Voices of Personal Strengths and Recovery: A Qualitative Study on People with Serious Mental Illnesses

Abstract

Personal strengths are typically considered important for the development people’s abilities to deal with adversities in the general population. However, the personal strengths of people with serious mental illnesses have received little attention, even from healthcare providers whose primary focus was commonly on patients’ problems. Thus, opportunities to facilitate the recovery of people with serious mental illnesses using personal strengths were missed. This study aimed to explore and describe the types of personal strengths present in people with serious mental illnesses. In a qualitative study on a convenience sample of 102 community dwelling adults, the types and utilization of personal strengths towards mental health recovery were examined. Participants aged18 to 65 years old provided accounts on the use of their personal strengths through structured interviews. Major themes were derived through the interview transcripts using thematic analysis. A repertoire of personal strengths was described by people with serious mental illnesses including their compassion, creativity, acceptance of self and others, sense of humour and resilience. These strengths aided their recovery by helping them to focus on something positive. They trusted that they could recover and got involved in their own recovery. The results suggested that people with serious mental illnesses possessed personal strengths. Personal strengths could be a crucial factor to aid the recovery of people with serious mental illnesses. Findings could inform healthcare providers of the need to elicit and develop the personal strengths of people with serious mental illnesses to aid their recovery.

Keywords: community, mental health, recovery, mental illnesses, personal strengths

1. Background

Worldwide, hundreds of millions of people are affected by mental illnesses at any one time, creating an enormous tollon suffering and disability (WHO & WONCA, 2008). Even though mental illnesses did not kill people directly, mental illnesses accounted for about 25% of years of life lost due to both disability and premature mortality among the non-fatal diseases, (WHO, 2008). The World Health Organization’s (2008) report highlighted that 2.1% of males and 2.2% of females (6 437 million) in the world’s population had their deaths associated with mental illnesses.

The conventional wisdom in the mental health arena describes serious mental illnesses, as diseases with progressive deterioration. The dominance of the medical model persists where serious mental illnesses like schizophrenia are often considered chronic with irreversible neuropathological brain changes and information-processing deficits (Farkas, 2007). Psychiatry for all its well-meaning attempts has difficulties improving well-being for their patients, possibly due to the excessive focus on the negative aspects of mental disorders and the lack of attention given to positive approaches to enhance mental health (Cloninger, 2006). As a gloomy picture of schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses gets painted as chronic and irreversible, people with serious mental illnesses also view themselves in a negative light. They often realize that they are different from others, which in turn affects their self-esteem.

Interest in the recovery of people with mental health problems has been gaining attention in the psychiatric healthcare arena in recent times. For people with mental illnesses, the idea of recovery provides them with a sense of hope that they can continue to lead normal lives despite their illnesses (Oades, Deane, Crowe, Lambert & Lloyd, 2005). For both mental health practitioners and mental health providers, aiding the recovery of people with mental illnesses is a fundamental goal (Torrey, Wyzik, 2000 and Anthony, 1993). For policy makers and administrators, having spent so much money on mental health care, they would like to see that their efforts paid off; hence recovery becomes a measure of success for the different interventions and programs implemented. For example, the National Institute of Mental Health set promotion of recovery, not merely the reduction of symptoms, as their ultimate goal, while Anthony (1993) considered recovery from mental illnesses as the guiding vision for mental health service system. The shift towards recovery suggests a changing paradigm from one of negativity to positivity. This study is important as it looks beyond the symptoms and disabilities of people with mental illnesses to focus on their positive features such as strengths self-efficacy, resourcefulness and recovery. Only by addressing positive features can psychiatry be a science of well-being that focuses on reducing the stigma and disability that are known to be associated with mental disorders (Cloninger, 2006).

