Abstract

Sex workers are rarely involved in the design, implementation and evaluation of projects that concern them. Usually, these are run by NGOs and focus mainly on harm reduction and HIV prevention. The purpose of this study is to understand the needs of a group of street-based female prostitutes. We aim to assess and understand their opinions about the service, and any inherent discrimination, provided by the outreach teams. As the first, planning, step of an action research project, this study has adopted a descriptive and analytic qualitative methodology. Data were collected through participant observation, informal interviews (field notes), and 12 semistructured interviews. We concluded that outreach is essential for the respondents, who emphasize the need to control STI. The intervention suggestions made by the respondents reveal the empowering effect of including them in socio-educational projects.

Keywords: prostitution, outreach, non-formal education, empowerment, stigma

1. Introduction

Although increased and diversified research is being carried out on sex work (Weitzer, 2009), the existing literature still tends to focus on the relationship between prostitution and epidemiology (Day & Ward, 2004; Vanwesenbeeck, 2001). The services provided by NGOs to sex workers (SW) follow the same line, concentrating mostly on health promotion and STI prevention, as shown in Agustin (2007); Cooper, Kilvington, Day, Ziersch, and Ward (2001); Crosby (1998); Day and Ward (2004); Mckeganey and Barnard (1996); Pitcher (2006); Sanders, O’Neill, and Pitcher (2011); Spice (2007); Weiner (1996), and others. These services follow guidelines from such organizations as the UK Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP), (2008), or TAMPEP (2012). In Portugal, the situation is quite similar. In the city (Coimbra) where this study takes place, several outreach teams provide harm reduction services to hard-to-reach populations. Despite the fact that the advantages of outreach have been widely documented (Mikkonen, Kauppinen, Houvinen, & Aalto, 2007; National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), 2002; Needle et al., 2005; Porter & Bonilla, 2010; Rhodes, 1996; UK Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP), 2008), prostitutes are rarely involved in designing, implementing and evaluating projects that concern them.

The study discussed in this paper is embedded in an ongoing PhD action research project†. Our purpose is to understand the needs of a group of street-based female prostitutes, in terms of the mechanisms of social exclusion, prejudice and stigma that can lead to discrimination and hence compromise their fundamental human rights. As the first, planning, step of an action research project, this study has adopted a descriptive and analytic qualitative methodology. We aim to encourage all stakeholders (SW, outreach staff members and researchers) to participate in the construction of a socio-educational model of intervention, through critical thinking, reflection, decision-making, responsibility and coconstruction. Stakeholder contribution is important since it may enable a shift in the perspectives presented in traditional research. These tend to emphasize the relationship between prostitutes and pathology, with the women seen as victims and unable to make choices about their life and work (Chapkis, 1997; Magalhães & Silva, 2008; Oliveira, 2011; van der Meulen, 2011).

We used ethnographic techniques such as participant observation and informal interviews (Burgess, 1984; Costa, 1986; Spradley, 1979), and conducted 12 semi-structured interviews to answer the following research question: 1) What is the prostitutes’ opinion about the traditional epidemiological services provided by outreach teams?

2. Theoretical issues: Sex work stigma

Political, social and hygiene discourses have been largely responsible for the social construction of the prostitute stereotype. In ancient societies, sex work was occasionally accepted (Roberts, 1996), but, generally, it is most associated with deviant behavior and crime. Society still consider prostitutes to be deviants, since they defy the gendered rules of honour/dishonour (Pheterson, 1993) imposed by patriarchal discourses (Bourdieu, 1999) and the social construction of gender (Bourdieu, 1999; Piscitelli, 2005; Scott, 1995). These discourses make prostitutes vulnerable to exclusion, discrimination and stigmatization. To date, numerous studies (Day, 2007; Lazarus et al., 2012; Levin & Peled, 2011; Ross, Crisp, Mansson, & Hawkes, 2011; Scambler, 2007; Weitzer, 2010) have shown a relationship between stigma and sex work and the consequences of this for the wellbeing of sex workers. Stigma and stigmatization are linked to the reproduction of inequality, discrimination and exclusion (Scambler, 2007), and is even present in countries where sex work is a legal job (Abel, 2010; Weitzer, 2010).

