mental health. The environment created in the school as well as home either accelerates or retards the development of any pupil (Krishnan, 1977).

A growing corpus of evidence has highlighted that identity styles have a strong impact on adolescent adjustment. In particular, the diffuse-avoidant style has been found to be linked to both externalizing and internalizing problem behaviors. In fact, convergent findings indicated that the diffuse-avoidant style was associated with delinquency (Adams, Munro, Munro, Doherty-Poirer, & Edwards, 2005; White & Jones, 1996), conduct and hyperactivity disorder behaviors (Adams, Munro, Doherty- Poirer, Munro, Petersen, Edwards, 2001).

Furthermore, both the informational and normative styles were positively related to high selfesteem (Nurmi et al., 1997; Phillips & Pittman, 2007), optimism (Phillips & Pittman, 2007), educational purpose (Berzonsky & Kuk, 2000), educational involvement, and career and lifestyle planning (Berzonsky & Kuk, 2005).

There is no published investigation in relationship of moral intelligence, identity styles and adjustment but as moral intelligence is the meaning of nature and human life and its aim to make the interaction between the environment and individual function, according to the discussions (see above) it appears there is relationship between moral intelligence, identity styles and adjustment. On this basis can be used identity styles and adjustment as the criterions for predict moral intelligence in the adolescent. We hypothesized that moral intelligence would be related positively to informational identity style, normative identity style and adjustment. Finally we expected that adolescent with a diffuse- avoidant identity style no significant association to moral intelligence.

Materials and Methods

Population and sample

The statistical population of this study consists of all high school boy student zone 1 city of Shiraz. Participants in study were 250 males and these students were selected by cluster-randomization and complete the questionnaire.

Instrument

Moral Competency Inventory (MCI)

The MCI developed by Lennick’s and Kiel (2005) sets out to measure ten competencies within a moral framework. The competencies are: 1) acting consistently with principles, values and, beliefs; 2) telling the truth; 3) standing up for what is right; 4) keeping promises; 5) taking responsibility for personal choices; 6) admitting mistakes and failures; 7) embracing responsibility for serving others; 8) actively caring about others; 9) ability to let go of one’s own mistakes; 10) ability to let go of others’ mistakes. The first four of the competencies in the MCI claim to measure integrity. Responsibility is measured in competencies five through seven. Compassion is measured in eighth competency. The two end of the competencies in the MCI Claim to measure forgiveness. A five point Likert- like scale (1 = Never; 2 = infrequently; 3 = Sometimes; 4 = in most situations; and 5 = in all situations) remains constant through the forty question instrument. Additive scores of 90 to 100 are considered very high, 80 to 89 high, 60 to 79 moderate, 40 to 59 low, 20 to 39 very low. Martin (2010) reported an acceptable validity for MCI. Cronbach alpha varied 0.65 - 0.84 for 10 subscales.

The Identity Style Inventory – Revised

The Identity Style Inventory - Revised (ISI-6G; Berzonsky, 1992) measures three styles of personal problem solving and decision-making (information orientation style, normative style and diffuse/avoidant style) which represents the general approach an individual uses when dealing with identity related issues [18]. Participants were asked to indicate how much each statement describes them using a 5 point ordered category item ranging from 1 (“not at all like me”) to 5 (“very much like me”). Berzonsky (1992) provides data indicating acceptable levels of reliability and validity. In this sample Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0/591 to 0/749.

Adjustment Inventory for School Students -AISS

This 60 item inventory (Sinha & Singh, 1993) segregates adjusted secondary school students from poorly adjusted students in three areas of adjustment: Emotional, Social and Educational. Responses are taken in ‘yes’ and ‘no’ for each item. The split- half reliability is 0/95. Both Itemanalysis and Criterion related validity is high with product moment correlation between inventory scores and criterions ratings was 0/51. Percentile norms are provided for male and female students separately. Scoring is done manually.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 19. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the collected data. Descriptive statistics included mean, standard deviation, and Pearson correlation coefficient, while inferential statistics included multiple regression.

Results

The results were analyzed with Pearson correlation coefficient and regression analysis ways. The means, standard deviations, and correlations between moral intelligence, identity styles and adjustment are presented in table1.