According to Saleeby (2002), every person possesses strengths that can be utilized to improve the quality of their life. Bundles of personal strengths have been identified by sociologists that contribute to desirable outcomes (Harris, McLaughlin, Brown, Becker, Dennis, 2000). Personal strengths are the positive traits that either create a sense of personal accomplishment, enhance people’s abilities to deal with adversities and/or promote personal development (adapted from Epstein & Rudolph, 2000, Peterson & Seligman, 2004 and Park, 2004). These strengths are typically considered important for the development people’s abilities to deal with adversities in the general population. Prior studies indicated

that non-biological factors like personal strengths contributed to positive mental health (Peterson, Park & Seligman, 2006, Epstein, 2000). These strengths could be contributing to the recovery of people with mental illnesses but were seldom examined as the focus tended to be on their problems. Thus, opportunities to facilitate the recovery of people with serious mental illnesses using personal strengths may have been missed.

2. Purpose

This study aimed to explore and describe the types of personal strengths present in people with serious mental illnesses.

3. Methods

3.1. Design

In a qualitative, explorative study, the types and utilization of personal strengths towards mental health recovery were examined. The qualitative component was as part of a mixed method study design so that words or narrative information generated from the study could complement the quantitative analysis (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004).

3.2 Setting

Participants were recruited from the community setting in Northeast Ohio. This study was set in the community rather than in the inpatient setting as hospitalized patients might be in the acute phase of their mental illnesses rather than the recovery phase, and the stability of their mental status might be questionable. This study involved the investigation of participants’ perception of their mental health recovery; hence the stability of their mental status was important.

3.3 Participants

102 participants were recruited using convenience sampling. Convenience sampling allowed researchers easy access to people with SMI. As people with SMI are a subset of the general population where the stigma associated with SMI may not allow them to come forward readily. As accessibility could be a concern, the sample was obtained by convenience sampling which is the most efficient way to access a hard-to-reach population (Lewis-Beck, Bryman & Liao, 2004).

Potential participants were identified by their responses to flyers posted in the community mental health agencies and outpatient clinics. They either contacted the principal investigator in person or by the contact information displayed on the flyers. The principal investigator met with the potential participant at a mutually agreed upon private venue in the community.

To be included in this study, participants met the following criteria:

those in hospital-based facilities (Killaspy, Rambarran & Bledin, 2008). Whether participants had been recently hospitalized or not were not taken into account as it was assumed that they had recovered sufficiently clinically to be out in the community. Furthermore, since this study assessed participants’ personal recovery in terms of growth and achievement and not symptomatic recovery, selecting the sample from the community kept the bias of psychological distress and psychotic symptoms from affecting participants’ personal recovery.

•Participants were also between 18 to 65 years old with a history of serious mental illnesses (SMI).

Serious Mental Illness in this study is defined as an individual who meets at least two of the three following criteria of

(a) diagnosis, (b) duration, and (C) disability described by the Administrative Code 5122-24-01(69) certification definitions of the Ohio Department of Mental Health.

•Participants had to be able to understand the nature and purpose of the study to provide informed consent. Their capacity to understand was assessed by giving them information regarding the study to read or after listening to the researcher read the information, to give an account of what the gist of the study was. Potential participants who were able to give an accurate overview of the study as determined by the researcher were eligible to participate in this study.

People with SMI who had abused substances (ie using drugs or substances that were notprescribed by the doctor or using drugs for recreation) since the last relapse of their mental illnesses till the point of encounter with the researcher were excluded from this study. The CAGEdapted toncluderugs instrument (CAGE-AID) was used to assess if participants had substance abuse since the last relapse of their mental illnesses. CAGE-AID is a four-item screening tool that is designed to identify drinking and drug problems via four constructsutdown,nnoyed,uilty andye-opener. The CAGE-AID exhibited a sensitively of 0.79 and a specificity of 0.77 for one or more positive responses. A positive screen was when there were one or more positive responses (Brown and Rounds, 1995). If potential participants answered yes to one or more of the questions posed while considering the time since the last relapse of their mental illnesses, they were not eligible to participate in the study.