According to Goffman (1963, p. 3), stigma refers to “an attribute that is significantly discrediting”. It is the result of an interactive social process, which involves the relationship between an attribute and a stereotype. In Goffman’s point of view, stigmatized persons hold the same beliefs about themselves as society does, so they manage the information in order to preserve their spoiled identity. Scambler (1998, 2004), in his studies of health issues, distinguished enacted

stigma (internal stigma or self-stigmatization) from felt stigma (external stigma). The former refers to actual discrimination or unacceptability, the second to the fear of being discriminated against. Link and Phelan (2001); however, re-conceptualized stigma as the co-occurrence of five components: labeling, stereotyping, separating, status loss and discrimination. Working in conjunction with social, economic and political power, these components generate stigma. Unlike Goffman, Link and Phelan (2001) state that stigma is dynamic, meaning that stigmatized persons could be empowered. Resistance is seen as a way of producing social change, so people living with stigma should not be seen as passive, helpless or submissive victims (Link & Phelan, 2001; Riessman, 2000). However, stigma is difficult to eradicate because of the discrimination it engenders. Link and Phelan (2001)argued that a range of aspects and mechanisms need to be taken into account if stigma is to be changed. Thus, they proposed a multifaceted multi-level approach, designed to: 1) produce fundamental changes in attitudes and beliefs; or 2) change the power relations that enable dominant groups to act according to those of their attitudes and beliefs that lead to stigmatization.

In this context, the concepts of power and empowerment require a brief discussion. Generally, power is conceptualized as an instrument of dominance, control and oppression in an unequal relationship. Foucault (2008) understands power as a diffuse historical construction, exercised in context and not possessed by some social classes. In fact, as power is linked to the social, political and economic context, it can be changed. Consequently, it makes sense to conceive empowerment as “a process, a mechanism by which people, organizations, and communities gain mastery over their affairs” (Rappaport, 1987, p. 122). For Rowlands (1995) empowerment cannot be understood without reference to power itself. She saw empowerment as being about the participation of those who are excluded from the decision-making process. It should “lead people to perceive themselves as able and entitled to occupy that decision-making space” (Rowlands, 1995, p. 102).

It can be difficult to empower sex workers because of enacted stigma. Symbolic violence (Bourdieu, 1989) and hegemonic discourses explain the internalized oppression and domination. Symbolic power legitimizes power inequalities, therefore stigmatized individuals or groups can find it difficult to resist (Parker & Aggleton, 2003). Moreover, the “helping” services provided to sex workers may actually trigger dependence, instead of promoting any effective participation (Agustin, 2007). Abel (2010), writing about harm reduction services, states that numerous studies have indicated that programs work best when sex workers are involved as decision makers and actors.

We intend to apply this theoretical framework to help us understand the prostitutes' opinions about the support services provided to them. As this is an action research project, we also aim to find out how can we mobilize the dynamics of non-formal education, understood as a process of liberation and emancipation (Freire, 1972), to combat stigmatization.

3. Methods

3.1.Participants

For this study, we contacted 49 street-based female SW and formally interviewed 12 of them. Most of them work in the city center at night but some of them work along main roads during the day. Our inclusion criteria for the interviewees were as follows: 1) being a street-based female sex worker; 2) being available and interested in cooperating with the ongoing research.

3.2.Data collection and analysis

Data were collected from September 2012 to September 2013, through informal interviews, participant observation, recorded in a field diary, and semi-structured interviews. The interviews were recorded, with the permission of the SW, and transcribed. We used content analysis to analyze the data, following the principles and procedures described in the specialist literature on this technique (Amado, Costa, & Crusoé, 2013; Bardin, 2004; Ghiglione & Matalon, 2005; Strauss

& Corbin, 2007; Vala, 1986). We sorted the data into a range of categories, as reported below. We also took care to ensure that the respondents were not identified. We also used the WebQDA software, because of its potential for online collaborative work (Neri de Souza, Costa, & Moreira, 2011) and the size of the corpus being analyzed.

4. Findings

This section presents our data, with formal interview and fields note (FN) data differentiated. We also include field notes relating to other sex workers (other SW). Quotes from respondents’ were translated in a way that preserves meaning, so are not necessarily

4.1.Evaluation of outreach services

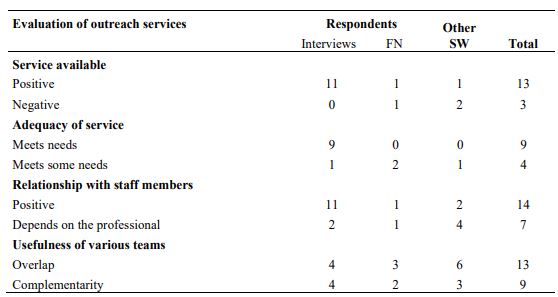

In answering our research question, we began by trying to understand how SW assess outreach and what their perception of it is. The results of this are shown in Table 1.