An informational identity style and normative identity style related positively to moral intelligence and adjustment. There was a positive and significant relationship between adjustment and moral intelligence. There was no significant relationship between diffuse-avoidant identity style and moral intelligence and adjustment. Multiple regression analysis were performed to examine the relationship of moral intelligence, identity style and adjustment in Figure 1, 2.

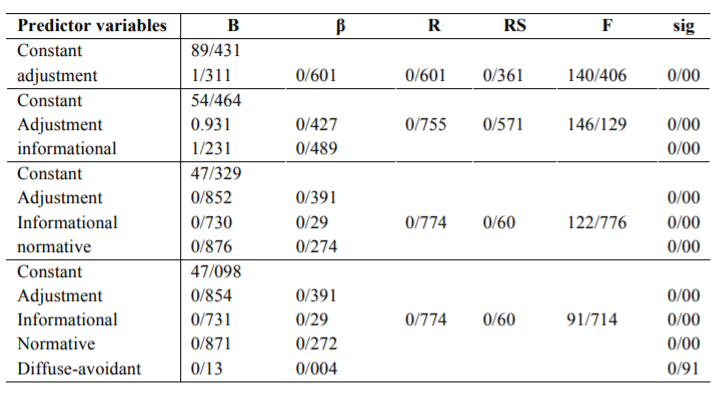

The regression analysis based on the method of enter in Table 2 shows that the set of predictor variables accounted for significant variance in the dependent variable, moral intelligence (RS=0/60, p<0/001). The predictor variables were each significantly correlated with moral intelligence. Thus, there was multiple correlation coefficient between the predictor variables with the criterion variable moral intelligence.

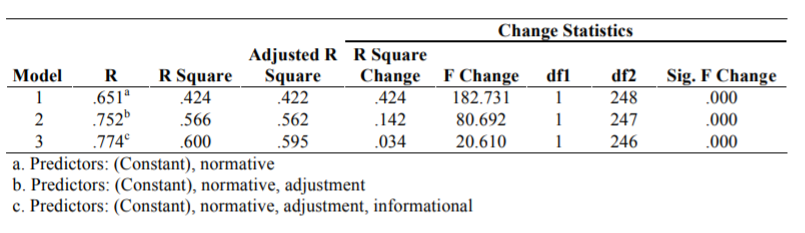

The regression analysisbased on the method of stepwise in Figure 2 shows that among the four predictor variables, respectively, the normative identity style, adjustment, informational identity styles as a powerful predictor for moral intelligence variable. In the first step between normative identity style and moral intelligence is the multiple correlation coefficient (RS=0/42, p<0/001). In the second step, by adding adjustment with the normative identity style multiple correlation coefficient is RS= 0/56, p<0/001. Finally the third stage, the information identity style was added with the normative identity style and adjustment, multiple correlation coefficient is RS= 0/60, p<0/001. The Diffuse- avoidant identity style is not a predictive variable for the moral intelligence.

Discussion

This study showed that there are a positive and significant correlation between moral intelligence, informational and normative identity styles and adjustment. In the other word, it can be cited that increasing the scores of adjustment, informational and normative identity styles will increase moral intelligence.

Religious values and moral development in adolescence than at any other period of rapid growth in adolescence leads to a better understanding of the ethical and religious values and judge. In dealing with these issues more closely and show more complex. The vast emotional and social development and meet the needs of adolescents living with parental expectations, And in dealing with these issues and more complex reactions show closer. As well as the vast emotional and social developments and the face of parental expectations and requirements of life with kids, friends, new experiences, and those in their social and cultural relations, in making ethical and value issues with them more, and their growth in these fields, expand it. The result of this situation is it that teens with a wide collection of inner and outer changes and conflict resulting from social and cultural and religious values of the face, and have a safe place to find their own growth and durability. The task of selecting the appropriate norms for currencies and living with the problem is the complexity of the cell together. Form a new capacities to understand the moral and religious values of the hand and on the other hand the right to deal with enough experience complex moral and religious values and issues that comes to them in everyday life do not advance. However, they should take a decision at any moment and when different solutions and value to select a more appropriate way. Recognition and definition of their identity documents and required adolescent features religious and moral value to as well. He must have these characteristics to identify themselves in order to be entitled to use a strong identity.