3.4 Instruments

An interview guide was developed for this study containing questions to assess the types of personal strengths, the situations that participants utilized their personal strengths, and whether the use of these strengths relates to their mental health. These open-ended questions provided participants the opportunity to highlight their thoughts and feelings surrounding the topics that had been posed to them in the quantitative instruments without the constraints of having to limit their responses to the options given to them in the quantitative instruments. Since this study was preliminary research focusing on personal strengths and recovery, open-ended questions allowed further exploration of the topic and complemented the quantitative data collected from instruments. A sample question is: “How do you think your personal strengths relate to your mental health?”

3.5 Procedures

Ethical approval was sought from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) before commencement of the study. IRB

approved flyer/s were also mailed or emailed to these community mental health agencies. The study was promoted through face-to-face recruitment sessions, flyers placed at public locations and community mental health agencies as well as advertisements posted on social media sites such as Facebook. Potential participants approached the researchers directly or expressed their interest to participate through telephonic or electronic communication. The principal investigator screened the potential participants for their eligibility to participate in the study based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. If the potential participants were eligible and were interested to participate, they met with a researcher individually at a mutually agreed upon time and venue for informed consent taking and data collection. To maintain privacy for the participant, participants were encouraged to meet at places where they felt comfortable sharing about their mental health conditions. During the meeting, the researcher elicited participants’ responses based in a structured interview. To further increase the validity of the data, the researcher verified her understanding of participants’ response verbally before the responses were recorded, thus giving the participants an opportunity to correct any errors before records were finalized. This provided an opportunity for participants to recognize the responses to be true to them, hence increasing the credibility of the findings later on (Speziale & Carpenter, 2007). Field notes were taken as needed to record non-verbal responses from participants and if researchers felt that their presence had affected participants’ responses in anyway. For example, a participant may recognize that the researcher was a nurse that had provided care to the participant in the past and altered his/ her response accordingly. This is an example of reflexivity in qualitative research where researchers constantly examine their influence in the study (Speziale & Carpenter, 2007).

3.6Data analysis

All the recorded responses and field notes were transcribed for analysis. The analysis began by the principal investigator reading the entire transcript to get a sense of the data. Analysis of the data was done qualitatively using thematic analysis. In thematic analysis, researchers identify major themes that emerged from the data. Thematic analysis is more accessible to novice researcher as well as the explorative nature of this study as it is not dependent on a specialized theory unlike discourse analysis or grounded theory (Howitt & Cramer, 2007). Meaning units were identified by categorizing participants’ responses. Each meaning unit consisted of a string of text that depicted a coherent thought or idea. Meaning units that depicted similar ideas were then grouped together forming themes. Themes are abstract entities that emerge from the data. Themes capture and unify the meaning of the data (Polit & Beck, 2004).

Analysis of the transcript took place over a number of phases as in the process of thematic analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). In phase 1, the entire transcript was read through to gain an overview of participants’ responses. This was followed by phase 2 where categories or codes were generated for meaning units of data that represented a certain idea. The transcript was re-arranged such that extracts of participants’ responses representing each category were placed together. The number of extracts and the number of participants who provided the extracts were noted. In the third phase, the categories were reviewed to derive at potential themes. Themes are the broader, over-arching construct that represent units of data. Six potential themes namely, 1) use of personal strengths to understand other people, 2) use of compassion to help other people, 3) use of personal strengths to work, 4) use of personal strengths for personal growth, 5) use of personal strengths for individual development, 6) use of personal strengths for mental health were derived. The data was collated within the potential themes identified. The transcript was again re-arranged such that extracts representing similar themes were placed together. In phase 4, these potential themes were further refined. Every category of extracts that fell under each potential theme was reviewed again to determine if the theme was represented in the data. Potential themes with too little data to support the themes were combined and renamed.

The process of analysis might also be repeated and themes revised so that the themes could accurately reflect the meaning of the data in the end. The principal investigator then re-reads the transcript with the themes in mind to ensure accuracy.