The service provided by all the outreach teams is widely regarded as positive. The respondents claim that it is good,

useful and important:

The three negative opinions are related to the fact that some teams do not respect the sex workers’ setting, interfering with their activity. This is corroborated by observation, since we found that most teams approach the SW when they are with other teams or negotiating with clients. Respondents have pointed out the need for teams to coordinate, to avoid overlap.

From the SW point of view, the service is satisfactory but sometimes unresponsive to certain needs. Examples of these are the provision of more preventive material and the services for drug users, including the discontinuation of harm reduction projects:

The relationship with the outreach staff members is described as friendly, empathic, even-handed and respectful, as exemplified by the following statements:

However, not all the relationships are of equal value, there are some outreach workers they feel closer to, as a respondent noted: Other respondents pointed out that there are outreach workers they avoid because they are judgmental and show no respect or empathy:

The differing relationships with the outreach workers is mentioned a number of times. Conversational content also varies and seems to depend on the outreach worker’s gender, as the following example illustrates:

As regards the usefulness of the various outreach teams in Coimbra, we have found, through participant observation, that some agencies complement each other as they distribute other types of support, such as food. However, there is overlap and the SW notice it at the following levels:

1) They all provide condoms, but none of them offers syringes:

2) “Before they [the outreach teams] came one after the other. All of them delivering the same stuff” (Liliana).

“[...] But there are many offering condoms, there are too many" (Patrícia).

They work to the same timetable and in the same areas:

“Today the other [institution] team has already been here, and now it’s your turn” (Rute).

“There are others like you that come here. Your team is not the only one that comes here” (Sara).

4.2.Perception of the outreach service

The outreach service is perceived by the SW as a condom delivery service. In some cases, though, they mentioned aspects relating to emotional support and education, as shown in Table 2.

The perception of the outreach service as a condom distribution service is a simplistic one. This is confirmed through direct contact, with the SW referring to teams as "condom girls or ladies" and often only speaking to them to request condoms:

This idea is reinforced in the formal interviews, when we asked the SW to assess the outreach service, with answers like the following:

Although this is a somewhat reductive view of outreach, SW justify its importance as being a way of saving money:

It is worth mentioning here that SW often do not want or need condoms, but do want to engage in conversation with the outreach workers. This suggests that the condom dimension is not as important as it may appear to be from their speech. It is in this way that outreach plays an emotional support role:

Additionally we observed SW appreciation for this emotional support, through their gratitude at being able to let off steam (FN n.61 |09.07.2013) or for having received counselling (FN n.24| 28.02.2013).

The SW who said they did not need outreach services for condoms appreciated the company and emotional support offered by the team, as in:Simultaneously they see outreach staff as part of their social network and something they can rely on. They fulfil social, instrumental and companionship functions, which all seem to be very important:

We also found evidence of an educational aspect to outreach:

4.3.Proposals for improving the outreach service.

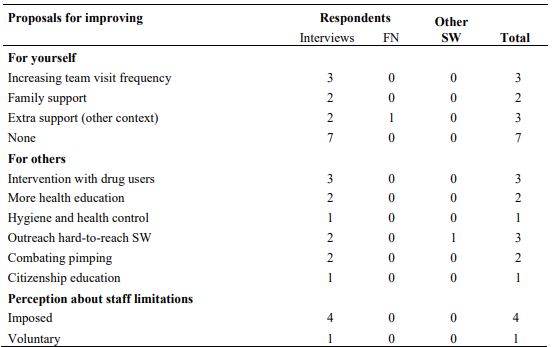

As for potential improvements to the outreach service, we distinguish those that are intended to directly benefit the respondent (for yourself) from those that are of indirect benefit (for others). As Table 3 shows, the respondents emphasized their satisfaction with the service provided, so no improvement is required. This finding is consistent with their assessment of the service.