Adolescents with an informational identity styleare characterized as highly committed “selfexplorers” in that they address identity-relevant issues by being skeptical of their self-views, questioning their assumptions and beliefs, and exploring and evaluating information that is relevant to their self-constructions (Berzonsky, 1992; Berzonsky & Sullivan, 1992). The use of an informational style is positively associated with strategic planning, vigilant decision making, and the use of proactive and problem-focused coping (Berzonsky, Nurmi, Kinney, & Tammi, 1999; Berzonsky & Sullivan, 1992; Seaton & Beaumont, 2008). The informational style is also associated with such personal and cognitive attributes as autonomy, openness to experience, introspectiveness,

self-reflection, empathy, a high need for cognition, and a high level of cognitive complexity (Berzonsky, 1993; Berzonsky& Sullivan, 1992; Berzonsky et al., 1999; Soenens, Berzonsky, Vansteenkiste, Beyers, & Goossens, 2005).

Adolescents who use a normative identity styleaddress identity-relevant issues By “conforming to the prescriptions and expectations of significant others” (Berzonsky & Kuk, 2000). Normative individuals report high levels of identity commitment as well as dispositional characteristics such as agreeableness, extraversion, and conscientiousness (Dollinger, 1995). However, they also report low levels of openness and introspectiveness, and they have been found to employ avoidant coping strategies, to procrastinate in the face of decisions, to have a high need for structure and a low tolerance for ambiguity, and to be conservative, authoritarian, and racist in their sociocultural views (Berzonsky, 1992; Berzonsky & Sullivan, 1992; Dollinger, 1995; Soenens, Duriez, & Goossens, 2005).

Individuals who are low in identity commitment tend to use a diffuse-avoidant identity style; these individuals are “reluctant to face up to and confront personal problems and decisions” (Berzonsky & Kuk, 2000). The use of a diffuse-avoidant style is characterized by low agreeableness, conscientiousness, introspectiveness, and cognitive complexity, and high neuroticism (Berzonsky, 1993; Berzonsky et al., 1999; Dollinger, 1995). A diffuse-avoidant style is also associated with less adaptive cognitive and behavioral strategies, such as using avoidant coping strategies, engaging in task-irrelevant behaviors, expecting to fail, having a low feeling of mastery, and performing less strategic planning (Berzonsky, 1992;; Nurmi, Berzonsky, Tammi, & Kinney, 1997).

Identity style has been found to be an important predictor for adjustment, with the normative and informational styles associated with better adjustment than the diffuse- avoidant style. Diffuseavoidant individuals score higher on depression, delinquency, conduct disorder, and hyperactivity than do informational or normative individuals (Adams, Munro, Munro, Doherty- Poirer, & Edwards, 2005; Nurmi et al., 1997). However, when maturity of adjustment is considered, subtle differences emerge for the informational and normative styles. For example, among entering university students both the normative and informational styles were found to positively predict educational purpose, but only the informational style positively predicted academic autonomy and mature interpersonal relationships (Berzonsky & Kuk, 2000). Informational individuals scored higher than normative individuals on life management and emotional autonomy as resources for dealing with the challenges of university life (Berzonsky & Kuk, 2005). Similarly, Vleioras and Bosma (2005) found that, although both the normative and the informational styles were positively related to environmental mastery, the informational style was uniquely associated with well-being in the form of having positive relationships with others, autonomy, personal growth, and a purpose in life. Berzonsky,ciecuh, duriez, and soenens( 2011) found that an informational identity style was positively associated with values emphasizing independence( openness rather than conservation). Whereas a normative identity style was positively associated with values such as security and tradition. A diffuse- avoidant identity style was positively associated with values that highlighted self- interest such as hedonism and power.

So adolescents with a stable and meaningful identity structure, can maintain a sense of selfcontinuity over time and place, which is a framework for decision-making, problem-solving and interpretation of their experiences it provides. Having this identity structure probably identifying features like honesty, responsibility, self-control, understanding the feelings of others, empathy and kindness spread, that these characteristics with what already was said to explain the dimensions of a moral intelligence, is relevant. So identifying identity styles may be predictor of moral intelligence. There is a little research literature reported of moral intelligence and its dimension, however no published research reported the relationship of moral intelligence, identity styles and adjustment. Today, researchers are interested in the moral intelligence. Attention to the moral intelligence is the meaning of nature and human life, economics prosperity and social and free communication honest and civil rights (Gardner, 2000).