4. Results

4.1 Participants’ characteristics

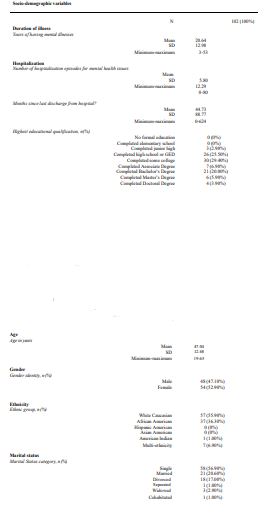

102 people with histories of serious mental illnesses participated in the study. An overview of the socio-demographic characteristics was presented in table 1. About half of the participants were females (54 of 102, 52.90%) and the other half males (48 of 102, 47.10%). Among the males, two were in the process of transferring their gender. Their ages ranged from 19 to 65 with the average age being 47.04 years.

4.2 Types and Utilization of Personal Strengths

Personal Strengths Types and Utilization Qualitative analysis of the results of this current study revealed that participants had the following personal strengths:

- Able to understand others

- Compassion towards others

- Creativity to do work

- Organization skills and work

- Resourcefulness and advocacy

- Acceptance and love for oneself

- Sense of humour to feel at ease

- Resilience and personal growth.

- Resilience and personal growth.

These personal strengths assisted them in the development of relationships with people and to fulfil the work that they do.

4.2.1 Use of personal strengths in relationships with people.

A major theme identified was that participants used their personal strengths in their relationships with people.

Many participants generally considered themselves as being more understanding towardsother people. They had experiences with serious mental illnesses that affected various aspects of their lives and could relate to other people who were facing difficulties in their lives even if these difficulties were not related to mental illnesses. From their experiences with mental illnesses, participants understood that many things were sometimes beyond the control of an individual. They developed a deeper understanding of people’s situations and learned not to be judgmental about other people’s situations.

As one participant put it

The theme of compassion also surfaced most frequently in this research study.

Participants were able to transcend their understanding of other people’s situations into compassion for others and were sometimes even able to help other people despite their own limitations. They understood the difficulties that people might have.

Firstly, participants used their sense of understanding andcompassion to help other people. Many participants translated their understanding and compassion towards other people into actions. They reached out and connected with people, just as one participant had said “I can discuss things clearly with people who have issues going on in their lives. I can share my experiences clearly”.

A good proportion of the participants, about half of them, joined a national organization to be connected with other people with mental health issues. Having experienced mental health issues themselves, they could truly understand the struggles of dealing with mental health issues. Their understanding and compassion helped them break down barriers so that they could communicate better with other people

Secondly, while participants’ understanding and compassionate helped them to help others, theythemselves were helped too. Sometimes, their understanding and compassion towards other people were translated inwards onto themselves. It helped them to understand their own issues.

Personal strengths were also used to help participants do the work they do.

At least 13 participants perceived being creative as one of their personal strengths that helped

them in the work they do.

One participant referred to re-arranging the toolbox to shorten the time it took for him to assemble mechanical parts for his work and surprised his colleague with his quick timing. Another spoke about re-purposing other items to help him/ her perform tasks. For example, a participant used shopping cart, computer cart, and chairs with wheels to move furniture from one location to another when he could not get transportation.

Another participant spoke about employing her creativity skills to gain employment. She responded to a job advertisement while posing as an ex-employer of the job applicant, claiming to help an ex-employee get a job as the exemployee had been a great worker. After writing recommendation letters for herself sent in the capacity of an exemployer, the participant landed herself a job. The new company was convinced about the caliber of the applicant after learning that an ex-employer would still care about an ex-employee.

Creativity was also being employed by participants in their interaction with other people in their jobs. A participant who did speaking assignments actually incorporated stories, acting and performance when presenting about mental illness to her audience. These were also incorporated by a participant who teaches other children for a living.