The proposed “for yourself” improvements included the need to increase the frequency of visits and develop support in a different environment off the streets, as a complement to the outreach services. These are associated with the request for emotional support and social companionship, as well as support for other difficulties and needs, as can be seen from the following statement:

As regards indirect benefits (for others), most of the proposed improvements relate to the prevention, detection and control of STI, especially HIV/AIDS. SW mention the need for syringes and for the treatment and rehabilitation for drug addicts; the encouraging of regular condom use; HIV testing and intervention with hard-to-reach SW, who use drugs and avoid contact with the outreach workers. These proposals are justified by the SW argument that drug users do not use condoms in commercial sex and apply lower prices. Some clients are also reported to offer more money for unsafe sex, thus distorting service prices. SW make the following claims: 1) if drug addicts start using condoms they will expose the

other SW to lower STI risks, as they say the clients tend to be the same and the condoms sometimes break; 2) more health monitoring and the establishment of prices could make competition fairer; 3) on another level, the fight against drug abuse decreases the lack of safety in the workplace (assaults). This is how they want to protect themselves and their business.

At the same time, they also believe that pimping, violence or coercion should be curtailed:

They suggest the involvement of the outreach teams in these situations

As for citizenship, we have identified references to the allocation of responsibility. Raquel believes that the other SW do not value the outreach team efforts, as they only demand things and never show gratitude. She states that, in their opinion, the government is obliged to provide this service:

They explain that most of the proposals are difficult to implement, because the outreach workers already do everything they can (enforced). However, one respondent noted that they are not willing to make changes (voluntary), such as combating pimping.

Finally, we tried to understand why they had agreed to participate in the study. Responses show the SW wished to fulfill their commitment to the researcher. Three main reasons were given: 1) because the researcher asked and it was a form of repayment; 2) it was an opportunity to let off steam; and, most commonly, 3) SW believe their contribution could make a difference and play a key role in the process of change. This reveals the empowering that can occur when SW are included in socio-educational projects:

5. Discussion and Conclusions

These findings suggest that street-based sex workers are satisfied with the services provided by outreach teams. Respondents consider outreach important, because staff members provide condoms and emotional support. They report a positive affective and educational relationship with these workers, who they consider part of their social network. They do not believe many improvements need to be made to the service, although they suggest more intervention with drug addicts; coordination between teams to avoid overlap; more health and citizenship initiatives; combating pimping and violence against prostitutes. This urgent need for intervention with drug users is possibly associated with long-standing disputes between addicts and non-consumers (Mckeganey & Barnard, 1996; Porter & Bonilla, 2010). Although SW suggestions seems to reflect both types of stigma proposed by Scambler (2004), these reveal the empowerment involved in including SW in socio-educational projects. Additionally, SW perceive themselves as social actors and are aware of their own capacity for improvement. These findings are consistent with literature that argues for sex work choice and

agency (Chapkis, 1997; Delacoste & Alexander, 1998; Pheterson, 1993) and the importance of empowerment (Rowlands, 1995; van der Meulen, 2011).

Outreach is described, in a simplistic way, as condom distribution. However, it is also a way to obtain emotional support and has a health education component, mainly focused on STI. This study suggests that traditional interventions focused on epidemiology do not make prostitutes feel stigmatized or discriminated against, on the contrary, they consider these essential and emphasize the need for the control of STI. These findings differ from other studies that claim SW refuse to be labeled and controlled in this way (Mak, 2004).We questioned whether this position reflects the enacted stigma, reproduces the hygienist and moralistic discourse or is a simply health concern.

One limitation of this study is that we were unable to interview any drug user, since they avoid contact. This limitation reinforces the sex workers’ suggestion that action should be taken with such people, since they are the hardest to reach.

Regarding the action research aspect, these findings suggest that both theoretical and practical interventions are required at the following levels:

1) SW should be more enlightened about the purpose of outreach, otherwise this will easily be reduced to being

2) seen as a charity-based condom delivery service;

2) SW suggestions for improvements should be applied and evaluated by all stakeholders;

3) Outreach workers also have an important role as educators in different areas, such as promoting health and

4) empowerment or combating discrimination, stigma and social exclusion. As they operate on the street, where

non-formal education is poorly studied, we propose that future research should concentrate on adapting

educational needs to this particular context;

More participatory research with the target public of support projects is required, as a way of empowering

individuals and taking action on their priorities.

Acknowledgements

This research paper is financed by FEDER Funds through the Programa Operacional Fatores de Competitividade (COMPETE), and by national funds from the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) - within the scope of the project PEst-C/CED/UI0194/2011. The present report is part of doctoral thesis also funded by FCT (SFRH/BD/78139/2011). The authors also thank the sex workers, Associação Existências and Professor Timothy Oswald.

References

Abel, G. (2010). Decriminalisation: A harm minimisation and human rights approach to regulating sex work. University of Otago, Dunedin.