The term adjustment is often used as a synonym for accommodation and adaptation. So if adolescent can be the emotional, social, educational and self-adapt to the social environment and healthy relationship can be established between itself and its ability to belong to a group. Adolescent who get a high score in terms of adjustment, they are independent and responsible, able to make decisions, to maintain sobriety and moderation in life and their plans for the future, Such adolescents have the social skills such as active listening, empathy, non-verbal communication and recognize your emotions, self-control, empathy and responsibility as well as the characteristics of their moral intelligence capabilities increase, as a result of the present study confirm this hypothesis.

Being moral is a complex, difficult and lifelong process as is developing moral intelligence. They both require conscious knowledge, guided by positive affect that is carried out in virtuous action. One cause of immorality is ignorance which is sometimes manifested in blind acceptance of others' beliefs without adequately investigating the truth for ourselves.

The various lists of characteristics of moral intelligence can be compared to the moral principles of truth, love and justice to see how inclusive and useful they are. For example, Linnick and Kiels’ competencies of acting consistently with principles, values, and beliefs; telling the truth and admitting mistakes and failures can be understood as aspects of the principle of truth. Love encompasses the competencies of actively caring about others, letting go of one’s own mistakes, letting go of others’ mistakes and embracing responsibility for serving others. Justice includes the competencies of standing up for what is right, keeping promises and taking personal responsibility. Adolescent who get a high score in terms of adjustment, they are independent and responsible, able to make decisions, to maintain sobriety and moderation in life and their plans for the future, Such adolescents have the social skills such as active listening, empathy, non-verbal communication and recognize your emotions, self-control, empathy and responsibility as well as the characteristics of their moral intelligence capabilities increase, as a result of the present study confirm this hypothesis.The first and most important step is for educators themselves to model and value moral knowledge, virtues, commitment and competencies. Education should foster the integrity, responsibility, forgiveness and compassion identified by Lennick and Kiel, and the virtues of empathy, conscience, self-control, respect, kindness, tolerance and fairness recommended by Borba through the principles of truth, love and justice .When leaders and teachers model the competencies of moral intelligence, when they exemplifying the virtues they seek to inspire in their students, they play a key role in transforming their schools, classrooms and students. If we wish to effectively address the manifold problems that face our lives, societies and world, we will actively strive to develop moral intelligence in all (Clarken, 2009).

According to a present study in moral intelligence and its importance, further research should be carried out to identify the variables most associated with moral intelligence.

References

Adams, G. R., Munro, B., Munro, G., Doherty- Poirer, M., & Edwards, J. (2005). Identity processing styles and Canadian adolescents’ self-reported delinquency. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 5, 57–65.

Berzonsky, M. D. (1990). Self- construction across the life-span: A process view of identity development. In G. H. Neimeyer & R. A. Neimeyer (Eds.). Advances in personal construct psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 155–186). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Berzonsky, M. D. (1992). Identity style inventory (ISI-3): Revised version. Unpublished measure, State University of New York, Cortland, NY.

Berzonsky, M. D. (1992). Identity style and coping strategies. Journal of Personality, 60, 771–788.

Berzonsky, M. D. (1993). Identity style, gender, and social-cognitive reasoning. Journal of Adolescent Research, 8, 289–296.

Berzonsky, M. D. (1994). Self-identity: The relationship between process and content. Journal of Research in Personality, 28, 453–460.

Berzonsky, M. D. (in press). A social-cognitive perspective on identity construction. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles, (Eds.). Handbook of identity theory and research. New York: Springer.

Berzonsky, M. D., & Ferrari, J. R. (2009). A diffuse-avoidant identity processing style: Strategic avoidance or self- confusion? Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 9, 145–158.

Berzonsky, M. D., & Kuk, L. S. (2000). Identity status, identity processing style, and the transition to university. Journal of Adolescent Research, 15, 81–98.

Berzonsky, M. D., & Kuk, L. S. (2005). Identity style, psychosocial maturity, and academic performance. Personal and Individual Differences, 39, 235–247.

Berzonsky, M. D., & Sullivan, C. (1992). Social-cognitive aspects of identity style: Need for cognition, experiential openness, and introspection. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7, 140–155.