The use of creativity brought along several benefits. In addition to using creativity to overcome obstacles,

participants also found that employing creativity kept people at ease and they could communicate their thoughts to their

co-workers better and do their work easier.

A number of participants claimed to prefer structure in their lives. They believed thatbeing organized was one of their personal strengths that helped them in their work. There were participants who made a “to-do list”, remove duplicate files, or acted like “detectives” to find out problems step by step and resolved issues systematically.

Participants also seemed to perceive themselves as being resourceful despite havingmental health issues. In turn, their resourcefulness capabilities had helped them gained resources for themselves and they were happy to use these resources in advocating for people with mental health issues.

Many participants have been through difficult times and gotten around to recovery. In the process, they learned about different resources that could be tapped upon and shared these resources with other people with mental health issues.

Participants spoke about resources, knowing where to get them for transportation to places they need to go or using food stamps as a way to off-set some of the rent for their lodging. A participant spoke about how she had helped 4 or 5 people prevented their homes from being foreclosed when the economy was bad. She advocated for these people and helped them to work out loan repayment plans with banks instead of having their homes foreclosed.

They were also able to tap into resources to help other people’s mental health. For example, a participant mentioned about how she sought out other programs in other community groups and recommended them to people attending her peer support group when funding to the community agency that she usually went to was cut.

“Advocating is what I have done for years and my therapist has been surprised or amazed at my capabilities. I seem to know more resources than they do and I love sharing”Participants’ advocacy was also evident in the quantitative data where 78.5% of the participants either agreed or strongly agreed to the item in mental health recovery measure (MHRM), I advocate for the rights of myself and others with mental health problems.”

4.2.2 Use of personal strengths in relationships with oneself.

Self-acceptance was another personal strength that emerged from this researchinterview. Most participants acknowledged the presence of stigma surrounding mental illnesses and found it hard to accept themselves for having mental illnesses initially. However, over time, they learned to accept themselves for having mental illnesses and not allow themselves to be defined by their illnesses.

To at least three participants, having mental illness was just part of life. Participants accepted who they are, what life

is, and what they can or cannot do.

As participants become more accepting of themselves, acknowledging who they are and not be too overly concerned

about what they can or cannot do, they also found themselves feeling a deeper love for themselves.

Sense of humor was also a common personal strength that participants perceivedthemselves as having. Sense of humor appeared to help participants feel more at ease with themselves through down times or when in awkward situations such as in a crowd.

One particular participant referred to his sense of humor as a mask that helped him get away from people when in a crowd to get in touch with himself.

I am in a crowd my humour pops out… it's a mask for me to hide behind for me to be with myself … it feels good”

Many participants felt that experiencing and going through mental illnesses hadmade them resilient to adversities in their life. According to participants, the nature of mental illnesses is one that involves a person getting better someday and becoming worse another. It is never stagnant and going through such uncertain times helps participants become more resilient to their lives.

“I persevere as I dealt with anxiety, depression and agoraphobia. I refuse to let my illness interfere with my career” “I am strong, I do not let mental illness to beat me”

Some people developed their resilience by persevering and fighting through mental illnesses, while others learn to let

go of their setbacks and become stronger in the process.

“I am a fighter”“I have a will to just keep going on”“While I am easily embarrassed and ashamed, I let go of me, I do not let my mental illness stop me from doing anything”.

Participants’ learned not to be defeated by their mental illnesses, but valued the fact that they had managed to stay resilient through setbacks.

“At one point in my treatment, I had an intake person who told me I would never work again but now I am resilient. “going through these uncertain setbacks I feel the word resilience comes to mind as a strength and I believe I have been given a lot of opportunities to learn about life after being diagnosed.”

Through their experiences with mental illnesses, and overcoming mental illnesses without being defeated, they

felt that they have gained a set of skills to deal with setbacks.