Agustin, L. M. (2007). Questioning solidarity: Outreach with migrants who sell sex. Sexualities, 10(4), 519–534.

doi:10.1177/1363460707080992 Amado, J., Costa, A. P., & Crusoé, N. (2013). A técnica da análise de conteúdo. In J. Amado (Ed.), Manual de investigação qualitativa em educação (pp. 301–351). Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra.

Bardin, L. (2004). Análise do conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70 .

Bourdieu, P. (1989). O poder simbólico. Lisboa: Difel.

Bourdieu, P. (1999). A dominação masculina. Oeiras: Celta.

Burgess, R. G. (1984). In the field: An introduction to field research. London: Routledge.

Chapkis, W. (1997). Live sex acts: Women performing erotic labor. New York: Routledge.

Cooper, K., Kilvington, J., Day, S., Ziersch, A., & Ward, H. (2001). HIV prevention and sexual health services for sex workers in the UK. Health Education Journal, 60(1), 26–34.

Costa, A. F. da. (1986). A pesquisa de terreno em sociologia. In A. S. Silva & J. M. Pinto (Eds.), Metodologia das ciências sociais (pp. 129–148). Porto: Edições Afrontamento.

Crosby, S. (1998). Health care provision for prostitute women: a holistic approach. In J. E. Elias, V. L. Bullough, V.

Elias, & G. Brewer (Eds.), Prostitution. On whores, hustlers, and johns (pp. 408–419). New York: Prometheus Books.

Day, S. (2007). On The Game.Women and sex work. London: Pluto Press.

Day, S., & Ward, H. (2004). Approaching health through the prism of stigma: research in seven European countries. In S.

Day & H. Ward (Eds.), Sex work, mobility and health in Europe (pp. 139–159). London: Kegan Paul Limited. Delacoste, F., & Alexander, P. (1998). Sex work. Writings by women in the sex industry (2nd ed.). California: Cleis Press. Foucault, M. (2008). Microfísica do poder (26th ed.). São Paulo: Edições Graal.

Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogia do oprimido. Porto: Afrontamento.

Ghiglione, R., & Matalon, B. (2005). O inquérito: teoria e prática (4a ed reim.). Oeiras: Celta editora.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Lazarus, L., Deering, K. N., Nabess, R., Gibson, K., Tyndall, M. W., & Shannon, K. (2012). Occupational stigma as a primary barrier to health care for street-based sex workers in Canada. Cult Health Sex, 14(2), 139–150.

doi:10.1080/13691058.2011.628411 Levin, L., & Peled, E. (2011). The attitudes toward prostitutes and prostitution scale: A new tool for measuring public attitudes toward prostitutes and prostitution. Research on Social Work Practice, 21(5), 582–593.

doi:10.1177/1049731511406451 Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 363–385.

Magalhães, R., & Silva, M. J. (2008). Modelos de promoção da saúde num projecto de apoio a prostitutas/os. Sexualidade & Planeamento Familiar, 48/49, 29–34.

Mak, R. (2004). Health care for sex workers in Europe. In S. Day & H. Ward (Eds.), Sex work, mobility and health in Europe (pp. 123–138). London: Kegan Paul Limited.

Mckeganey, N., & Barnard, M. (1996). Sex work on the streets: prostitutes and their clients. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Mikkonen, M., Kauppinen, J., Houvinen, M., & Aalto, E. (2007). Outreach work among marginalised populations in Europe. Guidelines on providing integrated outreach services. Amsterdam. Retrieved from http://www.correlationnet.org/doccenter/pdf_document_centre/book_outreach_fin.pdf National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2002). Principles of HIV prevention in drug-using populations. Retrieved from http://www.nhts.net/media/Principles of HIV Prevention (17).pdf Needle, R. H., Burrows, D., Friedman, S. R., Dorabjee, J., Touz, G., Badrieva, L., … Latkin, C. (2005). Effectiveness of community-based outreach in preventing HIV / AIDS among injecting drug users. International Journal of Drug Policy, 16, 45–57. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.02.009 Neri de Souza, F., Costa, A. P., & Moreira, A. (2011). Análise de dados qualitativos suportada pelo software webQDA.

In VII Conferência Internacional de TIC na Educação: Perspetivas de Inovação (CHALLANGES2011) (pp. 49–56).

Braga. Retrieved from https://www.webqda.com/flash_content/artigoChallanges2011.pdf Oliveira, A. (2011). Andar na vida. Prostituição de rua e reacção social. Coimbra: Almedina.