Berzonsky, M. D., Cieciuch, J. Duriez, B., & Soenens, B. (2011). The how and what of identity formation: association between identity styles and value orientations. Personality and individual difference, 50, 295-299.

Berzonsky, M. D., Macek, P., & Nurmi, J. E. (2003). Interrelationships among identity process, content, and structure: A cross-cultural investigation. Journal of Adolescent Research, 18, 112–130.

Berzonsky, M. D., Nurmi, J. E., Kinney, A., & Tammi, K. (1999). Identity processing style and cognitive attributional strategies: Similarities and differences across different contexts. European Journal of Personality, 13, 105– 120.

Borba, M. (2001). The step by step plan to building moral intelligence. Available from: www.parenting bookmark.com/pages/7virtus.htm

Clarken, R. H. (2009). Moral intelligence in schools. Schools of education, northern Michigan university.1-7.

Dollinger, S.M. C. (1995). Identity styles and the five-factor model of personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 29, 475–479.

Duriez, B., & Soenens, B. (2006). Personality, identity styles, and authoritarianism. An integrative study among late adolescents. European Journal of Personality, 20,397–417.

Duriez, B., Soenens, B., & Beyers, W. (2004). Personality, identity styles, and religiosity: An integrative study among late adolescents in Flanders (Belgium). Journal of Personality, 72, 877–908.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton,

Gardener, jr., r., p. (2000). Emotional intelligence and the impacts of morality. Retrieved for http://www.info.com

Ghazanfari, A. (2005) Reliability and Validity of Identity Style Inventory (ISI-6G). 2004. Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies in Education and Psychology, 4, 227-224 [Persian].

Krishnan, A.P., (1977). Non-intellectual factors and their influence on academic-achievement. Psy. Stu., 22: 1-7.

Lennick, D. and Keil, F.K. (2005). Moral Intelligence. Pearson Education, Inc. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, 1-7.

Lennick, D. and Kiel, F. (2011). Moral Intelligence 2.0: Enhancing Business Performance and Leadership Success in Turbulent Times. Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River.

Lutwak, N., Ferrari, J. R., & Cheek, J. M. (1998). Shame, guilt, and identity in men and women: The role of identity orientation and processing style in moral affects. Personality and Individual Differences, 25, 1027–1036.

Marcia, J.E. (1966). Development and validation of ego- identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology; 3, 551–558.

Martin, D.E. (2010) Moral Competency Inventory Validation: Content, Construct, Convergent and Discriminant Approaches. Management Research Review, 33, 437-451.

Moffitt, T.E., A. Caspi, M. Rutter and P.A. Silva, 2001.Sex Differences in Antisocial Behavior: Conduct Disorder, Delinquency and Violence in the Dunedin Longitudinal Study. 1st Edn., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK., pp: 300.s

Nurmi, J. E., Berzonsky, M. D., Tammi, K., & Kinney, A. (1997). Identity processing orientation, cognitive and behavioural strategies and well-being. International Journal of Behavioural Development, 21 (3), 555–570.

Phillips, T. M., & Pittman, J. F. (2007). Adolescent psychological well-being by identity style. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 1021–1034.

Podd, M.H. (1972). Ego Identity Status and Morality: The Relationship between Two Developmental Constructs. Dereloprnenral Psychology, 6, 497-507.

Ryan, A.M. & Shin, S. (2005). Social achievement goals: the nature and consequences of different orientations toward social competence.University of Illinois, urbana- champaign.

Seaton, C. L., & Beaumont, S. L. (2008). Individual differences in identity styles predict proactive forms of positive adjustment. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 8, 249–268.

Sinha, A. K.P., Singh, R.P. (1993) Manual for Adjustment Inventory for School Students.

Agra National psychological Corporation.

Soenens, B., Berzonsky, M. D., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., & Goossens, L. (2005).

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

06 January 2015

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-001-3

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

2

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-218

Subjects

Educational psychology, education, psychology, social psychology, group psychology, collective psychology

Cite this article as:

Aalbehbahani, M. (2015). Moral intelligence, identity styles and adjustment in adolescent. In Z. Bekirogullari, & M. Y. Minas (Eds.), Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences – icCSBs 2015 January, vol 2. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 84-94). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2015.01.10