“My resilience has helped me accept the opportunities that helped me grow”“We have to START with our we have and grow on that…start with my strengths and utilize them to grow”

Many participants mentioned that they depend on their family for support. Family membersprovided the listening ear for participants to share their struggles and the help in times of need. Family members were the first line of people that participants could speak to.

“when I first got my mental illness. I talk to my family almost everyday”After speaking to family, participants claimed to generally feel a sense of comfort and it feels good for them to know that they are still supported and cared for even when they have mental illnesses.

4.3 Utilization of Personal Strengths for mental health

The themes relating to this question were derived primarily from analysing participants’ response to open-

Participants basically found that their personal strengths helped them in their mental health recovery in a number of ways:

- Cope with mental illnesses.

- Focus on something positive.

- To not give up

- To get involve

- Provide time to recover.

- Have faith in recovery

Mental illness could be “tormenting” at times, but participants felt that their personalstrengths helped them cope with mental illnesses. Personal strengths, to many participants, were also positive attributes that kept them hopeful about life with mental illnesses.

Personal strengths could be to be a catalyst that adjusted their emotions to distract them from the difficulties of

dealing with mental health issues while keeping them happy.

Personal strengths also helped to keep them motivated to continue to work towards their recovery. One participant spoke about his personal strength of having a keen curiosity to drive him to learn about how to deal with mental health issues.

An excerpt from a participant below summarized the interplay between mental illnesses and personal strengths. Personal strengths become something that participants can fall back on. When the struggles of mental illness become too much to bear, personal strengths pulled them up and pushed them to work on their recovery.

Many participants also reported that thinking about personal strengths helped themmaintain a positive mindset and this was helpful to their recovery. Positive mindset helped them believed that they could overcome their mental health issues. They can remain hopeful about the future even if they are struggling with mental illnesses now. Working on something positive such as building up their personal strengths instead of focusing on their difficulties with mental health issues provided them with a positive outlook of the future.

An excerpt from a participant below summarized how participants focus on something positive like their

personal strengths helped them recover.

At least 4 participants spoke about them being able to be in recovery because they have not given up

on themselves. They kept going and pushed on through their struggles to propel them towards recovery.

Participants understood that dealing with mental health issues was a constant struggle. However, the “never give up” attitude of participants kept them committed to recovery. They continued to do what they perceived as necessary for recovery. For example, they followed through with medical appointments even if they were frustrated and had not reaped the benefits of medical care initially. Participants claimed that their perseverance almost always helped them to recover over time.

The excerpt from a participant below summarizes how participants’ never give up attitude helped them

through recovery.

Participants’ ability to remain calm under difficult circumstances also surfaced as apersonal

strength that provided participants time for recovery to take place. As some participants reflected on the time when they were first diagnosed with mental illness, they wished they had not panicked. When participants remained calm, they found that they did not get overwhelmed or flustered; hence helping them remained focused to do what it takes to recover.

The following excerpts summarized the relation between remaining calm and having the time to recover.

Participants perceived being involved in their mental health as a way to help them in their recovery.About half of the participants were involved in a national mental health consumer agency. To a number of participants, the key to recovery was not being afraid to reach out for help. They sought help from psychiatrists, nurses, therapists, counsellors when needed and participated in medical appointments, therapy and counselling sessions.

Some participants also stated their personal strength of being willing to learn as being helpful in their recovery. They got themselves involved in their mental health by getting educated about mental health. In the process, they felt empowered to take on a greater role in their recovery.

A number of participants became peer support specialists, leaders of support groups or volunteers at mental health agencies offering support to other people with mental health issues. By doing this, they kept their focus beyond their own mental health issues.

Faith or spirituality emerged frequently as personal strengths that helped participants throughbad times to overcome their mental health issues, or difficult times at work or with their family members. Faith seemed to provide a more positive outlook on their life and motivate them to want to get better and work through the difficult times.

Participants having the faith that they will eventually recover have also helped them take risks to move forward with

their recovery.