Parker, R., & Aggleton, P. (2003). HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 57(1), 13–24. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12753813 Pheterson, G. (1993). The whore stigma: female dishonor and male unworthiness. Social Text, (37), 39–64.

Piscitelli, A. (2005). Apresentação : gênero no mercado do sexo. Cadernos Pagu, (25), 7–23.

Pitcher, J. (2006). Support services for women working in the sex industry. In R. Campbell & M. O’Neill (Eds.), Sex work now (pp. 235–262). Cullompton: Willan.

Porter, J., & Bonilla, L. (2010). The ecology of street prostitution. In R. Weitzer (Ed.), Sex for sale. Prostitution, pornograhy, and the sex industry (2nd ed., pp. 163–185). New York and London: Routledge.

Rappaport, J. (1987). Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: toward a theory for community psychology.

American Journal of Community Psychology, 15(2), 121–48. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3604997 Rhodes, T. (1996). Outreach work with drug users: principles and practice. Strasbourg.

Riessman, C. K. (2000). Stigma and everyday resistance practices: childless women in south India. Gender & Society,

14(1), 111–135.

Roberts, N. (1996). A prostituição através dos tempos na sociedade ocidental. Lisboa: Editorial Presença.

Ross, M. W., Crisp, B. R., Mansson, S. A., & Hawkes, S. (2011). Occupational health and safety among commercial sex workers. Scand J Work Environ Health, 1–15. doi:10.5271/sjweh.3184 Rowlands, J. (1995). Empowerment examined. Development in Practice, 5(2), 101–107.

Sanders, T., O’Neill, M., & Pitcher, J. (2011). Prostitution. Sex work, policy & politics. London: SAGE Publications. Scambler, G. (1998). Stigma and disease: changing paradigms. The Lancet, 352, 1054–1055.

Scambler, G. (2004). Re-framing stigma: felt and enacted stigma and challenges to the sociology of chronic and disabling conditions. Social Theory & Health, (2), 29–46.

Scambler, G. (2007). Sex work stigma: Opportunist migrants in London. Sociology, 41(6), 1079–1096.

doi:10.1177/0038038507082316 Scott, J. W. (1995). Gênero: uma categoria útil de análise histórica. Educação & Realidade, 20(2), 71–99.

Spice, W. (2007). Management of sex workers and other high-risk groups. Occup Med (Lond), 57(5), 322–328.

doi:10.1093/occmed/kqm045 Spradley, J. P. (1979). The ethnographic interview. Belmont CA: Wadsworth Group/Thomson Learning.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (2007). Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing Grounded Theory (3rd ed.). London: SAGE Publications.

TAMPEP. (2012). Services4sexworkers: Directory of Health and Social Support Services for Sex Workers in Europe.

Retrieved from http://www.services4sexworkers.eu/s4swi/ UK Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP). (2008). Working with Sex Workers: Outreach. UK. Retrieved April 17, 2013, from http://www.uknswp.org/wp-content/uploads/GPG2.pdf Vala, J. (1986). A análise de conteúdo. In A. S. Silva & J. M. Pinto (Eds.), Metodologia das ciências sociais (pp. 101–128). Porto: Edições Afrontamento.

Van der Meulen, E. (2011). Action research with sex workers: Dismantling barriers and building bridges. Action Research, 9(4), 370–384. doi:10.1177/1476750311409767 Vanwesenbeeck, I. (2001). Another decade of social scientific work on sex work: A review of research 1990-2000. Annual Review of Sex Research, 12, 242–289.

Weiner, a. (1996). Understanding the social needs of streetwalking prostitutes. Social Work, 41(1), 97–105. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8560324 Weitzer, R. (2009). Sociology of Sex Work. Annual Review of Sociology, 35(1), 213–234. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120025 Weitzer, R. (2010). Sex work: paradigms and policies. In R. Weitzer (Ed.), Sex for sale. Prostitution, pornograhy, and the sex industry (2nd ed., pp. 1–43). New York: Routledge.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

14 May 2014

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-000-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

1

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-236

Subjects

Social psychology, collective psychology, cognitive psychology, psychotherapy

Cite this article as:

Graca*, M., & Goncalves, M. (2014). The Street-Based Sex Workers’ Contribution for a Socio-Educational Model of Intervention. In Z. Bekirogullari, & M. Y. Minas (Eds.), Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences – icCSBs 2014, vol 1. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 49-59). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2014.05.7