“Having faith have helped me take the chances I have taken to move along with my recovery … Things kinda got better from there”

To sum up, participants’ personal strengths and mentalhealth recovery were closely intertwined. As participants experience progress in their recovery from mental illnesses, they also built up their personal strengths.

“my strengths have come out of recovery. My strengths could develop my recovery further, but I think my strengths have emerged from my recovery”

However, even if they were to have a relapse of their mental illnesses, participants may still be moving forward

with their recovery as the repertoire of their personal strengths continue to progress.

“with every relapse, I am becoming more stable, who I am where I am and become more refine so my strengths can shine”

5. Discussion

While it is important to recognize the impact of psychopathology on people with mental illnesses, this study offered an unique opportunity for to understand participants’ personal strengths. In the promotion of well-being in mental health services, emphasis on the person’s strengths is needed (Slade, 2010). In line with the new positive paradigm, mental health recovery should emphasize the personal journey of growth and achievement rather than the alleviation of mental illness symptoms (McGrath & Jarret, 2004, Slade, 2010).

Individuals despite having serious mental illnesses still possessed a repertoire of personal strengths. Personal strengths remained even when one had been diagnosed with mental illnesses (Deegan, 2005). People with psychiatric disorders instead of taking pharmacological products, have used activities that they perceived as meaningful, termed as personal medicine by the author, to aid their recovery (Deegan, 2005).

The study uncovered that understanding, compassion, creativity, resourcefulness and advocacy, organizational skills and humour were some examples of personal strengths being utilized by participants in their relationships with people, in their work and for their individual self. Similarly, a large scale web-based retrospective study conducted previously on a sample size of 2,087 participants found that recovery from psychological disorders was associated with greater personal character strengths (Peterson, Park & Seligman, 2006). In this study, participants also revealed that focusing on building up of personal strengths for people with serious mental illnesses instead of their mental health difficulties helped them remain positive in times of adversity and aided their recovery. Personal strengths helped participants coped with their mental illnesses, focused on positive things, not gave up on themselves and helped got them involved in their mental health. These aided participants’ progress towards recovery. In addition, personal strengths also provided participants the faith to believe that they could recover and provided time for recovery to take place.

In addition, this study was directed at the better understanding of the personal strengths of people with mental

illnesses that drove them towards recovery. Clinicians are in the position to identify and work with people with mental

illnesses on their personal strengths. Some capacities, resources, and assets commonly appear on a roster of strengths. These include: personal qualities, virtues and traits; what the person has learned about him/herself, others and the world; what people know about the world around them from education or life experience; the talents people have; cultural and personal stories, informal networks, institutions or professional entities etc (Epstein, Ruldolph & Epstein, 2000; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Saleebey (2006) suggested that personal strengths were found by looking for evidence of the person’s interests, talents and competencies and by listening to their stories. Epstein et al (2004) suggested chatting informally with mental health service users to help elicit their strengths. With these different strategies, clinicians could elicit personal strengths from people with mental illnesses or help them identify their personal strengths. The findings expanded our knowledge about recovery from mental illnesses by focusing on personal strengths and positive concepts such as strengths self-efficacy, resourcefulness and mental health recovery. In the past, serious mental illnesses were viewed pessimistically, with the course of illness being deteriorative and treatment being stabilization of the illness condition at best even if outcomes were not all bad (Anthony, 1993, Farkas, 2007). Findings from this current study could aid in propelling the field of psychiatry away from deficit preoccupation to positive qualities of individuals with mental health issue such as strengths self-efficacy and resourcefulness. Such findings could be important for the integration of strategies promoting personal strengths and resourcefulness capabilities to promote recovery and inform the future development of frameworks and interventions that focus on the personal strengths of people with mental illnesses.

6. Conclusions

The personal strengths of human beings can be illuminated in adversities. After years of studying human

weaknesses and psychological pathology, this study attempted a scientific pursuit of human strengths that brought about

positive outcome in adversities. The results suggested that people with serious mental illnesses possessed personal strengths. Personal strengths could be a crucial factor to aid the recovery of people with serious mental illnesses. Findings could inform healthcare providers of the need to elicit and develop the personal strengths of people with serious mental illnesses to aid their recovery.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledgement the assistance provided by Dr Jaclene Zauszniewski, Dr Cheryl Killion as well as other faculty at Case Western Reserve University School of Nursing, the nurses and staff at Department of Nursing Training and Department of Nursing Administration at the Institute of Mental Health, Singapore and all participants of this study without whom this study would not have been possible.

References

Anthony, W. (1993). Recovery from mental illnesses: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial RehabilitationJournal, 16(4), 11-23.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 (2), 77-101.

Brown, R. L., Rounds, L. A. (1995). Conjoint screening questionnaires for alcohol and other drug abuse: Criterion validity in a primary care practice. Wisconsin Medical Journal, 94(3), 135-40. European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences eISSN: 2357-1330 20-39

Cloninger, C. R. (2006). The science of well-being: An integrated approach to mental health and its disorders. World Psychiatry, 5(2), 71-76.

Deegan, P. (1996). Recovery as a journey of the heart. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 19, 91–97

Epstein, M. H., Ruldolph, S., & Epstein, A. A. (2000). Strength based assessment. Teaching Exceptional Children, 32(6), 50-54.

Farkas, M. (2007). The vision of recovery today: What it is and what it means for services. World Psychiatry, 6, 68-74.

Harris, C. C., McLaughlin, W., Brown, G., Becker, Dennis R. (2000). Rural communities in the Inland Northwest: An assessment of small ruralcommunities in the interior and Upper Columbia River Basins General Technical Report PNW-GTR-477 ). Retrieved from US department ofAgriculture Forest Service website: http://www.fs.fed.us/pnw/pubs/gtr477.pdf

Howitt, D., & Cramer, D. (2007). Introduction to research methods in Psychology, London: Prentice-Hall.

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 603-619.

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Greater strengths of character and recovery from illness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(1), 17-26.

Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2004). Nursing research: Principles and methods(7th ed.). Philadelphia:Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Oades, L., Deane, F., Crowe, T., Lambert, W. G., Kavanagh, D., & Lloyd, C. (2005). Collaborative recovery: an integrative model for working with individuals who experience chronic and recurring mental illness. Australasian Psychiatry, 13(3), 279-284. Killaspy, H., Rambarran, D., & Bledin, K. (2008). Mental health needs of clients of rehabilitation services: A survey in one Trust. Journal of MentalHealth, 17(2), 207-218. DOI: 10.1080/09638230701506275.

Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose Time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(14), 14-26.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., Bryman, A., Liao, T. F. (2004). SAGE Encyclopaedia of social science research methods. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications.

McGrath, P., & Jarrett, V. (2004). A slab over my head: Recovery insights from a consumer's perspective. The International Journal of PsychosocialRehabilitation, 9(1), 61-78.

Slade, M. (2010). Mental illness and well-being: the central importance of positive psychology and recovery approaches. Health Services Research, 10, 26, 1-14. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/10/26

Speziale, H. S., & Carpenter, D. R. (2007). Qualitative research in Nursing. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Torrey, W. C., & Wyzik, P. (2000). The recovery vision as a service improvement guide for community mental health centers providers. CommunityMental Health Journal, 36(2), 209-216.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2008). The global burden of disease 2004 update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization (WHO) & World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA) (2008). Integrating mental health into primary care: A globalperspective. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, WONCA.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

14 May 2014

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-000-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

1

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-236

Subjects

Social psychology, collective psychology, cognitive psychology, psychotherapy

Cite this article as:

Xie, H. (2014). Voices of Personal Strengths and Recovery: A Qualitative Study on People with Serious Mental Illnesses. In Z. Bekirogullari, & M. Y. Minas (Eds.), Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences – icCSBs 2014, vol 1. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 20-39). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2014.05.4